As part of SRAS’s Central Asian Studies program, students had the opportunity to travel to Uzbekistan for a full week. The first day of this week-long expedition began with a half-day tour of Tashkent’s old part of town. We were accompanied by our guide, Donat, or “Don” for short. He had outstanding English, and even knew his fair share of slang and colloquial phrases in addition to higher level vocabulary. Therefore, a day with our guide made it very easy for us to comprehend a plethora of new information. By the end of this half-day excursion, we had already learned a lot about Uzbekistan, Tashkent, and its surrounding culture.

Our excursion included a trip to the city’s religious center, a trip to the bazaar, then a museum, and finally a traditional Uzbek dinner at a local restaurant. When we first got in our marshrutka (mini-bus), Donat gave us a very thorough rundown of both Tashkent and Uzbekistan, their history, their current economy, and overall state of affairs.

Uzbekistan has a total population of thirty-three million people, making it the most populated country in all of Central Asia. It has twelve different regions, represented on its flag with twelve stars. In terms of demographics, 85% of inhabitants are ethnically Uzbek, with the remaining populace from minority groups of Kyrgyz, Tajik, and ethnic Russians and Koreans. Donat explained to us how Stalin forcibly moved many Koreans from the Russian Far East to Central Asia during Soviet times, because he feared that they might be spies.

Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, has a total population of 3 million that incorporates all these ethnic groups. Thus, while Uzbekistan is a majority-Muslim country, in addition to mosques, other places of worship exist in Tashkent, such as Catholic and Orthodox churches and three synagogues.

Tashkent is located in the Oasis Region, which has been named so because of the 162-kilometer-long Chirchik River that flows through the city. Because of the river, and despite the area’s propensity to occasional earthquakes, Tashkent was selected as the new capital city for the Uzbek SSR 1930, and massive construction began to expand the city.

A great earthquake occurred in Tashkent in 1966, after which approximately 2/3 of the city had to be rebuilt. Despite the intensity of the earthquake, which was over eight points on the Richter scale, only eight people died.

In terms of Uzbekistan’s economy, most cars that are on the road have been locally manufactured in Uzbekistan’s Ferghana Valley, known as an area of crossroads between the cultures of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Tourism is also a booming industry in Uzbekistan with more westerners coming annually to admire the ornate mosques and madrassahs, many of which have been restored.

The name “Tashkent” means “city of stone,” and there are two schools of thought as to where this name came from. The first is that Tashkent was long a prosperous city with many important stone structures. The other alternative is that travelers were impressed with the bravery of the local people.

Uzbekistan was long important economically, being a crucial part of the Silk Road, and Chinese merchants often passed through Tashkent.

Uzbekistan thus shows some Chinese influence, but also strong influences from Persian, Arab, and Russian cultures. This unique combination of cultures is what has made Uzbekistan into the unique country that it is today. But in order to understand these influences, it is necessary to understand Uzbekistan’s history. In the eighth century, Tashkent was captured by Arabs, who tore down the old city and built a new city in its place. The Arab influence was evident in the architecture of the many mosques and madrassahs that we visited that day. Our guide explained to us that because of the respect for mortal life that Islam promotes, it is forbidden to depict humans or animals on buildings. For that reason, the designs that we saw were largely based on geometric patterns, and at times contained quotes from the Quran. All of these buildings had a similar color scheme of various shades of blues. Floral patterns were also a common sight since they are traditionally used to adorn Islamic religious buildings. Another common pattern were geometrical shapes similar to those found in Syria during the time of the Roman Empire. This was fitting since Uzbekistan was under the rule of Alexander the Great during the fourth century.

Amir Timur, also known as Tamerlane, is regarded as Uzbekistan’s greatest ruler. When in rule, he transferred power to the emirate of Bukhara and then back to Kokand, a previous name for Tashkent. It was during this time that Tashkent experienced a medieval renaissance. Around this time in the fifteenth century, the Uzbek poet Nizamuddin Mir Alisher Navoi became famous, and is now considered the father of the Uzbek language and a national hero. There is even a town in Uzbekistan named after him.

More recently in history, when the Russian empire took over in 1865, Russian cultural influences began taking shape in the region. In 1917, the Bolsheviks came to power, and shortly thereafter Uzbekistan became a part of the Soviet Union. On September 1, 1991, Uzbekistan declared its independence from the Soviet Union. As in most former Soviet countries, Russian remains a state language in Uzbekistan.

After learning all about Uzbekistan and its history along our tour through the city, we arrived at Tashkent’s religious heart in the city center. In this area, we walked down a corridor to see the way that people used to live here. Along these small corridors were two-story windowless homes made from a mix of clay and straw. Our guide said, rather jokingly, that the reason for such windowless homes was so that nobody could gaze upon your wife. In reality, this was the truth. Our guide explained to us the very conservative culture that Uzbeks previously followed, and that they, in some ways, still continue to follow. Women used to have to wear burkas in the street. Although burkas are no longer required, those who live in this religious center still tend to live very traditionally. Two or three generations will still live together in one house, many of which are most likely couples who had their marriage arranged by their parents.

The next thing we saw was the Khast Imam Square. In Arabic, “khast imam” means “holy preacher.” Inside of this mausoleum, a holy preacher is buried. He came from the family of a locksmith and is credited with spreading Islam to Tashkent. In his youth he studied at a madrassah, or religious school. Our guide, Donat, said that the khast imam could be compared to a Catholic Saint in terms of how much this man is honored by Muslims. All 114 surahs of the Quran adorn this mausoleum. Upon entering, we had to cross under an arch, which is symbolic of entering into paradise. In order to pay respect, you may bow upon crossing under this arch. Originally built in the tenth century, the mausoleum was restored in the fifteenth century.

Upon entering this mausoleum, the tombstone of the holy preacher was directly to our right. Our guide pointed out the dome shape of the building, which he explained had a dual purpose. One was that the dome was symbolic of reaching up to heavens. The other was architectural in that domes naturally insulate buildings and retain warmth during warm months and keep the inside air cool during hot months.

There was also a section of the inside of this mausoleum that was dedicated to the Ishan Preacher Basbasan (Бобохон). During the time of the Soviet Union, Muslim holy sites were deemed forbidden. Babasan took a stand for Islam during this time. Stalin and Basbasan had a meeting together during which Stalin gave him permission to establish the Central Asian Council of Muslims. This evident demonstration of Stalin loosening his grip on religion was a small victory. Following Stalin’s death in 1953, Uzbekistan was already enjoying more religious freedom as people were yet again granted access to holy places for worship purposes.

Our next destination was a nearby square that has a mosque, a madrassah, a museum and minarets. The Barakan Madrassah was built here in the 15th century. Slightly less intricate than the other buildings we had seen, it was a long, brown building. Barakan means “the lucky one.” The history behind this is that a man, whose wife was barren, prayed to God promising to build a madrassah if he had a child. So, when his wife became pregnant, he became a patron of education. The Tillya Sheikh Mosque is nearby, with a capacity for 400 people. On holidays, 800 or 900 usually come and many end up praying outside on the street. The mosque is very tall, reaching 43 meters (141 ft). Our attention was brought to the sandalwood designs adorning the entry way. In this same spot, there were also gereh (girih) geometrical patterns, which came from Syria at the time of the Roman Empire. Nearby there were two minaret towers on either side of the mosque, which we learned were once scaled by Muslim teachers to call all nearby Muslims to prayer. Nowadays, there are loudspeakers at the top of these buildings.

The main attraction here was the oldest Quran in the world, held by the small Barakan Muyi Mubarak Library in the center of the square. This was the Quran that belonged to the third Caliph, Uthman, in the mid seventh century. It was printed using natural ink from plants. At one point, clergymen in Saint Petersburg paid to have it sent to that Russian city for study. Babasan saw the book rightfully returned to Uzbekistan.

We now transferred to the local bazaar. On our way there, we saw a monument built honor Shamakhmudov, a blacksmith and WWII hero who adopted 15 kids from many nationalities. The monument was built in 1982, by Soviet architect Aitmatov. We also stopped at one more madrassah where secular and Islamic studies still occur alongside each other even to this day. Students get placed in different subdivisions: general Islam and the history of Muhammad the Prophet. While this madrassah used to have three levels, now it has only two. This madrassah administers an entrance exam each year and admits between 15 and 20 new students annually. Those who score high are given a scholarship. Upon graduating, students are qualified to work as clergymen or preachers. There are thirty such Islamic universities in all of Tashkent.

Finally, we came to Choor Soo Bazaar. Its name means “old tower” or “old arsenal” in Persian. Old Tashkent was made up of four districts and there were twelve city gates. The bazaar is the place where these four districts met. It is considered Uzbekistan’s most authentic bazaar, because of its long history.

One of the first bazaar merchants saw was selling sugar crystals, or what we would refer to in America as simply “rock candy.” Here it is called “navat,” and the darker it is, the more crystallized it is. Sticking with the traditional nature of the bazaar, only beef, lamb, or horse meat is sold, and never pork. Since the weather was a bit brisker than we were expecting, this gave some of us students an opportunity to buy hats and gloves if needed.

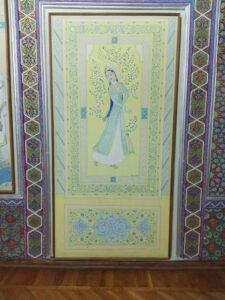

The final leg of our excursion for the day was a trip to the Museum of the Applied Arts. We started off by taking a look at, and learning more about, what was perhaps the most impressive exhibit – the suzani, a form of needle-work. These large tapestries were traditionally given as part of a dowry to a new husband. This was a tradition passed on from generation to generation. Sometimes, suzanis would be left unfinished by a mother to be completed by her daughter – a symbol of continuing the bloodline. Functionally, suzanis were used as bedclothes for newlyweds, and were symbolic of loss of virginity. Just as we had learned about during our time in Turkmenistan, women in Uzbekistan were also considered more valuable if they had superior domestic abilities. With suzanis in particular, these skilled were valued because they could produce items for sale that could then generate family revenue. The large suzanis we saw took somewhere between one and ten years to finish, depending on the nature of their intricacies. Suzanis are made from three separate pieces that are stitched together. Beginning in the twentieth century, with the arrival of the Russians, suzanis started becoming machine-made. While different objects on suzanis mean different things, by far the most popular were flowers because Muslims believe that when you ascend to heaven, you’ll see flowers.

In our next section, we saw the garb that was formally worn by women. They used to have to wear horse hair covering their face whenever they went out in public, in addition to a huge jacket, of which the length of its sleeves signified whether she was married or not. This was because, according to Sharia law, a woman would get stoned if she left the house clothed improperly. These sorts of struggles gave way to eventual movements surrounding the liberation of women.

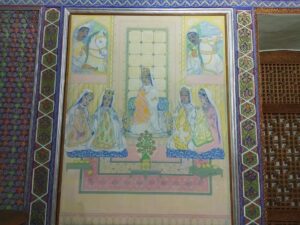

Following this section, we learned more about what is involved in a marriage ceremony, which is regarded at the most important and holiest event in one’s lifetime. Weddings are still traditionally large with somewhere between 400 and 500 attendees. Arranged marriages are still largely a part of the culture, because people feel a sense of obligation to listen to their parents’ wishes. In this section, we took a look at some instruments that are traditionally played at weddings, such as the naga, a stringed instrument. There were also various Chinese instruments, thus denoting the Chinese influence in the region. Another instrument was the dutar, which was a two-stringed popular Uzbek instrument made from poplar trees, which are light and abundant.

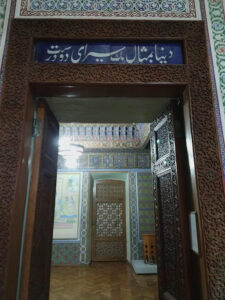

Next, we were brought to a temple-like area. We looked at some Zoroastrian paintings, which was the predominant belief system before Islam in this region. One of the paintings depicted Mother Spring, or Narus, celebrating the beginning of the New Year on March 21st. On our way out of this area, our attention was directed to a sign written in Arabic, which says that “Life is like a guest house. Every day someone goes in and someone goes out.” This is a metaphor for life, birth, and death and was to serve as reminder to be prepared for the afterlife.

The last area of the museum had many ancient household items. For example, we saw some traditional plates with cotton ball designs – a national symbol of Uzbekistan’s culture and economy. We also saw teapots, and an interesting sort of invention that turned out to be a sink. It was a basin with a hole in the middle, designed so that when guests wash their hands, nobody can see how dirty they were. This was meant as a polite gesture.

There were other statues in this section. One was of a peacock, which we learned was the bird of happiness, and is on Uzbekistan’s coat of arms. In this area, there was also a display of women’s jewelry. A bride would wear as much as eight kilograms (seventeen pounds) of jewelry made from heavy materials, such as brass and bronze. She would continue to wear this after she got married for a duration of forty days. This jewelry would be brought into her husband’s house, but it always stayed with her, even if the couple divorced. During these times, a husband could simply say “I divorce you” three times, and the marriage would be dissolved.

Finally, to end our excursion, we had a traditional Uzbek dinner at a local restaurant. We were all expecting plov as our first meal since it is a national Uzbekistan dish, and perhaps the most popular. Instead we started off with a tomato, red onion, and basil salad. The basil was a nice break from dill, which is on almost every single dish you can think of in Kyrgyzstan. Then we had a lentil soup, and for our main course, a meat and tomato dish. The dessert was a hot apple with ice cream. It was a delicious meal and a great way to end our first day in Uzbekistan.