Alexander Blok’s former apartment is now part of a two-floor museum complex. Blok was one of Russia’s primer Silver Age poets, and his museum shows not only how he worked, but also gives some indication of the emotionally extreme but also socially well-connected life he led.

The museum is located in the historic Kolomna district of St Petersburg on the bank of the Pryazhka River. This apartment was the Blok family home from 1912 until the poet’s death in 1921. Similar to many house museums in St Petersburg, Blok’s memorial apartment is difficult to find as the signage is very small.

This museum is not as accommodating to international guests as those museums dedicated to Golden Age writers closer to the main tourist areas in central St Petersburg. The workers speak little, if any English at all. Audio guides are only available in Russian. There is, however, a small book you can purchase at the entrance that explains each room of Blok’s apartment in English. This book must be purchased with cash even if you used a card to pay for your ticket into the museum.

The booklet provides the reader with a brief history of the museum. It informs that this museum was the first museum to be dedicated to Blok was opened on November 25, 1980 by the initiative of the State Museum of the History of Leningrad. Before the opening of Blok’s memorial apartment, the State Museum contributed greatly to the literary exhibition by providing personal items belonging to Blok and assisting in the memorial apartment’s reconstruction. After the museum opened, however, it became its own entity.

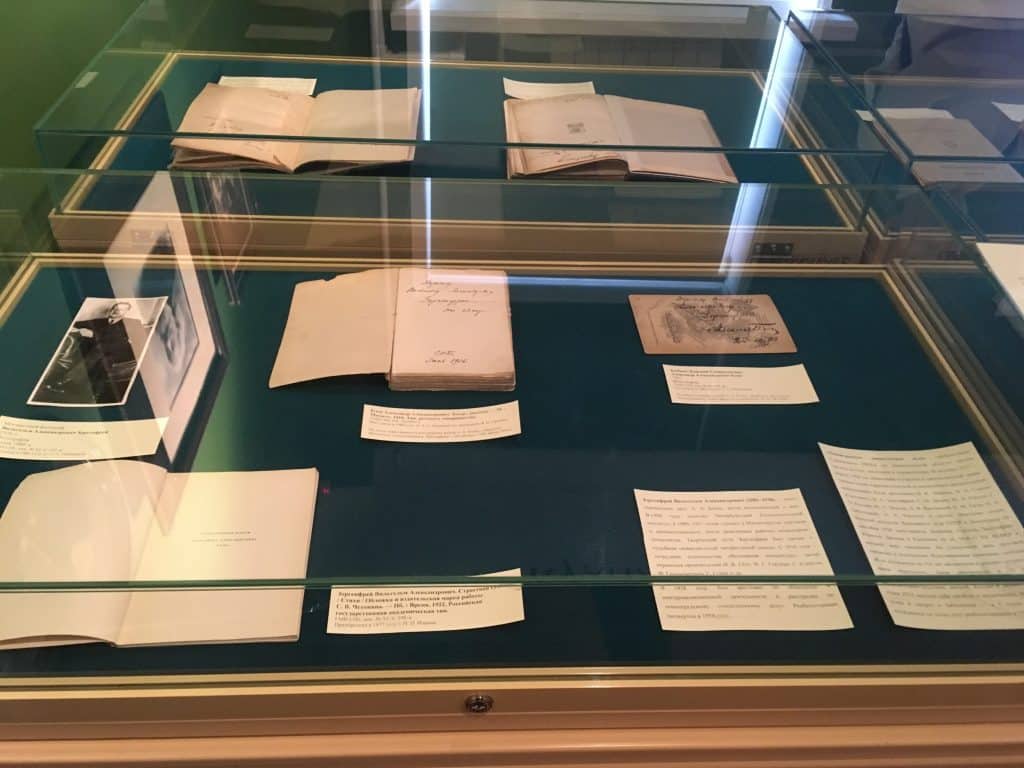

Upon entry you are informed (in Russian) that there are two floors to explore, the second floor hosts a literary exposition and the fourth floor is Blok’s memorial apartment. The third and first floors are not open for visitation. If you are an English speaker, the literary exposition is nice to look at but difficult to follow as you are offered no translations and everything posted is in Russian. The booklet only offers information about his apartment, not the exposition, which tracks Blok’s literary and artistic life in St Petersburg at the turn of the century. On display are a variety of original manuscripts, books, drawings, and personal items that once belonged to Blok. The exposition also highlights the poet’s final office in the second floor apartment which he worked in from 1920 to his death in 1921.

The majority of Blok’s life in his small fourth floor apartment was spent in his study. It was in this study that he wrote: “Jambs,” “Terrible World,” “My Country,” “Carmen,” “Scythians,” “Garden of Nightingale,” “Retribution,” “The Twelve,” and his play The Rose and the Cross. His works were prominent in the Russian symbolist movement which is characterized by experimentation and allowing meaning to flow from associations from and between imagery and ideas. Thus, the museum seems to argue that Blok’s literature is inextricably linked to his life in this apartment and by extension his life in St Petersburg. The museum also uses items once belonging to Blok as symbols to paint the picture of his life.

Blok’s study, according to the booklet, was the center of literary life in St Petersburg. In diary entries on display, the visitor can see the various artists that gathered in this apartment to visit Blok. The list includes but is not limited to: Anna Akhmatova, Andrey Bely, Alexander Benois, Vyachslav Ivanov, Elizaveta Kuzmina-Karavaeva, Osip Mandelshtam, Vsevolod Meyerhold, and Korney Chukovsky. This further demonstrates Blok’s importance to the literary culture in St Petersburg as he was a link between many important writers.

Blok’s original desk is the focal point of the study and once belonged to his grandmother Elizaveta Beketova. The desk acts as a symbol for the importance of family to him. Otherwise the room is minimally decorated with some seating and a large book collection kept in enclosed bookshelves. The booklet notes that Chukovsky once wrote how neat and tidy Blok kept his creative space: “the order which reigned on the desk was so remarkable that it was impossible to imagine any old bethumbed ragged manuscript on it. […] It seemed to me that things lined up themselves following geometrically correct lines.” The desk is recreated using this description. On display are pens used by Blok, an inkwell, items for smoking, and original manuscripts. Similar to his desk, Blok kept his writing neat. He would write on the middle of the paper to leave room for notes, edits, and illustrations.

Whilst Blok lived in this apartment, he accumulated a large collection of more than 3,000 books. In his free time, the booklet informs, Blok loved to visit antiquaries to further build his literary collection. He collected a variety of foreign and old books as well as old magazines. Lyubov Blok, Blok’s wife, specified in her will that the poet’s library be kept in the Institute of Russian Literature of the Academy of Sciences, also known as The Pushkin House. To this day, his personal collection is still on display there.

Like Blok’s study, the dining room was also a meeting place for literary figures in St Petersburg. Blok would frequently host long tea parties with talks that lasted hours. The room is small, but welcoming. In the center of the room sits a table big enough to seat six guests. On display in the corner is Blok’s samovar, a symbol of hospitality and culture in Russia, that Blok’s wife, Luybov would sit by and pour tea for the pair’s guests.

It was in this dining room that Blok first received Sergei Esenin, at the time an unknown poet, who came to show Blok his works in poetry right after he arrived in St Petersburg. It was also in this room that Blok hosted the great theater director and father of method acting, Konstantin Stanislavsky. The pair had dinner and discussed for hours the theatrical rendition of Blok’s drama The Rose and The Cross. Furthermore, on display on the wall is a scenery sketch entitled “A Castle Courtyard” which was made by Mikhail Dobuzhinsky, an expressionist painter famed for his cityscapes, for this performance. However, the play, in the end, was not staged in Blok’s lifetime.

Lyubov’s room acted as both a study and a drawing room and demonstrated her interests: she was an actress, art critic, and collector. Unmentioned is that she is the daughter of well-known Russian chemist, Dmitry Mendeleev. When she was younger, Lyubov graduated from Bestuzhev Courses, a higher education institution for women in St Petersburg. She also attended acting school and did some stage and film acting as well as tried her hand at poetry. Her education helped her receive various roles on the stage. Blok, however, did not believe Lyubov was a talented actress.

On display is a note from Blok to Lyubov where he writes: “reading your letters, I realized that you can leave the stage. I am sure that someone who doesn’t have an exceptional talent should do so.” This note is left without any further explanation, allowing the symbolism to do its part. One can infer from this note alone that the pair had a passionate and sometimes tumultuous relationship. Lyubov was the heroine of his first book of poetry and often referred to as the “Beautiful Lady.”

The room is warmly decorated with lace, paintings, and a large piano. In her free time, like Blok, Lyubov loved to collect antiquities. Many of her finds including porcelain pieces and old embroideries are still on display. Her favorite find, a pink chaise, remains part of the exhibition.

The final room is not mentioned in the booklet. This green room houses a display of a variety of Blok’s original manuscripts. Also on display is a shirt that was frequently worn by Blok as well as several pieces of art from his collection. Similar to the literary exposition, the signage in this room is only in Russian.

In this apartment, Blok lived through the changing social and political atmosphere of St Petersburg, after the First World War and the 1917 Revolution. In the last years of his life after the revolution, his life changed dramatically due to food and electricity shortages. Thus, like many other writers, he was forced to find other work and live a “bare existence.” Despite this, he originally supported the Soviet regime. Although he was busy with outside work as he was appointed to various Soviet organizations, committees, and commissions, he continued to write poems that are still read to this day.

Shortages in the Soviet era, however, eventually began to take a toll on Blok’s health. In his last two years Blok suffered from cardiovascular disease, asthma, and scurvy. During this time period Blok wrote that: “it has been almost a year that I do not belong to myself, I forgot how to write poetry or think about poetry. I cannot escape from small worries. I am fatigued to dementia. I have to think about meals, reports, firewoods (sic), fees, etc.” This short diary entry is symbolic of his losing faith in the Soviet government. He also suffered with boats of delirium before his death on August 7, 1921.

At the end of the booklet, the museum makes its argument clear: “Blok spent the seven most fruitful years of his life in this apartment. It was here that he wrote poems for the second and third volumes of his lyric poetry.” His poetry was often, like many Russian symbolists, combined paradoxically the mystical with the mundane, the idea of being detached from everyday life while searching for meaning is a main thread throughout Blok’s works. His writing is forever linked to this tumultuous period in St Petersburg’s history.

The Alexander Blok Apartment Museum

Address: 57, Ulitsa Dekabristov

Hours: Open daily from 11 am – 6 pm, except closing at 5 pm on Tuesdays. Closed on Wednesdays.

Price: Adults $160 RUB, students $110, English translation book $60 RUB