While Central Asia has a long, rich history, the modern nations of the region are a direct result of 20th century colonization. Prior to Soviet interference, the many ethnic groups and distinct societies of the region were loosely grouped under the geographic term of Turkestan.

Under Soviet control, the region was divided into the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic and Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in 1924. The Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic was created in 1929. In 1936, the Kyrgyz Socialist Soviet Republic and Kazakh Socialist Soviet Republic were delineated, creating the boundaries of the Central Asian states which exist today. Most of these states were carved out of the Russian SFSR, which originally covered nearly all the territory of the USSR and only gradually ceded territory to new entities which were then ruled by the regional branch of the centrally-controlled Communist Party of the USSR.

The five republics were intended to each house a unique society based upon the self-identification of major populations, but in some situations peoples were forced to align with an identity different from their own.1 Distinct tribes were forced to assimilate into larger groups, erasing their cultural heritage over time. Border lines were drawn in a manner which prioritized ease of ruling for the Soviets rather than the wishes of the population, leading to contentious decisions like the division of the fertile and strategic Fergana Valley.2

The Soviets practiced the policy of korenizatsiia— an intentional fostering of nationalism within each SSR— as part of their nation-building initiative. While the groups living in each SSR had long ago originated their own ethnic identities, for nomadic peoples like the Kyrgyz and the Kazakh, this was an introduction to the concept of national identity. Yet, even as the Soviets prompted their colonies to curate a sense of self in their new role as citizens, they also promoted an unfailing loyalty to the USSR, superseding their loyalty to their personal SSR.3 This sense of dual citizenship interfered with the true growth of national identity. Full sovereignty, and thus an uninhibited ability to mature their national identity, only came after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.4

Soviet Rule and Central Asian Art

The unique circumstances leading to the creation of the five Central Asian states complicates the study of this region’s artistic development. The influence of the Soviet Union can not be overstated—in many senses, Soviet policy reinvented visual art for these societies. Many of these groups had absolutely no tradition of easel painting, for instance, until the Soviets fostered that artistic growth. Yet, even while supporting artistic talent and educating artists in world-renowned schools, the Soviets also had strict policies limiting the possible styles and subjects that artists could depict. Now, post-independence, Central Asian artists are finally presented with the opportunity to define their own style of painting, free from Soviet censorship.

Many painters are choosing to express their national identity by incorporating local traditions of applied art and spreading awareness of previously suppressed local tragedies. However, no matter what lengths the artist goes to to make their work an expression of national identity, not an echo of Soviet identity, Moscow’s legacy is inescapable. Modern Central Asia’s art scene is suffused with a nearly tangible identity struggle. Art of Central Asia can only be understood fully if the observer is familiar with both the deeper societal history of the region and with the region’s Soviet past. To accurately interpret current Turkmen, Tajik, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Kazakh painting, one must first comprehend how painters arrived at this stage. For ease of understanding, the history of Central Asian art can be separated into three distinct periods—traditional, Soviet, and Post-Independence. By tracking the development of artistic motifs, techniques, and style, the cultural baggage and political nuance of painting in Central Asia is made clearer.

Traditional Art of Central Asia

The nomadic tradition of the Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, and Turkmen prohibited the maturation of the fine arts within these societies. While all held an appreciation for ornamentation, shown through embroidery, jewelry, feltworking, and woodworking, purely decorative items were rarely produced. Each of these peoples were renowned for their highly detailed, symbolic, and functional carpets. Ornamental rather than figural, carpet weavers used geometric patterns, saturated colors, and environmental motifs that were often also distinct signifiers of which tribe within their ethnicity that they belonged to.

The Kyrgyz in particular would make exceptionally decorative felt carpets to hang on the wall of their yurt opposite from the entrance. The matron of the house would design this carpet as a physical prayer—many of the common designs correlated to a wish for good fortune, health, or happiness and many come from the elements of the natural world, representing water and wind, for instance.

There are two main genres of Kyrgyz carpets: Ala-kiyiz and Shyrdaks.5 The former involves no stitching, only pressing wool to create one sturdy layer. The latter uses an applique technique, involving sewing a top layer of felt to a lower layer. Both layers have the same pattern, creating an effect of a piece with neither a foreground nor background, only one flat decorative plain.6

The Kazakh have similar traditions of hanging carpets, such as alasha. Weavers created these carpets using looms, traditionally decorating them with stripes and lines of white, blue, yellow, or brown.7

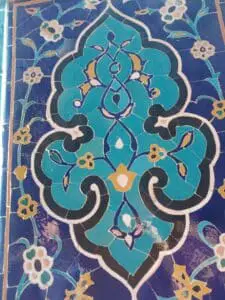

The more sedentary societies of the Uzbek and also had weaving among their prized arts, but also excelled in architecture as these settled societies built permanent cities. They created unique methods of decorating both the interiors and exteriors of their buildings. The influence of Islam after the 8th century prohibited figural representation, causing these societies to focus even more on highly detailed, pattern-based designs, particularly in ceramics and woodworking within these societies.8

Uzbekistan’s distinctive tiles, for instance, most commonly emphasize white, blue, and occasionally green, and brought beauty to the walls of mosques, madrassas, minarets, and palaces across historic Uzbekistan. These colors, now used in the flag of Uzbekistan, are highly symbolic. White represents spiritual purity and peace while blue relates back to the spiritualism of both Zoroastrianism and Islam. The Tajik matured many wood-working techniques, including flat cutting, deep cutting, double-sided cutting, cladding, and relief cutting. Relief cutting was often used to carve intricate designs into the pillars of mosques. Commonly, these designs included geometric motifs like circles and curvilinear shapes.9

Soviet-Era Art of Central Asia

As an extension of the Cultural Revolution, in 1923 at the 12th Party Congress Joseph Stalin redefined the Communist Party’s “Nationalities Policy.” During the conference, Stalin claimed that in order to combat Russian-chauvinism—a force opposing the egalitarian ideals of communism—minority groups across the USSR needed to grow a stronger sense of identity and recognizable culture. New policies were instituted to encourage education, literacy, and the arts in the many republics of the USSR. Educational clubs were created across the Soviet Union. In the nomadic regions of Central Asia, the mission of these institutions was to “civilize” and “bring cultural enlightenment” to the local population. Although the Party’s official stance was staunchly against the concept of Russification, these clubs were meant to spread Western ideas of fine art and literature.10

In Kyrgyzstan, these clubs were given the name “Red Yurts.” Starting from a modest collection of a few dozen locations, this effort proved successful and was expanded to nearly 600 locations by the mid 1940s. These educational clubs multiplied in other Central Asian republics as well. In all locations, those who attended these clubs who showed talent for the arts were given the opportunity to study in major educational institutions in places like Moscow or St. Petersburg. Such artists returned home having been exposed to the fine European-style art which filled Russian museums. Ideally— according to the Soviet plan—, these artists would then combine the technical skills gleaned from their Russian education with staunch communist ideology and recognizable local symbols. The resulting works, created by a member of the local community, would appeal to the people of the republics much more so than similar works produced by Russian artists.

After returning home, these artists would be inducted into their republic’s artists’ union. All of these unions were branches of the Artists’ Union of the USSR, which was founded in 1932 as an updated version of the Union of Soviet Artists. Members enjoyed benefits and prestige; the union provided salaries, public commissions, studio space, and exhibition opportunities.11 However, any works that these artists produced had to conform to the Socialist Realist style. This meant that all art needed to be created in a realist style and had to convey a socialist moral. The impact of such strict political regulations may have had a lasting effect on artists, causing art produced in Central Asia to be more politically motivated than art produced in other regions.

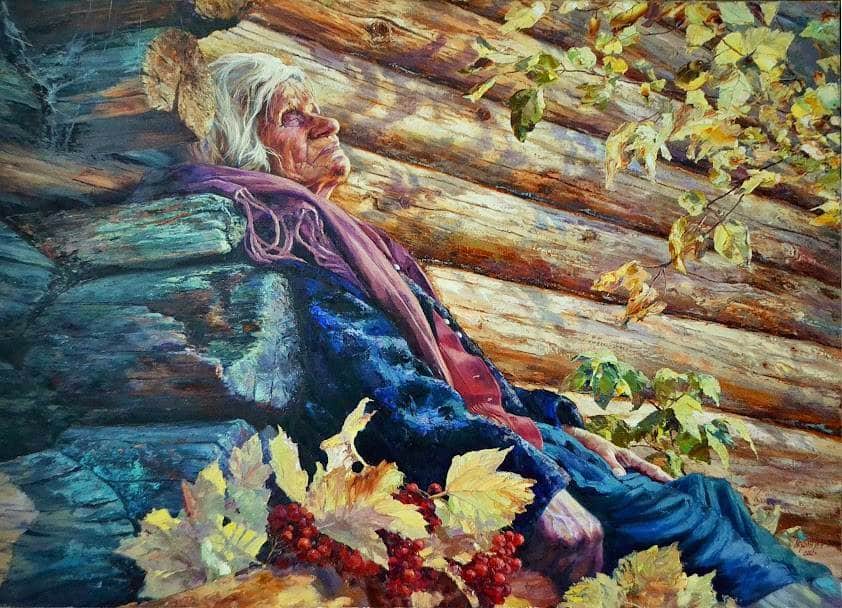

Though many think of Socialist Realism as merely depictions of Soviet leaders or images of laborers, there are also portraits, still lifes, and landscapes which fit the definition and passed censorship. The works of Durdy Bayramov, an artist born in Soviet Turkmenistan, are an excellent example. This prolific artist mainly created still lifes, landscapes, and scenes representative of everyday life in Turkmenistan. For his exemplary work, he received the title of People’s Artist.

Nikolai Karakhan, an artist working in the Uzbek SSR, was an example of a more avant garde artist who still worked in the Socialist Realist mode. His paintings showed farmers, builders, cotton-pickers, and other such “heroes” of the Soviet era, yet he portrayed them in a style less realistic than many of his Soviet contemporaries. The saturated colors and bright tones common in his work recall the French fauvists, while the sense of naivety from his blurred backgrounds and simplified shapes makes his work stylistically more similar to that of the post-impressionists rather than the Soviets. He, like Bayramov, was awarded the title of People’s Artist.

Semyon Chuikov, the most influential Soviet-era Kyrgyz artist, and debatably the most important Kyrgyz artist of any period, not only earned the title of People’s Artist of the Kyrgyz SSR, but People’s Artist of the USSR.12 Although many of his works achieved great renown, his most famous work is Daughter of Soviet Kyrgyzstan (1950), which uses the common Soviet motif of personifying the republics as young women. This was often seen as advancing the idea that the republics were vulnerable and in need of guidance, yet exhibited great potential. However, in Daughter of Soviet Kyrgyzstan, Chuikov’s young girl peers into the future so shrewdly and with such determination that, rather than communicating that she needs the help of intervening Russians, it is clear that she is capable of bettering herself through her own hard work. This inspirational message resonated with the Kyrgyz in 1950 and still does today.

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Named After Gapar Aitiev serves as a microcosm of the fine art world in Kyrgyzstan. Opened in 1935, it was the first fine art gallery to be opened in the country and was a product of the Soviet initiative to foster cultural pride and a sense of identity in the Kyrgyz SSR. The museum began as a collection of art acquired from the Hermitage, consisting of Russian and Western-European paintings and sculpture. As more and more Kyrgyz joined artist unions and began producing “approved” works, the museum transitioned into exhibiting mainly Kyrgyz Socialist Realist artworks.

Similarly, the Museum of Arts of Uzbekistan, also founded in 1935, initially showcased Western-European and Russian fine art before gradually acquiring a collection of works by Soviet Uzbek artists. Both the Uzbek and Kyrgyz museums were funded by Moscow and were yet another instance of the top-down effort to simultaneously encourage artistic accomplishment and to seize control over the means of disseminating art.13

Post-Independence Era Art of Central Asia

With the Soviet Union’s fall, the Union of Artists of the USSR also came to an end. This institution had been solely responsible for the production, consumption, and circulation of art in all republics, and without this guiding center, each republic’s union was now forced to either operate independently or to cease.14 While this was a source of chaos in artistic communities, it was also an opportunity for change as it represented the opportunity for full national autonomy and artistic freedom.

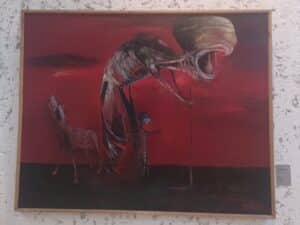

At this early stage in each country’s history it was essential to document current attitudes, ideas, and values for future generations to understand the conditions of the nations’ inceptions. As well as recording such knowledge for posterity, it was also crucial that such thoughts be disseminated internationally to foster empathy and facilitate a deeper level of intercultural communication and understanding, particularly as the former soviet republics redefined themselves and carved out a niche for themselves in the global space. Further, without Soviet censorship, sensitive episodes of the nations’ past could finally be discussed and digested through art. The younger generation could feel connected to the tragedies of their peoples’ past through these expressive, heartfelt works.

While the art scenes within these countries are highly diverse, in the interests of giving a fast overview of what is being produced there, we can present a single artist whose works can be considered well known and influential.

An artist who embraced both new styles and new themes is Kyrgyz artist K. J. Bekov. In two of his oil paintings, Migration and The Outcast, Bekov uses a highly expressive style to tell the story of the 1916 Urkun—the Kyrgyz exodus to China to escape conscription by the corrupt Tsarist-Russian government. This traumatic event scarred the people of Kyrgyzstan and has had a lasting effect both politically and culturally on the region. This topic was strictly banned under Soviet censorship, as it had the potential to set the Kyrgyz and Russian populations against each other.

Although Kyrgyzstan has been considered a beacon of democracy in Central Asia, it is not entirely free the political repression of art. In 2019, an incident occurred after the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts displayed an exhibition called Feminnale. This collection of feminist works depicted themes challenging gender norms and questioning economic disparity between the sexes. Once this exhibition went public, outrage was immediate. Critics called the exhibition “perverted” and “amoral,” and several pieces were removed from the public eye by Kyrgyz Minister of Culture Azamat Zhamankulov. Members of parliament publicly opposed the exhibition and the museum director Mira Dzhangaracheva resigned after an onslaught of threats following the publicity.

The life of contemporary Turkmen artists is complicated. The government has made efforts to tightly control artistic expression within the country and has instituted isolationist policies. This prevents the works of many Turkmen artists from being shown abroad and, likewise, means that some of the best-known Turkmen artists are those who now live and work outside of Turkmenistan. For example, Amir Kerr, an artist born in Turkmenistan who later relocated to Poland, draws on pop culture and surrealism in his paintings. Although his work could be described as derivative, he claims to present the reality of art and culture in a post-modern world.

In Kazakhstan, Kairbay Zakirov is a commercially successful painter. Spanning the gap between Soviet artists and post-independence artists, Zakirov was a member of the Kazakh Union of Artists, and still is now. The Kazakh branch of the Artists’ Union survived the collapse of the USSR and continues to shape national art production and circulation. However, Socialist Realism is no longer enforced and, Zakirov, inspired by the “heroic past of the Kazakh people,” uses a semi-abstract, post-impressionist style to convey the spirituality of the nomadic Kazakh past.16

Farrukh Negmatzade—a contemporary Tajik artist—like Zakirov, was a well-known artist during the Soviet period. He now strives to capture the simplicity of traditional life and the slow pace and honesty of the Tajik countryside through landscapes, portraits, and depictions of ordinary situations. He seeks his artistic materials and inspiration from bazaars, mosques, and small villages, although he himself is from Dushanbe — the largest Tajik city. Not nostalgic for the industrialization of the Soviet era, but for the rural lifestyle of traditional Tajik culture, Negmatzade’s uncomplicated style and paintings celebrate Tajik national identity as he perceives it.

Yet, despite the many benefits of creative expression, there is one major drawback of total independence from the Soviet Union: a sudden lack of funding. Taking the Gapar Aitiev Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts as an example, this previously grand building, built in the then cutting-edge style of socialist modernism, has fallen into disrepair after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, as evidenced by the water-damaged and uneven flooring. Post-independence, Kyrgyzstan, like all other former republics, has more pressing matters than the upkeep of the arts as they strive to also maintain infrastructure, support business, develop education, and more, often on the basis of a weak economy and underfunded tax base.

Conclusion

As this region underwent major upheavals, transitioning from Turkestan to Soviet Turkestan, to Soviet Central Asia, to independent Central Asia, artists were forced to adapt. First encouraged in the 1920s to shift from applied arts to painting and sculpture, then instructed on precise styles

and themes to emulate in the 1930s, artists either had to conform to Soviet guidelines or risk falling into obscurity, or worse, being punished. As different leaders took charge of the USSR, official regulations shifted, sometimes loosening, sometimes tightening, but no matter how quiet, there was always a voice in Moscow controlling artistic output. Then, in 1991, as each Central Asian republic declared sovereignty, Central Asian states found itself with a classically educated community of artists to manage fully independently. Some semblance of policing is maintained in most states, but artists also continue to persevere in creating art and most of the region is moving in a positive direction to allow freedom of expression. Although many of the most well-known artists working in Central Asia now worked under both the Soviet and independent systems and many received training in Russian art schools, a majority of these artists have embraced their newfound freedom to experiment with a multitude of styles and subjects and often to bring their art closer to their own ethnic expressions. Although Central Asian painting owes its birth to Soviet policy, and although artists’ technical skills may have originated through Russian instruction, artists are finding ways to speak true to the experience of their culture.

Footnotes

1 Francesc Serra Massansalvador, “The Process of Nation Building in Central Asia and its Relationship to Russia’s Regional Influence”, Vol. 10 No. 5, June 2010: Published with the support of the EU Commission.

2 “The Tajiks of Uzbekistan,” Taylor & Francis, accessed November 30, 2022, Online.

3 Francesc Serra Massansalvador, “The Process of Nation Building in Central Asia and its Relationship to Russia’s Regional Influence”, Vol. 10 No. 5, June 2010: Published with the support of the EU Commission.

4 Steven Sabol (1995) The creation of Soviet Central Asia: The 1924 national delimitation, Central Asian Survey, 14:2, 225-241, DOI: 10.1080/02634939508400901

5 “Arts and Crafts in Kyrgyzstan.” Информационное Агентство Кабар, Online.

6 “Kyrgyzstan Culture,” Advantour, accessed November 30, 2022, Online.

7 Committee of Tourism Industry of the Ministry of Tourism and Sport of the R of K :: Home, accessed November 30, 2022, Online.

8 “Arts & Crafts.” Arts & Crafts in Tajikistan, Online.

9 Voice of Central Asia. Online.

10 “Accessible Art and Dialectic Potential: The Soviet Legacy in the Art Community of Kyrgyzstan,” Museum Studies Abroad, April 15, 2021, Online.

11 IĞMEN, ALI. “The Making of Soviet Culture in Kyrgyzstan during the 1920s and 1930s.” In Speaking Soviet with an Accent: Culture and Power in Kyrgyzstan, 22–36. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012. Online.

12 “Semyon Chuikov, Founder of Kyrgyz Painting,” Museum Studies Abroad, April 15, 2021, Online.

13 “Arts & Crafts.” Arts & Crafts in Tajikistan, Online.

14 Okada, Kochi. “Re-Legitimising Painting in Tashkent, Uzbekistan After the Fall of the Soviet-Union (1991-2004).

15 “Artist: Amir Kerr.” Amirkerrart. Accessed January 4, 2023. Online.

16 Kazakh Artists’ Exhibition. Online.

Bibliography

“6 Exhibitions by Cyprus Museum of Modern Arts at a Time… 4 Solo Painting Exhibitions and Art Exhibitions of Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan Artists to Be Opened by Minister of Economy and Energy Hasan Taçoy…” Near East University I neu.edu.tr, July 15, 2019. Online.

“Accessible Art and Dialectic Potential: The Soviet Legacy in the Art Community of Kyrgyzstan.” Museum Studies Abroad, April 15, 2021. Online

Aigerim Turgunbaeva, Tatyana Zelenskaya. “Mightier than the Sword: The Political Artist Capturing Rage and Resistance in Kyrgyzstan.” The Calvert Journal. Online.

“Artist: Amir Kerr.” Amirkerrart. Accessed January 4, 2023. Online.

“Arts & Crafts.” Arts & Crafts in Kazakhstan. Online .

“Arts & Crafts.” Arts & Crafts in Tajikistan. Online.

“Arts and Crafts in Kyrgyzstan.” Информационное Агентство Кабар. Online.

“Ashgabat to Host First-Ever Contemporary Art Exhibition in Turkmenistan.” News Central Asia (NCa), 25 Oct. 2022. Online.

“Byashim Nurali – an Artist from the People.” Turkmenistan Altyn Asyr, 8 Nov. 2022. Online.

“Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent, CCA Tashkent.” www.ccat.uz . Committee of Tourism Industry of the Ministry of Tourism and Sport of the R of K : Home. Accessed November 30, 2022. Online.

“Emil Kasymov: Contemporary Kyrgyz Painter, Sculptor.” SINGULART. Online.

Goff, Samuel. “Shtab: The Queer Communists of Bishkek Bringing Politics and Art Back Together.” The Calvert Journal. Online.

“How Contemporary Art Is Developing in Kazakhstan?” Қазақстан туралы жаңалықтар – Еl.kz, February 21, 2022. Online.

“‘Kazakhstan Artists Exhibition’ Consisting of 50 Artworks of 12 Artists from Kazakhstan and Solo Print Painting Exhibition of Kazakh Artist Kairbay Zakirov Consisting of 45 Print Paintings to Be Opened by Minister of Economy and Energy Hasan Taçoy…” Near East University, July 1, 2019. Online.

“Kyrgyzstan Culture.” Advantour. Accessed November 30, 2022. Online.

“The Not-Naive Naivety Arts of Tajikistan.” Voices On Cental Asia, 18 Feb. 2021. Online.

Okada, Kochi. “Re-Legitimising Painting in Tashkent, Uzbekistan After the Fall of the Soviet-Union (1991-2004).”

“The Power and Depth of Contemporary Art Is in the Origins.” Turkmenistan Altyn Asyr, 9 Nov. 2022. Online. Premiyak, Liza.

“Kyrgyzstan: A Photographer Documents a Quiet Nation Waking up to a New Dawn.” The Calvert Journal. Online.

“Semyon Chuikov, Founder of Kyrgyz Painting.” Museum Studies Abroad, April 15, 2021. Online.

Shkurpela, Dasha. “Aida Sulova: Bishkek’s Pioneering Art Impresario.” The Calvert Journal. Online.

“Soviet Kazakh artist Abylkhan Kasteyev 1904-1973”. “Traditional Turkmen Carpet Making Art in Turkmenistan.” UNESCO. Online.

“The Tajiks of Uzbekistan.” Taylor & Francis. Accessed November 30, 2022. Online.

“‘Turkmenistan Culture, Art and Photography Exhibition’ Opened at the National Library in Ankara.: News.” Türk Devletleri Teşkilatı. Online.

“ВЫСТАВКИ И СОБЫТИЯ.” MuseumKnmii. Online.

Oʻzbekiston Davlat Sa‘nat Muzeyi. Online