“If a student came to you and said that they were interested in Russian or Soviet art but were unsure where to start exploring it further, what books and authors would you recommend?”

This question was asked by SRAS Intern Taryn Jones of Elena Varshavskaya, who for many years taught art history at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and Eastern Connecticut State University, and who directed the art programs run by SRAS.

Although the question was asked more than decade ago, the list given stands as a timeless foundation to the subject. While some of these works are now out of print, students should be able to find them through interlibrary loan. We’ve also provided links to Amazon’s offerings, when available and otherwise to links that provide more information when not.

Recommended Books on Russian and Soviet Art

The great majority of the recommended books below are out of print. The Amazon links provided are nearly all to used books for sell. Some of these are quite cheap and some are very expensive. However, all these books should be available on interlibrary loan, available from your university library or any local public library.

General works

- A Concise History of Russian Art, Rice, Tamara Talbot

- The George Riabov Collection of Russian Art, Zimmerli Art Museum

- A History of Russian Architecture, Brumfield, W.

- History of Russian Painting, Bird, A.

- The Icon and the Axe: An Interpretive History of Russian Culture, Billington, James

- An Introduction to Russian Art and Architecture, Auty, R. and D. Obolensky, eds.

- Treasures and Traditions, Allenov, M., et al,

- The Wooden Architecture of Russia, Opolovnikov, A. and Y. Opolovnikova

Early Russia

- Early Russian Architecture, Faensen, H. and V. Ivanov

- Gates of Mystery. The Art of Holy Russia, (exh. cat.)

- Icons, Onasch, K.

- The Glory of Byzantium, (exh. cat.)

- Old Russian Murals and Mosaics, Lazarev, V.

17th – Early 19th Centuries

- The Art of Russia 1800-1850, (ex. cat.)

- The Empress and the Architect: British architecture and gardens at the court of Catherine the Great, Shvidkovskii, D.O.

- The Russian School of Painting, Benois, A.

- The Russian Canvas, Blakesley, R.

- Life on the Russian Country Estate, Roosevelt, P.

- Russian Art from Neoclassicism to the Avant-garde, Sarabianov, D.

- Russian Folk Art, Hilton, A.

- St. Petersburg: architecture of the tsars, Shvidkovskii, D.O., Orloff Alexander

Second Half of 19th Century – Early 20th Century

- Russian Painters of the Early Twentieth Century, Sarabianov, D.

- Russian Realist Art, the State and Society: the Peredvizhniki and their Tradition, Valkenier, E.

- Russian Realisms, Brunson, M.

- The Wanderers: Masters of 19th century Russian Painting. (ex. cat.)

- Ilya Repin, Sarabianov, D.,

- Alexei Venetsianov, Sarabianov, D.

- Valentin Serov, (Great Painters), Sarabianov, D.

- The Mir Iskusstva Group and Russian Art, Kennedy, J.

Twentieth Century Avant-garde and Revolutionary Period

- The Bolshevik Poster, White, S.

- Constructive Strands in Russian Art 1914-1937, Lodder, C.

- Essays on Art, Malevich, K.

- Neizvestnyi russkii avangard, Sarabianov, A.

- Paris-Moscou, (exh. cat.)

- Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism 1902-1934, Bowlt, J.

- Russian Avant-Garde Books, 1917-34, Compton, S.

- The Russian Experiment in Art, 1863-1922, Gray, C.

- Russian Futurism, Markov, V.

- Street Art of the Revolution, Tolstoy, V, I. Bibikova, C. Cooke,

- Women Artists of Russia’s New Age, Yablonskaia, M.

Soviet Avant-garde; Socialist Realism, Non-conformist Art

- The Great Utopia (Velikaia Utopia), (exh. cat.)

- “The Great Russian Utopia,” Armas, V., D. Elliot, C. Lodder,

- Pioneers of Soviet Architecture : the search for new solutions in the 1920s and 1930s, Khan-Magomedov, S.O; Cooke, Catherine

- The Soviet Photograph, Tupitsyn, M

- Khrushchev and the Arts–The Politics of Soviet Culture, Johnson, P. and L. Labedz

- New Art from the Soviet Union: The Known and the Unknown, Dodge, N. and A. Hilton, eds.

- Soviet Art in Exile, Golomstock, I. and A. Glezer

- Contemporary Russian Art, Bown, M. C.

- 100 Years of Russian Art from Private Collections in the USSR, Elliott, D. and V. Dudakov

- Between Spring and Summer: Soviet Conceptual Art in the Era of Late Communism, Ross, D. et al.

- The Quest for Self-Expression: Painting in Moscow and Leningrad 1965- 1990, Kornetchuk, E.

- From Gulag to Glasnost: Non-Conformist Art from the Soviet Union, Dodge, N. and A. Rosenfeld, eds.

Authors

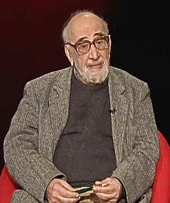

Selim Khan-Magomedov

Khan-Magomedov has been widely recognized for his outstanding contribution to two very distinct fields of study, namely Dagestani architecture, and the Russian avant-garde movement during the 1920s and 1930s. A leading contributor to research on the avant-garde, he has written countless monographs, articles and books, including the legendary Pioneers of Soviet Architecture, Pioneers of Soviet Design and One Hundred Masterpieces of the Soviet Architectural Avant-Garde. He has written on the most important architects of the Russian avant-garde, including Konstantin Melnikov, Alexander Vesnin, Nikolai Ladovsky, Alexander Rodchenko, Moise Ginsburg, Ivan Leonidov, and Ilya Golosov. Khan-Magomedov contributed greatly to the scholarly research about Russian avant-gardists, and in the course of studying the personal archives of over 150 Russian architects, artists, designers and sculptors, revealed a number of previously unknown facts about their lives.

In his work on the architecture of Dagestan, Khan-Magomedov has personally identified and studied more than 1000 architectural monuments in Dagestan, and has written widely on the subject.[2] His works include Folk Architecture in Southern Dagestan, Lezgin Folk Architecture, and Dagestan Mazes.

Khan-Magomedov holds a doctorate in art history and is an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Art. In 1992, he was awarded the Russian Federation’s “Distinguished Architect” title, and in 2003, he was awarded the State Prize of Russia for his contributions to the field of architecture.

Selim Khan-Magomedov was born in Moscow on 9 January 1928, and passed away on 3 May 2011 at the age of 83. He was the son of well-known war engineer Omar Khan-Magomedov, and the brother of literary critic Marietta Chudakovaya.

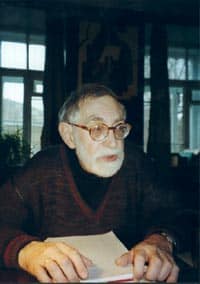

Igor Golomshtok

Golomshtok (sometimes written “Golomstock”) was born in Kalinin (modern-day Tver), Russia on 11 January 1929. In 1934 his father, Naum Yakovlevich Kodzhak, was arrested on the charges of “anti-Soviet propaganda” and sentenced to five years in a prison camp. As such, Golomshtok was registered in school under his mother’s maiden name, which he continues to retain to this day. In 1937, mother and son moved to Moscow, where they resided for two years before relocating to Magadan, where they lived until 1943. Surely influenced by these early experiences, Golomshtok gravitated towards anti-communist art criticism.

Golomshtok’s roots were not originally in art history; he graduated from Moscow’s Financial Institute in 1949. However, he had clearly been drawn to art history early on, and began taking night classes at Moscow State University’s art history department in 1948, while still studying at the Financial Institute. Between 1955 and 1963, Golomshtok was employed in the department of traveling exhibitions at Moscow’s Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, where he worked in the research workshop for the restoration of architectural monuments.

In 1965, Golomshtok was called before the courts to testify in the pivotal Sinyavsky-Daniel case against Russian authors Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel. The trial is widely acknowledged to be “symbolic of the end of the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’ and the beginning of the Brezhnev era.” However, having co-authored the Soviet Union’s first work on Picasso with Sinyavsky, Golomshtok refused to testify, and as a result, was sentenced to six months’ hard labor. In 1972, Golomshtok moved to Britain. He died there on 12 July 2017, aged 88.

The move to Britain did not stop Golomshtok’s involvement with the Russian arts scene. He contributed to the inaugural edition of Kontinent, which was founded in 1974 with writer Vladimir Maksimov as editor-in-chief. From the beginning, the journal included the works of Western writers and intellectuals, as well as those of Russians living abroad. The four guiding principles of the journal were those of unconditional religious idealism, unconditional antitotalitariansm, unconditional democratism, and unconditional antifactionalism. Golomshtok was also published in the journal Syntaxis.

Golomshtok’s contributions to the literature and arts scenes have not been limited to Russian works. During the Soviet era, he translated Arthur Koestler’s novel, “Darkness at Noon,” which was circulated as samizdat (a self-published work), and has, more recently, published works on Picasso and the art of Ancient Mexico. He has written countless pieces on Russian art, including Totalitarian Art in the Soviet Union, the Third Reich, Fascist Italy and the People’s Republic of China. His work has influenced scores of researchers, including those “scholars responsible for a profound recasting of the Stalin period.”

Golomshtok taught at the Universities of St Andrew’s, Essex, and Oxford, and worked with the BBC’s Russian service for many years.

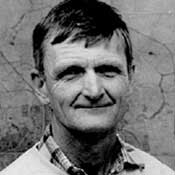

Dmitry Sarabyanov

Sarabyanov was born in Moscow on 10 October 1923, the son of Vladimir Sarabyanov, a Marxist philosopher. He later married Elena Murina, a Russian art critic.

Sarabyanov’s early life was marked by the arts, athletics, and travel. In the 1930s, he was actively involved with athletics, and in 1936-1937, he was the USSR’s primary school high jump champion. In the same year, he traveled with his father and brother to the Caucasus, and along the Siberian rivers of Yuryuzan, Ufa, and Belaya. During his childhood, he also tried his hand at composing music, and began writing poetry, a hobby which he continues to pursue.

After graduating from high school in 1941, he attended Moscow State University, enrolling in the department of art history. It was at this time that he also began work as an art critic. Unfortunately, his studies were briefly interrupted by the Second World War and his service in the Soviet army, for which he was awarded both the Order of the Patriotic War and the Military Merit medal. Following demobilization from the army, he returned to Moscow State University to continue his studies, and upon graduation, applied for and was accepted to a graduate program in art history. He graduated in 1952, and by 1955, he had been admitted to the Union of Artists. In the same year, he began work as the senior researcher at the USSR’s Academy of Sciences, and went on to hold the positions of Deputy Director and Head of the Institute of Art History before his departure in 1960.

Between the years of 1966 and 1996, Sarabyanov held multiple positions at Moscow State University, including those of associate professor, head of the art history department, and Russian art history consultant. He earned his PhD in 1971, and his research interests include the history of Russian art, non-Russian art during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, issues in the relationships of art and literature, the interaction of Russian and Western art and peculiarities particular to the Russian avant-garde movement. He has published over 360 articles and books, and in 1992, he was elected to the Russian Academy of Sciences. He died in Moscow in 2013.

Christina Lodder

Dr. Lodder is one of the West’s leading avant-garde specialists, and focuses her research primarily on the art of the 1910s and 1920s. She has written a major study of Russian Constructivism, which has been acclaimed as the standard work on the subject. She co-authored a major monograph on the works of Russian sculptor Naum Gabo with her husband, Martin Hammer, and has also edited a collection of Gabo’s writings. In 1985, working in tandem with Colin Sanderson, she published the Catalogue Raisonné of Gabo’s work. Her works cover everything from the development of new teaching programs during the early Soviet era and the implementation of Constructivist ideas in the areas of photography, textiles, and Theater, to a discussion on Vladimir Tatlin’s The Model for a Monument to the Third International of 1920. She also spends her time researching the influence of the Russian avant-garde on the art of Central and Eastern Europe, and has more recently spent time writing on the relationship between art and science first discussed by Kazimir Malevich.

Dr. Lodder is currently an honorary professor of history of art at the University of Kent. She is a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as well as the Royal Society for the Arts, and is the president of the Malevich Society of New York.

John Ellis Bowlt

John Ellis Bowlt was born in London, England on 6 December 1943, and currently teaches at the University of Southern California. He completed his PhD in Russian Literature and Art at Scotland’s St Andrew’s University in 1971, and his main research interests include Russian literature and art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as well as twentieth century Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia. He has written countless books and monographs about the Russian avant-garde, Russian stage design in the years 1900-1930, the memoirs of Benedikt Livshits, and Sergei Diaghilev. He has also written on the Russian Silver age, Léon Bakst, and a catalogue raisonné on the stage designs of Nina and Nikita D Lobanov-Rostovsky.

Bowlt has been awarded numerous awards and grants, including most recently a Fullbright-Hays follow-on award to continue research on the works of Léon Bakst in Moscow and Europe in 2010, and the Order of Friendship, which was awarded by former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev in 2009. In 2012, he was awarded $17,000 from Moscow’s Prokhorov Foundation towards the publication of the English translation of the literary legacy of Léon Bakst. For this work, he also received $10,000 from the Advancement of Scholarship in the Humanities and Social Sciences from the University of Southern California. Bowlt has taught and lectured internationally, including work as a visiting professor at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University in 1985 and New Zealand’s University of Otago in 1982. He was a Slade Visting Professor at the University of Cambridge from 2015-16.

John E. Bowlt currently teaches Slavic languages and directs the University of Southern California’s Institute of Modern Russian Culture.

You’ll Also Love

The State Museum of Political History of Russia

Centrally located in St. Petersburg, the State Museum of Political History of Russia examines Russia’s tumultuous political history. It does so in a way that is both modern and quite balanced. Exhibits in the main building are shown in an attractive, recently-renovated tsarist-era mansion with modern technology and artful multimedia presentations. Exhibits give a wide […]

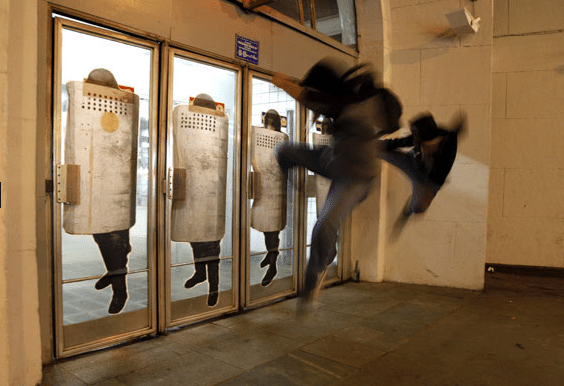

Russian Protest Art that Isn’t Pussy Riot

When most think of Russian protest art today, they think immediately of Pussy Riot, the long-famous, all-female punk movement. These women have, since their “punk prayer” launched them to international notoriety, been heavily covered in the English-language press and heavily studied in English-language academia. However, Russian protest art is a diverse genre with a long […]

The Nabokov House Museum in St. Petersburg

The Nabokov House Museum stands only minutes away from Russia’s famous Saint Isaac’s Cathedral on Bol’shaya Morskaya utlitsa in St Petersburg. The only signs advertising the museum are two small stone cravings that identify the building as Nabokov’s former home. Otherwise, the museum is a hidden literary treasure, available to those that know where to […]

The Viktor Tsoi Graffiti Wall in Moscow

Coming across the graffiti wall at the corner of Stary Arbat and Krivoarbatskaya Lane last summer, I took a few pictures, and didn’t think about it much more than that, except that I was surprised to see such elaborate work in such a public place. So when I visited the same place, and saw that […]

Irkutsk Drama Theater

In early December we finally got a chance to go to the Irkutsk Drama Theater for a performance of Gogol’s comedic play, Marriage (Женитьба). It was enjoyable and funny, even if we didn’t understand about sixty percent of the dialogue. The actors were very good and made us laugh throughout the play, through both their […]