We asked three participants of our Art and Museums in Russia program in St. Petersburg: “If you could introduce everyone to 3-5 pieces of Russian art, what would those pieces be?”

Here are the students and the essential art works they chose:

Kimberly Gordy

Kimberly Gordy is a student at the University of Texas at Austin working to get a B.A. in Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies with a minor in history. Their interest is in medieval and tsarist Russia, and how creative pursuits such as art and literature shape the perception and flow of history. They have been studying Russian language in school for three years. Kimberly is in St. Petersburg for SRAS’s programs in both art and Russian as a second language.

Kimberly’s essential art focuses on the 19th century:

Ilya Repin’s Sadko (1876)

Of course, it’s not a real list of pre-Soviet Russian painters without having Repin on it. He’s a classic, and if you’ve found yourself on a website called Art in Russia, you probably already know who Ilya Repin is. But he’s a classic for a reason, and it’s always good to remind people of Russia’s favorite painter— he definitely earned his spot on my top five list. While Repin is known primarily for his realism works, my favorite thing he has made is a painting for the opera Sadko, sharing the same name. Repin’s Sadko is a dreamlike piece, painted in a way that captures the haziness of sea-bottom mermaids and the fantasy of the scene, and its enormous canvas is full of details to notice. An almost-transparent squid, the jewelry of the mermaids, the variety of corals arranged around the bottom— it makes it worth looking at for a long amount of time, since there’s always something to notice.

Ivan Shishkin’s Stones in a Forest, Valaam (1858)

Shishkin is a landscape painter, and I have a strong personal bias to anything relating to the ocean and anything relating to plants. Shishkin supplies all of the nature close-ups of plants one could desire. Stones in a Forest, Valaam is a personal favorite because it’s dark and feels a little lonely, while most of his plants that are displayed in the Russian Museum are nicely-lit patches of flower or grass within a forest. Stones has a different feel and to me involves the viewer more and feels more like a scene than a depiction. His scenes are soft natural colors, but everything stands out on its own despite the overabundances of browns and greens and despite the tendency towards smaller canvas size.

Ivan Bilibin’s Red Rider (1899)

Ivan Bilibin is probably the most famous illustrator of fables in Russia, and his illustrations commonly accompany anthologies of Pushkin fairy tales. His style is very distinctive: reminiscent of woodcuts, plenty of natural motifs, simplistic lining style, and almost always contained by a border of some sort. I love his art because of the simplistic and folkloric style of it, and folklore and tales have played such an enormous role in Russian culture that it feels wrong to make a list of art without some folkloric themes represented. Bilibin’s style is also unique among many of the famous Russian painters, because of the linear style and the tendency toward flatter coloring. It resembles a comic book, almost, a graphic illustration, and I very much like it. Red Rider contains all of the artistic themes and methods Bilibin is known for, and has a nice effect of the red color standing out very starkly against the green background, which was a less common device used by Bilibin. This painting depicts a scene from the tale of Vasilesa the Beautiful, where Vasilesa sees the horseback riders representing Dawn, Day, and Dusk riding around the hut of Baba Yaga, with this painting showing the rider of Day.

Ivan Aivazovsky’s The Ninth Wave (1850)

Aivazovsky is a well-known painter of seascapes, and his depictions of the ocean are beautifully lit and impeccably depicted. All convey their own emotions, and Aivazovsky mastered painting on scales varying between absolutely enormous and postcard-size. The Ninth Wave is a gigantic canvas showing dawn coming to sailors stranded after a shipwreck. Despite the sailors’ clear predicament, the colors give the scene a sense of hope. Light and color interact beautifully, and despite the limited subject of ‘sea and sky’, Aivazovsky uses a rainbow of colors to create a bright and beautiful scene.

Orest Kiprensky’s Young Gardener (1817)

Around the early 1800s, portraits started becoming more psychological, where the emotions and attitudes of the subject were visible in their portraits, rather than an austere deadpan or vague half-smile. Kiprensky was a painter in the age of Romanticism, and this portrait of an unnamed gardener presents a poetically Romantic expression. I prefer the psychological portraits, I like seeing historical figures as people with feelings like anyone else, and I especially like the portraits depicting an average human. Historically, it would be pretty difficult to run into Catherine the Great on the streets, but it’s easy to imagine seeing this young gardener hanging out on the corner— either in the 1800s or the current era. His face shows different things depending on the story the viewer wishes to invent, which I find a fun exercise in psychological portraits. Is he lost in daydream, thinking of a pretty girl, really hoping that his employer will tell him he’s got today off because he’s fantastically bored? This portrait is soft and expressive and I found myself standing in front of it for much longer than I expected, thinking up stories for this kid.

Sophia Fisher

Sophia Fisher is currently studying Russian as a Second Language with SRAS Saint Petersburg, Russia. Sophia believes that the exponential development of communication technology has made Russian language skills critical in all professional fields. In August, Sophia will return home to her native Ohio for a final semester at The Ohio State University, where she will receive a diploma in art history and Russian language. After graduation, Sophia plans on pursuing a career in arts management or public relations.

Sophia chose pieces from the early post-revolutionary period:

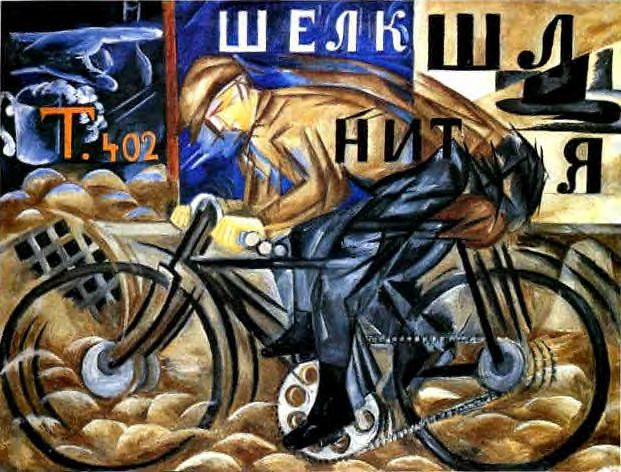

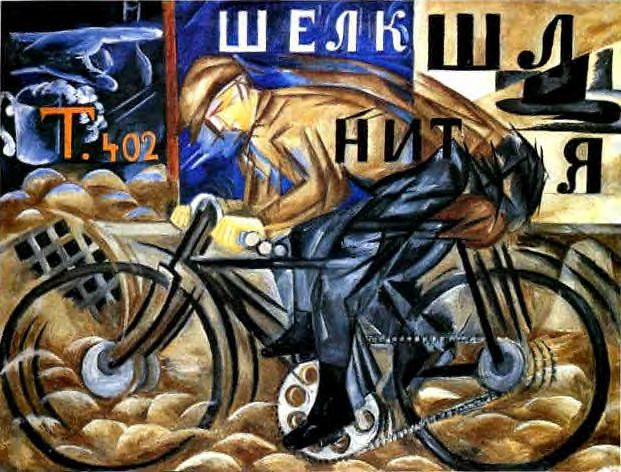

Natalia Goncharova’s The Cyclist (1913)

This is a hallmark piece of the early Soviet era, often appreciated in introductory art and film courses for its unique fractionalization and clear associations with cubism and futurism. In this piece, the multiplication of the figure and the bicycle are meant to indicate momentum and progression, two qualities treasured by futurist painters. Text alternates from foreground to backgrounds, suggesting impermanence and haste. Natalia Goncharova is widely recognized by Russians and their collecting institutions. Unfortunately, her work is relatively under-discussed overseas, as she is overshadowed by Malevich, Petrov-Bodkin and other male contemporaries. The Russian museum possesses a significant collection of her works, many of which are currently on display in the contemporary galleries.

Nathan Altman’s Portrait of Anna Akhmatova (1914)

Here is another Russian artist flirting with fractionalization. Anna Akhmatova, beloved Russian poet, was known for her great, birdlike features: her angular nose and wing-like shoulders. In Altman’s portrait, Akhmatova’s body mimics the forms of the geometric plants of the garden behind her. The refraction of objects behind implied glass, as well as the shifting non-linear perspective of the furniture and walls behind Akhmatova, make it very difficult to ascertain where Akhmatova’s interior world ends and the outdoors begins. Akhmatova seems resigned, her posture is intentional, but apathetic. This portrait certainly speaks to Akhmatova’s endless socio-political strife. Hers was a life under constant attack by the Stalinist regime, and reprieve from persecution and censorship seemed forever uncertain to the author. This work is also on display in the contemporary section of the Russian Museum.

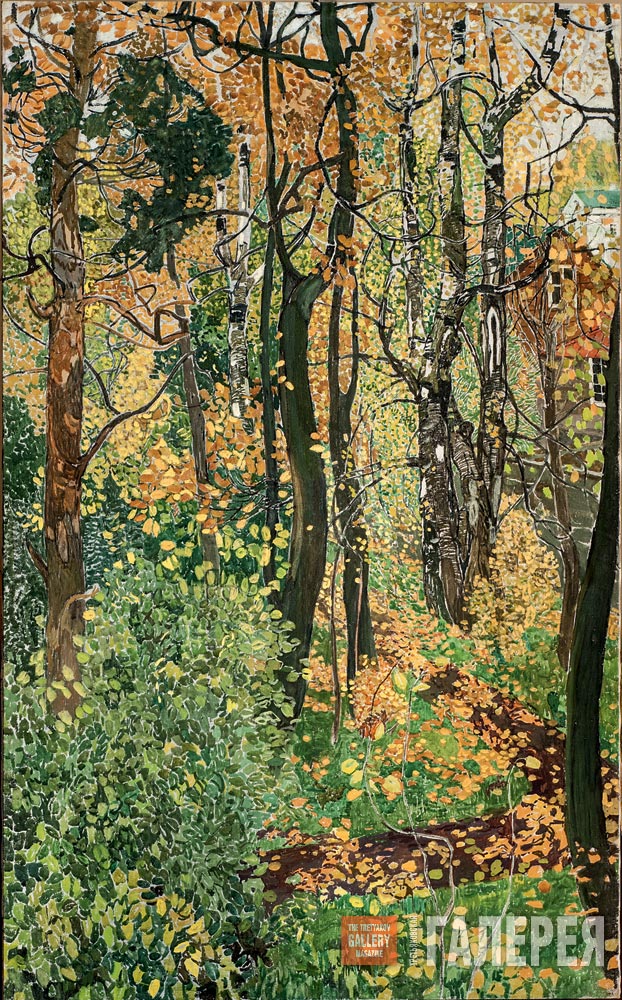

Alexander Golovin’s A View of Detskoe Selo (1920)

Golovin’s response to post impressionism is delightfully diverse and textured. The artist crowds his canvas with trees and plants. The dense span of these objects fills the entirety of the frame from top to bottom. Golovin creates depth with the definition of each leaf in the foreground, omitting this definition progressively from middle-ground to background and from bottom to top to really emphasize the impression of walking through the Russian woodlands. The skill with which he renders the bark of each tree and cast of light from the canopy is masterful. Golovin worked as a set painter in the Theater and his attention to light and color as a means of engagement and immortal is perhaps cultivated from his professional practice.

Evan Fishburn

Evan Fishburn is a senior at Boise State University, pursuing a degree in English Literature and a Certificate in Digital Media and Cinema. He appreciates the intersection of art, music, and literature, specifically as it occurs in the works of Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Tolstoy, and Turgenev. Evan’s interests include classical piano, short stories, poetry, and photography (find him on Instagram, @evanfishburn). He is taking part in SRAS’s Art and Museums program and is studying the variety of memorial apartment museums throughout St. Petersburg.

Evan Fishburn’s top art can all be found currently on display in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

Nikifor Krylov’s A Winter Landscape (1827)

This painting conveys the cold Russian winter and peasant life in the countryside. As they go about their duties, there is an apparent lightness and plainness, and Krylov’s conserved color pallete reinforces this simplicity. The composition feels balanced, where the distant pine trees and large horse in the foreground offset the two tall trees on the left side. It calls to mind the musical composition “January: By the Fireside” from Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons. Krylov is a master of winter painting; this is his only surviving landscape.

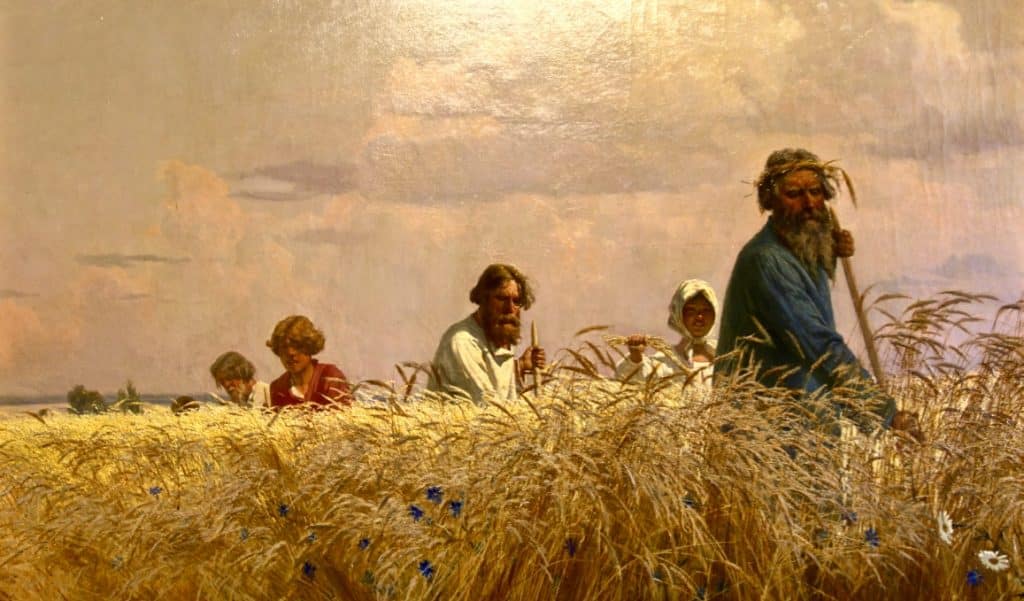

Grigory Myasoyedov’s Harvest Time (Scythers) (1887)

With warm tones in the clouds, wheat, and concentrated faces of the harvesters, Myasoyedov captures the heat and labor of this summer chore. It is an excellent example of Russian realism. This painting is reminiscent of the famous “mowing scene” from Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina and the musical composition “July: Song of the Reaper” from Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons. Located in the Russian Museum.

Vladimir Makovsky’s Dosshouse (1889)

Makovsky conveys the coldness and peasantry of Saint Petersburg in the wintertime by showing the red-faced destitute huddling together in crowds, breathing on their hands, and waiting to enter the cheap lodging, always with a look of despair on their faces. The scene is reminiscent of Dostoyevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment, giving humanity to the poor rather than castigating them.

Natalia Goncharova’s Cyclist (1913)

This painting is a prime example of avant-garde art and the Russian futurism movement, with visible influences from Cubism and graphic design. Goncharova shows the motion and speed of the scene by repeating brushstrokes in the cyclist’s back and legs and around the bicycle’s tires, as he races toward the future. In the context of Russian art, Goncharova’s work – and the way she conducted her personal life, openly living unmarried with a man – defies convention.

Boris Grigoriev’s Vsevolod Meyerhold (1916)

This is a portrait of the Moscow stage director Vsevolod Meyerhold, who was tortured and killed in one of Stalin’s Great Purges of the intelligentsia. Grigoriev, the painter, was a member of the World of Art movement; this painting is an example of expressionism. This portrait conveys the duality of Meyerhold’s legacy – playful,yet sinister – and strongly evokes the same mood of Bulgakov’s famous novel The Master and Margarita.

Evan Fishburn is a senior at Boise State University, pursuing a degree in English Literature and a Certificate in Digital Media and Cinema. He appreciates the intersection of art, music, and literature, specifically as it occurs in the works of Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Tolstoy, and Turgenev. Evan’s interests include classical piano, short stories, poetry, and photography (find him on Instagram, @evanfishburn). He is taking part in SRAS’s Art and Museums program and is studying the variety of memorial apartment museums throughout St. Petersburg.

Evan Fishburn is a senior at Boise State University, pursuing a degree in English Literature and a Certificate in Digital Media and Cinema. He appreciates the intersection of art, music, and literature, specifically as it occurs in the works of Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Tolstoy, and Turgenev. Evan’s interests include classical piano, short stories, poetry, and photography (find him on Instagram, @evanfishburn). He is taking part in SRAS’s Art and Museums program and is studying the variety of memorial apartment museums throughout St. Petersburg.