Art and Museums in Russia, a program of The School of Russian and Asian Studies, has given me some amazing opportunities in the past two weeks. The official program itself stops at nothing to expose students to as much of St. Petersburg’s art, architecture, and culture as possible. But when I asked program director Elena Varshavskaya if I could learn more about the Hermitage’s archaeological collections and the work behind them, she didn’t hesitate to arrange a tour of the collections for me, as well as a one-on-one interview with Hermitage curator Maria Menshikova.

A Tour through Time – The Hermitage Archaeological Collections

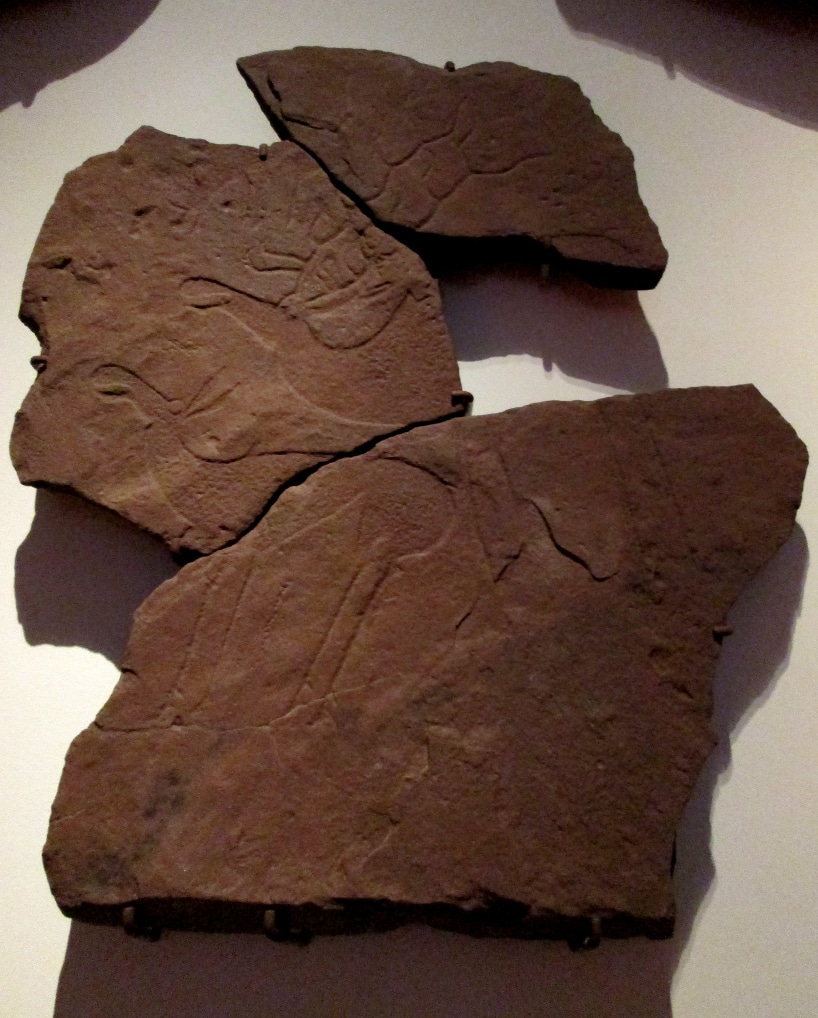

The collections I toured dated back as far as the eighth century BCE, with the nomadic Tuva steppe culture’s stone sculptures and petroglyphs. Within the Siberian Antiquities collection are artifacts from multiple Scythian burial sites, including from the Pazyryk Barrows and Great Altai Barrows, famous for the excellent preservation of their associated artifacts. Leather horse masks, wooden nails and tools, and even felt swan figures survived thanks to the permafrost of the region. Also displayed are the earliest extant pile carpet (made in the fourth to third centuries BCE) and mummified human and horse remains. The human remains are so well-preserved that it has been possible to accurately depict the tattoos on their skin–in fact, photos of these mummies and the recreations of their tattoos were in my archaeology textbook last year, as an example of uncanny preservation!

Decorative and funerary art objects from several cultures throughout the steppe region and throughout its history are housed in the Hermitage, including gypsum funerary masks found at Minusinsk Hollow dating to the third to fourth centuries, wooden sculpture and horse masks from burial sites of the Tashtyk culture, bronze work and inlay from the fourth to sixth centuries, oracle bones, and a variety of artifacts showing the development of both the runic alphabet and the riding stirrup following the arrival of Turkic peoples in the region.

In addition to these, the Hermitage also has an impressive set of collections excavated from abandoned cities along the former Silk Road, showing evidence of cross-cultural influences and incredible mercantile affluence. Sixth to eighth century coins, dice, carved chess pieces, and beautiful silverwork from Sogdian traders are displayed. Painted gypsum walls and reliefs recovered from the abandoned seventh to eighth century palace of Varakhsha (one of the westernmost outposts of the Silk Road) depicting Sogdian and Iranian heroic epics fill the rooms around the artifacts.

There is also a beautiful collection of mandalas, Buddhist and Taoist figures, masks, silk paintings, and print blocks from India, Tibet, and Mongolia, and statues and decorative art (including screens, jewelry, and porcelain) from China.

Interview with a Curator: Maria Menshikova’s Long History with the Hermitage

It is within these collections described above that Maria Menshikova, the curator with whom I spoke, does her work.

Ms. Menshikova fell in love with the Hermitage as a schoolgirl through the Children’s Studies program. Her father was a scholar of Chinese literature, so she was drawn to Asian art from the beginning. Although she passed her entrance exams for Oriental Studies, she was not allowed under the Soviet law to attend university because she had a Jewish grandparent. Since she couldn’t study, she started working at the Hermitage sweeping the floors. Within a few years, she was admitted to the university’s program for art history, and after graduating, worked her way up to the position of curator. She has now been with the Hermitage for more than forty years.

I asked her to tell me about her responsibilities as a curator, and was surprised to find out how many different jobs a Russian curator does! In the US, there is a pretty distinct division between academic, field, and museum work. Granted, there are some exceptions, such as research professors who do both academic and field work, but those jobs are generally few and far between compared to, say, Cultural Resource Management or archivist positions which focus on just one part of processing historic artifacts.

In Russia, a curator is responsible for nearly every aspect of the artifacts in their care. For any given piece, the curator assigns a catalogue number, files a catalogue card, writes reports on the condition of the artifact and recommendations for restoration and conservation measures to be taken to preserve it, writes the explanations and instructions for display, takes photographs, and enters it into both a computer database and inventory book. As they’re filled, the inventory books are sent to the Ministry of Culture for an official seal–once they receive this seal, it is illegal to alter them. If an object undergoes restoration, a condition report is written both before and afterward. For items sent to an exhibition, a whole new set of photographs, conservation reports, display instructions, inventory, and catalogue must be put together for the items sent. The curator has to procure insurance for all items sent, as well as working out safe ways to pack the items so they won’t be damaged during transport.

I asked how curators determine the best conditions for a particular artifact, and Ms. Menshikova explained that there are standard international rules for most things–display lighting, for example, can’t be over 55 lumes, and organic materials like wood and ivory are maintained in cool, controlled climates at around 50 percent humidity at all times. There are monitors displaying temperature and humidity levels inside the glass cases at the Hermitage, so it’s easy to check on the conditions.

What surprised me was that, in Russia, curators not only do all of the above-mentioned museum work (which is fairly standard in American curatorial positions, too), but also do the academic work related to their collections–giving lectures, researching the archives for historical records related to the artifacts, and producing publications–and even participate in digs at archaeological sites! Ms. Menshikova has gone on a number of digs, although Russian law now states that all excavated items must remain in the vicinity where they were recovered–so even if the Hermitage funds a dig (which it often does), the Hermitage does not get to add the artifacts to its own collection. Instead, a local museum must be set up for the new finds.

As for academic publications, she’s done some amazing work tracking down lost histories of artifacts (she calls it “archival excavation” because the archives got so mixed up during Soviet times). She has systematically produced a publication for every piece in her collections that had not already been written about–and is still in the process–and has researched, written, and lectured on additional collections whose history had previously been lost (including the silver filigree collection of the Czars), as well as on history and art history.

Live the Dream! Study Abroad!

I have loved everything I’ve seen in St. Petersburg through Art and Museums in Russia, but I can’t deny that this week’s immersion in the world of archaeology has made me positively hungry for my future career! From the excitement of seeing the artifacts themselves to the elation of having the opportunity to talk to someone who does, essentially, my dream job, this week has been an unforgettable experience for me.