The following was originally written in Russian by amateur historian Igor Aksyuta and published on LiveJournal. It went viral on the Russian Internet for some time. It has here been translated by SRAS Home and Abroad Translation Scholar Caroline Barrow for the education and entertainment of our students and readers. Additional notes and hyperlinks have been added for English-speaking readers.

History & Myths:

Moscow State University

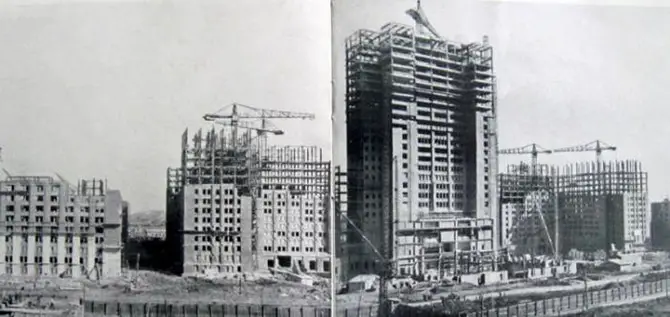

Built between 1949 and 1953, the main building of Moscow State University (MSU) on Lenin (Sparrow) Hills, was one of the largest construction projects in post- WWII Soviet Union. Before “Triumph Palace” was built, it was the tallest building in Moscow. Furthermore, until the Messertum was built in Frankfurt in 1990, it was the tallest building in all of Europe. Without the spire, the 36-story building stands at 182 meters tall, and with the spire its height is 240 meters. The picture below shows students walking in front of the building in 1951, while it was still being built.

In 1948, the Science Department of the Central Committee received an assignment from the Kremlin: to examine the issue of a new building for MSU. Collaborating with the university rector, Alexander Nesmeyanov, they prepared a memorandum which proposed constructing a “temple to Soviet science” skyscraper. Shortly after, the Moscow officials reviewed the proposal, they replied to Nasmeyanov and his team with this answer: “Your idea is unrealistic. Too many elevators are needed for skyscrapers. Therefore, the building should not be more than four stories.”

After a few days, Stalin held a special meeting about the “university issue.” There, Stalin announced his decision: a building not smaller than 20 stories would be constructed for MSU atop Lenin Hills so that it could be seen from afar.

Boris Iofan, a well-known Soviet architect famous for designing the “Palace of the Soviets,” prepared the plans for the new building. Nevertheless, a few days prior to receiving approval, his work was suspended. Then, this project was reassigned to a group of architects led by L.V. Rudnev.

The unexpected replacement left Iofan obstinate. He prepared to build the building right over one the cliffs on Lenin Hills. But, by fall of 1948, specialists were able to convince Stalin that Iofan’s proposed location was fraught with danger. They argued that the original plan was dangerous as landslides could occur, and that the new university would simply slide into the river. Stalin agreed with the need to move the new building away from the cliff. Since Iofan did not agree with this option, he was excluded from the project. Rundev moved the building eight hundred meters inland, and at Ionfan’s proposed location, he built an observation deck.

In the original drawings, the building was supposed to be crowned with massive sculpture of an abstract human. With his head to the sky and outstretched hands, the sculpture’s posture would have symbolized the desire for knowledge. Furthermore, in their presentation to Stalin, the architects hinted that this would be a tribute to him as their chief. However, Stalin ordered them to replace the sculpture with a spire, in order to make this building match the six new skyscrapers being constructed at the same time.

A solemn ceremony to lay the first stone of the new building took place on April 12, 1949 – exactly 12 years before Gargarin’s flight.

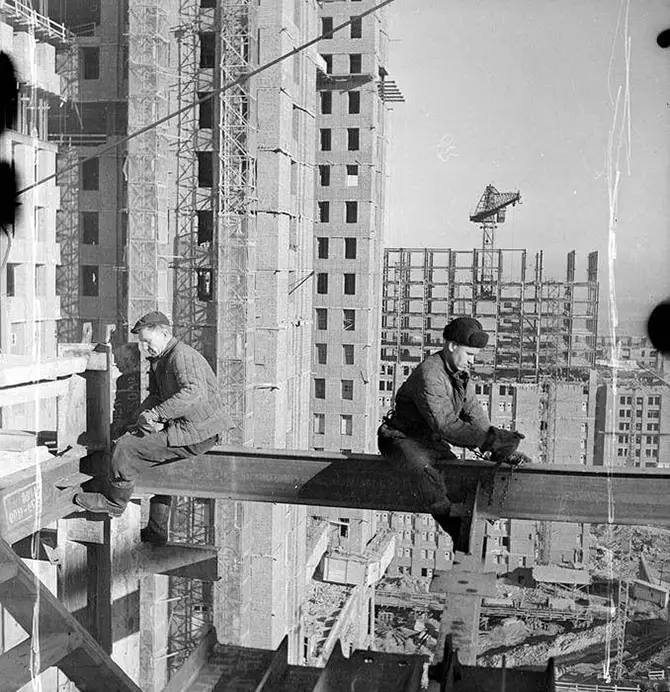

Reports from the construction say that the building used 3,000 Komsomol-Stakhonovites (who were considered ideal workers in the Soviet hierarchy). But, in reality the project used many more individuals. According to the university, at the end of 1948, the Ministry of Internal Affairs ordered the early release of several thousand Gulag prisoners who were trained construction workers. They were ordered to serve the rest of their sentence on parole in Moscow, working on this project.

In 1952, one part of the Gulag system, called “Construction 560,” was reorganized into to the “Special Region Labor Camp Administration” (known in Soviet terminology as “Stroilag”). This camp was a major part of the workforce who built MSU’s main building. General Komarovski was the camp supervisor. As many as 14,290 were held in the construction camp. Nearly all had been jailed for criminal offenses; bringing those convicted of political offences to Moscow was considered too dangerous. An area with watchtowers and barbed wire was built a few kilometers away from the “object,” which was next to Ramenky village, near the present Michurinski prospect.

When the construction of the building was nearing its end, officials decided that the prisoners should “live as close to their place of work as possible.” For this, a new camp was created on the 24th and 25th floors of the building. This solution saved money and was secure. There was no need to guard the towers nor to put up barbed wire since there was simply nowhere for the prisoners to go.

As it turned out, the guards underestimated their laborers. In the summer of 1952, a craftsman was found among the prisoners who had created a hang-glider of sorts out of plywood and wire. Various rumors tell the story differently. According to one version, he was able to fly to the other side of the Moscow river and safely escaped. According to another, guards shot him in while he was in the air. There is a yet another version with happy ending to this story in which “the flyer” allegedly made it to the ground, was caught by the KGB, but when Stalin learned of his act, he personally ordered his release based on the convict’s bravery… One version even says that the hang-glider might have carried two fugitives. At a minimum, one construction worker who was not a prisoner claimed seeing two people planning an escape from the tower using homemade wings. According to him, one of them was shot, and the second flew in the direction of Luzhniki.

This “high-altitude camp zone” has another unusual story in its history. At the time, this incident was considered an assassination attempt on Stalin. One day, while a guard was checking up on Stalin’s nearby cottage in Kunstevo, he suddenly discovered a rifle bullet on the path. Who shot? When? This disturbance was serious. Ballistic examination showed that the fatal bullet flew…from the university construction site. During further investigation, a clear picture of what happened emerged. During a change of guard, while a security guard leaving his post, pulled the trigger of riffle, which, it turns out, was loaded with live ammunition. A shot rang out. Although the shot was aimed well away from the government facility, the bullet still managed to reach Stalin’s cottage.

The new MSU building immediately broke many records. For example, the 36-story building reached 236 meters. The steel frame required 40,000 tons of steel, and almost 175 million bricks were used to build the walls and parapets. The spire has a height of around 50 meters, and the star on top weighs 12 tons. On one of the side towers is the biggest clock in Moscow. The dials are made of steel and have a diameter of 9 meters. The clock meters are also extremely magnificent. For example, the minute hand is 4.1 meters long, weighs 39 kilograms, and is twice as long as the clock on the Kremlin.

View from the building in 1952.

Residences near the construction site.

Local residents were subject to resettlement.

Stalin died a few months before the “Temple of Science” was officially opened on September 1, 1953[JW1] . Had he lived a little longer, Moscow State University would not been “named after M.V. Lomonosov” but rather “named after I.V. Stalin.” Plans to rename the university were under consideration. The name change [AB2] was supposed to coincide in time for the beginning of the new campus on Lenin hills. And in the winter of 1953, a new sign for the university was prepared, which was supposed to be installed above the eaves of the main entrance of the high-rise building. But Stalin died, and the project was never completed.

There are also many myths about this building. One story says that there are four columns of solid jade in front of the hall of the Academic Council at the rector’s office on the 9th floor. Supposedly, these came from Christ the Savior Cathedral, a famous church that was demolished in 1930 by the Soviet Regime. However, this is only a myth since there were no jade columns in Christ the Savior.

Sometimes a rumor is heard that materials from the Reichstag (German Parliament building destroyed in the Battle of Berlin in 1945), including a rare pink marble, were used in the interior of MSU. In reality, the marble in the main building is either red or white. However, it is a well-known fact that the Chemistry department is equipped with German metal filing cabinets. This indirectly proves that some of the materials used in construction were indeed from Germany.

From the outside, it seems that the spire, and also the star on top are covered with gold, but this is not the case. The spire, star, and the spikes are not covered in gold, since the wind and rain would quickly devalue the gilding. Rather, they are lined with plates of yellow glass and coated with aluminum. Currently, part of the glass is broken and cracked. If you look with binoculars, you can see gaping holes in various places.