In the remote Nukus Museum of Uzbekistan, a vast collection of banned Russian avant-garde art has been preserved for decades. The museum and its collection were founded by Igor Savitsky, a Soviet artist who defied censors to rescue and safeguard these works. His success was also made possible by the unique geography and history of Karakalpakstan, the region where the museum is located. After the fall of the USSR, Savitsky’s hand-picked successor Marinika Babanazarova had to continue to fight for the collection’s survival and international recognition. Today, Uzbekistan is going through a new period of political reform, economic growth, and opening to the outside world. Nukus could finally have a chance for a stable collection and its own growth and development.

Who was Savitsky?

About half a century ago, near the dusty shores of the retreating Aral Sea, Communist Party officials visited the Museum of Igor Savitsky. Savitsky, affectionately called “Junkman” by his friends and associates, was an artist. Under the nose of State officials (and sometimes with their funds), he was amassing a collection of over eighty thousand banned Russian avant-garde artifacts. He owned but one suit, which he wore only during inspections. When the officials saw The Bull (Fascism Advances), a painting by Vladimir Lysenko, hanging in the museum, they immediately declared the painting anti-Soviet and ordered its removal. As founder, director, and protector of the museum, Savitsky instantly complied.

Once the inspectors left, the director returned both his suit and The Bull to their rightful places. For now, his collection was safe: Nukus, the capital city of Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic located inside western Uzbekistan, was far away from the Party nucleus. Inspections were rare.

Savitsky traveled the USSR, visiting the homes of deceased or disappeared artists to relieve their spouses of any forbidden art, at once removing what might further incriminate the family from their home and yet safeguarding the legacy of their departed member. From the tens of thousands of artifacts Savitsky collected, Lysenko’s Bull prevailed as the museum’s unofficial mascot. The long-gone Party inspectors had not appreciated the painting in part because of the unrealistic presentation of the bull but also because the bull is so aggressive. It is known by a second name (which some historians believe that Savitsky actually made up), Facism Advances. However, art critics consider The Bull’s shotgun eyes symbolic–prophetic, even, of the Stalinist repression that branded the early 1930’s.

Savitsky grew up during the height of the avant-garde movement. Born in 1915 to an aristocratic family in Kyiv, he received a good education, travelled abroad, and learned to speak fluent French. In 1934, he began his secondary education at the Moscow Institute of Printing and, in 1941, continued his studies in the Moscow State Art Institute. Both institutions specialized in socialist realism. Exempt from the draft due to illness, in 1942 Savitsky and other members of the Institute evacuated to Samarkand, Uzbekistan’s second largest city. WWII was raging in Europe at the time and had just recently come to the USSR.

In Uzbekistan, he quickly became enchanted by the people, culture, and landscape of Central Asia. Although Savitsky transferred back to Moscow after two years in Samarkand, he enthusiastically returned at the invitation of T.A. Zhdanko to work with the Khorezm Archaeological and Ethnographic Expedition in 1950. He travelled extensively through Khorezm and Karakalpakstan, around where his future museum would reside. Savitsky created his own art and also collected Karakalpak folk and applied art for museums in Moscow and St. Petersburg. He soon relinquished his flat and career in downtown Moscow and moved to Nukus fulltime.

Savitsky’s deep respect for Central Asia’s art and traditions earned him the elusive trust of local authorities. Karakalpakstan, a small Turkic nation of nomads, farmers, and fishermen, is nestled within western Uzbekistan: the intersection of Russia, the Middle East, and Asia. The Expedition, commissioned to sketch the ruins of an early civilization on the edge of the Aral Sea, employed the artist until 1957, at which point he left to work at a research institute and develop his then-private collection of artifacts.

Savitsky tasked himself with the preservation of culturally and historically significant Soviet art. To the best of his ability, he compiled a comprehensive collection of each artist he encountered to showcase their career-long trajectory. Some art he purchased with his own capital, other pieces he wrote I.O.U.’s for – thousands of these were still outstanding at the time of his death. Many were resolved by the newly independent Uzbek state in 1992, although this process was aided by the fact that inflation had degraded the value of the IOUs significantly.

In 1966, Savitsky convinced the local authorities that Nukus needed a museum of its own to display traditional Karakalpak art. He was then able to use his status as a museum worker to surreptitiously gather forbidden art for museum purposes, often using state funds to do so. Once, after discovering a series of sketches by Nadezhda Borovaya, an artist who smuggled depictions of her daily life out of the Temnikov Gulag, Savitsky persuaded party officials that her art illustrated Nazi concentration camps. He thus secured state funds to purchase the banned art.

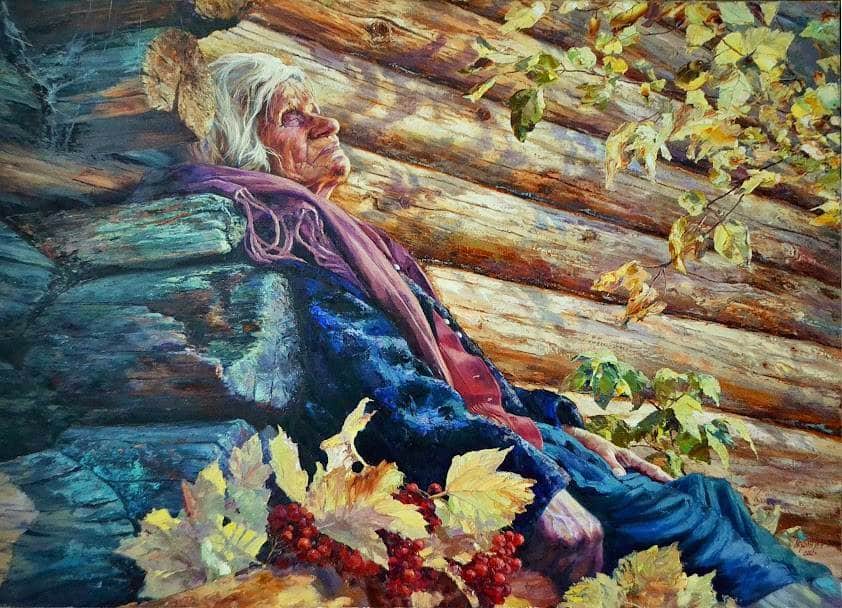

Savitsky continued his activities until he fell ill in the 1980s. Amazingly, he always managed to stay just under the radar and was never himself persecuted in his lifetime. He died in 1984 in a Moscow hospital. Today he is recognized as a trailblazing activist collector and an innovative museum director and curator. He is also known as a remarkable art restorer and conservationist, preserving paintings in the harsh and arid region and often having to restore works that had been hastily hidden from authorities. He advanced knowledge of traditional Karakalpak arts and culture, himself painted dozens of landscapes of the desolate land that he loved, and was a teacher sought out by many who wanted to learn how he managed to achieve so much.

What and Where is Karakalpakstan?

The full name of the Nukus Museum is “The State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Karakalpakstan named for I.V. Savitsky.” Its common short name, Nukus, is taken from the city it is located in, the capital of the Republic of Karakalpakstan.

The Karakalpak people, a Turkic ethnic group, first appear in historical records around the 16th century. Their specific origins remain debated, but they were likely once part of the Kazakh Khanate, and compelled to migrate west due to internal political conflict in the 18th century. They became nomadic fishers and herders along the Amu Darya River and Aral Sea.

Their culture is heavily defined by their language, Karakalpak, which belongs to the Kipchak branch of the Turkic family, similar to Kazakh. Traditional sung oral epics are integral to the region’s cultural identity. Since independence, they have regained significance and appear not only at festivals devoted to them, but at private weddings and state concerts as well.

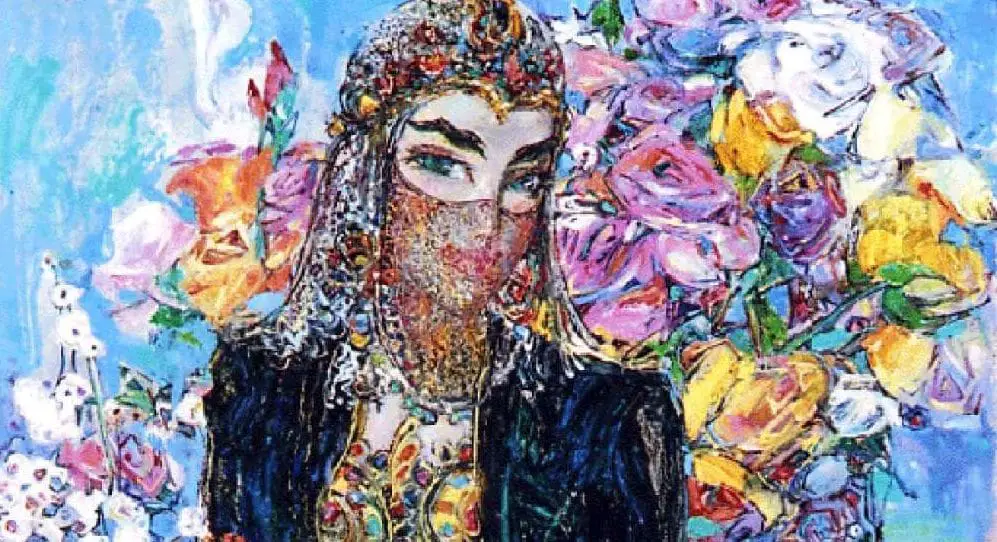

The region’s artisans are celebrated for their distinctive pottery, intricate textiles, and particularly for their elaborate embroidery. Many examples of these applied arts can be seen at the Nukus Museum.

The arrival of the Soviets greatly changed life in Karakalpakstan. First, the Karakalpaks were forced to develop settled industry and agriculture, giving up their nomadism. A bioweapons lab was built in the desert in 1948 and Karakalpakstan became a “closed region” with high barriers to entry.

Perhaps most importantly, Soviet agricultural policy caused one of the greatest man-made environmental disasters in history.

When the American Civil War threw global cotton markets into disarray, the Tsar began growing the crop in Karakalpakstan to ensure a supply for the Russian military. Stalin later called for total self-sufficiency, massively expanding the plantations and their irrigation projects that drew from the Aral Sea’s only tributaries. Its water source choked, the sea dried. Today, a mere tenth of the Aral’s volume remains.

The sea and its once abundant fish were an integral part of the local economy. Major dust storms, which previously occurred once every five years, now occur up to ten times a year. Between economic collapse and environmental devastation, the population plummeted. Those that were left were impoverished.

The Karakalpaks’ distinct identity, their many legitimate reasons to dislike and distrust policy makers in Moscow, and their desolate, closed region all likely fed into the success of the Nukus Museum. Savitsky, an outsider who was genuinely knowledgeable and excited about Karakalpak culture, was able to gain to the complete trust of the local authorities who, in turn, were more than willing to protect him. The region’s isolation meant that it was often overlooked by the central authority in Moscow.

While Savitsky’s unique charm and his ability to negotiate the Soviet system was pivotal in creating the Nukus Museum, so too was the unique history and geography of the surrounding region of Karakalpakstan.

Who Was Lysenko?

Though historians have constructed a patchwork of the painter’s life, remarkably little is certain about Lysenko. Today, he’s most often recognized as Vladimir, but some records paint him as Yevgeny Lysenko. He first visited Uzbekistan’s capital, Tashkent, in either 1918 or 1919. From 1925 to 1929, he studied under Kazimir Malevich, pioneer of the avant-garde suprematist movement. Malevich’s records state his identity as Vasili Alexandrovich Lysenko, born in the Bryansk province. Lysenko returned to Tashkent without completing his studies and later presented a large number of his canvases at the first Republican Exhibition of the Fine Art Workers in Uzbekistan, from where he traveled through the Caucasus, Pamir, and the Khorezm oasis. Rather than a livelihood, the artist’s work led only to hardship. In 1935, Lysenko was arrested, denounced as a formalist, and sentenced to six years in a mental hospital. Despite that, the artist again presented his work at exhibitions in Novosibirsk and Krasnodar during the latter half of the 1940’s. By 1951 the painter returned to Tashkent, and the State declared him “rehabilitated” two years later. He spent the final years of his life semi-paralyzed and seriously ill in the home of his sister, where he died sometime during the mid-to-late 1950’s.

Nothing of the artist Lysenko would remain without Igor Savitsky. Frightened by the State’s attitude towards the arts, the museum director collected in earnest during the early 1960’s. He discovered four canvases discarded in Lysenko’s attic, so hapless that in lieu of a rag one was used to plug the leaking roof. The Junkman restored them at the Nukus Museum, under whose protection they remain today.

What Was the Avant-Garde?

The Nukus Museum houses the world’s second largest collection of Russian avant-garde art. Rather than a specific style, avant-garde refers to a period during which many modernist subcurrents flowed. The phrase is derived from French military terminology and roughly translates to “advance guard.” Soldiers in the advance guard march ahead of the main battalion–they’re scouts and trailblazers; the most vulnerable and the first to die. The artistic movement, which emerged around 1890, unfolded through the extensive flow of art and artists between Paris and Moscow. Russian avant-garde developed alongside its Western contemporaries until the October Revolution, at which point it became an extension of the State. Artists of the avant-garde saw, through art, a way to make a revolutionary break with the old society.

Lysenko studied under Kazmir Malevich at the Institute of Artistic Culture, one of two art academies established by Vladimir Lenin. As the movement’s most influential patron, Lenin’s institutes offered artists such as Malevich and Vasili Kandinsky space to debate freely the ideologies that shaped avant-garde. The abstract images they produced, which involved precise geometry and emphasized proportion and space, challenged commonplace notions of art and reality. During this period, both movement and revolution worked harmoniously to forge a revolutionary society. Suddenly, after suffering two strokes during 1922, Lenin retreated to his dacha outside of Moscow. In his absence, Joseph Stalin began to consolidate power and, once Lenin died in January 1924, assumed his title and responsibilities.

The State’s preference in art shifted along with the regime. Unlike Lenin, Stalin considered the avant-garde bourgeois, instead preferring the more straight-forward and more easily understood realism. Stalin’s preferences were eventually institutionalized in what became known as socialist realism: characterized by the glorified, realistic portrayal of communist values. By 1930, about the time Lysenko returned to Tashkent, Stalin dissolved both of Lenin’s institutes and forced the movement underground. Two years later, the Party took control of artists’ unions and officially imposed socialist realism one year after that. Stalin effectively constrained art to populist, realist, and easily understood iterations of the New Soviet Man and the accomplishments of the first and second five-year plans.

During Stalin’s reign, “formalism” came to be used to decry nearly any form of art that deviated from the norm and was often used in political struggles between artists to denounce rivals. The State fought an escalating campaign to completely eradicate the genre until Stalin’s death in 1953. Savitsky played a major role in preserving that entire generation of Soviet art.

The Museum and Collection Under Babanazarova

Savitsky collected until his death in 1984. During his final days, the collector named Marinika Babanazarova as his successor. The daughter of a close friend, Babanazarova jealously protected the collection for thirty-one years. In January 1998, a New York Times article about the museum prompted 85 artists and scholars to charter a flight from New York to Nukus solely to satiate their curiosity. Eager to own a piece of history, some of the visitors offered massive sums of money in exchange for original artwork, but Babanazarova refused, fearing that selling even one piece would give way to a massive government auction.

In 2003, the Nukus Museum, which began as a modest one-story building without air conditioning, was moved into a new three-story complex. Despite the expansion, the museum can only display about 3% of its collection, which boasts over 82,000 objects ranging from Khorezm antiques and Karakalpak folk artifacts to Uzbek fine art and, of course, Russian avant-garde. Though the collection remains intact, the museum’s remote location in Uzbekistan’s far-off desert prohibits many would-be patrons from viewing the exhibits. Babanazarova managed exhibitions in Germany and France during the 1990’s but, excluding a 2011 display of three paintings in the Netherlands, the Uzbek Ministry of Culture refused all subsequent invitations to display the collection abroad.

The Uzbek government then displayed ambivalence towards Soviet Russia’s Cold War imperialism and, by extension, the Russian avant-garde that remains. Preferring instead to promote regional folk art, such as weaving and engraving, Savitsky’s remarkable collection of predominantly Russian artifacts challenged the Uzbek government’s narrative much in the same way that it challenged Stalinism’s censors. It’s other challenge came from the fact that the massive collection was valued at more than a billion dollars. Knowing that there were ready buyers, some officials wanted to see at least some paintings auctioned for the good of Uzbekistan… or perhaps just for themselves.

In November 2010, while Babanazarova was out of town on business, officials suddenly declared the original museum building condemned. Granted just forty-eight hours to evacuate its contents, employees haphazardly piled fragile canvases on the new building’s exposed basement floor. Despite the fall of communism, socialist realism, and the Soviet Union, the avant-garde collection remains vulnerable.

The Desert of Forbidden Art, an American-made documentary released earlier in 2010, provides a possible cause for the State’s abrupt behavior. By highlighting the various challenges facing the Nukus Collection, the directors hoped their film would renew efforts to exhibit works abroad. Babanazarova accepted invitations to premiers in Greenwich Village and Washington, DC, but at the last minute, Uzbek officials denied her transit. As an influential woman with a degree in English and who promotes dissident art, authorities were suspicious of her relationship with foreigners and growing international prominence. During the summer of 2015, her troubles, far from over, erupted in scandal: authorities accused Babanazarova of pilfering from the museum and fired her from her position. Her supporters claim that Uzbek authorities fabricated the story to offset their jealousy of the Savitsky collection’s international acclaim. Babanazarova’s dismissal sparked rumors that the government hoped to move the collection to the Uzbek capital of Tashkent. Cynics suspected that many of the artifacts would disappear—much as their architects did—during the move.

Thankfully, the move never happened.

The Museum and Collection Today

The museum went through several leadership changes after Babanazarova was ousted and fears for the collection remained. Then, in 2016, the country’s first post-Soviet change of power occurred. Islam Karimov, who had held power since before independence and held the country in a conservative mold of its former Soviet self, suddenly died. He was replaced by Shavkat Mirziyoyev who immediately set out to modernize the country and integrate it into regional and global political and economic structures.

In 2017, the Savitsky collection travelled outside the country again. In a gesture of goodwill engineered to strengthen cultural and state relations, Uzbek authorities worked with their Russian counterparts to schedule the “Treasures of Nukus” exhibit to coincide with a state visit between Uzbekistan’s newly inaugurated Mirziyoyev and Vladimir Putin. The event was hosted at the renowned Pushkin Museum and displayed about 200 of the collection’s most iconic items. While the exhibit was scheduled to run from 7 April to 5 May, its unprecedented popularity prompted administrators to grant the exhibition a three-week extension.

In 2019, Uzbekistan announced a world-wide competition for a new director of the Nukus Museum. Tigran Mkrtychev, who had formerly headed the Roerich Museum in Moscow and who was a former Deputy Director of the Nukus, won and was subsequently appointed director in 2021. Like Savitsky, he comes from a background in archeology and is a long-time enthusiast of Karakalpak culture. Most have welcomed his new leadership as a potential new era of stability for the collection. The museum has started public outreach and offers sponsorships much like many western museums – although the museum remains remote and most of its patrons will likely only ever visit once if at all.

Now considered the “Louvre of the Steppe,” the mythos of the Nukus Museum is well established and it remains a tourist attraction for die-hard art connoisseurs and Soviet history buffs. Former director Babanazarova once said of the Nukus that “[Savitsky] always said people would come from Paris to see it, and now the French are our number one [international] visitors.”

This article was originally written by Katherine Weaver in 2017. It was updated and expanded by Josh Wilson in 2024.

You’ll Also Love

The Evolution of Art and Painting in Central Asia

While Central Asia has a long, rich history, the modern nations of the region are a direct result of 20th century colonization. Prior to Soviet interference, the many ethnic groups and distinct societies of the region were loosely grouped under the geographic term of Turkestan. Under Soviet control, the region was divided into the Turkmen […]

Nukus Museum in Uzbekistan: Lysenko, Savitsky, and Preserving the Soviet Avant-Garde

In the remote Nukus Museum of Uzbekistan, a vast collection of banned Russian avant-garde art has been preserved for decades. The museum and its collection were founded by Igor Savitsky, a Soviet artist who defied censors to rescue and safeguard these works. His success was also made possible by the unique geography and history of […]

A Day in Tashkent’s Old City: Travel from Bishkek with SRAS

As part of SRAS’s Central Asian Studies program, students had the opportunity to travel to Uzbekistan for a full week. The first day of this week-long expedition began with a half-day tour of Tashkent’s old part of town. We were accompanied by our guide, Donat, or “Don” for short. He had outstanding English, and even […]

The Uzbekistan State Museum of Applied Art

The State Museum of Applied Arts of Uzbekistan provides an excellent introduction to Uzbek history and culture. Centrally located in Tashkent, it displays more than 7,000 examples of traditional folk art. These include a range of mediums from decorative glass to porcelain and fabrics, all dating from the first half of the 19th century to […]

Saira Keltaeva: Exploring Uzbek and Feminine Identity

Many describe Saira Keltaeva as one of the most unique phenomena emerging from the modern Uzbek art scene in recent decades. Born on May 16th, 1961, in the village of Kumyshkan, located in the Tashkent region of modern day Uzbekistan, her oil paintings master the use of vibrant color and ethnographic decoration to create portraits […]