Natalia Goncharova, along with her colleague and companion Mikhail Larionov, led the charge in Russian Futurist painting, or Cubo-Futurism, in the early twentieth century. While her early work was heavily influenced by the French Post-Impressionists, she went on to help develop Primitivism, Rayonnism (specifically the brain-child of Larionov) and various Futurist theatrical experiments. When the pair went to Paris with Sergei Diaghilev in 1914 to work exclusively on stage design, they left behind a Russian art scene forever changed by their creative new forms, rattling public performances and artistic manifestos.

Natalia Goncharova was born in 1881 to a Russian family of noble lineage. Her father’s mother’s line connected directly to Aleksandr Pushkin. Her father’s father’s line ran back to an architect of Peter the Great. Natalia’s mother, meanwhile, came from the Belyaev family, which had been extremely musically influential in the nineteenth century.

She was born in a small village south-east of Moscow in the Tula province and actually grew up in the country, albeit in a large estate. When she moved to Moscow at the age of seventeen to begin her studies at the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, she completely retained her attachment to country life. These origins set her apart from her fellow Cubo-Futurists in two ways. For one, she came from a family with money and nobility, while most Cubo-Futurists came from peasants or tradesmen. Secondly, she was staunchly anti-urban, a trait which united her more with the Italian Futurists than the Russian. This tendency shows most in her later work, from 1912-14.

At Moscow College, Natalia took lessons in sculpture from Pavel Trubetskoi, an artist of the World of Art. She later switched to painting and met perhaps the most influential man in her life, Mikhail Larionov. The two became inseparable, both in their professional and personal lives.

In 1906 Goncharova and Larionov exhibited their works at a World of Art exhibition put on by Diaghilev, and he subsequently invited the pair to exhibit in Paris at the 1906 Salon d’Automne. Goncharova’s professional relationship with Diaghilev didn’t end there, and in 1914, after having spent eight years developing and perfecting her artistic techniques in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, she returned to Paris to work again with Diaghilev on stage designs for his Ballets Russes.

The years 1906 through 1914, however, witnessed in Russia an extraordinarily rapid series of artistic shifts and turns. Diaghilev joked during this time that twenty schools sprung up a month, and Goncharova was at the forefront of many of the major ideas and innovations. She participated in both the 1909 Golden Fleece and 1912 Jack of Diamonds exhibitions. The Post-Impressionists had an enormous influence on the Cubo-Futurists, and in particular during the Golden Fleece period one can feel the exaggeration and high drama of Toulouse-Lautrec in Goncharova’s work. Always paying more attention to decorative elements than Larionov, Goncharova used the bold lines and the thick, undiluted colors of the Fauvists to capture raw energy with seemingly sparse and simple elements.

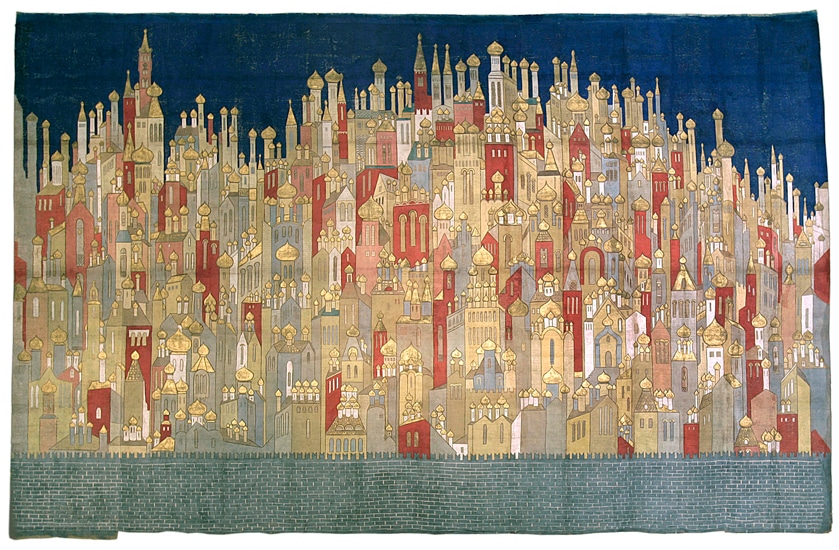

By the time of the last Golden Fleece exhibit at the end of 1909, Goncharova had turned her love of peasant culture and country life into her own brand of Primitivism. This movement drew inspiration from Russian icons and folk art. Of particular influence were the Russian luboks. These were a kind of political/religious morality book, produced and disseminated to the peasantry in the seventeenth century. In the early twentieth century, their simplified style of presentation was taken up eagerly by artists in both Germany and Russia who were interested in primative forms of style and narrative. Goncharova was personally able to expand the breadth and depth of the Russian Primitivist movement by introducing many Cubo-Futurists to the influence of ancient, restored icons, then housed only in private collections.

From there, Goncharova put her own mark on Primitivism, enlivening it with her own brand of design and ornamentation. She masterfully melded the French Fauves’ bold use of color with the simplicity and emphatic energy of icons, luboks and peasant wood blocks. The resultant paintings serve on the surface a simple, illustrative function, but they’re also brimming with emotional potency. Goncharova was attracted to the straightforward and the bold, but she could find subtleties in this boldness, and even her thickest expanses of paint vibrated with complexity.

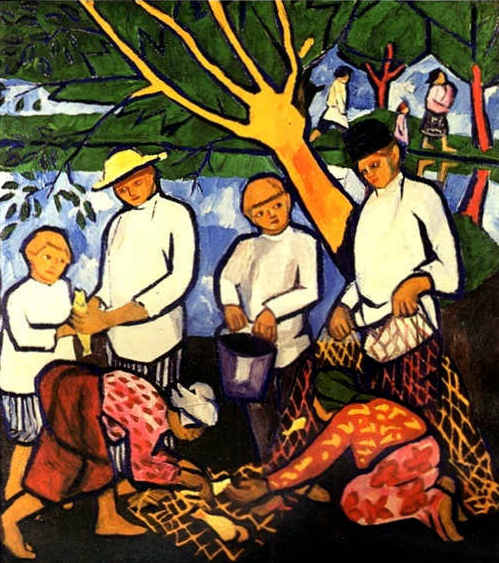

Goncharova continued to exhibit her Primitivist pieces, such as the 1910 work Fishing, at the Jack of Diamonds shows in 1912. These brought Goncharova and Larionov briefly together with Wassily Kandinsky and the Burliuk brothers, David and Vladimir, Russian members of the Munich school. They also introduced the pair to Kasimir Malevich, who would emulate Goncharova for much of his career and take over the Cubo-Futurist movement once the pair left Russia. However, these brief experiences at the Jack of Diamonds exhibitions seem to have convinced Larionov and Goncharova to turn away from the influence of foreign artistic movements and to develop their own purely-Russian style. During this time, it is said that they were “so extreme in their nationalist ideas that they had shaken off ‘Munich decadence’ and the ‘cheap Orientalism of the Paris School’” (Gray 122).

Larionov held two major exhibitions in the wake of this rift, and of course Goncharova exhibited at both. At The Donkey’s Tail exhibition in March 1912, Goncharova displayed several pieces with a marked attention to religious themes. One of these works, The Evangelists, was actually confiscated by a censor for being blasphemous. Though the painting looks tame to the contemporary eye, it melds the religious style of icons with rebellious Cubo-Futurist elements like bold color and blocked abstraction. Moreover, it was displayed at an exhibit called The Donkey’s Tail, which was interpreted as an insult to propriety.

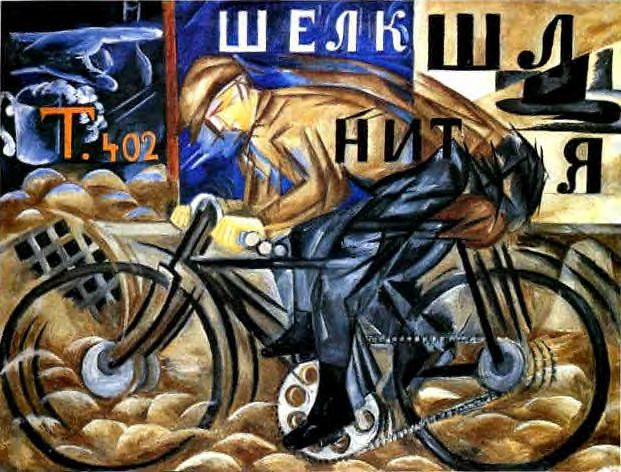

At the Target exhibition held in 1913, Larionov fully expressed his Rayonnist ideas, which sought to represent the feeling and essence of an object by painting its emitted rays, rather than its literal form. Displayed at Target were the extrapolated, perceived, and, to a degree, spiritually-understood spaces between viewer and object. The Rayonnist works of Goncharova still for the most part depicted distinguishable objects or people, while Larionov’s tended towards pure abstraction. Her works in this style, such as The Green and Yellow Forest, Cats, and The Cyclist all capture the energy of their subjects by emphatically dramatizing their lines and angular movements.

Natalia Goncharova was more than just a major artist of the avant-garde – she was also a controversial, unique and highly visible personality in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Her antics drew both praise and derision. The fact that she lived with Larionov, according to Russian art historian John Bowlt, “stirred the indignation of both church and public” (45). She often wore pants and other traditionally-male attire. She published manifestos and in 1913 and 1914 she held her own one-woman exhibitions in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. For these and other behaviors she has been sometimes remembered as “histrionic.” But if Goncharova was histrionic, then her numerous comrades were certainly guilty of it as well. The Russian Futurists as a group were innovative and bold not only on canvas: they brought art into their daily lives. In fact, they traversed the ordinary bounds of art, their work melding indistinguishably into the behaviors of their daily lives. They painted symbols on their faces, usually hieroglyphics or flowers. Goncharova would sometimes appear topless in public, with symbols painted on her body. In a sense, their use of odd, possibly meaningless symbols united the masses with the past Symbolist aesthetic. In taking it away from the intelligentsia, they harshened and blunted its imagery.

Of course Goncharova’s creative genius, combined with her gender, made her a focal point more innately provocative of attention than any of her fellow rebels. According to Bowlt, “in private relations and behavior, Goncharova enjoyed a license that only actresses and gypsies were permitted, and perhaps because of this dubious social reputation rather than as the result of any apparent innuendos in her paintings, she was said to traverse the ‘boundary of decency’ and to ‘hurt your eyes’” (45).

Diaghilev, with whom Goncharova worked on several projects, had this to say of his protégé:

“The most celebrated of these advanced painters is a woman. [. . .] This woman has all Saint Petersburg and all Moscow at her feet. And you will be interested to know that she has imitators not only of her paintings but of her person. She has started a fashion of nightdress-frocks in black and white, blue and orange. But that is nothing. She has painted flowers on her face. And soon the nobility and Bohemia will be driving out in sledges, with horses and houses drawn and painted on their cheeks, foreheads and necks” (qtd. in Chamot 173).

In 1913, she and Larionov opened and closed two cabarets: the Pink Lantern cabaret, which only saw a few performances, and, for a brief period in November, the Tavern of the 13. Both cabarets featured an intense degree of audience participation, featured improvisational dance and a heavy dose of their pseudo-Symbolism.

A performance at the Tavern on the 13 was actually made into a film entitled Drama in the Futurists’ Cabaret No. 13. The short movie was directed my Vladimir Kasianov and it “attracted full houses and … scandals” (qtd. in Bowlt 48). No intact version of the film remains. There is only a still frame of a man and woman, probably Larionov and Goncharova, the woman covered in symbols and partially bare-chested. The film began with a poetry reading and improvisational tango and ended with a “‘Futuredance of death,’ during which one partner must kill the other” (qtd. in Bowlt 48).

In 1914 Larionov and Goncharova left Russia to do stage design with Diaghilev in Paris. Goncharova’s brightly-colored designs strongly evoked Russian folk art, but also held true to her Cubo-Futurist aesthetics. She first worked on Diaghilev’s 1914 production of Le Coq D’Or, then in 1915 she followed the Ballets Russes to Lausanne, Switzerland, where she designed for Liturgie.

Goncharova and Larionov also leant their talents to at least four high-profile charity balls in Paris.These were the Grand Bal des Artists, (alternately: the Grand Bal Travesti Transmental) in 1923, the Bal Banal in 1924, the Bal Olympique (alternately: the Vrai Bal Sportif), also in 1924, and the Grand Ourse Bal in 1925.Goncharova incorporated tribal masks, Russian folk art and mythology into the costume designs, interiors and publicity materials for these events.

In 1923 she designed for Les Noces, and in 1926 she reworked the original 1910 designs for a new production of The Firebird. In 1937, Goncharova created new designs Le Coq d’Or by commission of Convent Garden London. She did the same for Cinderella in 1938. Even during the Second World War she continued working, designing ten South African ballets for Boris Kniaseff. Following the war, she split her time between Paris and London, designing for the stage in both cities. Despite having crippling arthritis, she began painting again briefly in the fifties, inspired by the USSR’s space program. In 1961, a year before her death and suffering badly from arthritis, she redesigned The Firebird yet again for the Royal Ballet.