Our streets were paved in cobblestone; later that was replaced with asphalt. On the street corner stood a water pump for an underground spring where we would get water. Those disappeared from Moscow in the 60-s and now remain only in some villages.

The courtyard – classic Moscow court, surrounded by a heavy, tall fence, with a gate hanging on huge hinges, and breezeways on both sides. During the early years of my life, there also was a “yard-keeper” – a Tatar by nationality.

In my childhood, left to entertain myself, I liked to study rocks, which constantly appeared from the ground in our yard. Holes, left in the ground by streams of rain runoff falling from the roof, produced scattering of small colorful stones, split and polished to shine by years of running water. Two huge, age-old trees, which often offered cover for hiding, playing children, still stand in the middle of the courtyard. They are the only remnant of those times.

The building had only three “main rooms” with large windows overlooking the street. The former owners of the house occupied the largest of these rooms. Another large room, – at that time I thought it was the center of the house, – housed a widow of a Red Army officer.

Now I understand that people didn’t have many belongings, only the necessities, so rooms, even though small, often appeared spacious. There was no hot water, no washing machines, no refrigerators… The mysterious darkness of creaky stairway leading to the attic, covered with thick layer of dust and earth instead of flooring, mesmerized me. Throughout my whole childhood I collected within myself the sensations of that old house.

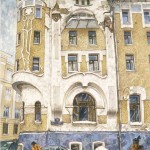

I lived in Kuzminki, in the south of Moscow, for four years. As soon as an opportunity presented itself, I moved to the Solyanka District, near the Kremlin. Building 1/2 Petropavlovsky Pereulok is often referred to as “the iron.” It was built in 1925 at the place where saloons and dens described by Gilyarovsky once stood. Infamous Khitrovka was located a block away from there. Many homes remained mostly unchanged from before the Revolution.

Movie scenes of “former life” were often filmed on our streets, with sounds of shots, rushing “museum” limousines, and passing Red Army cavalry. Now it would not be possible. Many buildings have been reconstructed; facades were only were left on some buildings.

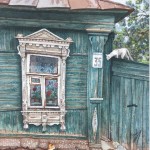

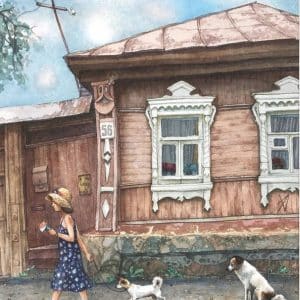

While walking through old Moscow my eyes unmistakably snag pieces and nooks still untouched by reconstruction, continuously carrying a hundred years of history within themselves.

I love the unique wrinkled faces of walls, pierced here and there by cables, a mesh of cracks, the “pocks,” “moles,” and “warts.” Often I see facades with “eyes,” “noses,” and “mouths,” smiling, yawning, or screaming. Nowadays they often undergo “cosmetic surgery.” The results are painful to see: it is like they received a fashionable “botox” injection, virtually a poison killing the facial muscles to smooth them out. As a result, instead of a face shaped by life itself, we get a smooth, dead mask.

Many of my watercolors of Moscow homes are portraits in nature, such as “Sivtsev Vrazhek,” “Sverchkov Pereulok,” “Yauzsky Boulevard.” My watercolor painting “On Solyanka Street” is a portrait of a remnant of an old fence, battered by life, living its last years, I think. Our surroundings are undergoing irreversible changes, which are probably necessary. At the same time, it is also painful, like the passing away of close, beloved people.

When I first begin to consider an idea for a painting, I take my time gathering “material:” I try to see the building or a location at different times of day, in different seasons, on weekends and weekdays, in the rain, snow, or sunshine. Different details on the building appear and disappear, like accessories on a woman. Buildings change their mood, their facial expression.

Several stages of work can be seen in the example of watercolor “Bolshoy Kazenny Pereulok”.

I hang my finished work on a wall in front of my eyes and within a few days, I begin to see my mistakes, which I try to correct.

But the main secret to developing a good painting lies in this: it must reflect that image of what has been drawn as it exists, above all, in the heart of the artist.