Much as the romantic ideology attached to the “Wild West” captivated the imagination of the United States in the second half of the 19th century, the primal beauty, proud warriors, and wild culture of the Caucasus regions fascinated Russian writers and heavily influenced Russian literature for centuries. However, this fascination was accompanied by years of conflict emerging from the revolutionary movements of Sheikh Mansur Ushurma at the end of the 18th century, to the full-scale military campaign of Imam Shamil, lasting until 1859. These conflicts gave rise to an intense xenophobia, which in turn fostered an aversion to constructive societal interaction between both the Russian and Caucasian cultures that has continued even into the modern age.

During the 19th century circumstances arose through which specific forms of cultural intermingling could take place. Historian Thomas Barrett frames this intermingling as a cultural “middle ground,” which was founded primarily on intermarriage, frontier exchange, and traditions of mountain hospitality. He describes the process of acculturation from the North Caucasus to Russia, and vice versa, as an occurrence most often arising from desertion, flight, or captivity (Barrett, 13). However, in the early 19th century, Russian writers created definitive barriers between the two cultures in their literary works that seem to muddy the waters of both Barrett’s concept of middle ground interactions and his stipulations for acculturation. Characterization of the relationship between Russian and Caucasian cultures is almost categorically represented in the works of these writers by profound hopes or ideological goals, which are then dashed by the inability of the cultures to coexist. This paper will explore the inadequacies in Barrett’s theory through an analysis of selected works of fictional references of Caucasian and Russian cultural interaction, and their portrayal of the perceived means of acculturation by Russian authors of the 19th century.

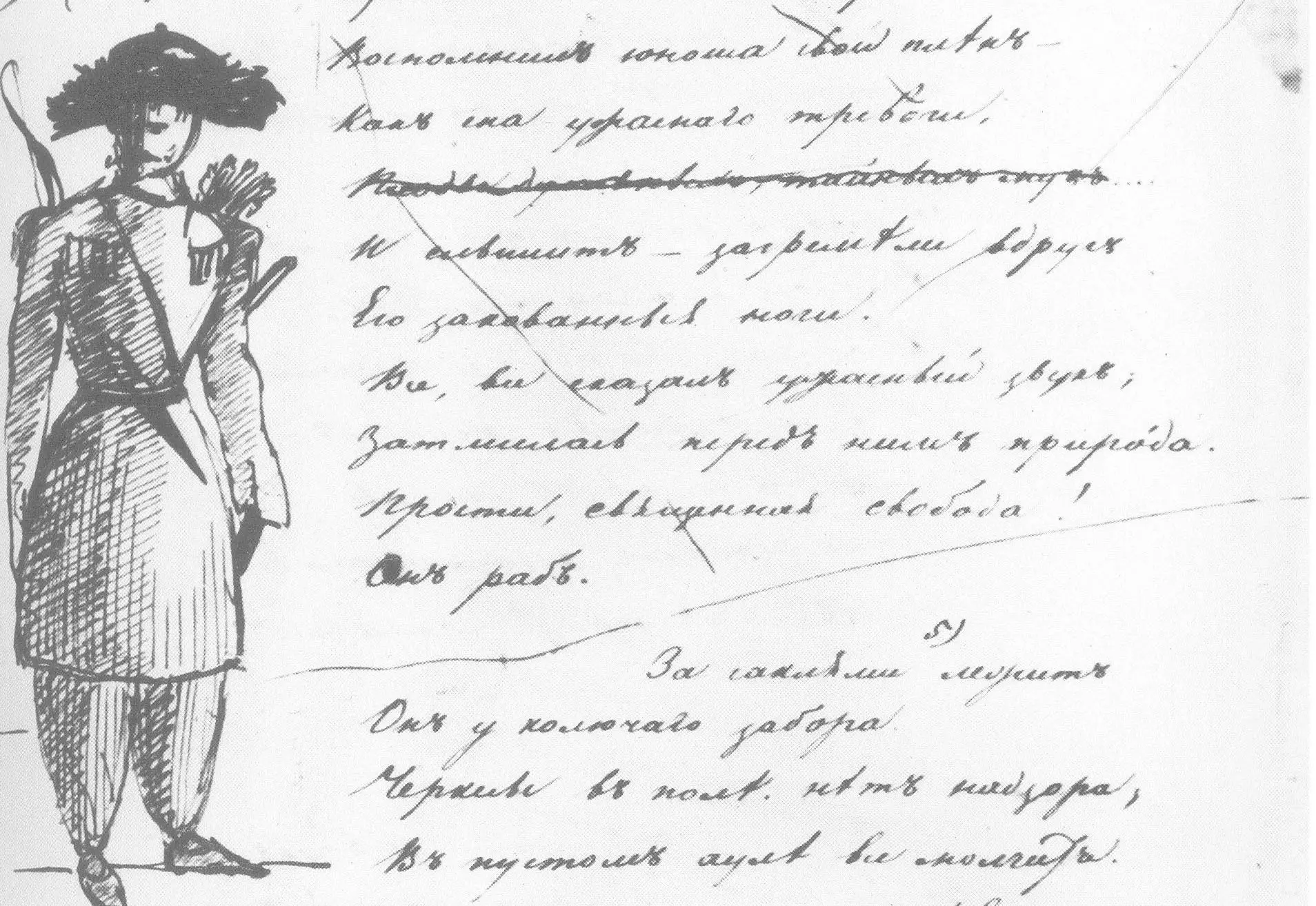

I. Pushkin (1799-1837)

Alexander Pushkin’s poem Prisoner of the Caucasus romanticizes Caucasian-Russian cultural conflicts. In this both highly imaginative and erudite poem, Caucasian traditions and cross-cultural interactions are witnessed through the eyes of a Russian captive who is characterized more as a confined spectator than as a prisoner. While this context conforms to Barrett’s proscribed external catalysts for interaction, the captive’s perception of the Circassians is illustrated through Pushkin’s fictional perspective of traditional North Caucasian culture, thus contradicting the concept of a process of acculturation. Pushkin’s depictions of violence, portrayed in the festival of Bayram, are met with ambivalence on the part of the captive:

«Нередко шашки грозно блещут

В безyмной резвости пиров,

И в прах летят главы рабов,.» (Pushkin, 103)

(“Sometimes in the wild exuberance of Circassian festivities there’ll be a menacing flash of swords, and the heads of slaves will tumble to the dust.”) (Pushkin, 139)

Despite the intensity of this imagery, the captive is not impacted by it:

«Но русский равнодушно зрел

Сии кровавые забавы.

Любил он прежде игры славы

и жаждой гибели горел» (Pushkin, 103)

(“The Russian witnessed these bloody entertainments with indifference. In earlier life he had himself been fond of daredevilry and had burned with thirst for bloodshed.”) (Pushkin, 139)

In response, the Circassians express admiration towards their captive rather than animosity. Pushkin’s voiceless Circassians marvel without words at the Russian captive’s “pluck,” and eagerly congratulate each other on such a valued prize (Pushkin, 104).

While he is uncommonly unfazed by bizarre violence, what draws the captive even closer to Caucasian culture is the nurturing hospitality of a Circassian girl. The blossoming relationship between them is an integral catalyst to the events culminating in the tragedy of the poem. Offered a chance to live in freedom with the Russian captive by fleeing the aul (fortified village) of her family at the end of the poem, the girl is unable to bring herself to accompany him. Willingly, she casts aside a chance at a new life with the man she has come to love. Even at the point of her death, she cannot, as her final act, remove herself from her native culture(Pushkin, 112). Pushkin uses the Circassian girl’s internal conflict regarding her relationship with the Russian captive to represent the barrier between the Russian and Caucasian cultures.

Through this developing love story and the captive’s detachment, a good portion of Pushkin’s poem actually casts the Russian captive’s situation in a positive light; despite his loneliness and grief, some of his time amongst the Circassians can be seen as almost relaxing. Pushkin’s imagery in Prisoner of the Caucasus was not, in fact, based on firsthand experience but on Pushkin’s imagination. As a punishment for his earlier more scathing writings regarding the Russian aristocracy, particularly Odes to Liberty, Pushkin was sent to Pyatigorsk in the Northern Caucasus, where he had an extraordinary view of the Caucasus Mountains, yet was not able to witness what an actual Caucasian aul looked like. His inability to interact directly with the Caucasian culture prompted him to romanticize this culture (Layton, 91).

England’s Lord Byron wrote similar tales, particularly The Prisoner of Chillon, which directly influenced Pushkin’s poetic, romanticized depictions of the Caucasus (Layton, 65). Both poems comprise overarching subjects of fear and loss, and touch upon similar more intricate themes of assimilating to one’s place in prison, and what it truly means to be free. Byron’s excesses are a visible influence on Pushkin’s grandiose descriptions of the world of the Circassians. Both Byron’s and Pushkin’s prisoners gain a sense of deference towards their surroundings within the bounds of their captivity. However, Pushkin removes an element of Byron’s version of the story, in that his captive cannot find peace with his surroundings. In this regard, he is isolated from Caucasian culture, from the love for the young maid who cared for him, and from his environment. In contrast, Byron allows his captive to transcend himself and become part of the circumstances in which he is found. This important difference in Pushkin’s romanticized Caucasian image paved the way for others to develop Russian perceptions of the culture of the Circassians in future writings.

Pushkin awakened from this romanticized dream of the Circassian culture when he returned to the Caucasus in 1829. His resulting work, A Journey to Arzrum is an impressive geographical and historical work. Although not as widely praised as one of Pushkin’s finer literary works due to its stark realism, conspicuous fragmentation of subject matter, and purely documentary data on the Caucasus and Transcaucasia, it certainly represents a clearer image of the Caucasus. (Langelben, 90) Prisoner of the Caucasus, despite the later, clearer account, however, was to be Pushkin’s lasting influence on Russian portrayals of Caucasus culture. It was this original poem that so skillfully crafted the tempestuous relationship between Russian and Caucasian cultures portrayed in the literature of the 19th century. Although he refined his understanding of the Caucasian reality in A Journey to Arzrum, Pushkin’s imaginative portrayal of the Caucasus in Prisoner of the Caucasus, and the cultural conflicts therein, seemed more in tune with the Russian concept of barriers that could be only partially transcended.

II. Lermontov 1814-1841

Mikhail Lermontov, a contemporary of Pushkin, also wrote several works set in the Caucasus. Unlike Pushkin, Lermontov had extensive experience in the Caucasus as a Russian officer, giving him far greater insight into local traditions but also a clear experience of a divide between himself and the populations with which he interacted. In several of his works, Lermontov depicts a barrier between Russian and Caucasian cultures similar to Pushkin’s. Additionally, like Pushkin’s protagonists, several of Lermontov’s characters fit the form of the Byronic hero—particularly, for example, Pechorin in A Hero of our Time. Pechorin, like Pushkin’s captive, is not fully capable of crossing the cultural barrier, and yet strives to interact with it nevertheless. This is clearly evident in Bela, the opening story of Hero, in which each character is put in situations that challenge his or her willingness to interact with Russian or Caucasian culture. A tacit barrier of some sort prevents each character from wholly assimilating into the foreign culture. Pechorin is disillusioned with his relationship with Circassian Bela. Despite his desire for her, Pechorin is a foreigner in a foreign land, and is not able to adopt aspects of Caucasian tradition to his personal advantage, leading to an acerbic relationship with Bela. As the story unfolds, Bela is presented with an opportunity to be accepted by Christ, and thus permitted to reside in eternity with her love, Pechorin, upon her death. The offer is met with reticence and, eventually, refusal on her part. (Lermontov, Bela, 31) Lermontov depicts Pechorin as desiring to interact with and impact the Caucasians that surround him, but Pechorin’s efforts end in failure due to his inability to fully commit himself to the culture that he manipulates in his effort to acquire Bela.

In many of Lermontov’s other works as well, a Russian character may recognize his inability to grasp the Caucasian culture and at the same time profess his sorrow based upon that realization. In his lengthy poem Valerik, Lermontov recollects his experiences at the Battle of the Valerik River in 1840 and attests to the high regard in which he holds the Caucasiansagainst whom his country waged war for his entire life. Even on the field of battle, «в этих сшибках удалых» (“amidst the clash of swashbuckling steel”), as Lermontov writes, his immediate reaction is neither fear, nor hatred, but rather: «Мы любовалися на них, Без кровожадного волненья» (“We admired them all, without bloodthirsty tumult”) (Lermontov, Valerik,113). Although its depictions are less romanticized than those of A Hero of Our Time, the poem holds the dramatic themes of conflict between the Russian and Caucasian cultures, while also frequently touching on the majestic qualities characteristic of descriptions of the region in the literature of the 19th century. Lermontov’s choice of words to describe the Caucasus Mountains themselves, «Вечно гордой и спокойной» (“eternally proud and peaceful”) (Lermontov, Valerik, 216), can be interpreted in several ways. The Caucasus Mountains witness the bloodshed and carnage wrought by the harrowing battle, but are unmoved and unshaken, maintaining a stance of pride. This pride, which can be read as that of the Caucasian people as well, cannot be adulterated by Russian influence, even in the face of tremendous loss at Valerik. Lermontov poses the question of why there seems to be no hope of harmony between such deadly foes, yet cannot find an answer himself.

III. Tolstoy 1828-1910

Further examples of cultural conflicts are evident in the works of Leo Tolstoy, whose writing represents some of the quintessential depictions of the Caucasus in Russian literature. Like Lermontov, Tolstoy was able to leverage his firsthand experiences in the Caucasus to accurately describe significant cultural nuances of the region in his writing. Unlike Pushkin’s compositions, Tolstoy’s works seek to dissect and dismantle the romanticism commonly used to describe the Caucasus and to mock common cultural stigmas used in Russian literature, breaking them down with harsh realities. The barrier of a cultural impasse is maintained, yet from a standpoint of parody (Layton, 241).

The character Olenin in The Cossacks serves as an interesting example of this theme. The story begins with optimism and dreams of limitless potential. Olenin, a Russian aristocrat who has enlisted in the Russian army solely to travel to the Caucasus, desperately seeks to transition from his old life of seeming decadence in Russia into a life matching the pristine nature of the Caucasus. Like the heroes of other Russian authors, however, he confesses his internal struggle to achieve his goal of losing himself to the Caucasus and the deep affections he has for a young Caucasian girl. (Tolstoy, 493) Try as he may, Olenin is still a representative of Russian culture in his own mind’s eye and the in eyes of the surrounding population. The crux of this dilemma is conveyed in the final lines of the work, when both Eroshka and Maryanka, the primary Caucasian characters with whom Olenin interacts throughout the course of the piece, seem to disregard any trappings of emotional connection that had existed between them and the young Russian soon after he departs. (Tolstoy 520) Further, even after definitively disavowing Russian culture and vehemently lambasting it, Olenin is not capable of becoming part of Caucasian culture. (Tolstoy, 490)

Olenin’s inability to fulfill his romantic interest in Maryanka also serves as a representation of his inability to subsume his Russian persona in favor of a Caucasian one. Maryanka is frequently compared to the natural beauty of the Caucasus, and Olenin himself refers to her as such:

«Я любовался ею, как красотою гор и неба, и не мог не любоваться ею, потому что она прекрасна, как и они.»

(“I delighted in her beauty just as I delighted in the beauty of the mountains and the sky, nor could I help delighting in her, for she is as beautiful as they.”) (Tolstoy, 491)

Maryanka, as a representative of Caucasian culture and life, is ethereal to Olenin, just as the culture that she represents. He cannot interact with this culture as he wishes, let alone maintain connection with it, because it is so profoundly separate from his own understanding of culture intrinsic to him as a Russian.

Tolstoy’s last novella, Hadji Murad, provides another example of this conflict. Its introduction, depicting the narrator’s removal of the thistle from its natural place of repose in an open field flowers, though seemingly simplistic in nature, is symbolic of the entire Caucasian culture as a whole, and its perceived hostile relationship with Russia. Tolstoy’s use of this framing narrative mirrors the repercussions of Russia’s influence in the Caucasus through the symbolism of man’s disregard for nature and its balance in the world. Hadji Murad himself exemplifies Tolstoy’s image of the highland peoples and their tragic relationship with Russia. One of the most significant tropes throughout the novella is that of the culturally displaced character, who either attempts to become integrated into an opposing culture or to integrate representatives of the opposing culture into his or her existing value structure. Charles King writes that

Hadji Murad, Tolstoy’s literary stand-in for highlanders in general, was precisely that: a deracinated native, a leader whose alternating loyalties mirrored the shifting fortunes of the Caucasian peoples and their variable relationship to Russian power. Their commitment to liberty in all its forms and meanings ended in tragedy. (King, 118)

Hadji Murad is provided with every opportunity to assimilate with Russian aristocratic culture. However, with each methodical stage of the attempted integration he disparages his Russian hosts’ way of life, either through polite comment or internal narrative. He cannot come to terms with accepting Russians’ help at the expense of relinquishing his cultural and religious traditions.

Tolstoy’s work also provides a prismatic array of framing narratives describing several viewpoints with different degrees of cultural perception. These narratives serve to support the theme of cultural barriers, but from a wide variety of perspectives. The narratives provide perspective from both cultures, respectively. From the Caucasian viewpoint, the reader is provided with the personal biography of Hadji Murad, the court proceedings of Imam Shamil, as well as the aftermath of the skirmish at Sado’s village. These snapshots give the reader a clear picture of the impact of Russian influence on the Caucasus. Comparatively, the Russian perspective is expressed through the death of Piotr Avdeev, his family’s reaction, and the letter of General Vorontsov to Chernyshov. There does not appear to be a strong sense of right and wrong portrayed in the story, only a conflict between two cultures that cannot seem to communicate (Weir, 210).

IV. Conclusion

The tragic outcome of interactions between the cultures of the Caucasus and Russia seems inexorable. In the works of these authors, the cultures exist in opposition to one another. The pervasive themes of war and tragic cultural misinterpretations, attributed in the works to both Russian and Caucasian values, create a barrier across which the characters cannot cross. However, these and other works helped foster among the Russian population a desire to test these barriers, based on the distinct, romanticized imagery of an untamed world on the edge of Russia (Layton 56). Through their works, Pushkin, Lermontov, Tolstoy, and many others crafted the very means by which Russians could attempt to interact with the Caucasus outside the scope of military confrontations.

The view of the Caucasus that emerges from Russian literature of the 19th century does not seem to adhere to Barrett’s middle ground theory of cultural relations. It appears that the perceived barriers inherent in 19th century Russian literature detailing the cultures of the Caucasus must be added as an integral element to the theory. Their impact on the Russian elite in their perceptions of what means they had to explore their national cultural identity and their relation to “uncivilized” nations of the “literary Caucasus” is quite evident. (Layton 90).

The barriers between both cultures shown in these works actually served to create a degree of intrigue, an enticing image of the cultural “other” that attracted the upper class of 19th century Russian society. Although the themes found in this literature often do not coincide with Barrett’s theory, they add an alternate path by which acculturation could slowly take place in the minds of the Russian readership. Through these vivid depictions of the traditions of both worlds, bridges were constructed to cross the cultural no-man’s land by encouraging greater interaction between two cultures, inspired by an air of mystery and challenge that extended outside the scope of Barrett’s original concepts.

Works Cited

Barrett, Thomas M. “Lines of Uncertainty: The Frontiers of the North Caucasus”. Slavic Review 1995. 23 pgs. Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies. Pittsburgh, PA.

King, Charles. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford University Press, 2008. Print

Langelben, Maria. “A Journey to Arzrum: The Structure and the Message”. 200 Years of Pushkin 2004. 20 pgs. Studies of Slavic Languages and Literature Publications. New York, NY.

Layton, Susan. Russian Literature and Empire: Conquest of the Caucasus from Pushkin to Tolstoy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994. Print

Lermontov, Mikhael Y. Bela. Фундаментальная Электронная Библиотека Русская Литература и Фольклор. Web July 1. 2002. Online.

—. Valerik. Фундаментальная Электронная Библиотека Русская Литература и Фольклор. Web July 1. 2002. Online.

Pushkin, Aleksander S.Кавказский Пленник. Русская Виртуальная Библиотека. Web 18 November. 2013. Online.

—. A Prisoner in the Caucasus, University of Washington Web Server. Web 18 November. 2013. Online.

Tolstoy, Leo N. Hadji Murad: Writings and Stories of Leo Tolstoy. Moscow: Эксмо, 2010. Print

Weir, Justin. Leo Tolstoy and the Alibi of Narrative. Yale University Press, 2011. Print