It has been said that Gogol’s career was like that of a meteor. It appears suddenly, burns brightly, fades quickly, and with its impact, changes the surrounding landscape and environment forever.[1] It is interesting that Gogol’s greatest play, The Government Inspector, was described with a similar power-type metaphor. Nabokov wrote, “(it) begins with a blinding flash of lightning and ends in a thunderclap… it is wholly placed in the tense gap between the flash and the crash.”[2] To add another, The Government Inspector builds speed from its very beginning. By its end, the frenetic pace bursts off the stage and crashes through the theater walls. The audience departs through the wound.

The purpose of this paper will be to understand The Government Inspector, the forms of its text and presentations, the impact each had upon their audiences, and, of course, the man who wrote it.

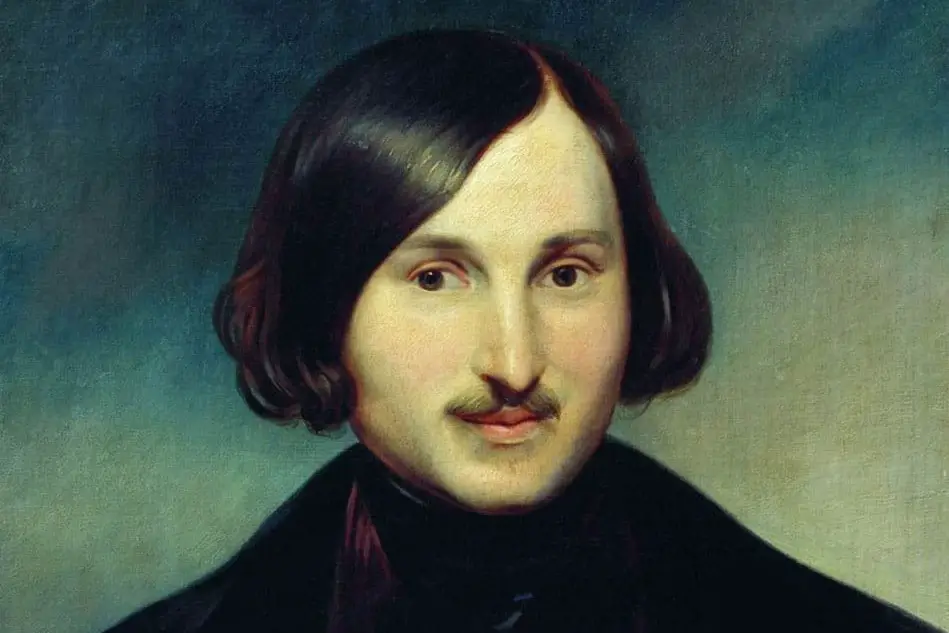

Let us begin with the author. Nikolay Vasilievich Gogol was born in Sorochintsi, just outside Poltava, Ukraine in 1809. His affluent family held a position in the Cossack nobility. His father was well educated: an amateur playwright, poet, and “gentleman farmer” who raised his son in relative indulgence.[3] Except for this, not much is known about Gogol’s early childhood. However, we can discern much about Gogol’s primal mindset from the culture he was raised in.

The Ukrainian Cossacks are a proud and powerful ethnic group. In 1654, they allied with the Russians to drive the Poles from the Left-Bank Ukraine and Smolensk. The ensuing victory not only enlarged Ukraine and provided Russia with a valuable land route to Europe; it also marked the beginning of a prosperous, however unstable, relationship between Cossacks and Russians. With Cossack assistance, Russia went on to further expansion and military success against the Poles, Swedes, and Turks. However, Russia’s attempts to forge the Cossacks into Russia’s consolidating government were met with strong resistance. In the Third and Fourth Peasant Wars, Cossacks in the Don and Volga River region (just a short distance from Poltava) led other dissident groups to revolt in 1707 and 1773. The Cossacks, like most Russians, blamed oppression on corrupt officials, while considering the Tsar essentially infallible.[4] In fact, Emelian Pugachev, leader of the Third Peasant War, gained a wide following by claiming to be the deceased Tsar Peter the Third.

This pride of heritage and tempered dissidence was to provide most of Gogol’s literary topics. His earliest successes, “Dikinka tales” (1831), Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka (1831-2), and Taras Bulba (1835) concern Ukrainian life and culture. Furthermore, as we shall see, The Government Inspector is a striking appeal for reform.

At age ten, Gogol began a formal education, eventually graduating from the School of Higher Studies at Nezhin in 1828. There he pursued interests in theater (originally in directing and acting) and in classical studies.[5] Afterwards, Gogol settled in St. Petersburg where he failed at several government posts and continued pursuing the theater. He attended varied productions in St. Petersburg including vaudeville,[6] neoclassicist plays, (ranging from Sumarokov’s early tragedies to adaptations and translations of French and German plays),[7] and the new Sentimental dramas. Gogol would blend all these influences: classical studies and various theater genres, into his distinctive and often misunderstood dramatic form. After his first literary successes, published by his friend, Alexander Pushkin, Gogol became a full-time writer in 1835.

Experimentation in form was not new to Russian writers. Although folk theater and performance had existed for centuries, Western style drama was unheard of in Russia until about 1650,[8] when French plays were imported along the new trade routes. Peter the Great’s westernization of Russia in the mid-1700’s hastened Russian language drama, largely modeled on Cornielle and Moliere. Catherine the Great’s drive to bring culture and enlightenment to Russia hastened its popularity. Both rulers saw great potential in the new drama to teach and entertain the masses. They hoped to use it to forge an enlightened (and docile) populace. Russian authors, operating from neoclassicism rather than Machiavellianism, also sought a drama that would teach and entertain, with the emphasis on pedagogy. As Alexander Sumarokov wrote: “Comedy’s nature is to correct manners through ridicule. / Its rule – to amuse and serve.”[9]

With the turn of the century, two interrelated ideas were introduced to Russia: Nationalism and Romanticism. Romanticism helped steer Russian authors away from strict adherence to neoclassical ideals. The new direction was solidified as Nationalism demanded Russia fervently seek national forms of art, including a national theater. Gogol wrote passionately against the production of foreign plays (they were essentially meaningless to Russian audiences and actors, he felt) and added: “for heaven’s sake, give us Russian characters, give us ourselves!”[10] Russian language Western drama, still in relative infancy at just over a century old, was forced to mature quickly.

Despite its tender years, Russian drama realized one of its finest fruitions very quickly. In 1836, Gogol finished The Government Inspector. Milton Ehre states:

The wide social spectrum of that play, the recognizable “Russianness” of its characters, its richly colloquial language the likes of which had never before been heard on the Russian stage caused it to be hailed as a realization of the dream of a national theater.

However, the genius of Gogol’s play lies in much more than the play’s national style, for many troupes of many nationalities have performed The Government Inspector to many appreciative audiences of many nationalities.[11]

Gogol’s true genius lies in his play’s form. As previously mentioned, Gogol blends neoclassicism with various other dramatic genres, as well as a comic blend of illogicality and logic. Also previously mentioned, the play and its form may best be understood in terms of speed and power. Gogol has streamlined his play with neoclassical devices. His characters are familiar to us from tradition. Khlestakov is a comic braggart, Osip, a wily servant, Marya, a naive ingénue. Also, his plot turns on the classical case of mistaken identity.[12] The Government Inspector closely follows the unity of action, giving it, despite its colloquial language and social spectrum, elegance and simplicity. However, because neoclassical forms were under attack, as well as because of Gogol’s own creative impulses, he only adhered to the form so long as it was useful to him.[13] For example, the unities of time and place are observed only loosely; the twenty-four-odd hours of the play are stretched over the course of two days; the action takes place in varied locations, but all in one small provincial town. Horace’s utile and dulce are certainly present, but Gogol blends the utile into the dulce, relying on the play’s comic absurdity and a few unique stylistic devices, such as an “inverted catharsis,” rather than pure didacticism. We will discuss this later.

Gogol openly despised vaudeville, “this facile, insipid plaything (that) could only originate among the French, a nation lacking a profound and fixed character,”[14] as he called it. However, Gogol also possessed a great respect for vaudeville, just as he possessed a great respect for the French. “O Moliere, great Moliere, you who developed your characters in such breadth and fullness and traced their every shadow with profundity,”[15] Gogol laments in the very paragraph following his French-bashing. While the French lacked profundity of character, Moliere possessed profundity in apparent abundance. While vaudeville was “facile, insipid,” it possessed a briskness of pace, actability, and a novelty that carried across political and class lines.[16]

Gogol adopted these qualities to give speed and power to his streamlined play. Previous comic playwrights relied on the heavy use of a raisonneur to express the utile of their plays. In Fonvizin’s The Minor, for instance, fully one-fifth of the text is given over to Starodum’s long speeches on morality. While this tended to make the play’s moral lesson abundantly clear, it also slowed the comic pace, creating “dead air” for both actors and audience. Gogol’s solution to this was ingenious and radical: complete elimination of the raisonneur. In doing so, of course, he completely eliminated a stable center for his play. To again quote Milton Ehre: “(Gogol’s) great innovation… was to write a comedy without any ballast of sanity.”[17] The Government Inspector spins nearly out of control, with hapless, self-serving, amoral characters running in farcical situations that beg physical comedy (such as Khlestakov’s dual and simultaneous seduction of the mayor’s wife and daughter, his solicitation of bribes from several officials in the course of just a few minutes, etc.). On the verge of chaos, The Government Inspector is vaudeville, but remains, somehow obviously, a moral drama.

As stated before, Gogol’s characters are amoral, not immoral. A government inspector means a possible threat to their posts; therefore, they bribe the perceived threat to neutralize it. There is no intrigue, no premeditated scheme to do wrong, merely a practical system that is followed. As Gogol states: “My heroes are not all villains; were I to add but one good trait to any of them, the reader would be reconciled to all of them.”[18] Gogol’s characters are grotesque, but not completely without hope. It is precisely this hope, this possibility of salvation that allows the play to be open to morality.

The morality is communicated through Gogol’s dialectic, inherent in his major stylistic devices. In his “The Denouement of The Government Inspector,” a short piece written shortly after its namesake, Gogol has “First Comic Actor” give the audience the “key” to understanding The Government Inspector.

Take a close look at the town depicted in the play. Everyone agrees that no such town exists in all of Russia; a town where all the officials are monsters is unheard of. You can always find two or three who are honest, but here – not one. In a word, there is no such town. [19]

Gogol expected his audience to realize they were watching a narrative hyperbole, a world turned on its head, and instinctively perform the intellectual gymnastics to right it.

Let us not swell with indication if some infuriated mayor or, more correctly, the devil himself whispers: “What are you laughing at? Laugh at yourselves!” Proudly we shall answer him: “Yes we are laughing at ourselves, because we sense our noble Russian heritage, because we hear a command from on high to be better than others!” Countrymen! Russian blood flows in my veins, as in yours. Behold: I’m weeping.[20]

Gogol expected his comedy without sanity, his world without logic or morals to create a hunger in his audience for sanity, logic, and morals via a sort of Platonic dialectic. Platonic logic, as S. Fusso and P. Meyer point out, permeates all of Gogol’s works.[21]

Another of Gogol’s stylistic devices further aids the speed and flow of the play. As stated earlier from Nabokov, The Government Inspector “begins with a blinding flash of lightning and ends in a thunderclap… it is wholly placed in the tense gap between the flash and the crash.”[22] The reason this observation rings true is because Gogol has completely omitted any falling action and the denouement and has condensed the exposition into near similar oblivion.

The Mayor’s first two lines let us know all we need; “Gentlemen! I’ve summoned you here because of some very distressing news. A government inspector is on his way.” is followed by “From St. Petersburg, incognito! And with secret instructions to boot!”[23] We know now the action of the play turns on a government inspection. We know that no one knows who the inspector is. Any audience member with even brief experience classic plots will know that the comic action will turn on mistaken identity. Finally, we know from “Gentlemen,” the concerned and indignant tone of the announcement, and the brief explicatives of concern uttered by the other characters, that they are likely provincial officials. Provincial officials are the only people who would show concern for this; they are the only people who may lose their positions from such an inspection. Hence, the exposition is taken care of in less than a quarter page. Other needed information is introduced as part of the rising action.

Gogol spends the next three and half acts building a rising action. Khlestakov arrives on the scene, is mistaken for the inspector, and is given a royal treatment he does not understand, but takes full advantage of. Minor characters are introduced and a potential love affair between Khlestakov and the mayor’s daughter (and possibly wife too) is developed. The climax begins near the end of act four, with the famous “bribe scene,” where a rapid and farcical procession of officials commit continuous bribery. However, this climax never ends, but continues through the fifth act, reinvigorated by the arrival of the Storekeepers, the reading of the letter, and given one final boost with the last line of the play: “the government inspector has arrived.”[24] As all characters freeze on stage, the pace has nowhere to go but crashing through the theater walls.

The result of Gogol’s stylized dramatic structure is the final stylistic device we will discuss, a device whose intent seems to have backfired on Gogol. This device can only be called an “inverted catharsis.” The play certainly possesses catharsis: it creates joy for the audience and purges them with laughter. However, other emotions, such as the anger at seeing such corruption as well as the frustration at wanting to right Gogol’s upside-down-world and not seeing it happen, are given no release. The audience must exit through a gaping wound created by the exiting action, with these emotions seething within them, desiring release; this is inverted catharsis.

It is possible that Gogol intend this, assuming the post-production release of this emotion would be channeled into improving society and stamping out corruption. However, more often than not, the audience simply directed their anger and frustration at the play and/or its author. Gogol complained about this:

“He’s an incendiary! A rebel!” And who is saying this? Government officials, experienced people who ought to know better… and this ignorance is widespread. Call a crook a crook, and they consider it an undermining of the state apparatus… Consider the plight of the poor author who nevertheless loves his country and his countrymen intensely.[25]

Gogol is frustrated but uses the opportunity to point out the fact that this reaction proves the need for change in his beloved Russia.

It goes without saying, then, that the original production of The Government Inspector was not generally well received. In addition to the adverse emotional reaction, there is an artistic theory for the poor reception. This theory is presented by Milton Ehre and supported by another historian of the Russian stage, Anatoly Altschuller.

Before we discuss this theory, however, we should discuss why this play, seen as “undermining of the state apparatus,” was allowed to remain on the stage throughout the reign of Nicholas I, a tsar infamous for oppressive censorship. The tsar himself was present at opening night, which meant that all important officials and nobles were there as well,[26] and upon leaving the tsar was heard to say “All have gotten their due and me most of all!”[27] The tsar’s quote requires some explanation. First, it should be pointed out that in the play, much like in a Cossack rebellion, the tsar is never slandered, only officials. Second, it should be noted that every tsar since Alexi had tinkered with reforming the role and position of provincial officials. Milton Ehre adds: “We may guess that Nicholas I, who had little confidence in his subordinates, consented in order to have an opportunity to see them squirm.”[28] Finally, it should be noted that the only time a direct representative of the tsar appears it is in the capacity to change the province’s government and to hold it accountable to corruption. Gogol’s own interpretation of the final scene does nothing to hinder the good position of the tsar either:

I vow, our spiritual city is worth the same thought a good ruler gives to his realm. As he banishes corrupt officials from his land sternly and with dignity, let us banish corruption from our souls![29]

The “due” the tsar has received is a favorable comparison with almighty God, everyone else, with damnable sin. Obviously, the tsar had little problem with this.

With Gogol safely past the censors, we return to a discussion of why the original production failed. Erhe claims that the actors tried to perform The Government Inspector as “harmless vaudeville,”[30] hence detracting from Gogol’s vision of a socially corrective play. A vaudeville presentation would have also detracted from its “Russianess,” as vaudeville was seen as French. Gogol backs Ehre’s theory:

My creation struck me as not at all mine… (Khlestakov) turned into someone from the ranks of those vaudeville rogues… in general, (the characters) were so affected that it was simply unbearable. [31]

We can certainly see how this would detract from the redemptive value of the final scene:

The curtain fell at a confused moment and the play seemed unfinished. But I’m not to blame. They didn’t want to listen to me. I’ll say it again: the final scene will not meet with success until they grasp that it is a dumb scene.[32]

Gogol saw reliance on farce as detracting from the dialectical satire and overall message.

Anatoly Altschuller in A History of the Russian Theater provides evidence to back Ehre’s theory of why the original production failed. He states that the 1830’s were a time of transition for Russian theater. A night at the theater was a variety experience. The same actors might present all vaudeville, dance, song, tragedy, and comedy in the same evening.[33] Nikolay Osipovich Dyur, who played the original Khlestakov, and who Gogol thought helped turn the production away from his vision, was widely loved as a vaudeville performer. Altshuller also points out that Dyur’s strength was “his personality, not his acting skills.”[34] Alexsandr Martynov, who played Bobchinsky and whom Gogol criticized as “hopelessly affected” was popular for his portrayal of low comic characters.[35] Varvara Asenkova, who played Marya, was primarily famed for “travesty” parts on the vaudeville stage.[36] Overall, choices of costuming and staging were decidedly vaudeville.[37]

All this shows the original production of The Government Inspector deviated from Gogol’s vision of it. But it was not a complete failure. In Gogol’s own words:

The reaction to (The Government Inspector) has been extensive and tumultuous. Everybody is against me. Respected officials, middle-aged men, scream that I hold nothing sacred in having had the effrontery to speak of officialdom as I did. The police are against me, the merchants are against me, the literati are against me. They rail at me and run off to the play; it’s impossible to get tickets.[38]

While many were offended by the content and style of the presentation, everyone was excited and talking. Many, such has Herzen, a contemporary drama critic, saw the play as “contemporary Russia’s terrible confession” and demanded radical social and political change.[39] Others argued that Gogol’s text is essentially conservative, asking only for the present system to work properly.[40] Some sided with Gogol in decrying the inappropriate presentation of the text. Others argued that it had appropriately brought out the play’s humor. Victor Borovsky, a Russian and a respected modern theater historian and theorist, still insists humor is the play’s most important quality.[41]

However, if we regard only Gogol’s intent to encourage his audience to seek redemption or beauty or perfection, this “artistic failure” turns out to be quite an achievement. The unexpected thing was that people sought in so many different ways, in so many different places. Some sought redemption and beauty in dramatic form. Turgenev, the famous Russian playwright and critic, uses the date of The Government Inspector’s premier to mark the beginning of a new age for Russian drama: “Ten years have passed since The Government Inspector was first performed. A wonderful change has come about since then in our ideas and in our demands.”[42] Altshuller adds: “by the end of (ten years) realism, the ‘natural school,’ was predominant.”[43] Many of Gogol’s chastised actors moved away from vaudeville and romanticism to realism, and became some of Russia’s greatest actors and actresses ever.[44] Martynov, Gogol’s chastised Bobchinsky, became the “first true Khlestakov” after his conversion. The premier of The Government Inspector left much to be desired aesthetically, but its ideological impact was great; it instigated the dramatic realism Russia would someday be famed for.

One could also argue that the political implications of this first run were also great. Major revolts occurred in the 1860s, just a few years after the premier of The Government Inspector. Although these revolts amounted to naught, perhaps they were partially fueled by the discourse and controversy created by the play.

Over seventy years later, Stanislavski would also find redemption in The Government Inspector. It was during the rehearsals for a new production that, in 1908, he fully realized his directorial style. At the start, Stanislavski was tyrannical, ordering his actors to act in particular manner, with particular motion. In his own words:

I began to order the actors about exactly as I ordered about amateurs. Of course they did not like it, but they obeyed, for they lost all ground beneath their feet. What I said and what I wanted was right. I saw the truth of that in the following years in many productions of (The Government Inspector). But the means I used for attaining my new ideas and influencing the actors were not the right ones. Simple despotism does not persuade an actor to his inner self; it only violates his inner self.[45]

Stanislavski thus began to solidify his theory of method acting. He began direct from a more psychological standpoint. He developed a terminology extrapolated from his readings of Gogol. These early terms, such as “nail” and “circle” eventually became the terms we know today as “through-line of action” and “circles of concentration.”[46]

Despite the inspiration Stanislavski received from Gogol and The Government Inspector, his presentation of the play did not create lasting fame for him. Although it favorably reviewed during its time, praised for its “enriched realism,”[47] although it was essentially an “enriched realism” Gogol wanted his play presented with, this production has not been remembered as a masterpiece. Perhaps this is because Stanislavski’s technique was still in its infancy. In any case, Stanislavski’s production had no significant impact on society or art, despite the revolutionary impact of Stanislavski’s new theories and techniques of acting, partially extrapolated and inspired by Gogol.

Of more interest to us here is the advent of a very different technique brought to full fruition in the presentation of Gogol’s play by one of Stanislavski’s contemporaries. While Stanislavski’s inspiration is interesting, the rest of our discussion will concern Vsevolod Meyerhold and his 1926 masterpiece production of The Government Inspector.

Simply simply saying he rejected realism and naturalism can best sum Meyerhold’s theories and techniques. Although Meyerhold did not fully systemize his theory, he did leave a lengthy discussion of them in his book Meyerhold on Theater. From this, we can tell much about his approach to The Government Inspector.

He considered a quote from Gogol most important in interpreting the script: “I decided to hold up everything to ridicule at once.”[48] Therefore, Meyerhold decided: “The Theater was faced with the task of making The Government Inspector an accusatory production… (of) the entire Nicholayan era, together with the way of life of its nobility and officials.”[49] To accomplish this, he emphasized the grotesque elements of the play. At once it was seen as realistic, and seen through a bent lens of hyperbole and fantasy. The effect was nightmarish, a memory something one would never want to return to.

Meyerhold essentially rewrote Gogol’s script. He broke it into fifteen episodes, which were “ideally suited to the disorientating effects of the grotesque.”[50] He also added additional elements from Gogol, references to Dead Souls and other plays and added additional characters, a laughing charwoman, for instance, to add mood and probably additional disorientation.[51]

If we look at one of the surviving photographs of the play (copyrighted photo available in Meyerhold on Theater, Hill and Wang, publishers), we can see the effect of Meyerhold’s staging. At first glance, the interior of the inn looks realistic. However, the more we look, the more non-realistic it becomes. The staircase is slightly disproportioned, its angle unusual. The positioning of the two actors at ground level is most disorienting. Their posture serves to skew the otherwise vertical and horizontal lines of the set. In addition, it does not look at all natural, reminding us that we are not in reality. The lighting also comes into play here. Everything is heavily shadowed; most of the back wall cannot be seen. This was important to Meyerhold’s overall nightmare theme for he wanted the action to come “forward from the gloom like the reincarnation of a long-buried past.”[52] In fact, the only time the back wall could be clearly seen was in Meyerhold’s famous “bribe scene,” when eleven bribes came through eleven doors that lined the stage. We should also note Khlestakov who is seen descending the stairs. Again, overall he looks realistic. However, his ghostly pallor, set off against his black suit, top hat, and rectangle-rim glasses, not to mention the unexplainable donut hanging from his lapel (Meyerhold never ventures to explain the donut) make him seem not at all natural, even if he is realistic.

Meyerhold did many things that likely had Gogol spinning in his grave such as his heavy departure from realism and his portraying Khlestakov as “a man who makes an art of lying.”[53] However, Meyerhold insisted he was keeping with Gogol’s vision. In the “dumb” scene, for example, all characters are to be frozen in fear for “at least two or three minutes.”[54] Meyerhold found a way to insure this would happen. The real government inspector’s arrival was announced on a large white screen, raised to cover the stage. Behind the screen, wax dummies, precisely designed to resemble each actor, were wheeled out to replace each actor (see appendix B). Hence, Gogol’s beloved “dumb” scene can now last indefinitely, even as the audience is leaving.

Reaction to Meyerhold’s presentation was, like the original, extensive and tumultuous. Meyerhold’s own assessment of his critics even resembles Gogol’s:

(My production) inspired a greater volume of critical literature than any other production in the history of the Theater. Despite the violent criticism of its alleged ‘mysticism,’ the attempts to discredit its author’s political integrity, and the hysterical protests at the liberties taken with Gogol’s hallowed text, the work was performed regularly up to the very day of (my) Theater’s liquidation in 1938. Not only did it establish once and for all the creative autonomy of the stage-director, it gave rise to numerous ‘reinterpretations’ of Gogol and other Russian classics.[55]

Once again, we see wide spread debate over the stylistic and political appropriateness of the presentation. Once again, we see that despite the debate, the presentation was at least partially effective in what it set out to accomplish:

The following was heard at the box office: ‘We are going, but we shan’t permit our children to see it.’ They realized that in our production the spectator could sense between the lines of the text – in every gesture, in every trick of staging – our hatred for the society which was overthrown by the October Revolution.>[56]

The new soviet officials disagreed with this assessment. The amorality of the “hero” Khlestakov and the non-realism of the production were seen as antithetical to the tenants of Soviet Realism and the doctrine of soviet policy, which became the official dramatic style of The Soviet Union soon after the opening of this production.[57] Before it could be banned, however, the debate sparked by the production had helped establish anti-realism as an art. It had also assured Meyerhold of the validity of his vision and the greatness of his masterpiece. He refused to make revisions, and the government liquidated his theater.

Meyerhold continued the political debate inspired by the play: “as though a Communist is incapable of writing a bad play; as though it is not possible for a Communist… to use Soviet themes as a smoke screen to hide his own mediocrity.”[58] Political reform was not to come to Russia for many years. However, the production had proven to all of Europe that realism was not necessary to stage a good production.

To conclude, we have seen that The Government Inspector occupies a unique place in theater history. In its original production, it blended vaudeville with neoclassicism and realism to change the face of Russian and world drama. In Meyerhold’s, it blended realism and anti-realism to again change the face of Russian and world drama. We can say, then, that perhaps Gogol’s drama is not best suited to one particular genre, as Gogol insisted. Rather, the simple yet powerful story, easily adapted and possessing a wide wage of possible interpretations, is best used in the experimentation of new forms. The debate over the validity of this new form is fueled by the political controversy of its striking political satire. The power of such debate has the ability to move people to topple established governments and dramatic forms. This gives true definition to Gogol’s famous quote: “What is comedy without truth and fury?”[59]

The author of this analysis, Josh Wilson holds an MA in Theater from Idaho State University. He is currently an educational consultant based in Moscow, Russia

Footnotes

[1] Milton Ehre, “Introduction” in The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), xi [2] Ehre, xxi-ii [3] Bernard Guerney, “Nikolai V. Gogol,” in Dead Souls, (New York: The Modern Library, 1997), v [4] Paul Dukes, A History of Russia c. 882-1996, 3rd ed., (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), 111 [5] Susanne Fusso and Priscella Meyer, Essays on Gogol, (Evanston, Il.: Northwestern University Press, 1992), 6-7 [6] Ehre, xvii [7] Nikolay Gogol, “The Petersburg Stage of 1835-36,” 1836, In The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 166 [8] Victor Borovsky, “Russian Theater in Russian Culture,” in A History of Russian Theater, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 6-7 [9] Ehre, xvi [10] Gogol, “Petersburg,” 167 [11] Ehre, xxiii [12] Ehre, xix [13] Ibid [14] Gogol, “Petersburg,” 166 [15] Ibid [16] Ehre, xvii [17] Ehre, xxi [18] Ehre, xxiii [19] Nikolay Gogol, “The Denouement of The Government Inspector,” 1846, in The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 188 [20] Gogol, “Denouement,” 189-90 [21] Fusso and Meyer, 5-7 [22] Ehre, xxi-ii [23] Nikolay Gogol, The Government Inspector, 1836, in The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 55 [24] Gogol, Inspector, 130 [25] Nikolay Gogol, “Letter to M. P. Pogodin,” 1836, in The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 177-8 [26] Ehre, xi [27] Guerney, vi [28] Ehre, xi [29] Gogol, “Denouement,” 189 [30] Ehre, xvii [31] Nikolay Gogol, “Fragment of a Letter to a Man of Letters,” 1836, in The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 178 [32] Ibid [33] Anatoly Altschuller, “Actors and Acting,” A History of Russian Theater, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 105 [34] Ibid [35] Altschuller, 111 [36] Altschuller, 105 [37] Gogol, “Fragment,” 179-80 [38] Nikolay Gogol, “Letter to M. S. Shchepkin,” 1836, in The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 177 [39] Ehre, xi [40] Ibid [41] Borovsky, 101 [42] Altschuller, 113 [43] Altschuller, 114 [44] Altschuller, 120 [45] Constantin Stanislavski, My Life in Art, J.J. Robins, trans., (New York: Merdian Books, 1966), 247 [46] Jean Benedetti, Stanislavski, (Bungay, Suffolk: Richard Clay Ltd, 1988), 246 [47] Ibid [48] Vsevolod Meyerhold, Meyerhold on Theater, Edward Braun, trans, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1969), 209 [49] Ibid [50] Meyerhold, 113 [51] Meyerhold, 211-3 [52] Meyerhold, 216 [53] Meyerhold, 212 [54] Gogol, “Fragment,” 180 [55] Meyerhold, 218 [56] Meyerhold, 292-293 [57] Meyerhold, 250 [58] Meyerhold, 251 [59] Nikolay Gogol, “Letter to M. P. Pogodin,” 1833, in The Theater of Nikolay Gogol, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 169