As you approach the New Tretyakov building, the cold February wind numbing your face, you look up and can’t help feeling dwarfed by the large modern-brutalist structure and the thought of the agglomeration of a century’s worth of artwork inside. Once you get past the imposing exterior, however, you are welcomed by a spacious and warmly lit interior and make yourself a guest of the past and its cultural heritage.

The New Tretyakov Gallery is a well-known addition to the famous original museum and boasts an impressive collection of 20th Century Russian art, acclaimed the world over for groundbreaking advances in objective-and non-objective art—cubism, neo-primitivism—the pinnacles of avant-garde, as well as stately works of art in the Soviet Realist style. The exhibited works closely follow the course of Russian history over the past century, reflecting the currents of excitement, turbulence, repression and opposition that it contained.

I visited the gallery on an SRAS-arranged tour with a knowledgeable guide from Bridge to Moscow. The experience opened my eyes to how much art can truly reveal about the societal climate of an era.

In Russia, the 20th Century began with a burst of colorful avant-garde art produced by artists like Kandinsky, Goncharova, and Chagall, who pushed the boundaries of their time and produced a new level of artistic innovation. This was an exciting time for the creative class; artists openly expressed themselves without censors for the first time in Russian history. They also formed unions like Jack of Diamonds and were an influential social force. This period was characterized by great excitement, optimism, trepidation and suspicion—the perspectives were as varied as the art movements. The Russian Revolution was the defining historical event in the context of early 20th century artwork. In fact, the entirety of Russian history can be split into the pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary periods.

The painting above, for example, captures the enthusiasm preceding the revolution. The bell tower is distorted in an eruption of bright, happy colors, while a rainbow gradient in the background creates a synesthetic effect in which you can almost hear the church bells ringing, the sound flowing out in circular waves. This painting is very characteristic of Lentulov’s colorful and chaotic style, which in turn may have been inspired by the unpredictable state of affairs at the time.

Not everyone had a bright outlook about the revolution, however. As our guide explained, the background in this painting features a typical view of the Russian countryside but is cast in dark and foreboding tones, symbolizing the turbulence experienced during the revolution. It was an especially uncomfortable time for Chagall, who had to move to the outskirts of Moscow and lived through periods of hunger after the First World War ended in 1918. The only source of solace is an angel hovering over Chagall and his dearly beloved wife, Bella, and if you look closely at Bella’s cheek you can see the figure of a small person, representing their first child, Ida.

After the end of revolution, there were many futuristic, even utopian, projects planned with the aim of bringing the newly established Soviet Union to great heights. One ambitious artist and architect was Vladimir Tatlin, active during the avant-garde movement of the 1920s. This work, commonly known as Tatlin’s Tower, is a model for a radically sophisticated building that never saw construction. It was supposed to be the central feature of the St. Petersburg skyline, standing taller than the Eiffel Tower and containing several suspended structures rotating at yearly, monthly, daily, and hourly intervals in order of ascension. Unfortunately, such an architectural feat was impractical in the face of housing and steel shortages that followed the revolution.

As the 1930s came to pass, avant-garde art fell out of favor with Soviet officials. State policy brought back powerful censors and allowed only positive depictions of Soviet life in a realistic style, as other forms of expression were viewed as bourgeois. Artists either fled or adapted to the new standards, giving rise to the artistic movement known as Socialist Realism. There may not have been as much creative innovation during this period, but state-sanctioned art was nonetheless steeped in talent and produced memorable works. In this painting, an intentionally illuminated Stalin is seen with one of his highest-ranking military officers, both looking especially dignified.

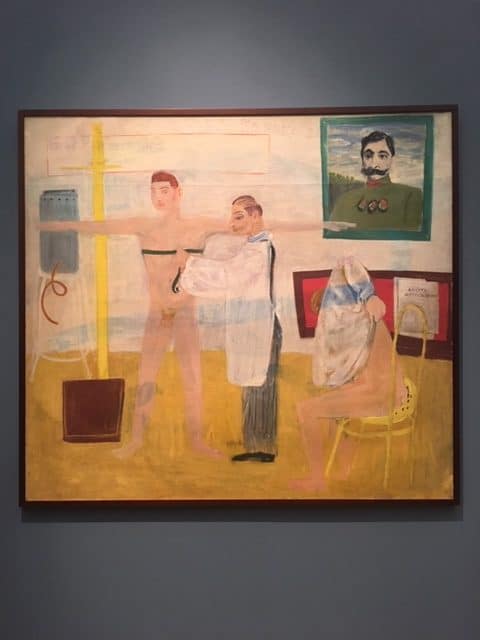

Artists that carried on in defiance of the new policies had to do so in secrecy. Georgy Rublyov, who had roots in the avant-garde movement, created and organized exhibitions for official Soviet art but also continued to paint in a neo-primitivist style in his own time. This particular painting was only found after Rublyov’s death in 1975. Discovery of the painting a few decades before then may have resulted in a much sooner date of death for Rublyov, as the portrait of Stalin in the background is far from flattering.

The amount of influence that history has on art, even on abstract pieces that seem fairly removed from reality, is fascinating. Going to the New Tretyakov Gallery with a guided tour not only revealed the specific context behind these paintings, but also allowed me to gain a greater appreciation of the works I saw and the artists’ efforts in creating them. I would definitely recommend this experience to anyone interested in Russian history and contemporary art.

New Tretyakov Gallery

SRAS-arranged cultural event for spring, 2019 Moscow programs