The Demon, as presented in art, has become a theme often employed to represent a madness that has developed within the artist. This demon can serve as both a muse and a destructive force for the artist who cannot find a means to control it. Mikhail Vrubel looked to the Demon throughout his life; adapting him to his constantly changing world. The evolution of Vrubel’s Demon is what will be examined here using the theories of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. The development of Vrubel’s Demon is best seen in two works that almost bookend his career: Demon Seated of 1890 and Demon Downcast of 1902.

Composition and Meaning in Demon Seated and Demon Downcast

Demon Seated (Fig. 1) depicts the figure of the Demon sitting atop a mountain. There is tension in his muscles and interlocked fingers which sharply contrasts with the slumped over body and melancholy expression of his face. He appears passive and introverted yet proud, solitary, and sensitive. He is the antithesis of the feminine, yet possesses feminine attributes in the long hair, soft face, and pouty mouth. His eyes are filled with a longing for love in a cold and alienated world. Vrubel described this Demon as “a spirit uniting in itself masculine and feminine qualities…a spirit, not so much evil as suffering and sorrowing, but in all that a powerful spirit…a majestic spirit”. [1] In his androgyny, the Demon is a perfect fusion of the soul’s earthly and heavenly elements.[2] The evening setting amidst an ethereal landscape that is distant and disengaged assists in the feelings of sadness and solitude.[3] There is the sense of an uneasy equilibrium between the wistful landscape and the forlorn expression that suggests places and events are but a haze to the immortal soul that is condemned.[4]

Demon Seated is the generalized depiction of the soul. The inner focus of the eyes, the intensity of the huddled movement of the body, and the clasped hands all isolate the figure and produce an image of profound introspection. The enlarged flowers fill the whole area to the right and force their way to the foreground. They are visually pitted against the area to the left of the Demon, towards which its face is turned: a void. The planes are complex and not uniform, alternating in shape and direction, creating tensions. The colors suggest movement as they move down to more open, faceted, crystalline forms. The sunset has a menacing glow, suggestive of the fires of hell. The irregularity and abrupt juxtaposition of shapes suggest the technique of mosaics. The elusive spatial balance is enclosed within a shallow space, which may be called proto-Cubist because the boundaries are ambiguous and the volumes contrast and expand, appear and disappear, setting up rhythms. The circular movement, ambiguities, emptiness on the left versus the press of form on the right could act as metaphors for the claustrophobic state of mind of the Demon.[5]

The Demon in Demon Downcast (Fig. 2) is altogether a different being. The calmness and reserve that is present in Demon Seated has dramatically altered. There is a prevailing sense of catastrophe in the strange mountainous landscape. He is thrown among jagged mountains, peacock-feathered wings outspread, body twisted and broken; he is crushed both physically and psychologically. Yet, his lips are firmly compressed, nostrils flared, and his eyes stare rigidly ahead, the melancholy replaced by scorn. The juxtaposition of the blue and purple with tan and black gives the scene a subdued yet ominous atmosphere, suggesting a struggle between light and dark, and beauty in death.[6] What is most disconcerting about the image is the contrast of this chaotic fall from grace with the disturbing, windless landscape.

There is a new intensity of despair felt by the Demon in his failure to forge new human bonds and transcend his lack of faith of love. The Demon’s appearance in Demon Downcast is strikingly different from the Demon seen in Demon Seated. There are wings on this demon which have given way to agitated peacock-like feathers; the right arm is folded over his head in a companion gesture to the left arm, expressing a more concentrated tension and grief which mingle with the face which holds an expression of mistrust, horror, and sadness. Ekaterina Gay, Vrubel’s sister-in-law, wrote of Demon Downcast: “There were days when the Demon was very awe-inspiring, then it would take on a facial expression of deep sorrow and a new kind of beauty.”[7]

Vrubel’s Demons

To understand these demons, one must know how the subject came to be such a fascination to Vrubel. Vrubel’s first major commissions as an artist were for the restorations of St. Kirill’s in Kiev. His participation here would lead to the development of a Byzantine style that would be seen in all of his subsequent work. During his stay in Kiev, Vrubel developed a tendency to drink too much, throw away money, and participated in numerous amorous escapades which led him to disappear without warning. This lack of self-discipline and loose manner of living created unusual patterns of thought and temperament bringing about extravagant behavior. Because of this behavior he committed numerous offenses against societal conventions and had lapses with reality, such as a belief in his father’s death, and a growing frequency of migraines. Despite this, his work never showed signs of it. Also, while in Kiev, he began a lifelong fascination with creating images akin to classic Russian folktales. More importantly, however, Kiev was the place in which Vrubel saw Anton Rubenstein’s opera The Demon for the first time, giving him his initial inspiration for the subject that would be a constant throughout his artistic career.

As Vrubel began focusing more and more on his art, he decided that he needed to make his own discoveries and find a subject of fundamental scope, eventually turning to Mikhail Lermontov’s epic poem The Demon in 1885. By mid-1885 he had begun his first depiction of the Demon, based on Lermontov’s poem. This first image was destroyed by Vrubel but its influence on later incarnations of the Demon is apparent in its depth of idea and expression.

In May of 1890, Vrubel had begun a new version of the Demon, describing him as “a half-nude, winged, youthful, dejectedly thoughtful figure who seats, hugging his knees, against the background of a sunset and contemplates a flowering meadow from which small branches weighed down by flowers are straining toward it.”[8] This is the Demon he came to believe would make him famous; this would be the Demon of Demon Seated.

Literary Illustrations of The Demon

Vrubel had many sources of inspiration from which he drew his first ideas concerning the Demon but it was within the realm of literature that Vrubel found what he was seeking. With a deep interest in the literary and philosophical classics, Vrubel found demons in the work of Nikolai Gogol and Aleksandr Pushkin.[9] But above all, Vrubel associated the figure of the Demon with some romantic, transcendental world of love and death, and nothing exemplified this ideal better than Mikhail Lermontov’s epic poem The Demon, first published in 1842.

In 1891, several special jubilee editions of Lermontov’s poems were to be published in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the poet’s death. Vrubel had been approached to provide illustrations for the I. N. Kushnerev edition. For The Demon, he provided twenty-two illustrations done in watercolor and gouache; eleven of them were published.[10] Art critic Vladimir Stasov wrote of Vrubel’s illustrations for Lermontov’s poem: “Vrubel in his Demons has given us the most awful examples of revolting and repulsive decadence.”[11] Although many did not like Vrubel’s illustrations, the special edition is now remembered and celebrated for his artistic contribution. The Demon of Lermontov’s creation was on a quest to “incarnate the spirit of exile,” and this, more than anything else, aided in the development and viewpoint of Vrubel’s Demon.

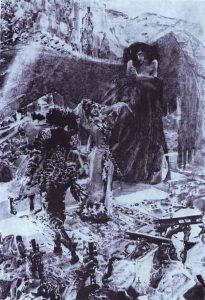

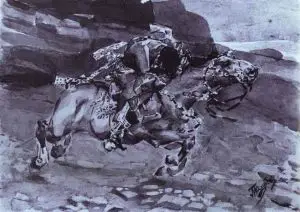

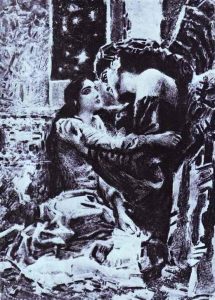

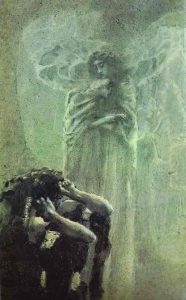

The poem opens with the Demon, a fallen angel, flying amongst the clouds. As he is flying, he sees below the beautiful princess, Tamara, with whom he falls in love (Fig. 3). In an attempt to avoid his lonely fate, he decides to seduce her, but discovers that she is engaged. The Demon is soon torn between his love for Tamara and his own destructive nature. Following his heart, he desperately and deliberately wishes death upon her fiancé (Fig. 4). In mourning, Tamara begins a new life in a convent, where the Demon follows her. At last giving in to his love, they embrace, and she perishes in his arms (Fig. 5). The Demon tearfully watches as an angel carries Tamara’s soul to heaven. In the end, the Demon is left in the lonely, desolate state in which he began (Fig. 6).[12]

He was originally a pure creature, a “happy firstling of creation,” who is now burdened by eternal flight until he sees Tamara dancing. The scene is festive, in celebration of her pending marriage. The Demon sees her and is moved, “his memory traced the joys that he had known above.” He becomes jealous of the groom and selfishly kills him. He pursues Tamara until she finally gives in. Because of this selfishness, Tamara dies. But even in her death, the Demon refuses to admit his role in her demise, choosing, instead, to continue to revolt against the world. Lermontov’s creature represents for the first time, the concept of a Demon as an ordinary human with its selfish passions, uncontrolled appetite, cowardly refusals, and cold absorption in itself.[13] It is this Demon in whom Vrubel found what he had been longing to depict.

Vrubel’s Demon, however, should be seen as more of a visual, rather than a literal, interpretation of Lermontov’s. Lermontov’s Demon is haughty, arrogant, and proud; his love for Tamara is more of an obsession to possess someone rather than to love someone. Vrubel’s Demon, as seen in Demon Seated, is infused with a symbolism that is “replete with thought and always obscure in its depth” becoming almost godlike, in his final moments, as seen in Demon Downcast.[14] In fact, neither Demon Seated nor Demon Downcast illustrates any passage in Lermontov’s narrative. If literary inspiration is to be seen in Demon Seated it is found in an earlier Lermontov poem of 1829, entitled “My Demon”:

Among the fallen leaves stands his immovable throne.

There, among still winds, he sits dejected and somber.[15]

In this a literary interpretation can be perceived with the “immovable” aspect singled out by Vrubel for expression. You can sense the emptiness and misery felt by the Demon. His body proportions seem out of place with the enclosed landscape around him. His figure seems to be overrunning the boundaries of the canvas, invading the viewer’s space. Yet, through the act of the childlike gesture of holding his knees and looking away from the viewer into the distance, he is psychologically self-contained. The mosaic-like quality of the landscape depiction provides an almost circular movement throughout the canvas from the pressing forms of the flowers on the right to the menacing glow of the sunset on the left. Tears have formed in his eye with one rolling down his cheek. All of this is utilized to convey the Demon’s humanity and his striving to go beyond the limitations of the commonplace.[16] This was the demon that Vrubel saw as misunderstood. Here is a figure, not of darkness, but of light; a benevolent, otherworldly figure who has been cast out from heaven.

As with Demon Seated, Demon Downcast has literary counterpart in Lermontov. According to Aline Isdebsky-Pritchard, Vrubel’s Demon in this work is found in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, a source used by Lermontov for his Demon. Milton’s Satan is described as:

…cast out from Heaven…

…Hurled headlong flaming from the ethereal sky…

…He lay vanquished, rolling in the fiery gulf,

Confounded but immortal. But his doom

Reserved him to more wrath; for now the thought

Both of lost happiness and lasting pain

Torments him: round he throws his baleful eyes,

That witnessed huge affliction and dismay,

Mixed with obdurate pride and steadfast hate.[17]

Milton’s imagery seems directly projected onto Vrubel’s canvas. His fate is to struggle within his own spirit, remaining locked within its own battleground. He is hideous, misshapen, and as rigid as stone. He has fallen from a great height, and one can sense and see the power of his collision with the landscape. But his head remains upright, wearing a thorny crown that alludes to Christ’s sufferings, and an expression of deep existential anxiety which still contains great pride and determination.

Lermontov’s Demon contained romantically heroic dimensions centering on ideas and emotions having to do with the individual’s capacity for good and evil. His demon was irrational and complex, whose encounter with the Angel only intensifies his destructive urge. Vrubel explained his own vision of the Demon as “generally misunderstood. The demon is confused with the devil and evil spirits…But “the demon” means “the soul,” and it incarnates the eternal struggle of the mutinous human spirit seeking reconciliation of its stormy passions with a knowledge of life, it finds no answer to its doubts either on earth or in heaven.”[18]

The Demon embodies Vrubel’s concept of the soul’s essence as active and disruptive in the “eternal struggle of the mutinous human spirit.” and in creative conflict with the world. The Demon is subjected to passion and torment; he is the victim of events and of his response to them. If the figure of the Demon seems unexpectedly peaceful, it is only in contrast to the inner torments of Lermontov’s hero and to all of Vrubel’s subsequent works on the subject. This relative repose is expressed in the position of the Demon, almost geometric in its stability: a broad-based conical mass, culminating in the top of the head, slowly rises across the center of the canvas, and closes the arms and shoulders within a diamond shape. The body itself is composed of smaller geometric units, whose facets do not represent actual muscular structure, but are, rather their visual equivalents. The substances are neither cloth nor flesh; they are sculptural in essence. Details of the shoulder convey the way in which the body is actually constructed of a mass of independent sculptural units. These units have the consistency of some dark, hard material, and the colors are indefinite tans and greys. The scale of the painting makes this method very evident. Sudden jumps in color value build up the planes which are the units forming open volumes. They seem to prefigure early Cubism, and the total figure has the structural underlying solidity of that style.

The face of the Demon, shown in profile, is pensively sad rather than despairing. Its visible eye is filled with tears, while a large tear rolls down along the nose. Lermontov uses tears in the poem to express the Demon’s momentary freedom from his usual state of alienation and it serves a similar function for Vrubel. It is a measure of the Demon’s humanity. Tears also connote the experience of suffering, which Vrubel welcomed as an integral aspect of life. Beyond representing Lermontov’s solitary outcast and the struggle of the sentient individual soul between good and evil impulses, the Demon is also a concrete force of nature, with its roots in the material universe.

Vrubel’s Demons in an Era of Ideas

Far from just literary inspiration, Vrubel lived in an era that was rapidly changing. The last decades of the nineteenth century in Russian life and culture were a volatile mix of great expectations and ominous visions. This era produced great and everlasting works of art, poetry, and music that became known as the Russian Silver Age.

The Russian Silver Age, with its connotations of art, dusk, and the reflected brilliance of the moon and stars, is normally applied to the last 25 years of Tsarist culture, 1892-1917.[19] During the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, faith faded and the bearing of another’s burdens sapped initiative and self-sufficiency. Deeply disoriented, people began to grope for short-cuts to lost certainties and for the vulnerable and psychologically unstable, there was the possibility of experimenting with drugs, alcohol, and sexual perversion.[20] Artists of the era wanted to show the isolation of the individual in a world of unique feeling. The Russian Symbolist movement sought to connect “the abyss which lies between man and nature in the contemporary world.”[21] Symbolism is the culmination of these historical processes which have their origin in the cult of beauty through pessimism. The artist’s journey within the self to find stability was sought in an idealization of the past.

This road was to lead back to a new acceptance of the moral imperative: whether as tragic courage, existential choice, or acceptance of the implications of the cross of Christ.[22] But, as the rigid institutions of tsarist Russia were eroding, a new-found freedom began to flourish and a tide of modern art and ideas swept across the country, bridging the void between the exotic past and the modern world which aided in informing and enriching Russia’s modernism, distinguishing it from its counterparts. It acknowledged the new art and science of the West but modified them to local custom so as to produce an eclectic mix of traditions. Thus, Russian Symbolism developed out of several ideas such as the denial of the world of appearances, the search for a more pristine artistic form, the transcending of established social and moral codes, and the emphasis on the inner world.[23]

The Symbolists made every effort to escape the present by looking back to an Arcadian landscape of pristine myth and fable or forward to a utopian synthesis of art, religion, and organic life. It represented an entire world view and a way of life which engendered intense dreams, religious explorations, decorative rhetoric, and various kinds of metaphysical creativity. The Symbolists emphasis on the private experiences and on the work of art as a reflection of the inner world was allied with their desire to produce works that were aesthetically unique as well as containing elements of national character. The quest for a national identity informed their philosophy with an emphasis on the study of nature and the revival of styles from the Middles Ages and Russian Orthodoxy as sources for inspiration. Because of this turn in style and inspiration, Russian Symbolists aspired to transcend the impersonal conventions of sociopolitical reality and of false, mimetic reproduction, so as to reach the spiritual plane of existence.[24] Vrubel’s images of prophets, saints, and demons all express the nervous tension and feverish energy of the Russian Silver Age.[25]

Out of this struggle, several artistic circles formed, each having their own agenda and their own way of putting into expression the world they saw disintegrating in front of them. One such group was the Symbolist members of Mir iskusstva, or the World of Art group. This group of artists sought to leave the social and political alienation of reality for a more subjective, individual, and expressive form of personal feelings and thoughts which were more in tune with Symbolist doctrine.

Founded by industrialist and entrepreneur, Savva Mamontov, the World of Art circle put their attention to artistic craft, the cult of retrospective beauty, and assumed distance from the ills of sociopolitical reality. World of Art’s primary hope was to create a new artistic code through the recognition and rediscovery of bygone cultures.[26]

To the members of Mir iskusstva, a work of art is important not in itself, but as an expression of the personality of the artist. They were more interested in the creative personality than in the end product. They wanted art to be absolutely free of all set tasks and foregone conclusions where every answer was to come from the artist’s own, subjective experience.[27] Many would come to see Vrubel’s work to be the incarnation of an archaic and pure condition and of an elemental cohesion lacking in the imperfect fabric of contemporary society.[28] Vrubel found a home within the Mir iskusstva group but still kept his style very much his own with a tendency toward a world of fantasy and painterly fable, a sort of mystical symbolism.[29]

Because of his inclination to remain individual, Vrubel’s art was often at odds with the age and his visual reality conflicted with other Symbolists. Wishing to portray an emotion or idea rather than a simple scene, his work is evidence of a deep, burning individuality and a multi-faceted symbolism with roots in the classical tradition, yet continuously drawn to the future.[30]

John Bowlt names Vrubel as the most original artist of the Russian Silver Age, whose “fertile imagination produced work of extreme power and originality.” Vrubel approached the act of painting as a constant process of experimentation, returning to his canvases again and again, erasing, repainting, modifying. His tireless restructuring of forms, his release of ornamental energy, and his intense elaboration of the surface prompted critics to speak of the crystalline formations, and “Cubist” faceting of his painting, to which the strangely lapidary flowers in his Demon Seated bear strong testimony.[31]

There is a sense of ethereality and dreaminess which characterizes Vrubel’s work. Vrubel developed a mystical and intuitive view of the Slavic soul giving his work a quasi-religious and mystical idealism in appearance. A proto-modernist, Vrubel sought to harmonize figures within their landscape by using strong ambient moods of color. He revealed in the mosaic-like structures, freer handling and decorative scale of his work, an aspiration towards the analogy of music, in their reliance on mood above content.[32]

Vrubel also understood how the figures of myth and legend had first formed in the popular imagination, emerging from the gnarled shapes of trees, the crouching potency of stone and boulder, and the play of life and air on tossing blossom. Vrubel absorbed and sought to show “Russian nature and human types, our present life, our past, our fantasies, dreams, and faith.”[33] The most important thing was to encapsulate the moment, to convey a mood.

As a symbol, the meaning the Demon took on changed as Vrubel’s interpretation of the world disintegrated. Consequently, the Demon became a psychological portrait which existed naturally in a real and contemporary landscape, giving the viewer a chance to gradually penetrate his mysterious world.[34] Vrubel’s Demon Seated starts out as the personification of the romantic spirit, full of hope and searching for love, beauty, harmony, and truth. He finds it in the love of a woman, but quickly loses it. In the end, he is crushed, disillusioned and cast out into a world which has no place for him. Throughout, Vrubel somehow is able to convey the duality of the age with a strange combination of the sadness and despondency characteristic of Symbolism, as well as a form of intellectual hope and romanticism. Vrubel’s development of the Demon theme demonstrates his technique in exhibiting how the visual, psychological, and philosophical ideas of the time can interact as an expression of the creative process.[35]

The contrast in Demon Seated and Demon Downcast, separated by only twelve years, demonstrates how much can change in a short time. Vrubel had the ability to show a combination of the nervous disquiet of the time with the monumentalism of the past.[36] When Vrubel began painting Demon Seated, modern art in Russia had only just begun to flourish. Social reform, rapid industrialization, and growing resentment for the Tsarist regime are only a few instances that describe this grave, gloomy period of expectation, doubt and despair, which caused the artist to refine man’s individuality, mortality, and solitude, as seen in Demon Seated.[37] Vrubel sought experience and subject matter beyond the norm and explored spiritual mysticism through a deep self-analysis and awareness of the subconscious.[38] Vrubel, as indicated by Bowlt, weighed the spiritual torment of the age against the judgments of the past that had stood the test of time, investigating the concepts of violence, denial, shock and utopian vision.[39] His Demon Downcast represented the tragedy of the intelligentsia, who sought knowledge and freedom, and through this struggle between experience, error, and invention they searched for self-discovery.[40] This Demon reveals the individual soul’s highest aspiration as it struggles to transcend the social pressure of the commonplace.[41] According to Aleksandr Blok, a Symbolist poet and contemporary of Vrubel’s, the Demon became “a symbol of the times…a spirit of revolt against society and an intermediary towards other worlds.”[42]

Just as the Demon of Demon Seated represents Vrubel’s era, so the Demon of Demon Downcast wholly represents the era as well. The left-hand side of the image, though chaotic at first glance, is expressing a sense of calm within the smooth flow of the wings and rocks. This peaceful atmosphere serves to somewhat mask the turbulent chaos of sharp edges and broken lines forming on the right. The resolved yet horrified expression, broken forms of the body and landscape, act as a vision of the end of the old order and the intensifying will to overturn and destroy.[43] Demon Downcast coincided in a time when “art was trying with all its might to illusionize the soul and to wake it from the trifles of the commonplace through powerful imagery.”[44] The resulting image displays the struggle between the infinite and eternal individual. His horrified expression and broken form are visions of the end of the old order and an exacerbated will to overturn and destroy. This Demon represents an archetype: the quest for the universal and tragic in nature with the fall from grace predetermined. His fate is to struggle within his own spirit. He is hideously misshapen and has the rigidity of stone. With the violent, broken, and opposing rhythms of the body and landscape, it is suggested that Vrubel himself had the foreknowledge of an impending apocalyptic crisis.[45]

The Demon of Vrubel’s world was, much like him, spurned by the everyday and left with nothing but to contemplate his own soul.[46] For the destructive passions of Vrubel’s own time, the young, pensive figure of Demon Seated stood as the new spirit of self-restoration. He recognizes his own uniqueness and looks toward the light for renewal. He is a combination of tremendous power and powerlessness. This Demon, as Mikhail Guerman asserts, possesses both “health and strength, and radical pessimism” yet, “an ardent faith in redemption.”[47]

In opposition, the Demon of Demon Downcast is the representation of the social injustice of man, who has set his mind and senses free only to become more acutely aware of the anguish of mortality in the “uncreated, purposeless void of existence.”[48] He is the suppressed dream, unneeded power, and loneliness which Vrubel allows to enter the viewer through the language of painting. With Demon Downcast he was able to convey, in a single motif, the drama of the age and the dilemma of eternity, all while remaining himself and individual.

Philosophy in Demon Seated and Demon Downcast

Believing that artistic activity was more than a reflection on nature, but also an intellectual pursuit, Vrubel became an avid follower of both Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche.[49] Vrubel’s Demon epitomizes Schopenhauer’s Will versus Representation and Nietzsche’s Apollonian versus Dionysian concepts. Both theorists advocated ways to overcome a frustration-filled and necessarily painful human condition through artistic forms of awareness. This awareness manifests itself through the concept of the Dionysian will of instinctual desires and the Apollonian representation of rationality which suggests that somewhere amongst the moral order and sober rationality of culture lies a life force containing the emotive, primordial nature of human beings which culture suppresses. The artist can attempt to bridge that gap between the truth of nature and the myth of culture, thus finding a means to pass through the suffering of life and attain beauty.[50]

Arthur Schopenhauer’s theory of Will and Representation has several key elements that can successfully be applied to Vrubel’s work. The general concept of his theory is that Representation is the world as it appears to the mind. This can also be called the Idea. Will is the world as it exists outside of thought behind the world of appearance.[51]

The world as Will is beyond description because we cannot know anything concrete about it and is, therefore, the underlying transcendental ground of the world as Idea or Representation. Schopenhauer proposes that it is possible at least, non-representationally, to arrive at an understanding of the world as Will. He suggests that we can only experience a transient world of chance appearance individuated by the mind’s innate categories and concepts under the principle of sufficient reason in which a true non-transcendental explanation exists for every aspect of the world as Representation.[52] Therefore, one can go beyond knowledge of transcendental reality through specifying another sense of nonrepresentational knowledge of the thing-in-itself, and by identifying a field of application in which this “knowledge” can function becoming, “not merely the knowing subject, but that we ourselves are also among those realities we require to know, that we ourselves are the thing-in-itself.”[53]

The world in reality, independent of the mind, is known as the thing-in-itself. The thing-in-itself, as Will, is the inner nature of everything and is described as a monstrous blind urging, an un-individuated force and power, or an endless undirected striving. Access to the thing-in-itself is an individual experiential will that we experience in everyday wanting and desiring, and it is particularly in the frustration of our wants and desires that we acquire some idea of the world as Will. Experience of willing discloses the nature of reality as whatever immediately objectifies desire, striving, urging. There is, however, a fine distinction between knowledge in the narrow sense, to which the thing-in-itself is unknowable representationally, and nonrepresentational knowledge that is not acquired by ordinary cognition, but by direct acquaintance with willing as the most direct manifestation of reality in the world of appearance. Will as thing-in-itself is only non-representationally revealed in something Schopenhauer described as much like a mystical experience.[54]

Demon Seated illustrates Schopenhauer’s world of Representation whereas Demon Downcast illustrates the world of Will. Although nature and the figure of the Demon are somewhat fragmented in Demon Seated, the image still represents objects that do exist within the real world of appearance. The figure of the Demon displays a calm reserve, although his strong, muscular body is tense. He appears, physically, to be on the verge of attack, but though he appears tense, his shoulders are slumped over and he sits in a child-like position while the forlorn expression on his face conveys that his tendency for self-destruction is immobilized.[55]

The Demon in this image is representative of the world as Idea or Representation. His body, though fragmented in appearance, is proportionate to an average human being. He is experiencing true sadness as he sits on top of the world, looking as far as he can see yet looking no further than what lies inside him. He is contemplating the world and coming to realize that there is something more to be found; not just the flowers enclosing in upon him to keep him safe, or the fiery sunset behind him which aims to destroy. He must decide if he wants to remain in the safety of where he is or dare to brave new offerings and journey into the unknown. The tear rolling down his cheek could be indicative of the choice he makes which is to roll against the wind and venture out into the void, knowing that there may likely be no point in which he can return to the reflective being he is while sitting there amongst the safety of the landscape.

In contrast, the fall of the Demon in Demon Downcast exposes the main idea of the Will, which is of a striving towards an end that does not exist. He has crashed amongst a strange mountainous landscape, landing in an unnatural position, yet his head remains upright. His eyes are possessed of a different emotion from the eyes in Demon Seated; he has seen how the world really operates and the sadness he once had is now replaced with hatred. His personal journey has led him to witness and experience all the world has to offer, yet the highest offering of love, was cruelly denied. With the loss of this love, he now must roam the earth lonely and desolate, with nothing to do but reflect on his failure to transcend his doomed destiny.

The Demon in this image is representative of the thing-in-itself and he has recognized that through his monstrous, blind urging he has actually become the thing-in-itself: Will. He gained access to Will through his desire for love and his frustrations in not being able to attain and keep that love. He experienced his own mystical experience through his brief encounter with Tamara as she perished in his arms and was taken to heaven by the angel. He has allowed this experience to permeate his being and the new emotion displayed upon his face is indicative of this tragic turn of events. He has allowed rage to possess him which has only caused him to fall further and further from grace. The fall does not bring death, as he wished, but, instead, brings only more suffering with the agonizing realization of his own immortality.[56]

The Demon can gain an understanding of this experience, if he chooses, through two channels: ascetic and moral suffering and self-denial or by aesthetic contemplation. Suffering is evident in both Demon Seated and Demon Downcast, although each is a different form of suffering. The suffering present in Demon Seated is the suffering that reveals itself as personally unacceptable. Through aesthetic contemplation, the Demon is momentarily freed from the representational world and given the chance to realize that life is essentially full of suffering. This observation is what sends the Demon on his quest for a new and different kind of world in which there is alleviation from pain. The journey he ultimately goes on leads him to the form of suffering seen in Demon Downcast. The Demon no longer cares about life, his or any other. Because he no longer desires anything, he is no longer susceptible to suffering however temporary it might be.

It is here that Schopenhauer introduces the ideas of beauty and the sublime. Schopenhauer describes beauty as the natural form of ideas and appears without effort. For him, beauty is defined as the natural form of ideas and appears without effort whereas the sublime is defined by the attitudes and emotional responses of the Will toward the world as Idea and requires a feeling of satisfaction that results only through the struggle and victory of the Will.[57]

Demon Seated demonstrates the idea of beauty. Here are the natural forms of the world, created by nature and untouched by the human hand. While displaying beauty, the image also gives us a representation of the sublime. In true, literal sense, the Demon sits, “the product of awe in contemplation of great distances in space and time,” in appreciation of the vastness of the world in front of him.

Demon Downcast wholly envisions the dynamical sublime with its great and terrifying confrontation with natural forces. Although no longer in awe of the mystery of nature, he is crushed before it threatened with a power that can destroy him at any given moment.

Although both images give a different impression of the sublime, they both ultimately create the same feeling: the threat of annihilation. Both representations of the Demon are of the “unmoved beholder” of the scene in which he lies, aware that he is “helpless against powerful nature” and “abandoned to chance”, knowing that the “slightest touch of these forces can annihilate.”[58]

They both display a different form of the tragic experience, as well. The demon seen in Demon Seated is the representation of the tragedy in which, at the sight of the sublime in nature, he chooses to turn away from the interest of the world and let his intuition take control. The demon of Demon Downcast is the catastrophic tragedy when the demon no longer strives to live but instead turns away from the will to life.

The delineation that humans impose upon things forces an object or event to turn against itself, consume itself, and do violence to itself. This violence sends one on a quest to find peace, and for Vrubel, the only means to do so was through artistic design. Through the act of creating, Vrubel believed that he would come to understand the abstract forms of feeling from everyday circumstances, in which he would then be able to perceive life without the burdens that typically cause suffering. He wanted to believe that he would come out on the other side, that he would, in Schopenhauer’s words, “pass through the fires of hell and experience a dark night of the soul, as his universal self fought against his individuated and physical self” in order to enter the “transcendent consciousness of heavenly tranquility.”[59] This search is seen in Demon Seated and it outcome is apparent in Demon Downcast.

Demon Seated is that vision of a lost soul, a melancholy figure who has withdrawn into an enclosed world wrapped in shadows and guarded by nature.[60] He sits there, staring into the distance, in contemplation of the eternal. The figure in Demon Downcast is no longer in contemplation. He has been cast out, isolated, dematerialized, and emasculated by his tendency to destroy as well as his guilt over his part in Tamara’s demise. He is a crushed, swooning body with tragic eyes; a pure spirit which looms out of the mist, dominant at last.[61] There is a sense of a deeper, more painful reality; an immensity and all-pervasive atmosphere that is intangible and mysterious. This demon embodies Vrubel’s concept of the soul’s essence as active and disruptive in the “eternal struggle of the mutinous human spirit” and in creative conflict with the world.[62]

Human desires which motivate human will far outnumber their momentary satisfactions; man is condemned to suffer and pleasure is merely a suspension of pain; respite from the human condition can only come by the distancing of the self from worldly preoccupations. Images reflect the despair as well as the hopes and aspirations of a generation adrift from a society they despised. A mood of disillusionment with politics, dissatisfaction with materialism, and a search for meaning forced artists to turn their backs on traditional, academic modes of expression and went in search of a new language of the spirit in art.[63]

Nietzsche understands art as the basic transformative impulse known to human experience. He proposed that art itself, as the unacknowledged catalyst of social change, growth, and transfiguration has a redemptive value to it. He states that, with the creation of art, we are actively contributing to the construction of the order and meaning in the world and thereby liberate ourselves from submission to the authority of the eternal and unchanging values of the world. By exposing a lack of values, rejecting their bogus authority, and justifying the order and meaning of objects and events, we see how we transfigure our relations to ourselves and events.[64]

Apollonian and Dionysian Dialycts in The Demons

Nietzsche’s ideas center on the concept of the Apollonian and the Dionysian. The origin of tragedy, which this theory envelopes, develops from the outcome of a struggle between two forces: Apollo and Dionysus. Apollo embodies the drive toward distinction, discreteness, and individuality. He moves toward the drawing and respecting of boundaries and limits and teaches an ethic of moderation and self-control. The Apolline artist glorifies individuality by presenting attractive images of people, things, and events. Dionysus, however, embodies the drive towards the transgression of limits, the dissolution of boundaries, the destruction of individuality, and excess.[65]

The Apollonian concept is about cognitive activity and the awareness of general forms. The Dionysian concept is about movement and sexuality, intoxication, and the absence of clear individuation of the self. Nietzsche presents both Apollonian and Dionysian as natural drives within human nature. Apollonian activity is not detached and coolly contemplative, but a response to an urgent human need, namely, the need to demarcate an intrinsically unordered world, making it intelligible for ourselves. All out cognitive activity, including logical reasoning, abstracting, and generalizing tendencies, are profoundly practical and are the ways in which we try to master the world and to make ourselves secure in it. Apollonian activity is thus subtly un-Schopenhauerian, for instead of simply expressing the idealism in Schopenhauer’s account of representation, it now makes the further point that this activity succeeds only through self-deception: having effected an ordering, we convince ourselves that it is really the way the world is. Dionysian activity is a drive demanding satisfaction but is not unintelligent and not devoid of cognitive activity. The Dionysian experience is one of enchantment, charm, and a heightened awareness of freedom, harmony, and unity.[66]

In basic appearance Demon Seated is the Apollonian image. Demon Seated shows a calm, reflective, and cognitive being. Because of the tension seen in the muscle of his body it is clear that he is attempting moderation and self-control; he is not yet on his destructive path. He dreams of what life could be like had he been able to experience and become aware of all the good that life has to offer. He is completely insecure in his life and mind yet appears to be quite content, though slightly sad, as he gazes into the distance. Although it is unknown what he is thinking, one can surmise that he is contemplating his life and trying to figure out where he went wrong; attempting to find some logical explanation for the things he has done; for his actions which have caused pain for others as well as himself. This demon is trying to figure out his place in the world and is unsure where his future lies but, for the moment, he is surrounded by some relief, enveloped in the comforts of nature with the large flowers to the right of the canvas. Yet, even with this semblance of safety, the Dionysian can be seen in this image as well.

The Dionysian aspect of Demon Seated is seen mostly to the left of the canvas as well as in the Demon’s body. As mentioned, there is great tension in his body, which, for the moment, is contained by an Apollonian desire for a belief that there is a reason for the way the world is constructed. Here the demon embodies, in mindset, the self-deception that Nietzsche says is created by the fiction-making of the Apollonian vision. But the tension in his body displays the frustration with such a world and his head turned away from the beauty of the flowers, also hints at what is to come for the Demon. The fury of the sunset behind him, to which he semi faces, foretells the life he will ultimately choose. He is disenchanted with the world of appearance and decides to unveil what we so often hide from ourselves. His destiny is not one of reason or beauty but one of uncontrolled desire.

Demon Downcast, on the other hand, embodies wholeheartedly the Dionysian drive and dissolution of boundaries. The entire image informs the spectator of the final outcome of the journey he began in Demon Seated. Here is a creature that is no longer a reasoning, sane being; he is now at a level of ecstasy that has erased all that was once charming about the Apollonian vision. Visually, the image of his body and the mountainous landscape in which he has been thrown melt into each other and distinctions between the two become difficult to discern. Psychologically, this Demon has destroyed himself. He is the epitome of the destruction of individuality and excess. The Dionysian experience of freedom and enchantment, which enticed him in the beginning, has led to a haphazard existence where harmony and unity no longer co-exist. He attempted the becoming and tried to make himself into a work of art, but as with most Dionysian experiences, he let the Apollonian slip away and was left with nothing but failure, disorientation, and destruction in his wake.

This double essence of the demon, his simultaneously Apollonian and Dionysian nature, could be expressed, in Nietzsche’s word, as “all that exists is just and unjust and is equally justified in both respects.” That is the world the Demon has created for himself; that he must always call his world.[67]

In “Towards a Psychology of the Artist” in Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche states that “for art to exist, for any sort of aesthetic activity or perception to exist, a certain physiological pre-condition is indispensable: intoxication.”[68] Thus, Nietzsche informs us that, in order to create and perceive art, we must follow Dionysus. The destructive, primitive forces that are Dionysus, are also a part of us and the pleasure we take in them is real and not to be denied. These impulses cannot simply be ignored, eliminated, repressed, or fully controlled; they will have their due one way or another and failure to recognize them will eventually give them free rein to express themselves with special force and destructiveness. The primordial unity that is created is like a child wantonly and haphazardly creating shapes and forms, and then destroying them, taking equal pleasure in both parts of the process, in both the creation and the destruction.[69]

As stated, both Demon Seated and Demon Downcast share Dionysian qualities. The Demon of Demon Seated is trying to deny that part of him that is Dionysian. He is doing his best to ignore and repress those desires, but as can be seen, his tears give him away because he already knows that he will fail at this endeavor and that Dionysus will take complete control. Because of his initial failure to recognize these instincts, the Demon of Demon Downcast is that expression of the Dionysian which has been given free rein and he truly is a special force of destructiveness.

Demon Downcast is the Romantic finale: fractured, collapsed, returned, and prostrated before an old belief, before the old god. The Demon here shows us a reflection of the eternal, primal pain yet a luminous hovering in purest bliss and in wide-eyed contemplation, free of all pain. With sublime gesture he shows us that the whole world of agony is needed in order to compel the individual to generate the releasing and redemptive vision. He has become entirely at one with the primordial unity, with its pain and contradiction; nothing but primal pain and the primal echo of it.[70]

In creative activity, we find the source of what is, in truth, wonderful in life and if we can find value and our own meaning in it we can love ourselves and love life. Art is thus the great anti-pessimistic form of life, the great alternative to denial and resignation as well as the great means of making life possible, the great seduction to life, the great stimulant of life: “Art as the redemption of the man of action – of those who not only see the terrifying and questionable character of existence but live it, want to live it, the tragic war-like man, the hero…Art as the redemption of the sufferer – as the way to states in which suffering is willed, transfigured, deified, where suffering is a form of great delight…A highest state of affirmation of existence is conceived from which the highest degree of pain cannot be excluded: the tragic-Dionysian state.”[71]

Both Apollo and Dionysus are present in every human. The tension between both is particularly creative and the combination of both is part of a defense against pessimism and the despair of life. Tragedy consoles us and seduces us to continue to live. Life in the modern world lacks unity, coherence, and meaningfulness; lives and personalities are fragmented and they lack the ability to identify with their society in a natural way. As humans, we enjoy tragedy in order to understand the ritual of self-destruction and gain insight into the human condition. We take pleasure in our demise as well as others because the dissolution of identity is both horrible and pleasurable.[72]

The Apollonian and Dionysian mark their reconciliation in tragedy. Both Apollonian and Dionysian share elements with each other, especially if they are ever to become conjoined. Apollo tries to veil Dionysus with optimism and in the process, creates the tragic. He tries to transform the repulsive thoughts about the terrible and absurd aspects of existence into representations with which it is possible to live. These representations are the sublime and the comical, whereby the terrible is tamed and disgust at absurdity is discharged by artistic means.[73]

Tragedy shows the spectator, for he has “gazed with keen eye into the midst of the fearful, destructive havoc of so-called world history and has seen the cruelty of nature,” that all that “comes in to being must be ready for a sorrowful end” and we are forced to look into “the terrors of individual existence.”[74] Controlled destruction of the tragic hero confirms that individuation is the primary cause of all suffering. The spectator finds pleasure in beauty and the illusion of meaningfulness because they witness the suffering of the tragic figure from an outside point of view. Our inner strength and Dionysian laughter are to be our means of overcoming the tragic.[75]

Demon Seated displays the strong tension between Apollo and Dionysus. This Demon knows that the world is fragmented, represented by the fragmented flowers beside him, and that there is no unity or coherence in modern life. He lacks the ability to identify with his society and has thus turned away from it, both figuratively and literally. The Demon of Demon Seated had found within himself the defiant belief that he could create human beings and destroy the gods, and that his higher wisdom enabled him to do so, for which he is now forced to do penance by suffering eternally. He sits in the serenity of creation in defiance of all catastrophes, and is merely a bright image of clouds and sky reflected in a dark sea of sadness. He is concerned, but not comfortless, as he stands aside for a little while, as the contemplative spirit who is permitted to witness the enormous struggles and transitions of existence.[76] He has discovered the delusion that thought reaches down into the deepest abysses of understanding existence, but for the Demon to even dream of correcting it, he himself at this point must transform into art.

The Demon of Demon Seated is the man of action. He is looking away from the world of safety and looking toward the world of the terrifying. He is questioning the character of existence and is slowly coming to terms with the realization that his entire existence rests on a hidden ground of suffering. He is beginning to come to terms with a decision that he probably feels he had no say in: the decision to live the Dionysian life and become the embodiment of the tragic.

The Demon of Demon Downcast is the sufferer. He is in great pain yet even with all this pain, his head is held upright, defiant and a sinister appearance of delight in his fall can be imagined. The Demon seen here has reached the “tragic-Dionysian state,” taking pleasure in his own demise. His eyes gaze in sadness, confusion, and defiance after what has disappeared, for what they see is like something that has emerged from a pit into golden light, so luxuriantly alive, so immeasurable and full of longing. Tragedy sits in the midst of this, taking delight, in sublime ecstasy, listening to a distant melancholy singing of delusion and woe. This Demon is now one of those beings that have fought the war that, out of necessity, needs tragedy as a restorative power. To achieve the magnificent blend which both fires the spirit and induces a mood of contemplation, he must now remember the enormous power of tragedy in order to stimulate, purify, and discharge his entire life.[77] He is now coming to terms with his sorrowful end as he looks into the terrors of existence.

Vrubel’s Demon as seen in both Demon Seated and Demon Downcast is representative of the world as the release and redemption of god, achieved each and every moment, as the eternally changing, eternally new vision of the most suffering being of all, the being most full of oppositions and contradictions, able to redeem and release itself only in semblance.

The Demon, both in Demon Seated and Demon Downcast is the embodiment of Dionysus and never ceases to be the tragic hero entangled in the net of the individual will. He sees himself as sophisticated and capable of Apollonian artistry, briefly raising himself up once more in Demon Seated, like a wounded hero, and by the time of his final descent in Demon Downcast, all his excess of strength, together with the wise calm of the dying, burns in his eyes with a last and mighty gleam. Here is the demon, intoxicated by Dionysus, who has become the work of art.[78]

The Demon can even be seen as an early prototype of the nihilist, wandering around with no real meaning, purpose, or value in his life. Unconcerned with morality, he rejects God, and attempts to overcome his depression through self-destruction.[79] The Demon is literally torn to pieces in Demon Downcast but through the defiance seen in his eyes, he is determined to overcome this challenge by being reborn again. As he lies, prostrated, against a fragmented landscape, the Demon emerges from his Dionysian intoxication to witness the horror of all he has done. His stare is fixed into the distance where, momentarily, he thinks he might rise out of his destructive state and witness the sublime and tragic as he once did in Demon Seated. This moment is brief, however, and the Demon quickly returns to the absurdity of living a strictly Dionysian existence.

It is evident that Vrubel admired Nietzsche’s cult of the tragic, irrational, disharmonious world, and through his art attempted to find a means to combine Apollo and Dionysus. He was deeply committed to the idea that the world was not stable and permanent but rather constantly changing, unsteady, and problematic. The artistic genius must contemplate ideas and create an art that portrays them in a manner more comprehensible, thereby communicating the vision to those who lack the power to see through and rise above the society in which they live.[80]

Vrubel’s Decent into Madness

Unfortunately, Vrubel did not wholly succeed at creating what Nietzsche described, due in part to not being able to overcome his own personal history. Throughout the 1880’s and 1890’s, there is no denying Vrubel was an isolated figure. By the end of the century, even after several high profile commissions had been received, including the commission to provide illustrations for Kushnerev’s special anniversary edition of Lermontov’s work, people were still unaware of his work.[81] And for the few who did, his work was not well received. All people saw was madness and monstrosity. It was often called naive, incoherent, and savage. His only consolation is that his work was appreciated by a small group of enlightened patrons.[82] Alexandre Benois, a fellow Symbolist and Mir iskusstva member, believed the cause of his lack of success was because he was the definition of a true decadent, seeing reality through a “spiritual prism” which channeled between his outer world and his inner world, where his most devoted memories and attachments lived.[83] But, for the most part, it suddenly appeared as if Vrubel’s theme of failure in relation to the Demon was all too real.

The period before the onset of his illness at the beginning of 1902 was one of intense activity, marked by opposing experiences of growing recognition, vilification, and neglect, all of which Vrubel increasingly reacted to. By the end of 1901, unable to tolerate contradiction, unable to sleep, and talking incessantly, Vrubel became violent, excitable, quarrelsome, and obsessed with affirming his own genius. He developed feelings of religious guilt and atoned for it by lack of food and rest. Between 1903 and 1905, Vrubel’s illness continued to change course, marked by wild mood swings and behavior and the hearing of voices. In May of 1903, his son contracted pulmonary disease and suddenly died. The death of his son caused great torment for him, believing it was punishment for his past transgressions. After March of 1905, he remained permanently hospitalized. Until his vision and coordination completely ceased to function in February of 1906, Vrubel remained creatively active, with only brief periods in which his work suffered. He died in April of 1910. Sadly, his illness gave him the most recognition and praise of his career, with his first one-man show, in Kiev in 1910, in which some 114 objects were shown.[84] Many describe the last decades of the nineteenth century as “Vrubel’s epoch.”

Demon Downcast was the last work on the Demon theme before he was committed to a psychiatric clinic. The Demon of Demon Downcast embodies the dualities of the age; he is heaven and earth, east and west, male and female, nobility and despair, joy and suffering. This Demon is the culmination of a tragic personal journey and the premonition of the imminent universal catastrophe that was to come. He is the ultimate expression of Vrubel’s schizophrenic sense of being and becoming, coinciding with the onset of insanity from which there was no return.[85] With madness increasingly creeping in on him, he was unable to set the work aside, almost as if the creation of the work itself was what kept him from a complete breakdown.[86] By this time the Demon had become associated with the sacred madness of artistic inspiration. Both Vrubel and his Demon are ambiguous and contradictory, consumed by pride and self-loathing; he is the creator and the destroyer; the muse and devoted follower. The Demon personifies the rebellious human spirit in the eternal struggle to reconcile conflicting passions and the search for knowledge but unable to find any answers on earth or in heaven. Vrubel interiorized this spirit, absorbing and assimilating him into his own human fabric.[87] Both experience a moment of revelation with the realization that the world is not one-dimensional and poor but transparent and free. With this realization comes a period of trials which begins when evil forces try to break in and, in the case of Vrubel, prove fatal.[88] He tried to adhere to the idea that an earthly paradise can be momentarily revealed and restored through love, yet those stormy passions can never be fully reconciled with this ideal.[89] Through this recognition and familiarity Vrubel humanizes the Demon. He felt what the Demon felt, alienated from the everyday world around him; a world he felt only caused suffering. He was left with nothing to do but contemplate the enclosed realm of his own soul.

Tortured by visions of divine persecution, hallucinating that strange figures were appearing in his life and work as punishment for past transgressions, he famously changed the way the image looked, even while it was on exhibit. Vrubel’s almost automatic, mechanical process of changing the appearance of Demon Downcast could simply appear to be the artist’s desire to get it perfect or the manifestations of his psychosis. Friends and viewers described him as feverishly altering and re-altering the Demon’s fallen expression, sometimes several times a day. The pose would become stranger, more tortured, more dislocated while the color scheme of the mountainous background became more vibrant and more enchanting. He kept his color palette limited, using shades of blue and purple, adding a decorative quality that further conveyed the spiritual condition, the suffering, and the alienation that Vrubel, himself, felt. There is a wholly human pain within his gaze and his fall only brings him more suffering and a complete loss of identity. The mighty spirit from Demon Seated, who strove to be boundless, is now the figure of Demon Downcast hovering between the sky and the mountain landscape, revolting against the injustices of heavenly and earthly life. His spirit, as well as Vrubel’s, no longer has more veils than his body.[90]

The object that had long been his fascination, that he took pity on, came back to betray him. Lermontov’s Demon haunted Vrubel throughout his life and under the personal strain to depict him perfectly, he went mad, “falling on mountain spurs in a sunset of lilac tinged with blue.”[91] They say the condition of aesthetic creation comes from struggling with fate and ultimately ends in being defeated.[92] This defeat can either lift you to enlightenment or cast you into obscurity. After Vrubel’s death in 1910, Benois described him as “a demon, a beautiful fallen angel, for whom the world was an endless joy and an endless torture.”[93] For many, the eternal fades and passes away. But Vrubel found that amidst the urgent questions of his time and the bloody answers provided by his reality, the demon came to both nourish and destroy, as well as shape his artistic and personal destiny, ultimately giving him his place in art.

Works Cited

“Arthur Schopenhauer,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy website, Accessed on 7 February 2011, http://plato.standford.edu/entries/schopenhauer.

Benois, Alexandre, The Russian School of Painting, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1916).

Bowlt, John E., Moscow & St. Petersburg 1900-1920: Art, Life & Culture of the Russian Silver Age, (New York: Vendome Press, 2008).

Bowlt, John E., ed., trans., Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902-1934, (New York: The Viking Press, 1976).

Byrns, Richard H., “The Artistic Worlds of Vrubel and Blok,” The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring 1979), pp. 38-50, http://0-www.jstor.org.library.scad.edu/stable/pdfplus/307798.pdf.

Elliot, David. New Worlds: Russian Art and Society 1900-1937 (New York: Rizzoli International Publishing, 1986).

Elsworth, John, Andrei Bely’s Theory of Symbolism, Accessed 30 January 2011, http://fmls.oxfordjournals.org/content/XI/4/305.full.pdf. p.321-332.

Emerling, Jae, Theory for Art History, (New York: Routledge, 2005).

Gorlin, Mikhail and Nina Brodiansky, “The Interrelation of Painting and Literature in Russia,” The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 25, No. 64 (November 1946), pp. 134-148. Accessed January 28, 2011, http://0-www.jstor.org.library.scad.edu/stable/pdfplus/4203801.pdf.

Gray, Camilla, The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863-1922, (London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., 1971).

Grover, Stuart R., “The World of Art Movement in Russia,” Russian Review, Vol. 32, No. 1 (January 1973), p.28-42.

Guerman, Mikhail, Mikhail Vrubel: The Artist of the Eves, (St. Petersburg: Aurora; Bournemouth: MirParkstone Press, 1996).

Howard, Jeremy, East European Art: 1650-1950, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Isdebsky-Pritchard, Aline, The Art of Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910), (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press: 1982).

Jaquette, Dale, ed., Schopenhauer, Philosophy, and the Arts (New York:Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Kemal, Salim, Ivan Gaskell, Daniel W. Conway, eds., Nietzsche, Philosophy, and the Arts (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Khachiyan, Nina, “Vrubel’s Demons,” Written Words website, accessed on 14 February 2011.

Lermontov, Mikhail, The Demon, Accessed 7 March 2011, http://www.friends-partners.org/friends/literature/19century/lermontov2.html.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings. Raymond Guess, and Ronal Spiers, eds., Ronald Spiers, trans., (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Pothen, Philip. Nietzsche and the Fate of Art (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002).

Pyman, Avril, A History of Russian Symbolism, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Reeder, Roberta, “Mikhail Vrubel: A Russian Interpretation of “fin de siècle” Art,” The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 54. No. 3 (July 1976,), pp. 323-334, accessed January, 28, 2011, http://0www.jstor.org.library.scad.edu/stable/pdfplus/4207296.pdf?acceptTC=true.

Schopenhauer, Arthur. The World as Will and Representation, Volume I & II. E.F.J. Payne, trans., (New York: Dover Publication, Inc., 1969).

Footnotes

[1] E.I. Ge, “Poslednie gody zhizni Vrubelja,” in Vrubel. Perepiska, Vospominanija o xudoznike, 221; as cited in Richard H. Burns, “The Artistic World of Vrubel and Blok,” The Slavonic and East European Journal, Vol. 23, No. 1, (Spring, 1979), 46.

[2] Aline Isdebsky-Pritchard, The Art of Mikhail Vrubel, (1856-1910,) (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press: 1982), 42.

[3] Roberta Reeder, “Mikhail Vrubel: A Russian Interpretation of “fin-de-siècle” Art,” The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 54, No. 3 (July 1976), 331.

[4] Nina Khachiyan, “Vrubel’s Demons,” Accessed 18 March 2011, http://www.ninakhachiyan.com/writtenwords5.php.

[5] Ibid, 101-102.

[6] Byrns, “Artistic World of Vrubel and Blok,” 46.

[7] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 114-119.

[8] Ibid, 4-22.

[9] Mikhail Guerman, Mikhail Vrubel: The Artist of the Eves, (St. Petersburg: Aurora; Bournemouth: Parkstone, 1996), 8.

[10] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 104.

[11] Ibid, 23.

[12] Mikhail Lermontov, The Demon, Accessed 18 March 2011, http://www.friends-partners.org/friends/literature/19century/lermontov2.html.

[13] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 95.

[14] Guerman, 60.

[15] Sergei Durylin, “Vrubel i Lermontov” (“Vrubel and Lermontov”), Literaturnoe Nasledstvo (1948), no. 45-48, 541-622; as cited in Isdebsky-Pritchard, The Art of Mikhail Vrubel, 100.

[16] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 99-102.

[17] John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book I: lines 37-63; as cited in Isdebsky-Pritchard, The Art of Mikhail Vrubel, 117-120.

[18] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 94

[19] Ibid, 2.

[20] Pyman, 3.

[21] Byrns, 38.

[22] Ibid, xii-5.

[23] Bowlt, Russian Art of the Avant-Garde, 26-28.

[24] Bowlt, Moscow & St. Petersburg, 67.

[25] Ibid, 67-69.

[26] Ibid, 161-176.

[27] Pyman, 99-128.

[28] Bowlt, Moscow & St. Petersburg, 69.

[29] Bowlt, Russian Art of the Avant-Garde, xxiii.

[30] Guerman, 7.

[31] Bowlt, Moscow & St. Petersburg, 201-213.

[32] Elliot, 9-30.

[33] Pyman, 17.

[34] Guerman, 90-124.

[35] Isdebsky-Pritchard, xx.

[36] Ibid, 44.

[37] Bowlt, Russian Art of the Avant-Garde, 5.

[38] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 45.

[39] Bowlt, Moscow & St. Petersburg, 28.

[40] Khachiyan, “Vrubel’s Demons.”

[41] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 17.

[42] Aleksandr Blok, Sobranie socinenij (8 vols.; M.: GIXL, 1962), V, 423; as cited in Byrns, “Artist World of Vrubel and Blok,” 46.

[43] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 117-120.

[44] Ibid, 40.

[45] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 117-120.

[46] Guerman, 55.

[47] Ibid, 56-59.

[48] Pyman, 14.

[49] Ibid, 35.

[50] Jae Emerling, Theory of Art History, (New York: Routledge, 2005), 26-30.

[51] Jacquette, Dale, ed., Schopenhauer, philosophy, and the arts, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 2.

[52] Dale, Schopenhauer, philosophy, and the arts, 4-5.

[53] Schopenhauer, World as Will and Representation Vol. II, 195.

[54] Dale, 2-7.

[55] Guerman, 136.

[56] Ibid, 136.

[57] Dale, 118.

[58] Schopenhauer, World as Will and Representation, Vol. I, 204-205

[59] “Arthur Schopenhauer,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 1-20.

[60] Gray, Camilla, The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863-1922, (London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., 1971), 62.

[61] Ibid, 32-33.

[62] Vrubel, Mikhail A., Anna A., and Aleksandr M., intro. A.P. Ivanov, Pisma k Sestre Vospominaniya o Khudoshnike Anny Aleksandrovny Vrubel, Otryvki iz Pisem Otsa Khudozhika (Letters to His Sister, Reminiscences about the Artist by Anna Vrubel, Excerpts from the Letter’s of the Artist’s Father), Leningrad: Gosudarstvennaya Akademiya Istorii Materialnoy Kultury, 1929; as cited in Isdebsky-Pritchard, Art of Mikhail Vrubel, 97.

[63] Ibid, 251-254.

[64] Kemal, Salim, Ivan Gaskell, Daniel W. Conway, eds., Nietzsche, Philosophy, and the Arts. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.), 3.

[65] Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings. Raymond Guess, and Ronald Spiers, eds., Ronald Spiers, trans., (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), xi.

[66] Kemal, 52-54.

[67] Nietzsche, 51.

[68] Pothen, Philip. Nietzsche and the Fate of Art. (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), 163.

[69] Nietzsche, xxiv-xxx.

[70] Ibid, 26-30.

[71] Ibid, 57.

[72] Ibid, xi-xix.

[73] Ibid, 130.

[74] Ibid, 40.

[75] Kemal, 60.

[76] Nietzsche, 75.

[77] Ibid, 98-99.

[78] Ibid, 51-54.

[79] Khachiyan, “Vrubel’s Demons.”

[80] Pyman, 99.

[81] Guerman, 76.

[82] Pyman, 108.

[83] Isdebsky-Pritchard, 38.

[84] Ibid, 20-32.

[85] Jeremy Howard, East European Art 1650-1950, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 211-213.

[86] Guerman, 130.

[87] Khachiyan, “Vrubel’s Demons.”

[88] Pyman, 332.

[89] Ibid, 231.

[90] Guerman, 124-130.

[91] Gorlin and Brodiansky, “Interrelation of Painting and Literature in Russia,” The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 25, No. 64 (November 1946), Accessed January 28, 2011, http://0-www.jstor.org.library.scad.edu/stable/pdfplus/4203801.pdf, 146.

[92] Elsworth, Andrei Bely’s Theory of Symbolism, 327.

[93] Reeder, “Mikhail Vrubel: A Russian Interpretation,” 332.