Faith Seim, after studying at for an academic year (1999-2000) at Moscow State University with SRAS, applied to and was accepted to study film direction at the All-Russian State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK). She eventually went on to work in the studios of RAMKO/Russian-American Movie Company, a Moscow-based film company specializing in producing films “for the international market” and in English.

SRAS: Can you tell us how you first became interested in Russian and why you decided to study abroad in Russia?

Faith Seim: Initially, I studied Russian because I was in a relationship with a Muscovite whom I had met while working at a US national park one summer. I wanted to learn more about his language and culture and, while an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota, enrolled in a Russian course that met one night a week. Then, thanks to SRAS, I was later able to study Russian for an intensive nine months at Lomonosov Moscow State University.

SRAS: You used that nine months to independently enroll in course at VGIK, Russia’s primer educational institute for film. What was the application procedure like for VGIK? What was the course work like and how did it compare to the sort of course work you might receive at a similar American institution?

FS: The application process was admittedly simpler for foreign students than for Russian applicants, for whom it was, I felt, much more intensive and competitive. I wrote three essays in Russian on topics provided by the institute, completed an interview with the faculty, and took a language assessment test. In comparison, I believe Russian students had a much more vigorous admission process and I felt that it created some resentment, initially, which was eventually overcome. Soon after my studies began, I made a request to switch from the foreign student group to the Russian group and the faculty member leading the group, the “Master,” recalled one of my essays and welcomed me to join him. In time, I came to feel completely accepted by my classmates and one of them even said, “ты – наша,” (you are one of ours), which really stunned me and for which I was very grateful.

I studied for two of the five-year program, as I had been told before my arrival that there was a two-year graduate program at VGIK. When I appeared at the school, I discovered this program actually didn’t exist (!), but decided to stay on and make the best of it because I felt a Russian arts education would be enriching.

The coursework is much different, I think… And I feel the Russian educational system is much different, in general. It seems to me that Russian education builds a very solid foundation. For example, at VGIK, we watched classical movies weekly in the great hall, starting from the Lumiere brothers and progressing through every era of filmmaking, from Eisenstein and Bergman and Fellini to contemporary films. My Russian boyfriend studied literature at MGU in much the same way, starting with 17th century literature and moving through each century in solid blocks.

I feel that the Russian approach builds brick-by-brick, whereas the American system, specializes a lot and sometimes leaves gaps.

On the other hand, I also found that Russian faculty seemed to have more absolute authority than I have felt in most American classrooms, which was something that required a shift in thinking. I like the space for respectful debate and questioning in an American classroom.

SRAS: So, having seen so many great Russian films, what are the top five that you would recommend students watch?

FS: Just the top five! That’s a difficult question. My favorite Russian movies include The Mirror, Cranes are Flying, Come and See (technically Belorussian), and the animated films Hedgehog in the Fog, Tale of Tales and the Oscar-winning animated film, The Old Man and the Sea. Ok, so that’s really six. But Hedgehog and Tale are a tie and by the same animator.

SRAS: What can you tell us about RAMKO/Russian-American Movie Company and how you found out about and landed a job there?

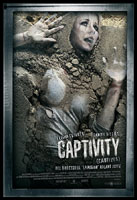

FS: By the time I landed the film job, I had been living in Russia for approximately five years (off and on). I was part of a Moscow-based listserv for “expats” (foreigners living abroad) and stumbled across the audition announcement for bit-parts in a Russian-American feature production, a thriller called, Captivity. It was serendipitous, actually, because I had stopped reading most of the emails from that listserve but decided to open that one, for some reason.

Initially, I auditioned as an actress for a small role, but I mentioned that I would be interested in crew work, as well. I was very interested in the project because it had a distinguished director, two-time Oscar nominee and Cannes/Golden Palm-winner, Roland Joffe (The Killing Fields, The Mission), as well as an Oscar-winning producer, Mark Damon (Monster, Das Boot), attached to it.

As luck would have it, the company was searching for bilingual employees at the time, as they felt it was more time/cost-effective than hiring interpreters. For that reason, I was hired as a production assistant and interpreter/translator for the art department. Soon, I was promoted to 2nd 2nd Assistant Director/Interpreter and also landed a small speaking-role in the film, although that role was later cut out in editing. This type of fast promotion doesn’t seem to happen very often in the US, but Russia seems to provide these gateway opportunities much more easily.

To be honest, I know very little about RAMKO’s ownership and funding. It seems the main producers are very successful Russian businessman in other spheres, as are the other co-producers. The company is a joint-venture between Russians and Americans but I believe it was mostly initiated from the Russian side.

SRAS: What was it like working on a bilingual film set? Do you think having an international cast and crew helped or hindered the creative process overall?

FS: The project itself was harrowing, in part due to the international aspect, but it was a wonderful learning experience. Admittedly, the Russian and American film crew worked together with difficulty, so I oftentimes felt somewhat obligated to play a diplomatic role. There was a lot of space for contact and growth between the two cultures – the opportunity was there -but I didn’t feel it take off and flourish. A lot of the old prejudices interfered with the process, I felt… Maybe because a lot of the crew were from the Cold War era and had a specific mindset. I felt the younger generation was freer of the old associations and more open towards growth and change, which is only natural, I guess.

From my understanding, part of the purpose of the Russian-American venture was for the Russian film industry to gain training and knowledge by learning about the American system of working with film, which is by necessity faster-paced and more efficient and cost-effective. I wonder if that didn’t have a lot to do with the difficulties on the set because it perhaps automatically places one group of people in a one-up position with implied superiority, if that makes sense?

I don’t feel that having an international cast or crew should necessarily hinder the creative process, although it presents a challenge. The creative process IS hindered, however, when an international cast and crew focus too much on their differences, rather than their similarities and shared humanity.

The film that we made was not exactly what was actually released in theaters, which was disappointing, but the experience, overall, was an opportunity to absorb a lot of interesting information and to forge a professional network.

SRAS: Out of curiosity, how and why was the film changed? Also, while I realize it’s tough to properly critique your own work (being from a Theater background myself), do you think either version lived up to the Oscar/Palme expectations you had for it?

FS: I wasn’t involved in any aspect of the project from the time the Moscow shoot wrapped in August 2005 until the time it opened in theaters in 2007, so the end result took me by surprise.

I never saw the initial version we made, which was created to be a thriller. To gain perceived audience approval, a lot of re-shoots were done after the Moscow shoot wrapped. It became less a psychological thriller and more of a horror film and had little resemblance to the script I remembered working on, so I would have to say that I did not see what I had expected to see in the movie theater, at all.

SRAS: And what are your plans for the future?

FS: Thanks to the gateway that this project provided, it looks like I may soon be joining another project in Argentina with the same director!

SRAS: We’ve read that the financial crisis is affecting the Russian film industry as well and film projects have been frozen. Have you heard much about this? Will it affect RAMKO?

FS: Yes, I’ve been told this is the case and the film industry, at large, is being affected by the financial crisis. Mosfilm is a quiet place, these days, and I have heard it has impacted RAMKO, too, whose offices are located at Mosfilm.

SRAS: As a final question, we get requests for assistance from students hoping to study performing arts in Russia. While we don’t currently have programs in this field, what advice would you offer to them?

FS: Russia seems a natural place for studying performing arts – It is a very dramatic place to live and, of course, rich in culture and history. I loved my Russian instructors and many aspects of the Russian educational system appealed to me. In Moscow and St. Petersburg, you are surrounded by a very accessible arts scene, so it’s a wonderful experience.

I suppose my only advice is to be willing and open to whatever comes, because, in my experience, nothing was really ever what it was presented to be or went the way it was “supposed to” and life in Russia is very unpredictable from moment to moment. Depending on your perspective, it can cause a lot of irritation, exasperation and fear or a sense of excitement and opportunity, if you remain open to growth and learning.

On the more practical side, I know that VGIK, MXAT, and GITIS all had non-Russian students while I was studying in Moscow… And I’m always happy to answer any questions, if I can.

Final note: VGIK, MXAT, and GITIS all currently accept foreign students who apply independently (currently SRAS is not authorized to assist in the enrollment process). This means that students must also interview in Moscow in Russian and in person. MXAT additionally has study abroad programs that run in conjunction with Wayne State University, for example.