As a historian of World War II with a focus on Holocaust studies, visiting Poland was a must since the atrocities of Hitler’s Final Solution predominately occurred in Poland. Today, there are countless commemorations to the Holocaust on almost every street in Poland, it seems. Museums tell the stories, plaques mark the walls of buildings, monuments, statues, and memorials are erected in the historical places where the events once happened.

But to have a deeper sense of trying to understand what took place from 1939 to 1945, a tour of Auschwitz-Birkenau is essential. From Warsaw, it is an easy, two-or-three hour train ride to the camp. However, actually being there will not be easy.

After leaving Auschwitz-Birkenau, I was left with a sense of unsettlement that I was not able to shake for several days. My feelings of the experience had at Auschwitz can be quite controversial, but it is worth mentioning in hopes of changing the way American tourists visit this horrific place of history as well as hoping to encourage Americans to remember the Holocaust.

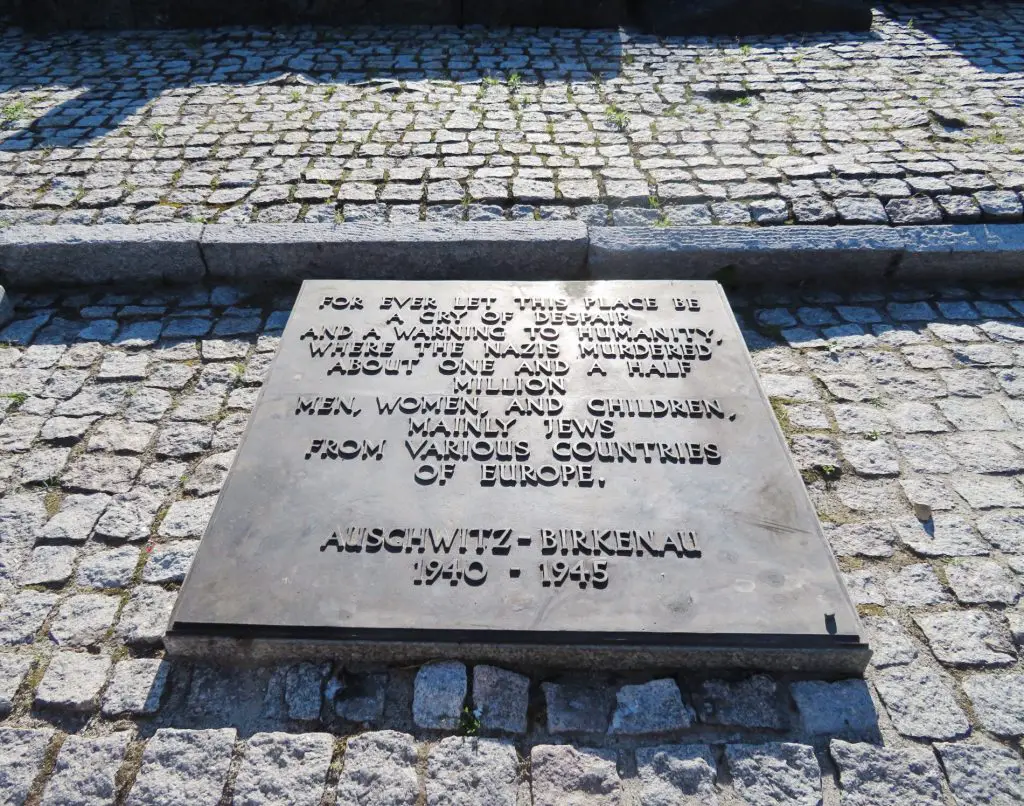

The symbol of the Holocaust is Auschwitz-Birkenau, the former German Nazi concentration and extermination camp. It is the symbol of genocide; it is the symbol of true terror.

Auschwitz-Birkenau was originally opened in 1940 as a camp for Polish prisoners. The local prisons were too small for mass arrests made by the Nazis, so during the summer of 1940, the first transport of Polish prisoners arrived at Auschwitz. The number of prisoners in Auschwitz at any one time, with fluctuation, was usually between 15,000 to 20,000. Auschwitz, also referred to as the “main” camp or Auschwitz I, was a concentration camp, and it was a place of slow killing. Many prisoners died of physical and mental abuse, inhumane conditions, and especially starvation.

But as the war went on and Hitler’s plan for the outcome of the Jewish people changed from ghetto relocation to the Final Solution extermination plan, the Nazis built a second camp, Birkenau, also known as Auschwitz II. It was located about three kilometers from the main camp, and was larger. It was established as an extermination camp for the transport of Jews coming from German-occupied Europe, and it was a place of mass murder by using Zyklon B gas, but also death by individual executions, forced labor, physical beatings, starvation, illness and disease, and medical experiments.

The majority, about 90%, of those who perished at Auschwitz-Birkenau, died in Birkenau. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, an estimated 1.3 million people were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau; out of the 1.3 million, 1.1 million died at the camp. Nine out of ten deaths were Jews; one of six Jewish deaths during the ruling of the Third Reich happened at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Those numbers are so astronomical, that it is almost impossible to even wrap your mind around the sheer horror of what happened to so many hundreds of thousands of innocent people. Yet, it happened.

Today, Auschwitz is listed on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site, about two-million people visit the camp per year, and the Daily Mail once wrote an article calling Auschwitz the “world’s most unlikely tourist hot spot”.

But despite reading about the Holocaust all of my life, and in the most recent years having done scholarly research on the subject, there was nothing that could prepare me for what I was going to see at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The tour began at the main camp. My tour guide was Polish and a local of the area, and both of her parents were held as political prisoners for a short time during its operation. I was led through a security check, handed my audio guide, and began the walk to the entrance of the prison.

Written on the gate into the concentration camp is “Arbeit macht frei,” the German phrase meaning “work sets you free.” That phrase alone, knowing now what happened in Auschwitz, had my heart beating uncomfortably fast.

I was taken through several of the twenty-eight barracks of Auschwitz I. One barrack showed the living and sleeping arrangements. Another barrack showed where the suffocation room and the starvation cell were located. Other barracks are now used as a museum to display artifacts from those brought into the camp: forty-thousand pairs of shoes, an unbelievable amount of shaved hair from the prisoners, mangled bifocals and glasses, cans of the Zyklon B pellets of hydrogen cyanide.

I was taken through the bathroom where prisoners were told to strip and relieve themselves before being taken to the “Black Wall.” the execution alley located between the medical-experiments block and prison Block 11. Thousands of prisoners were executed here by firing squad.

I saw the walls covered by the hundreds of photos of inmates, both men and women, with shaved heads, wearing the striped uniform, and only identified by the number assigned and tattooed on each prisoners’ forearm.

I walked through the remaining gas chambers and crematory, and from there, I was led back to the entrance where I then took a bus to Auschwitz II.

Once entering the main entrance, everywhere you turn, looks upon the camp. You look out on this long dirt path, and squinting into the sun, you see nothing but barracks, watchtowers, barbed wire fences, and a railroad track. And you are greeted with a sense of dread. You have entered the “death gate.”

On that particular day, it was uncomfortably hot. The sun was so bright, and the sky was clear. And anywhere else but then, I would have welcomed the sunshine. But as I followed my guide who had an umbrella to shade her face, I remember thinking how it was too hot to walk the almost mile to the other end.

We stopped halfway at the only remaining cattle car. These cattle cars were filled with usually one hundred, give or take, Jews that were being brought into the camps, and without these trains, the extreme number of deaths would have never been possible. The trains were loaded at various ghettos and then traveled for hours, sometimes up to two days, to the destination, and many didn’t survive the trip. The Jews had been told that they were being resettled to the east, most likely to a labor camp in Ukraine. This “resettlement plan” was to keep from mass hysteria, but the reality is that these trains were heading towards a destination intended for mass murder.

Once unloaded, the men, women and children were separated. The very sick, the very old were often immediately shot. The very healthy men and women that could work, were immediately assigned hard labor. The rest were sent to the gas chambers; they walked a long path after a long journey, only to be told to strip for a “shower.”

During the height of its operation, up to 6,000 Jews were gassed per day at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

From the selection process area, we continued the long walk to what remains of the underground gas chambers and the crematories. Here, our guide had us stop for a moment to look at the rubble. From the far right, there was an entrance where the Jews were forced to strip, becoming completely naked. From there, they entered a room that was built to model a shower. But instead of water pouring from the ceiling, poisonous gas entered the room, killing every person. There was no escaping; they had been locked into the chambers. After the last death, the bodies were then moved into the crematories where they were burned into nothing but ash. These ashes were then dumped behind the gas chamber and crematory into a field with an “ash pond”.

From the gas chambers, our tour guide walked us to the last stop of the tour: the women’s sleeping barracks. Some of these barracks had no windows for ventilation; others had only one chimney to warm the entire building during the brutally cold winter months. Diseases were so easily spread in this cramped living spaces. Diseases like typhoid took the lives of so many. Lice was a serious problem in many of the concentration camps. As many as eight women would be forced to sleep on a bunk; the worst place to be was at the bottom level. Here, you were at risk of having someone too tired or too sick to walk to the toilets, relieve themselves on you. It was freezing in winter months; it was sweltering hot in the warmer months.

Truthfully, I did not know what to expect when visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau. This was a place that I have spent countless hours reading about, desperately trying to make sense of the horrors that occurred on the camp grounds. I have met multiple Holocaust survivors, most of them survivors of Auschwitz, and within the last two years, I have developed a personal relationship with a survivor who now resides in Beverly Hills, California. I have sat across from her, interviewing her about her time in the camp, pressing about the sights, the smells, the memories – and nothing can prepare your heart or mind to handle the tears that come into the survivor’s eyes.

So when I entered Auschwitz-Birkenau, I entered with the image of Hana in my mind. But what I did not expect, was to leave not immediately thinking about Hana, but instead, the lack of total disrespect and disregard that I had witnessed throughout my entire day at Auschwitz.

One of the first things I noticed when arriving outside of the main camp was how loud it was. There were hundreds of people, everyone running around and meeting up with their groups. So much laughter and giggling; loud conversations in various languages. Girls and women were wearing sleeveless, strapless tops with shorts or skirts that showed their entire legs. I saw so many men in cut-off shirts and shorts. Bright colors and big patterns flashed all around. People were sipping on their Cokes or coffees, snacking on food items purchased from the café, snack bars, or vending machines.

My initial thought was that I had entered some sort of amusement park, not a former German Nazi concentration and extermination camp. But I hoped that once I entered the camp and began my tour of the buildings, barracks, and museum, the visitors surrounding me would observe the rules in regards of showing solemnity and respect.

But I was greatly mistaken.

As I went through barrack after barrack, I was shuffled along in lines, pushed from the back, slamming into the person in front of me. I wasn’t given the true opportunity to stop and observe what I was seeing. People were abrasive and loud, often yelling to a friend that was across the hall. I was severely distracted by the amount of selfie sticks that were blocking views. I saw phones out with the Snapchat app open. Young teenagers and adults were taking group photos on the grounds, and to my utter disgust, I saw a middle-aged couple taking a smiling selfie with their iPad in front of the barbed wire fence – the same barbed wire fence that once kept prisoners from escaping into freedom.

As I walked towards the exit, I passed a woman who was strolling the grounds, munching on chips from a bright blue bag. That woman with her bag of chips, is an image that my mind cannot erase.

At Auschwitz II, I was saddened to see that even there on the grounds where the majority of the deaths occurred, people still showed such a lack of respect. On the walk towards the remains of the gas chambers, I saw a group of teenagers, ages thirteen to fifteen, and they were joking and playing with one another, kicking dirt clots at each other’s feet. At the gas chambers and crematories, so many people had their phones out texting or browsing social media, completely ignoring their guide. And once I entered the women’s sleeping barrack, I was taken back by people casually sitting in the wooden bunks taking pictures; I was also shocked to see the amount of graffiti written all over the walls and beds.

I ended my tour of Birkenau by going to the main tower that overlooked the entire camp. In the watchtower there was a family, husband and wife and three grown children, and they were all laughing and high-fiving one another. The husband and wife were hugging and kissing. Why? How? I was appalled.

I do believe that the employees and board members of Auchwitz-Birkenau could make possible changes to enforce more strict rules and respectful behavior by doing things such as enforcing a dress code, not allowing cell phones, selfie sticks, or Go-Pros, and possibly even having requirements in regards to the age you must be to enter the camp. Although it is imperative that as many eyes see Auschwitz-Birkenau as possible, maybe there should be a restriction on how many visitors are allowed in per hour or even per day.

But the problem isn’t with the way that the Museum is presented or even run. The problem is with the visitors and the overall lack of solemn respect given to those who once occupied those camps as prisoners.

The New York Times did an article back in the early 1990’s on a study done by a sociologist on local Holocaust survivors and the post-traumatic disorders they have had to deal with following liberation. The most common sign of post-traumatic stress among the survivors was frequent nightmares; some studies found that the rate of having nightmares about one’s experience was as high as 80%. One survivor told the dr., “If you have been through Auschwitz and you don’t have nightmares, then you’re not normal.”

One of the things I stress in my writings regarding my research and studies, is to remind people today, especially the generations so far removed from WWII and the Holocaust, is that it is so easy for us to walk away from the horrors of Auschwitz-Birkenau. We did not experience it; we did not live it. We can go see the recent Hollywood blockbuster hits or read the latest best-seller on the Holocaust, and then forget it all. We can visit the memorials and museums and tour Auschwitz-Birkenau and leave without the fear of having repeated nightmares.

But that isn’t the case for the survivors. They cannot walk away from the memory of the Holocaust. They cannot forget the horrors they experienced.

So when you visit Auschwitz-Birkenau, remember those who were liberated but lived with the pain and guilt of surviving. Remember those innocent men, women, and children that suffered at the hands of mankind, perishing and becoming nothing but ash. Look at the photos of the prisoners, and see them not as a statistic or a number but as a human being. Try to count the number of shoes. Stand in front of the suffocation room or the starvation cell and try to grasp what hell those men and women endured.

To my fellow American tourists, when visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau, put away your social media check-ins and selfie sticks. Dress modestly and appropriately. Speak in hushed tones, and truly take in what it is you’re seeing. Stop and reflect on what you experienced.

Auschwitz-Birkenau is not a place of entertainment. It isn’t a place to visit just for the sake of saying you’ve been there. It isn’t a bucket list destination.

We owe more to the those who suffered at the hands of Hitler and his Nazi regime to just walk away, forgetting.

Do not forget those who perished. Do not forget those who survived. Remember the names, not just the numbers. Learn the individual stories of those who entered the camps. And when you leave after touring Auschwitz-Birkenau, I hope that you leave with the sense of responsibility that you will never forget what you witnessed during your day at Auschwitz-Birkenau.