Futurism, an artistic movement started in Italy, quickly found fertile ground in Russia starting in 1909. Futurism thus emerged in Russia in the period between the 1905 and 1917 revolutions when artistic, social, and political thought were in foment. Russia’s unique brand of Futurism helped form the basis of the Russian avant-garde, conveying its social and political ideals and rejecting traditional conventions in the pursuit of technology-based progress.

Eventually, a wide variety of artists would come to apply its tenets of subjectivity and ultra-modern design to a wide swath of mediums, including literature, painting, music, sculpture, and architecture.

Defining Russian Futurism: Hylaea and Poetry

The Russian Futurist tone was set by the group Hylaea. Formed in 1910 by poet and artist David Burliuk and his brothers, they gathered some of the era’s most revolutionary talents.

In a move of purposeful irony, their name is rooted in the ancient past. Hylaea refers a forest grove near the mouth of the Dnieper River, which the Scythians considered to be the mythical birthplace of their people. The name was fitting, however, as the Futurists sought a rebirth, one that would cleanse and prepare humanity for a new era. The Futurists knew that this would not come without a fight, however, and thus chose to be associated with a people known as fierce warriors.

Their 1912 manifesto, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, written primarily by poet and playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky, is considered one of the most memorable in an era saturated with artistic manifestos. Remarkably short, it calls out a whole list of revered past writers as outdated and demands that current artists be allowed to reinvent language and be separated from any need for public approval.

Hylaea advocated their art through intentionally provocative publications, lectures, and performance art, all of which melded their aesthetic with a forward-looking political consciousness.

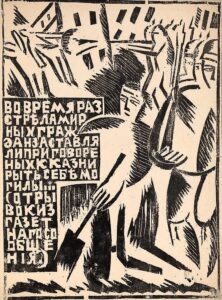

Many of Russia’s earliest Futurists were writers. They sought a rebirth of language, one that would make it both free and highly concise and efficient. This was expressed in styles like Mayakovsky’s terse and often violent verse, which borrowed themes from both religious and romantic poetic traditions, but encapsulated it in an anti-war, anti-bourgeois, and linguistically blunt and visceral frame. Mayakovsky also participated in creating silent films and posters that adopted a similar style.

In the late 1920s, Mayakovsky integrated more satirical criticism of Soviet bureaucracy into his plays, which eventually cost him his ability to produce them as that bureaucracy gained more power over artistic production.

Aleksei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov developed a literary style using invented language. They called it “zaum,” which translates loosely from the Russian as “beyond understanding.” The new style sought to convey meaning and emotion through carefully arranged sounds, detaching language from convention to explore how words could revolutionize meaning.

While Khlebnikov primarily kept his experimental prose within his poetry and plays to explore its linguistic power, Kruchenykh frequently lent it to multi-media and often collaborative work, searching for ways to stretch language into image and sound.

Kruchenykh authored books illustrated by Olga Rozanova’s Futurist watercolors. He also collaborated with composer Mikhail Matiushin on a 1913 opera, Victory Over the Sun. The opera combined rapid, discordant music with terse dialog, vocalized sounds, and lots of moving, linear, geometric shapes using the set, costumes, and props designed by Futurist painter Kazimir Malevich.

Likewise, Vasily Kamensky was a Futurist poet known for integrating his Futurist poetry with not only illustrations, the most well-known being from David and Vladimir Burliuk, but also using the layout of his own text to create meaning and convey emotion from its visual form.

Above: Watch Victory Over the Sun in full, for free, on YouTube. This is a 2015 production, based on the original, created Stas Namin Theater in Moscow in cooperation with the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. It was performed at the Theater Basel in Switzerland.

Russian Futurism in Painting, Architecture, and Sculpture

Given the amount of collaboration the Futurists sought in their search for meaning and expression, it is not surprising that their ideas rapidly seeped into other art forms.

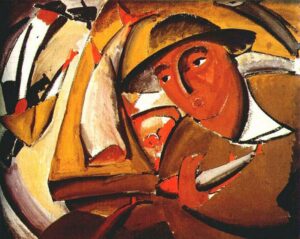

Natalia Goncharova, another early member of Hylaea, perhaps best set the tone for what became the recognizable elements of Russian Futurism in painting. Called Cubo-Futurism early on, her style mixed Futurist philosophy and subjects with the Cubist focus on geometric and three dimensional shapes. From around 1910, her oil paintings contrasted dull and vibrant colors while using defined and angular lines with thick brush strokes to mix shaded, repeating geometric shapes with words, numbers, and other symbols to achieve dynamic portrayals of working class Russian life. Goncharova is also known for her writing and design.

Fellow painter and Mikhail Larionov worked in collaboration with Goncharova, using similar geometric Futurist depictions of technological and urban themes as well as folk life.

Vladimir Tatlin was a painter, sculptor, architect, and designer who incorporated a geometric portrayal of technology into his work. His oil paintings from the second decade of the twentieth century utilized sculptural elements and dynamic shapes, which through their bright colors, shading, textured brush strokes, and heavy lines came together to portray everyday subjects in bold and simplistic style.

Other examples of Tatlin’s work use similar shading and textural techniques to paint structural clusters of shapes, with their word labels as an integrated part of the painting.

He also worked to transfer Futurist philosophy and aesthetic to Constructivist utilitarian object design via sculpture and architecture in the 1920s and 30s, using soaring lines and basic materials such as wood and steel to invoke curving technological constructions of the future. This type of geometry also dominated in Tatlin’s stage and object design, combining three-dimensional, angular landscapes and linear objects ranging from chairs to dresses.

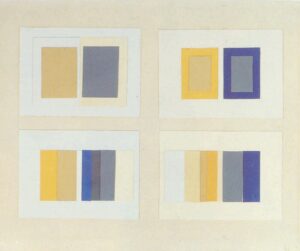

Mikhail Matiushin, the composer of Victory Over the Sun, was also an oil painter who used simple and colorful brushwork. In all his work, he strove to explore the extent of human perception. He and poet and writer Elena Guro were two of the first Russian artists to examine how perception is altered in an urban environment.

Russian Futurism’s Legacy

Russian Futurism was the progenitor of many other avant-garde movements in Russia, including Suprematism, Rayonism, and Constructivism. However, beginning in the 1920s a surge of Soviet censorship escalated, with the Soviet government officially declaring Socialist Realism its only sanctioned art form in 1934. Russian Futurism was not compatible with Socialist Realism’s romanticized image of the proletariat.

Khlebnikov, Rozanova, and Guro all died of illness before 1925 while Mayakovsky committed suicide in 1930. Surviving Futurist artists either found their work no longer commissionable or were forced to adapt it, such as in state-approved posters or, via Constructivism, to everyday objects, where certain elements of the style were still acceptable.

And yet, Futurist influences permeated Soviet life and philosophy long after it and its proponents were left behind. Russian Futurist emphasis on technology, geometry, dynamism, and the application of art to urban and rural proletariat subjects alike was employed in Russia throughout the twentieth century primarily through the work of the Constructivists. Thier work on considering page layout and illustration to be holistic art would eventually enter mainstream publishing, especially with children’s books.

The legacy of Russian Futurism was also universal, forming a key buttress for Modernist art in the mid and late twentieth century and beyond. However, Russian Futurist art further represents a clear ideological assertion which has been considered in every subsequent era: namely, a unique, technological affirmation of the dynamism which is imbued into life.