The Leningrad Zoo was first found in August of 1865 as the private collection of Sophia and Julius Gebhardt. Although a small zoo, its history has been incredibly dramatic, surviving wars, revolutions, economic and political collapse and, perhaps most notably, the 872-day siege of Leningrad, when the whole city had to survive bombing and potential starvation. The zoo, like the city, survived only due to the willpower and ingenuity of the local population.

The Leningrad Zoo’s Early Dutch History

By Josh Wilson

Sophia Gebhardt was a charismatic immigrant from Holland who made her living selling Dutch waffles from a cart. She did it with considerable presentation, wearing a traditional Dutch costume, and she eventually found herself and her waffles very fashionable among the nobility. She soon expanded to other interests, including opening a puppet Theater, a wax museum, and even an anatomical museum in the city.

She married Julius Gebhardt, a professor of zoology and also a Dutch immigrant. Using her connections, they were able to petition the Tsar for the use of a plot of land in Alexander Park to house what was known then as the Zoological Gardens. The land was even granted rent-free.

Despite the favorable terms of the lease, the subsidy from the city the couple had hoped for was never granted and the zoo struggled financially. In 1871 the enterprise received another blow when Julius Gebhardt died of cholera.

By 1873, the zoo was nearly bankrupt. However, its fortunes reversed when Sophia Gebhardt married Ernst Rost, a German and a successful businessman who opened a Theater, a restaurant, and several carnival attractions on the grounds shared with the animal exhibits. The Theater was particularly well known for its ethnographic concerts, bringing in representatives from many world cultures to showcase their songs, dances, costumes, music, and even traditional weapons on stage.

As its fame and revenues grew, the Saint Petersburg Zoological Gardens was able to attract sponsorships as well. Ernst Rost was even able to install what were then considered luxuries for the average person in St. Petersburg: running water, sewage, and electricity (with the zoo running its own generator).

However, it also soon attracted the attention of the city authorities, who began to demand increasing amounts of rent for the land. Rost eventually found that he could no longer maintain the property. He sold it and moved back to Germany.

The zoo eventually changed hands several times, fell into disrepair, and its animals, facing neglect, were transferred to the Moscow zoo. In 1910, the park got new ownership and support from the city. By the time of the revolution, it was again known as a popular city attraction.

The Revolution Brings Education and Development

By Josh Wilson

The zoo was nationalized in 1917 as one of the first moves of the new revolutionary government. An academic committee was formed and large-scale plans were discussed to develop and reorganize the zoo. Several new buildings were constructed, excursions were held by experienced zoologists, and a youth biology program was founded (which still exists today).

Plans were drawn up to move the Zoological Garden to the more spacious Chelyuskintsev Park (now known as Udelny Park) to facilitate further expansion. However, these plans were disrupted when the Nazis invaded.

The Leningrad Zoo Under Siege

The following history has appeared in various forms around the Russian internet. It has been presented here, translated for the first time into English, by SRAS Home and Abroad Scholar Lindsey Greytak.

The Leningrad Blockade is one of the worst chapters in the city’s history. The severe winter of 1941-1942 finished what was started by the forces of a ruthless enemy. This period was difficult for everyone, many died of cold and starvation, it seemed that help was nowhere. But, even during that time there were people who did not pity themselves and tried to save the unlucky animals of the Leningrad Zoo.

How was it possible to save more than one hundred and sixty animals and birds in a city where the streets were constantly being shelled by enemy missiles, where the electricity was completely shut down, where the water mains were disconnected, where the sewage system was shut off, and where there was nothing to live off of for survival?

Of course, from the very beginning of the siege the employees of the zoo tried to save the unique animals. Eighty animals were urgently evacuated to Kazan. Among them were black panthers, tigers, polar bears, a tapir, and a massive rhinoceros. However, it was not possible to evacuate all the animals.

When the war started, about sixty zoo employees were in Belarus, having been brought to the city of Vitebsk to set up an exhibition for the local children. However, the plan was ruined by the unexpected beginning of the war. While escaping from the bombardment, the employees tried to save as many animals there as they could.Among the animals was an American crocodile. Unfortunately, they could not take the crocodile due to specific conditions needed to transport him. Someone suggested that the crocodile be released in the Zapadnaya Dvina River. This idea was supported by many, and the reptile was set free. No one has ever found out what happened to the crocodile and his fate remains unknown.

In Leningrad, during the beginning of the bombardment, the people were forced to shoot the remaining large predators. Of course, it was a shame to kill the innocent animals, however, letting them roam free to hunt, due to the destruction of the cages from the missiles, was dangerous for the inhabitants.

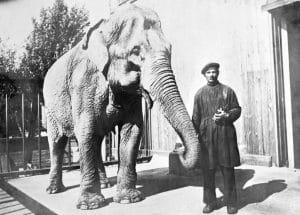

Leningrad was surrounded by the Nazis in the beginning of September 1941. At that time, bison, deer, Betty the elephant, Beauty the hippopotamus, a trained bear, foxes, a tiger, a seal, two donkeys, monkeys, ostriches, a black vulture, and many smaller animals remained at the zoo. It was not easy for them during the bombardment.

Many animals ran about their cages in horror, the bear cubs shrieked with fear, and the birds took refuge in the corner of the aviary. But the chamois (a species of goat-antelope native to Eurasia), for some reason, climbed to the top of a hill, stood there, and waited until the end of the missile strike. The elephant Betty, barely heard the sounds of the sirens in time, and hastily returned to her home. She had no other refuge to go to. Unfortunately, on September 8th one of three explosive devices dropped by German bombers exploded right next door to her, hitting a guard and fatally injuring Betty. The poor thing took fifteen minutes to finally pass away in the ruins of her elephant refuge. Betty’s funeral was held in the zoo.

The trained bear and the foxes also died that terrible night. The walls of the monkey cage were destroyed, and because of this the primates scattered throughout the district. In the morning, shaking from fear, the caretakers gathered the primates from all around the city. The bison fell into a shell crater. Nobody had the strength to pull the bison out, so they built a ramp and tried to lure the bison out with pieces of hay by spreading it from the bottom to the edge of the pit.

Another night, a goat and a couple of deer were wounded. An employee named Konovalova bandaged the animals, shared her own bread with them, and put them back on their feet. However, the poor fellow died during another shelling, which also took the lives of tigers and large buffalo.

It wasn’t easy for Beauty the hippopotamus either. She was brought to the zoo together with Betty in 1911. She was more fortunate than her friend. Beauty survived the siege and lived a long and happy life. However, if it was not for the selflessness of Yevdokia Dashina, this miracle would not have happened. The skin of a hippopotamus must constantly soak in water, otherwise it will quickly dry out and bloody cracks will cover the body. In the winter of 1942 the city’s waterpipes stopped working and the pool for Beauty stood empty.

What to do? Each day Yevdokia Ivanovna brought a 40-kilo barrel of water on a sled taken from the Neva River. She warmed the water and poured it on the poor hippopotamus. She slathered the cracks in the hippo’s skin with camphor oil – using up to a kilogram per day. Beauty’s skin was quickly healed, and she was able to live with dignity during the time of the bombardment. She lived until 1951 and died from old age. She never inherited any chronic diseases, her last veterinarians said with admiration, “Here she is! The fortitude of the blockade!”

It is to be understood that during this time the zoo was not funded, the survival of the animals was completely dependent on the employees. In the first months of the war they piled corpses of horses killed by the missiles in the field, and while risking their lives they gathered vegetables. When that opportunity was lost, people cut what was left of the grass anywhere they could while gathering mountain ash berries and acorns. By spring all the available land was turned into vegetable gardens, where they grew cabbage, potatoes, oats, and turnips.

But this can only save the vegetarian animals – so what about the rest? Although the bear unhappily ate his diet of minced vegetables and herbs, the tigers and vultures refused the meals. For them, rabbit carcasses were found and stuffed with a mixture of grass, press cake (the remains of the plant after liquid extraction), cabbage leaves, and then coated with fish oil. The employees managed not to let any of the predators die of hunger.

For the birds of prey, the employees added fish to the mixture. The vultures agreed to eat soaked salted fish. The most difficult to feed was the golden eagle, for which people had to catch rats.

It’s well known that an adult hippopotamus should consume 36 to 40 kilograms of feed per day. It should be understood, that during the blockade no such feast was possible. Beauty was given 4-6 kilograms of grass mixture, vegetables, and press cake. To this, 30 kilograms of steamed sawdust were added in order to fill her belly.

In November 1941, a hamadryas baboon named Elzi gave birth to a baby boy in the zoo. However, the mother could not produce milk, but thanks to the local maternity hospital that supplied donor milk daily, the baby hamadryas was able to live.

Surprisingly, the Leningrad Zoo closed only during the winter of 1941-1942. By spring the overworked employees cleared the paths and repaired the aviaries in order to reopen the zoo by summer. During that summer over 7,400 Leningraders came to see the over 162 animals exhibited at the zoo. This proved to be a much-needed peaceful refuge for residents during those terrible years.

Many of the employees slept at the zoo, not wanting to leave their posts for a moment. They were only few of them, about two dozen caretakers, but it was enough to save many lives. Sixteen employees were awarded the medal For the Defense of Leningrad. Later, when Leningrad changed its name to St. Petersburg after the fall of the USSR, it was later decided not to change the name of the Leningrad Zoo in order to preserve the memory of the heroism of the “staff of the Blockade.”

A big thank you to the administration of the Leningrad Zoo for the photographs.

The Leningrad Zoo Today

By Samantha Guthrie

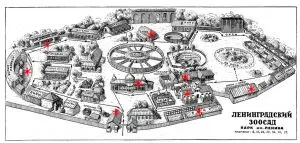

The Leningrad Zoo, located in the heart of St. Petersburg, is the oldest zoo in Russia- having just celebrated its 149th birthday on August 16, 2014. The zoo is located in Alexander Park, in the shady and quiet Gorkovskaya district in the center of the city. More than 3,000 animals from 600 species make their home here, including the favorite polar bear family! If you’re lucky, you’ll get a glimpse of the baby bear diving into the water of her habitat or playing with her mom.

Closed only briefly during the war, the zoo was refurbished in 1944, and in 1952 the name was changed from The Zoological Gardens to the present day Leningrad Zoo. You can visit the in-zoo museum “Zoo During the Siege”, where the living and working conditions of employees are recreated and fragments of bomb shells, pictures from the war years, household items of employees, and animal feed are on display. Today the zoo sees more than 600,000 visitors from all over the world each year.

When you enter the park, you initially see a petting zoo to your left and the giraffes and kangaroos straight ahead. Being a huge giraffe lover myself, I was immediately shocked and delighted by how open the giraffe’s habitat is, with low fences that make you feel as if the animals could at any moment step out and roam the park freely. The petting zoo includes goats, cows, chickens and geese. The polar bears, the symbol of the park, have their glass-enclosed habitat off to the right side. The new polar bear baby has just been named “Zabava” (fun) after a naming contest with suggestions submitted by park visitors. Other big animals include brown bears, wolves, lions, tigers, camels, and moose. There are also great collections of local and exotic birds, reptiles, and super playful monkeys! The “exoterium” is a nice break from the heat or cold, basically a miniature aquarium, this indoor space includes amphibians and sea creatures, as well as bathrooms and a cafeteria. Don’t forget to look for all the small furry animals! From foxes to nutria to lynx, around every corner is an adorable, interesting surprise.

The Leningrad Zoo also boasts several interactive exhibits. Many animal habitats have signs listing times that day when feedings or other activities will occur. The “Trail Ranger” interactive display helps you learn about the wildlife of the Leningrad region, and the “Country Life” exhibition recreates late 19th-early 20th century rural Russian life. You can even take a ride on a horse or donkey! Additionally, the zoo offers season tickets, a variety of special themed activity days and holidays, outreach and educational activities with tame animals, and more.

Although the zoo has some rough patches- it’s quite small, the climate is rather harsh for some species, bees swarm the cotton candy vendors in the summer- it is definitely worth a trip. An afternoon spent at the Leningrad Zoo will be both fun, educational, and full of great photo ops! It’s also an excellent way to learn and practice animal names in Russian!