The Dostoevsky Memorial Apartment Museum at 5/2 Kuzneckny Pereulok in St. Petersburg is dedicated to drawing a picture of the great Russian writer as a person with a focus on his work habits, on his concerns, and particularly on his family life. Even discussion of his greatest novels is presented within the context of telling us more about his family, which was at the center of Dostoevsky’s universe.

The museum is located at Kuznechny Perulok, a few minutes’ walk from the landmark Church of the Vladimir Icon, which once counted Dostoevsky and his family among its congregation. In 1846, Dostoevsky briefly rented an apartment in the building and, in 1878, he returned to the same building with his family, where they resided until his death in 1881.

Similar to many memorial apartments in St. Petersburg, the available audio guide (in Russian, English, French, Italian, Spanish, and Chinese) is highly recommended. Although each room has its own small poster filled with information, it is minimal compared to the information that the audio guide will provide.

Upon entry, the audio guide informs you of the unique history of the museum itself. The reconstruction of Dostoevsky’s Memorial Apartment did not begin until the late 1960s. The Soviet authorities generally did not promote Dostoevsky due to his early radical anti-authoritarian politics and his religious nationalism. Thus, his former apartment was initially used as a communal apartment. Only in 1956 was a memorial plaque was erected on the exterior of the Kuznechy building. The guide, interestingly, says this happened due to Dostoevsky’s international popularity, and does not mention that this was shortly after Stalin’s death and during the early years of the Khrushchev Thaw, which most likely played into the changing politics surrounding the writer. The museum, then, is likely balancing the two historical figures, both of which continue to be held in high esteem by a significant number of Russians.

In 1968, the apartment was renovated to restore it to its condition as depicted in Dostoevsky’s journal entries and the archived floor plans from the time. On November 11, 1971, on what would have been Dostoevsky’s 150th birthday, the memorial apartment opened in his native city.

Since then, the government has worked hard to maintain this cultural landmark. Both the exterior and the interior of the building are well kept. The apartment is warmly decorated with colorful Russian-print wallpaper authentic to the time period and lavish wooden furniture. Although light fixtures hang only above certain important display pieces, the windows allow for plenty of natural light to brighten each room.

While the home is welcoming, it also has a dark history, as Dostoevsky’s family moved into the apartment during a sorrow-filled time in their lives, shortly after Dostoevsky’s young son had died. The home then, was supposed to serve as a place of rejuvenation and inspiration for the family. At this point it is clear that the museum, via the audio guide, seeks to highlight Dostoevsky’s close relationship with his children and wife by exploring the apartment where he spent his final years.

Dostoevsky had four children with his wife Anna Grigorevna. The pair’s first child, Sonya, was born in 1868 but died three months later. Lyubov and Fyodor were born in 1866 and 1871, respectively. In 1875, Dostoevsky’s last child, Alexey, was born. In the spring of 1878, however, shortly before moving to their St Petersburg apartment, Alexey passed away after an epileptic fit. The guide informs that epilepsy was a condition which Dostoevsky himself suffered.

This death affected Dostoevsky’s life and literature greatly, as he was particularly close to his young son. His sorrow is further expressed in a passage that the audio guide reads from Anna’s memoir, where she writes that Dostoevsky was “terribly” hurt by this loss as “he especially loved Alyosha, almost painful love, as if foreseeing that he would soon be lost.” The heart breaking death of his young son, the audio guide argues, inspired Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov which he wrote in the memorial apartment between 1978 and 1881. Dostoevsky’s own pain is reflected in the character Snegiryov, who suffers greatly after the death of his child.

The story of Dostoevsky’s loss is sharply juxtaposed with the room it is presented in: the children’s former playroom, filled with small toys and pictures of Dostoevsky’s two remaining children. The viewer is left with a bittersweet feeling, one that Dostoevsky himself likely felt.

The audio guide further describes Dostoevsky as a family man and loving father. For Dostoevsky, without children life would have no meaning. As evidence, the guide tells us that when he travelled away from his family he would write letters to his wife Anna, and always begin by inquiring about their children and then further delve into his fears about their respective futures. The museum, then, seeks to inform the viewer that to Dostoevsky, being a father was his most important role in life.

As you enter a small, brightly colored kitchen, the guide tells of the family’s nightly gatherings. In the evenings, at 6 pm sharp, Dostoevsky yevsky would make sure to always dine with his family to discuss their lives and current events. Furthermore, at night, before his children went to sleep, he read his children works of Russian and European literature that he loved as a child by authors such as Pushkin, Gogol, Dickens, Hoffmann, Schiller, and Hugo.

Anna’s room is that of a professional woman whose life was absorbed in writing and typing. The focal point is an elegant wooden desk covered in papers in her handwriting. According to the audio guide, her entire life was devoted to her husband, and she served as his secretary and stenographer. She took care of all of Dostoevsky’s business, including overseeing the publication of his novels, control of the family finances, as well as bringing up the children. Dostoevsky’s appreciation, and love, of his wife can be seen his dedication of his last published work, The Brothers Karamazov, to Anna.

Even after Dostoevsky’s death in 1880, Anna dedicated herself to preserving her husband’s legacy. For the rest of her life she collected materials about her husband’s life and worked to further publish and spread his works. These materials, in fact, became the basis of the Dostoyevsky Study which opened in 1901 in the Moscow Historical Museum. In 1928, during the “Silver Age” under the USSR and before the onset of widespread censorship, this collection became the foundation of the newly opened Dostoyevsky Museum in Moscow. Interestingly, during the Soviet era, this museum remained open.

The final room of Dostoyevsky’s memorial apartment is his office. In Dostoyevsky’s lifetime this room rarely saw any foot-traffic other than Dostoyevsky’s; it was his private working space. For Dostoyevsky, absolute silence was necessary for him to write, and thus he would work between 11 pm to 6 am. Similar to the other rooms of the apartment, the walls are covered in dark Russian-print wallpaper, and dark wood furniture fills the room. The focus is Dostoyevsky’s large desk where he wrote The Brothers Karamazov, as well as the articles for the latest issue of The Writer’s Diary, and prepared his famous Pushkin speech as he considered the author his teacher in both literary works and his worldview.

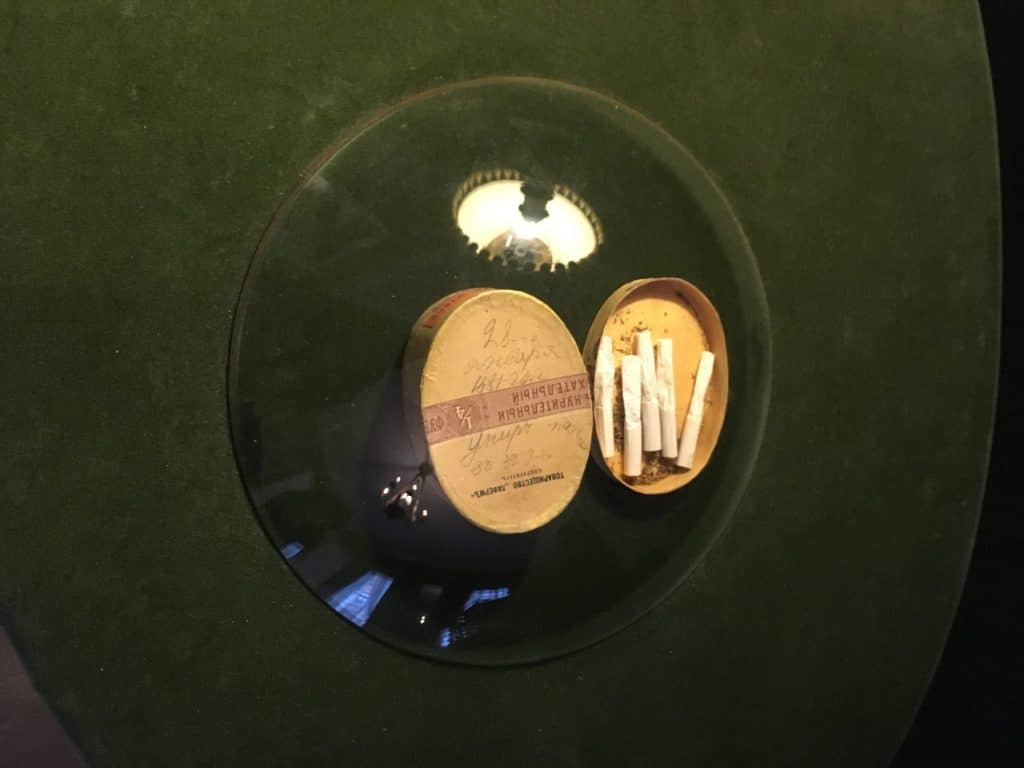

In this office, where Dostoyevsky spent many a night writing, he passed away. Today, on the table, sits a Laferme tabacco box where there is still an inscription made by his daughter, written on the day of his death which reads, “28 января, 1881 умиръ папа” which translates to: “January 28, 1881, Papa died.” There is also a clock displayed on the table near the window that once belonged to Dostoevsky’s younger brother, Andrey. It is stopped to continually display the day and hour of Dostoevsky’s death: January 28, 1881, at 8 pm.

The fee for the memorial apartment also covers the entrance into Dostoyevsky’s Literary Exposition. This room houses temporary expositions that are changed regularly. Currently, it is set up to literally interpret a favorite biblical quote of Dostoyevsky: “И свет во тьме светит, и тьма не объяла его.” This quote is translated by the guide into an older style of English speech: “and the light shineth in the darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.” The room has no overhead lighting and the walls are painted black, the only thing in light are photographs, portraits of Dostoyevsky, his friends, and places he visited and lived, as well as documents, letters, and manuscripts related to Dostoyevsky. The only natural light comes from a single open window that overlooks Vladimirskaya, Dostoyevsky’s beloved church. This exposition room brilliantly juxtaposes the unchanging memorial apartment with something fresh and constantly changing to continually reinterpret Dostoyevsky’s literature in a modern context.

Dostoyevsky played a vital role in contributing to the Russian literary canon in his lifetime. Although he achieved notoriety in his lifetime, namely in the late 1870s, it was after his death that his literature became widespread. Today, Dostoyevsky’s long novels are still read as some of the most important literature to be written in Russia. However, Dostoyevsky was also a man who championed traits that are still championed by many in Russia today: a dedication to his family, his work, and his philosophy. Dostoyevsky is thus an important figure in St. Petersburg’s cultural history, and will continue to be celebrated and remembered through his literature and life.

You Might Also Like

(includes current article)

The Dostoevsky Memorial Apartment Museum in St. Petersburg

The Dostoevsky Memorial Apartment Museum at 5/2 Kuzneckny Pereulok in St. Petersburg is dedicated to drawing a picture of the great Russian writer as a person with a focus on his work habits, on his concerns, and particularly on his family life. Even discussion of his greatest novels is presented within the context of telling […]

Crime and Publishing: How Dostoevskii Changed the British Murder

A few words on this book: Described by the sixteenth-century English poet George Turbervile as “a people passing rude, to vices vile inclin’d,” the Russians waited some three centuries before their subsequent cultural achievements—in music, art and particularly literature—achieved widespread recognition in Britain. The essays in this stimulating collection attest to the scope and variety […]

The Hero of Cana: Alyosha’s Ode to Joy in The Brothers Karamazov

Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov opens with a particularly unsatisfying note. The fictional narrator declares in his “From the Author” that the hero of the book is Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov. Quickly following this declaration is a confession: “To me he is noteworthy, but I decidedly doubt that I shall succeed in proving it to the reader” (Dostoevsky 3). […]

Suicide as a Final Reconciliation of Conflicting Identities in The Brothers Karamazov

The function of violent death is complex in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: it serves as the driving focus of the work, calls into question the many characters’ agency and morality, and provides a forceful resolution. At the forefront of the novel is the murder of Fyodor Pavlovich by one of his sons. Parricide is the […]

Rational Perversions of Love in The Brothers Karamazov: Spiritually Fruitless, yet Thematically Useful

In The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky spends countless pages elucidating his ideal of love. Among his many characters, he offers complex portraits of two intriguing individuals, whose love does not quite fit his definition of this ideal. The Grand Inquisitor and, by extension, his creator Ivan, are often seen as simply hyper-rational characters who reject God’s […]