Kazimir Severinovich Malevich is best associated with his stark, high-contrast works of oil on canvas like 1913’s “Red Square” and 1915’s “Black Square.” Like many of his works, these paintings feature a boldly-colored, opaque geometric figure atop a white background. Labeling his works under the umbrella of Suprematism, an abstract art movement sprung from the avant-garde, Malevich established his career on creating minimalist pieces highlighting “pure form.”

Malevich was born on February 23, 1879 to a Polish family in Kiev. The son of a sugar mill worker, Malevich’s family worked on beet farms, providing the future father of Suprematism with some of the subjects he’d depict in many of his works — particularly early in his career. Though his father had hoped his son would follow in his footsteps with a more traditional and practical trade, Malevich was absorbed by the arts from a young age. Taking up so-called women’s work in knitting and embroidery, he was taken by the stark contrast of the red and black stitching patterns made up of geometric shapes, typical of traditional Ukrainian cross stitch. While his interest in Ukrainian folk art was to the chagrin of his father, his mother bought him his first set of paints and helped to nurture his curiosity in the arts.

Malevich was sent by his father to Parkhomivka, a village in Ukraine, where it was hoped he would hone an agrarian trade. The experience helped Malevich decide that the agrarian peasant life he had grown up with was not the one he’d pursue. In 1904 he relocated to Moscow to apply to the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. The artist who would later become world-renowned for his misleadingly simple abstract pieces was rejected from the institution initially; he was accepted after subsequent applications after studying with painter and private art tutor Fedor Rerberg.

Under Rerberg’s guidance, Malevich became acquainted with movements and ideas that would come to greatly inform his philosophy and work. From Rerberg, Malevich learned many of the formal aspects of painting he had previously done without. Here he learned about painting anatomy and about perspective, as well as received an introduction to the Symbolists and Impressionists. Malevich had previously received no formal education.

As he grew as an artist under his mentor, Rerberg encouraged Malevich to start exhibiting his work and network with like-minded painters. At this time he was introduced to the influential Russian abstractionist Wassily Kandinsky, who himself — though born in Moscow — was raised in Ukraine. Kandinsky, like Malevich, was interested in the emotion and pure feeling art could evoke, as opposed to objective recreation or representation.

In the early 1900s he was occupied with painting rural scenes of peasant life. During this time period, he exhibited works like 1912’s “Peasant Woman with Buckets and Child,” which was composed with a primitive, simple take on anatomy. 1911’s “Taking in the Rye” presents peasant workers nearly as human cylinders, painted with only hints to normal body structure. Realism of anatomy devolved with his further development. “Head of a Peasant Girl” (1913) merely shows abstract triangles and circles to represent the peasant. This stage in his work recalls works by avant-garde painter Natalia Goncharova, who, around the same time, was creating works depicting peasant life and folk traditions.

Like many of his contemporaries, Malevich was influenced by the Cubists and had begun to create compositions reminiscent of works by others in the movement. In the early 1900s, some Russian artists deemed themselves “cubo-futurists,” putting themselves under the umbrella of both the fashionable Cubist and Futurist movements.. A spin on cubism pioneered by Pablo Picasso, and taking inspiration from Italian futurists, cubo-futurists were occupied with creating dynamic works depicting movement and action with objects and scenes fragmented into boldy colored and shadowed shapes. The focus on movement was influenced by a fascination with the speed of urban life and evolving technology. Examples of Malevich’s cubo-futurist works are 1913’s “Cow and Violin”and his many self-portraits

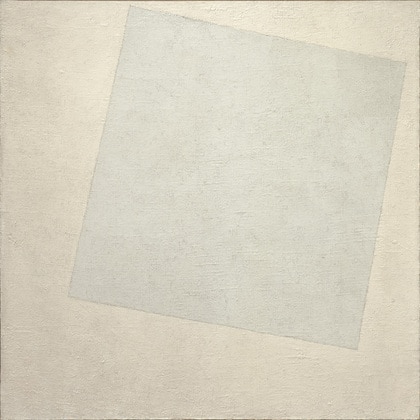

But soon, Malevich would synthesize his influences — impressionism, cubism and futurism — and marry them with his own artistic philosophy to establish Suprematism. Embracing geometric forms like the square and the circle and utilizing opaque colors of stark contrast, Malevich became controversial for his paintings like “White on White” and “Black Square.” Seemingly studies in form, line and shape, they differed greatly from his early narrative works and were a departure from classic studies of anatomy or landscape. Malevich maintained, however, that the objects of his work were indeed inspired by peasant life, just with forms reduced so greatly as to be represented only by a solitary color or geometric shape. To him, the simplicity of the form reflected the piety of peasants.

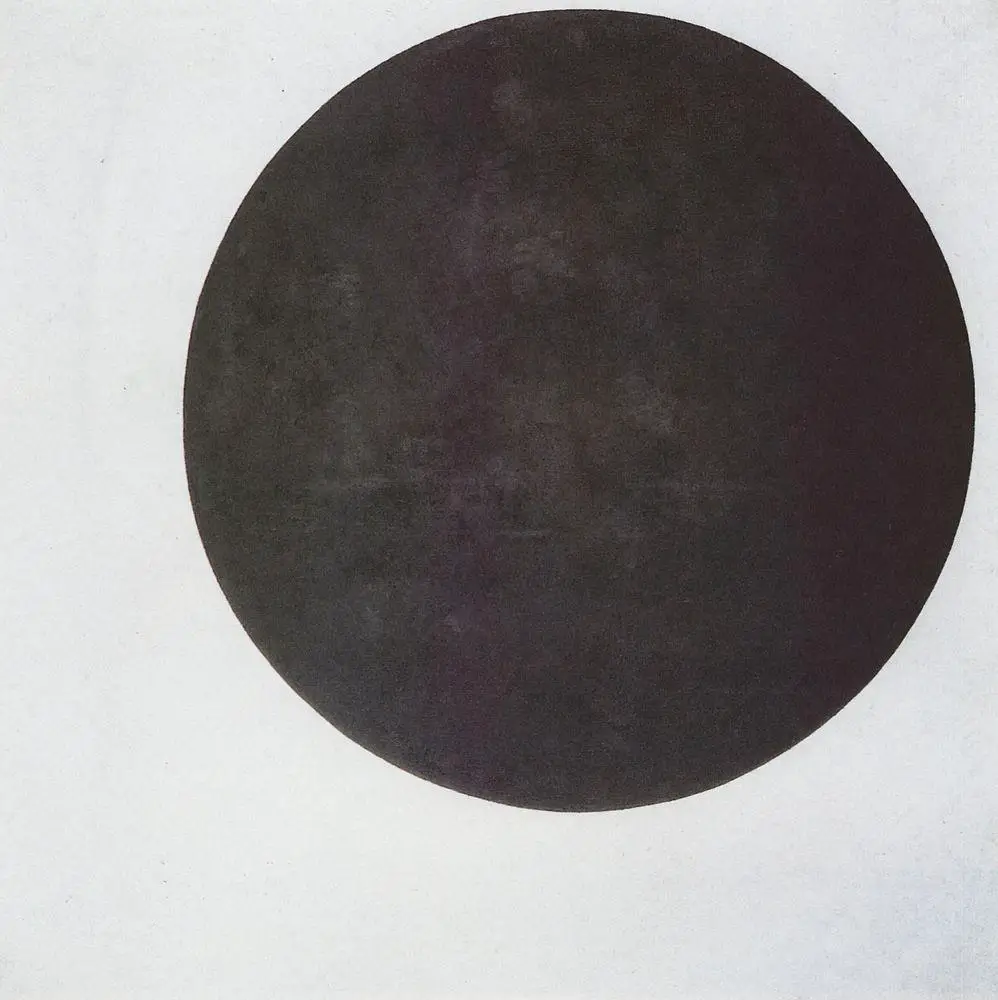

In December 1915 he exhibited “Black Circle” in St. Petersburg. Like many of his works to come, the oil on canvas painting consisted of an opaque black circle placed non-centered on a white square. Taking a cue from the Futurists, his release of this work coincided with the publication of his manifesto, “From Cubism to Supremism.” Here, he laid the foundations for his artistic philosophy, touting “the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.”

The term he coined for his aesthetic philosophy alone (“Suprematism”) communicates his belief that these new developments in art were overtaking the art of the past. His works were studies in “purity” of form — the stark contrast of black or red shapes upon a square white background, recalling again the color schemes of geometric Ukrainian cross stitch patterns. Declaring his works anti-utilitarian, he aimed to free his art from carrying social or political meaning, allowing him to glorify form for its own sake.

Many of Malevich’s seminal works were exhibited in 1915 through 1918, a time of pre- and early revolution. Soon after he had made his mark, the Soviet government adopted an unfavorable attitude toward most abstract art. Seeing little opportunity for art to be utilized for propaganda purposes, the regime began to support the spread of socialist realism. While his works were tolerated for a period of time, they were confiscated once Stalin came to power in the mid 1920s. He and many of his contemporaries were banned from further exhibitions. Still, he remained in the Soviet Union and taught art at various art schools in Russia and parts of what is now Ukraine and Belarus. He died of cancer in Leningrad on May 15, 1935.

Regardless of the official treatment by the Soviet government, Malevich has endured as one of the most influential abstract painters of the 20th century. In 2008, his “Suprematist Composition” (1916) sold in New York City for more than $60 million — setting a world record for any Russian work of art.

REFERENCES

Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism: 1878 – 1935, Gilles Neret

MoMA: The Collection

MoMA: Suprematism

Getty Museum: “Tango with Cows”

Northwestern University Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures 1, 2

Art Margins

Zorya Fine Art

www.day.kiev.ua