Mikhail Bulgakov wrote Master and Margarita between 1928 and 1940, during some of the most severe years of Soviet censorship. During this period authors and poets—the individuals most well equipped to transcend propaganda and recognize societal flaws—were prohibited from doing so at threat of death or imprisonment. However, while direct criticism was impossible, indirect was not. Authors, such as Bulgakov, found methods of conveying searing political commentary through allegory, subtlety, and myth.

Filling Master and Margarita with satire and subtle digs, Bulgakov uses comedy and creativity as a vessel to communicate a deeply earnest moral about the role of personal cowardice in Soviet corruption. A throughline in the novel, Bulgakov continuously reaffirms that individuals are responsible for their own choices, even if they live in an unjust society. He argues, if citizens had been guided by bravery and sincerity rather than self-preservation, then Soviet society would not have been able to deteriorate as it did. Bulgakov writes one of the titular characters, the Master, to be the thematic crux of the novel. Personifying truth in an age of censorship and deceit, his character arch is imbued with the full significance of Bulgakov’s message.

Only featured in eleven of the thirty-two chapters, the Master is a title character, but rarely present in the novel. Performing few actions and delivering infrequent dialogue, his most notable and character-defining moments are relayed in backstory, not within either of the two timelines that unfold across the novel. As such, the Master is best analyzed through his relationships with other characters. An idol to Margarita, a mentor to Ivan the Homeless, and a god to Pilate, the Master has considerable impact on the lives of others.

Margarita—young, beautiful, and rich—possesses every material good. Yet, until meeting the Master, she lives a life devoid of meaning. Close to suicide, Margarita seemingly needs divine intervention to save her life. Then enters the Master. Bulgakov depicts Margarita’s meeting with the Master as a fateful, even preordained event; after their initial interaction, Margarita “insisted that… [they] had, of course, loved each other for a long, long time, without knowing each other” (138). By coloring their relationship with this deep, almost spiritual connotation, Bulgakov establishes the Master as a Christ-like savior. More obviously, Margarita’s insistence of calling her love “Master” lends to his characterization as a spiritual leader and hers as his disciple.

Ivan the Homeless begins his story as a tool of the state. Tasked to write an anti-religious poem, young Ivan unquestioningly drafts the piece. Yet, his ignorance stops him from succeeding at even this minor undertaking. Though he proudly proclaims his atheist stance, Ivan’s lack of theological knowledge renders him incapable of producing a convincing denunciation of Christ. Not fueled by passion, nor by educated thought, Ivan’s poems are repackaged state propaganda. But through his connection with the Master, Ivan undergoes great growth. In chapter thirteen, one short conversation with the Master leads Ivan to accepting the failures of his poetry, calling it “atrocious” and promising to write no more (131). Ivan recognizes himself as an “ignorant man” and is imbued with the desire for knowledge (133). At the end of Ivan’s conversation with the Master, he begs, “Tell me, what happened afterwards with Yeshua and Pilate,” completing his transformation from an unthinking sycophant to an engaged and curious seeker of truth (147).

Pontius Pilate, the “cruel fifth procurator of Judea,” experiences a change of heart even more drastic than Ivan the Homeless. (396). A prideful and uncaring man, he boasts of his reputation as a “fierce monster” and guiltlessly inflicts brutal beatings (16). His interactions with the sinless Yeshua, however, force Pilate to confront his own conscience. After sentencing the innocent man to death, he is haunted by his iniquities. Yet, despite Yeshua’s power to break through Pilate’s hardened heart, even he cannot redeem the selfish bureaucrat. The Master, as the author of Pilate’s story, solely holds the power to release him from his guilt. In chapter thirty-two, the Master reverses Pilate’s fate and saves him from an eternity of suffering with only the sound of his voice, simply proclaiming, “You’re free!” (382).

From the immense influence that he has on other characters, one would think that the Master is a holy, fearless, and powerful being. Much to the contrary, the Master is a defeated coward. After his novel met criticism and undeserved animosity, the Master was unable to face life. Overwhelmed by the harsh realities of an unjust system, he checked himself into a mental hospital to silently wait out the rest of his days in hiding. Not he, but his love, Margarita, was the loyal champion for truth. Unlike the Master, she refused to forsake what she believed to be true, authentic art. Likewise, not he, but Ivan the Homeless, once a puppet of Massolit, devoted the rest of his life to the pursuit of knowledge—he became a professor of history and philosophy. And not he, but Pilate, once a leading member of a corrupt system, became obsessed with the idea that the innocent not be punished, and that cowardice not be nurtured.

The Master is granted such important roles as Margarita’s rescuer, Ivan’s teacher and Pilate’s redeemer because of his symbolic role as Truth. As the author of a dissident work, the Master is a representation of authentic art in an unaccepting world. Although he is unable to overcome the cruelties of corruption and censorship, he still has purpose and impact. Like the real Soviet authors who were forced to communicate their ideas through samizdat (self-publishing) and the Master has meaning not through worldly acclaim or recognition, but through those he inspires.

You Might Also Like

Mikhail Bulgakov, Master and Margarita, and Truth in the USSR.

Mikhail Bulgakov wrote Master and Margarita between 1928 and 1940, during some of the most severe years of Soviet censorship. During this period authors and poets—the individuals most well equipped to transcend propaganda and recognize societal flaws—were prohibited from doing so at threat of death or imprisonment. However, while direct criticism was impossible, indirect was […]

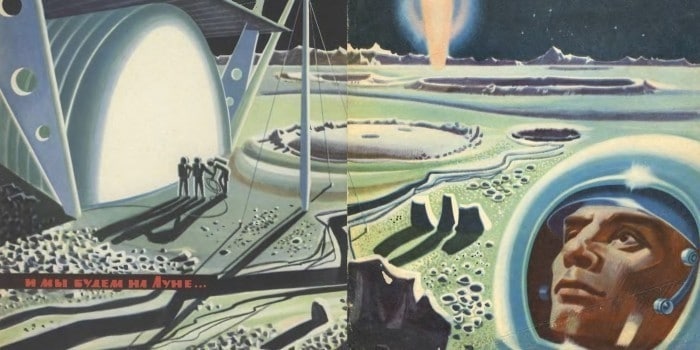

Science Fiction and Fantasy From Behind the Iron Curtain

Science fiction/fantasy, often shorthanded to SFF, is a genre of media concerned with supernatural, fantastical, or other elements beyond our current technological capabilities. Although its roots run deep, borrowing inspiration and elements present in The Odyssey or 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, SFF truly came into its own after the Industrial Revolution. It was a […]

The Control of Semantic Space: Bulgakov’s Challenge of the Stalinist Vision

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (1967) and Heart of a Dog (1925) are among the most provocative works which challenge the Stalinist vision of controlled cultural space. His stories illustrate in detail how space forms society and influences cultural development. Through his prose, Bulgakov exhibits a unique understanding that Stalinism maintained control of society by controlling Soviet space. His […]

‘Irrational’ Rebellions Against Socialist Realism: Czech and Russian Variations on the Legend of Faust

During the 20th century, communist parties assumed state power in Russia and a number of Central and East European countries. The communist leadership of these nations imposed socialist realism as official doctrine governing artistic production. The ruling parties’ ideology emphasized human rationality as the means for creating a well-ordered socialist society, which would be free of […]