Before the invention of laser eye surgery to correct vision impairments, Tatyana Tolstaya was faced with a tough decision: suffer through poor vision, or undergo a long surgery involving medical razors. She chose the latter. Through a long convalescence, her eyes covered and unseeing as they healed, she was surprised to discover an “aetherial world through a looking glass” in her imagination. She began to put to words the fictional stories she imagined and eventually carved a place for herself as one of the leading writers in contemporary Russia.

The Early Life of Tatyana Tolstaya

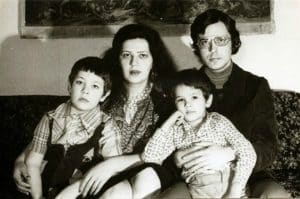

Tatyana Tolstaya was born in Leningrad on the 3 of May, 1951. Her father, Nikita Tolstoy, was a professor of physics and her mother, Natalya Lozinskaya, was a stay at home parent that tended to the family. Tolstaya grew up along the Karpovka River Embankment, centrally located in what is now St. Petersburg. Her upbringing revolved around her large family which consisted of six brothers and sisters.

Writing runs deep in Tolstaya’s blood, as both sides of her immediate family also contributed greatly to the Russian literary tradition. Distantly, she is related to both Leo Tolstoy and Ivan Turgenev. Natalya Krandievskaya, a poet and memoirist, was Tolstaya’s grandmother while her grandfather was Aleksey Tolstoy, author of the beloved 1936 children’s book The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Buratino.

Following the lead of her artistically minded family, Tolstaya attended Leningrad University where she studied classic literature, Latin, and Greek. She graduated with a degree in Classical Philology in 1974. That same year, she married Andrei Lebedev, also a philologist and classicist.

The pair moved to Moscow, where Tolstaya proofread for the Oriental Literature department of Nauka Publishing House, then the USSR’s largest publishing company for academic books and magazines. In 1983 she left that job and began to write her own works as a literary critic, the first of which came out in the magazine Questions of Literature.

Later in 1983, Tatyana Tolstaya underwent her eye correction surgery. Tolstaya says that afterwards, “I had to lie with the bandage for a month. And since it was impossible to read, [my] first stories began to appear in my head.” Up until this point, Tolstaya never considered a career in literature despite her family’s success in creative endeavors. Although she admitted she “happily swam in [the] imaginary expanses” of her daydreams, she “had no words to describe them.” Once the bandage was removed, however, she said that her “visual experiences now came with a narrative.”

The Professional Life of Tatyana Tolstaya

Soon after, Tolstaya wrote a short story for Aurora magazine entitled “On the Golden Porch.” In this story, she explores the reoccurring motif of outwardly normal individuals with vibrant imaginary lives. The plot of “On the Golden Porch” centers on the childhood memories of a lively uncle and the “magic lantern” of his youth. The story was received positively by both readers and critics, as Tolstaya’s writing invoked in readers a wide array of emotions through relatable childhood memories. This topic is deeply personal for Tolstaya, who claims to have lived “in darkness” before her vision was medically corrected.

“On the Golden Porch” was translated to English in 1987, and reviewed by Kirkus Reviews, an American magazine. The company deemed her writing “richly textured” and further noted that what is “impressive here is Tolstaya’s idiosyncratic use of language and metaphor.” After the positive reception of her first short story, Tolstaya published more stories in The New World magazine, Russia’s oldest monthly literary and art magazine.

In 1987, during Perestroika, Tolstaya published her first collection of short stories entitled On the Golden Porch. The stories are principally set in Moscow and Leningrad. The protagonists are not archetypal heroes – they are idealists, children, fools, and underdogs going through everyday domestic issues, each with their own imaginary worlds filled with dreams and fears. In the West, On the Golden Porch was well received by reviewers. For example, Richard Lourie wrote in The Washington Post, that Tolstaya has “piercing insight” into the ordinary lives of people and has complete “control of her craft.” She was further praised by Lourie for featuring everyday characters rather than knights and princesses, as it made it clear that “her theme is life and her heroes [are] everyone.” He compared her writing to famous Russian writers, saying her “tone is muted with Chekhovian sadness, sometimes it is jagged and grotesque like Gogol.”

In the Soviet Union, readers also responded positively. To date, she has sold over 85,000 copies of On the Golden Porch. Moreover, after the release of the collection she was admitted as a member of the Writers’ Union of the USSR. Despite this, not all Soviet critics responded warmly. Tolstaya was criticized by Andrei Nemzer, a Soviet era literary critic for Ogoniok magazine, for the “density” of her writing and because “you could not read a lot in one sitting,” due to a heavy-handed use of symbolism and metaphor. He further stated Tolstaya’s “aestheticism was more important than her moralism.” On the other hand, Tolstaya was also credited for being an original and independent writer.

The short stories of Tatyana Tolstaya are deeply rooted in the Russian literary tradition, with influence drawn on both Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol. The pair were known for stories that delve into the fantastical, where dream blends with reality. An example of this can be seen in Gogol’s Nevsky Prospect where the main character’s romantic ideals make him unable to distinguish between dream and reality.

Furthermore, Pushkin and Gogol often center their stories on “the little man.” In the Russian literary tradition, this refers to an ordinary character beaten down by society. Similarly, Tolstaya’s stories chronicle the lives of social underdogs with such lively imaginations that sometimes the reader cannot tell whether what is happening is true. In the story “Peters” in On the Golden Porch, for example, a chubby librarian dreams of all the attractive women he will date once he learns the German language. The reader is led to believe the librarian may have a chance with a fantastic, and attractive, lady until she is heard calling him a “wimp.” Like the stories of Pushkin and Gogol, Tolstaya’s tone has hints of darkness, but is overall lighthearted.

Emigration to the US

Tatyana Tolstaya left for the United States in 1990, as the Soviet Union began to collapse. She then taught Russian literature at Skidmore College. Throughout the 1990s Tolstaya lectured at multiple universities as well as wrote for the New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, and The Times Literary Supplement. She also kept writing for Russia-based publications as well. In 1991, she wrote her own column in the weekly newspaper The Moscow News, an English publication created for foreigners in the USSR, and wrote essays and articles for Russian Telegraph. She also wrote for Capital, of which she was a member of the magazine’s editorial board.

As her reputation as an intellectual grew, she also co-wrote a new collection of stories with her sister Natalya. Published in 1998, it was entitled Sisters. This book shows a stylistic connection between the two sisters with a similar world view. In the collection, the sisters write in different genres: Tolstaya acted as a journalist, telling stories through facts and essays, whereas Natalya filled the collection with rich short stories exploring ordinary Russian lives. The collection was translated into English, German, French, English, and Swedish. Sisters sold over 20,000 copies in Russia alone. Critically, reviewers were disappointed that Tolstaya did not write any fictional stories but warmly received Natalya’s writing.

In her time in the United States, Tolstaya was disappointed to see how Russian immigrants made changes to their native language because of the influence of English. She wrote a short essay on the subject entitled “Hope and Support” that details how words in Russian and English get tossed together to make an entirely new language that was incomprehensible to her. After only four months in America, she notes, her “brain turns into minced meat or salad, where languages are mixed and there are some undisclosed words that are missing both in English and Russian.”

Return to Russia

In 1999, after nearly a decade abroad, Tatyana Tolstaya returned to Russia, where she apparently still found dissonance in everyday life. In 2000, Tolstaya released The Slynx, a story of post-apocalyptic Russia after a nuclear war. In the novel the Slynx, a dreadful creature, haunts the main character, Benedict but is never seen and is more likely a symbol of the characters’ fear of the unknown rather than something tangible. The Slynx has sold over 60,000 copies in Russia. Critics praised Tolstaya for her subtle use of humor in a relatively serious novel. For The Slynx she was awarded both the Triumph Prize in 2001, a Russian award for the highest achievements in literature and art, and the XIV Moscow International Book Fair Prize for Prose.

In 2002, Tolstaya’s rising profile led to an invitation to co-host School for Scandal, a TV talk show, with Avdotya Smirnova. The two interviewed politicians, actors, and television personalities. After the guests vacated the stage the co-hosts began to “psychoanalyze” them. The goal was to reveal hidden qualities of the guest, not known by the public and sometimes not even known by the guest. In 2003, Tolstaya and Smirnova received the Russian National Television Award for Best Talk Show.

Avdotya Smirnova and Tatyana Tolstaya interview the director of Snob magazine, a popular intellectual publication, on School for Scandal (in Russian, no subtitles).

In 2010, Tolstaya co-authored a collection of poems for children called The Same ABC of Buratino. The book had one entry for each letter of the Russian alphabet and each interconnected with The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Buratino, Tolstaya’s grandfather’s famous book. In an interview with Natalia Vertlib for Mama magazine, Tolstaya said she had been planning this book since her childhood, but as years passed she “switched to stories” and, after her children grew up, she finally had time to return to Buratino, and this “half-forgotten project was picked up” by her niece. Since its release, the book has sold close to 50,000 copies. During the XXIII Moscow International Book Fair, the book was awarded second place in the Children’s Literature category.

Return to Fiction for Tatyana Tolstaya

Recently, Tolstaya returned to writing fiction with the release of Aetherial Worlds in 2018. The book is a compilation of short stories that depict the lives of everyday characters with dreams that enable the characters to transcend this world into the next. The collection was praised by reviewers. Sam Sacks for The Wall Street Journal deemed it “playful and poetic” and Lev Grossman for The New York Times called it “marvellously vivid, [and] perfectly tuned.” Since its release in March 2018, Aetherial Worlds has already sold 10,000 copies.

One story in Aetherial Worlds shows Vladimir Nabokov’s influence over Tolstaya’s writing. Nabokov is a Russian author known for his manipulation of time. “The Return of Chorb,” for instance, follows a non-linear narrative tale of a man trying to re-create the past after his wife’s death. Tolstaya explores time similarly in “The Invisible Man.” The story begins in the main character’s family dacha in the implied present, but then moves to encompass the character’s entire life – past, present, and future. Similar to Nabokov’s character searching for pieces of his wife by reliving the past, Tolstaya explores the intricacy of time to show how things transform in unexpected ways.

Today, the literature created by Tatyana Tolstaya is canonical. She is an influential intellectual as well a household name in Russia. She has published over twenty books, three of which have been translated from Russian into English and released in the West to much critical acclaim. Her work in fiction enabled her to experiment with television, children’s literature, and non-fiction. To this day she continues to write articles for multiple magazines including The New Yorker. Furthermore in 2011, in the culmination of her literary career, Tolstaya was awarded the Russian equivalent of the Booker Prize, the Student Booker of the Decade award, for which she was nominated on a short-list compiled by student representatives from various Russian universities.

Since her eye surgery in 1983 opened her eyes and mind to fiction, Tatyana Tolstaya has left a lasting impact on modern Russian literature. Her stories serve as motivation to everyday people and underdogs who dare to dream, as, according to Tolstaya, eventually “the doors [to your imagination] will open, and you won’t know what you will come across until you enter.”

Tatyana Tolstaya in a talk with Maya Vinokour, at the New York University Jordan Center to discuss her short story collection Aetherial Worlds, the process of translation, and authors that inspire her.