Two visitors had two very different experiences at the same museum – visiting just days apart. The Museum of the History of Georgian Medicine examines Georgia’s long history through the context of medicinal practices. Along the way, we learn quite a lot of Georgia’s identity and even genetic makeup. This particular museum is a reminder that all museums have narratives to tell about their subjects and that different audiences can have very different reactions to the same narrative. Museum science is as much art as science and its end product should spark thought and reflection.

A Worldview-Altering Look at Georgian History

By Dr. Yvonne Howell, Richmond University

The Museum of the History of Georgian Medicine in Tbilisi is not high on the list of most tourist itineraries. In fact, midday on a bright Sunday morning in early June, I was the only person there. The museum is not hard to get to – it is near the Marjanishvili Station on Tbilisi’s metro, and just off a busy, touristy street. Yet the minute you step into the garden surrounding the small museum building, it seems quiet and remote – like the ghosts of monks are growing their medicinal herbs in that garden.

A sign posted to the door says adult ticket without a tour costs 10 GEL; with a guide, it’s 25 GEL (about $9). I believe I would have had to pay 25 GEL to not get the tour. The sole person taking tickets turned out to also be a guide, and he could not resist the opportunity to give this lone visitor – who somehow radiated a vibe of I am interested in this stuff – his full attention. For the next two hours, he leads me through every object in the first-floor exhibit. (There is a second floor, but I ran out of time before I got to that).

My guide has an impressive grasp of the relevant English-language vocabulary (“they practiced trepanation for sub-cranial hematoma, a result, you see, when these knights are fighting with the swords”). He is of the generation that never had a chance to study abroad due to the social instability that came with Georgia’s independence; he pronounces every word exactly as it is written, with the full “w” in sword and the “k” in knight.

The exhibit tells a story of nation, medicine, and religion as three continuous, fully intertwined strands of history, going back to the 13th century BCE. The history of the Georgian nation is presented as inseparable from the history of medicine, and the development of medicine as inseparable from Georgian Orthodox Christianity. This is no ordinary story, in other words.

This is not the story of the immaculate conception of modern medicine somewhere in early modern Europe, from which it eventually grows into today’s international language of scientific terminology and practice, belonging equally to Indian, American, Cuban, Finnish, and Qatari doctors alike. No, no. In this museum, the history of modern medicine is traced directly back to the Kingdom of Colchis (today’s Georgia) in the first century BC, and from there even further back to pre-historic encounters of the early Greeks with the people of the Caucasus.

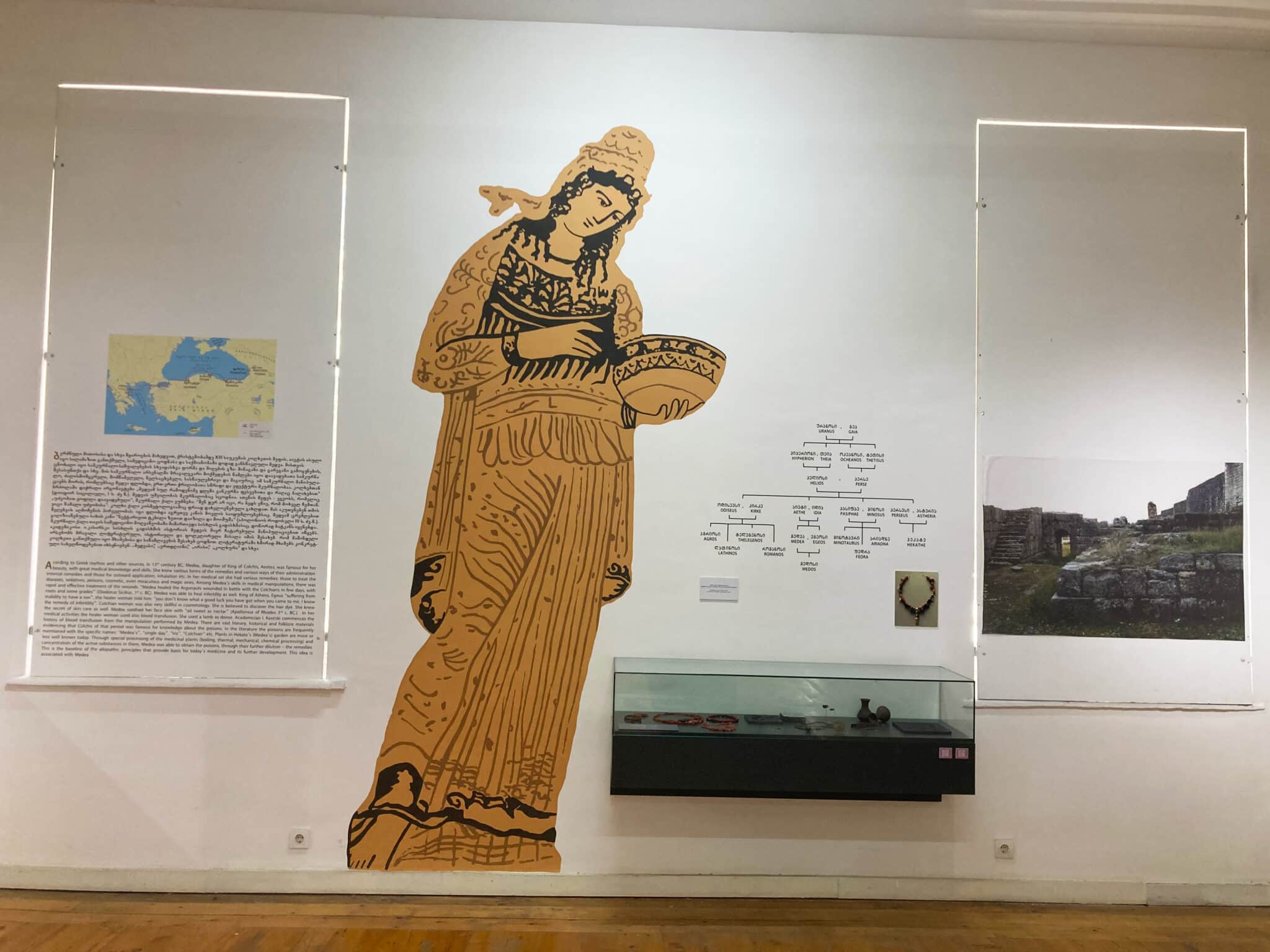

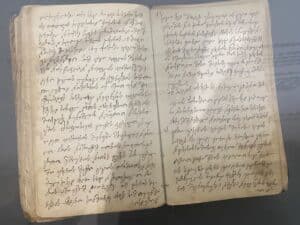

The symbiotic relationship between the evolution of Caucasian medicine and Orthodox Christianity also contrasts with contemporary trends that pit religion and, say, immunization, against each other. This museum showcases medieval Georgian manuscripts written in ecclesiastical script that explain how the proper dose of the right plant-based “poison” can confer immunity from disease.

The story starts with Jason and the Argonauts. Jason was the son of the King of Thessaly, and by rights should have inherited the throne, but his father’s half-brother seized it first. As a young man, Jason returns from childhood exile to get his due. The Greek usurper to the throne says yes, but first you must travel to edge of the world and fetch the golden fleece from the Kingdom of Colchis (now within present-day Georgia). This is a hero’s impossible task, but Jason is aided along the way by friendly gods. He makes it to Colchis, where the Georgian king’s daughter, Medea, falls in love with him.

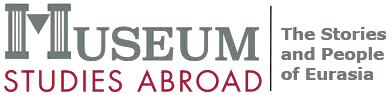

Thus, the museum starts with a full-wall painting of Medea, whose name derives from the same Indo-European root that gives us the word “medicine.” She faces visitors as they enter the exhibit. In the more famous Greek sources, the Colchian princess Medea is described as a “sorceress.” In the History of Medicine Museum, Medea seems more a brilliant scientist credited with knowledge, a museum plaque tells me, of “remedies and various ways of their administration, including internal and outward application, inhalation, etc.”

Her plant-derived ointments and tinctures “healed the Argonauts wounded in battle,” and allowed Jason to achieve his impossible mission. Sources show that Medea was famous for her knowledge of how to use “poisons” derived from plants in such a way that they counter the effects of bodily ailments and disease. Through experimentation and “special processing of medicinal plants,” Medea was able to create specific poisons to remedy specific wounds and diseases. As the museum narrative informs us, “This is the baseline of the principles of allopathic medicine that form the foundation of modern medicine today.” In short, the history of medicine leads back to the Colchian princess who fell in love with Jason and enabled him to get the fleece and return to Greece to take back the throne. Hearing all this for the first time, I had to wonder: “Why don’t we know this?”

Medea is a difficult mother-figure for Georgians. She married Jason, but when they got to Greece, she was rejected as a foreigner, and her medical knowledge was attributed to black magic and unclean powers. Jason abandoned her and married a Corinthian princess instead. Medea’s story has come down to us from Euripides’ play, and it is Euripides’ deranged Medea, shown soaked in blood after murdering her own sons and Jason’s new bride, that much of the world now knows.

In a 2007 article entitled “Medea in the Context of Modern Georgian Culture,” a scholar from Tbilisi University asks “Why are we so anxious about [Medea]? The answer seems simple. […] The phenomenon of a mother, killer of her children, is very difficult to accept for the national consciousness.” But on the other hand, “Medea is a well-known Georgian, closely associated with Georgia’s glorious past.” This scholar concludes that Georgia still suffers from a “Medea complex.” Can Medea’s weaknesses as someone who betrays her own people to help a foreign lover and then murders her own children be reconciled with her magnificent place at the dawn of humanity’s healing arts? In the 1960s, a few Georgian nationalist artists tried to reinvent the Medea myth. But to this day, Georgia’s “Medea complex” seems unresolved – except in the Museum of the History of Georgian Medicine. In fact, the museum has even parked their website at MedeaMuseum.gov.ge.

As my guide and I prepare to depart the 13th century BCE, my guide has been talking for almost an hour already. Understandably, Medea did not leave her extensive, meticulous knowledge of how to use healing herbs and plant-based chemical compounds to the Greeks who had cast her aside. Her medical knowledge was only preserved in the region she came from – Colchis, now the present-day Kakheti region of western Georgia.

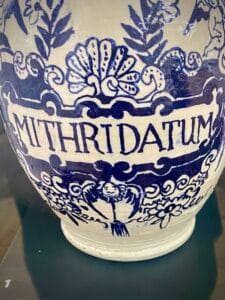

A millennium later, in the first century BCE, another Georgian king, Mithridates, resurrected Medea’s understanding of how “opposites heal opposites.” Plaques along the walls of the museum tell us that this is the basis of modern allopathic medicine – as opposed to “like treats like” (the homeopathic principle). Allopathy takes the more aggressive notion that in order to combat a toxic or debilitating condition, one has to apply the opposite toxin, like chemo for cancer. It’s not gentle, but it saves lives. King Mithridates himself became adept at cultivating Medea’s “plant poisons.” He recorded his findings, leaving a vast library of instructive material. He tried the principle out on himself – to create immunity to various conditions, he used small doses of his own “poisons.” Eventually, when he wanted to leave this mortal life by killing himself, he found that his body’s defenses to poisons was so high that he survived his own suicide attempts.

Mithridates had fought off Roman attacks on the Caucasus, but eventually he lost. His invaluable library went to the Romans, who in this way became heirs to Medea’s wisdom, which ultimately made its way into European civilization. My guide prepares to step into the next part of the exhibit, but first he shows me archeological artifacts of pestles and measuring spoons found in Kakhetian digs, more proof that the history of medicine begins in the ancient history of Georgia itself.

Moving into the 4th century CE, my guide turned out to be as passionate about Mary as he was about Medea. “If you look at the history of Georgia, you see the protective hand of Mother Mary at every turning point.” In the first century after Jesus’s death and resurrection, Mary, my guide says, sent the apostle Andrew to Georgia. Andrew even brought Jesus’s robe back to the Caucasus with him – it’s buried in the Svetiskhoveli Monastery. That wasn’t enough to convert a pagan society, however. In the 4th century, Mary is again credited with sending Saint Nino to Georgia to preach Christianity. Crucially, Nino was also adept at cultivating and using medicinal plants. Her “miraculous” cure of the pagan Queen was not magic, but a well-considered dosage of plant-based compounds. Nevertheless, it convinced the Georgian ruling family to convert to Christianity.

Monasteries founded in Georgia became centers of healing. For centuries, people in need of medical care received help for free in the monasteries. The Museum has a display case of medical texts from the 13th century, handwritten by monks. One of them is actually a veterinary guide on how to use medicines to treat horses. According to my guide, all of Georgia’s most important rulers were also experts in Medea’s arts and deeply committed to Orthodox Christianity’s role in healing the sick. It flashes through my mind, once upon a time, the mark of a successful leader was the ability to provide the people with free health care.

Leaping forward in time again, I learn that the Museum of the History of Georgian Medicine is now racing against time to preserve knowledge of the medicinal plants that indigenous Caucasian people used for centuries. Climate change and lack of knowledge mean that soon the links to biodiversity and healing sources may be lost.

I also learn that the museum was founded in Soviet times by Mikheil Shengelia (1915-1999), ophthalmologist, surgeon, war veteran, and founder of the History of Medicine department at Tbilisi State Medical University. The museum’s collection continues to serve as a training basis and resource for Tbilisi’s medical university, including research on population genetics in the Caucasus. So far, genetic data from the project show that the unique genetic markers of Georgian ethnicity have sometimes migrated outwards and can be found outside of Georgia. But there is no outside genetic material migrating inwards. In other words, a relatively small number of Georgian genes migrate out of the country, but almost no foreign genetic material migrates in. Genetically, perhaps, Georgia is still that ancient kingdom at the edge of the world.

I find this latest fact somewhat confusing in its logistics. However, I find that nearly two hours has passed and I need to leave to attend to other things. While I did not manage to see the second floor, I would definitely recommend this museum to anyone interested in seeing an unusual and fascinating history that can change how you see the world around you.

A Pseudo-National Museum Seeks National Validation

By Jaime Wise, University of Richmond

The Museum of the History of Georgian Medicine, only a seven-minute walk from the Marjanishvili metro station, is a small museum with a massive cultural footprint.

Locating the museum is a difficult task: look for a sign in Georgian, pointing in towards a courtyard, with an anatomical drawing of a knee on it. Inside the courtyard, the museum is the first building on the left. The entrance is on the furthest side from where you will be standing, but, once you get there, there are multiple signs in English that will indicate you have found the right place.

The regular entrance fee is 10 GEL, though a guided tour in either English or Georgian is available for 25 GEL. I asked for a guided tour but was only charged for a standard ticket and quickly left alone in the exhibition space. If you want a guided tour, ask very clearly.

The museum has three floors, only two of which are actual exhibition spaces. Its small size belies its 19,000 artifact collection, amassed over the course of forty archaeological expeditions across Georgia since the museum’s inception in 1963. During the Soviet period, the museum and its collection were housed at the Blue Monastery. After Georgian independence, the monastery was returned to its original religious function and the museum moved to its current location, which was built as a nursing school in 1872 and today is one of Georgia’s official monuments to its cultural heritage. The new location is more thematically appropriate, though its historic status likely explains the museum’s awkward placement.

The first exhibition floor functions as a pseudo-national museum. A number of artifacts on display have no provable connection to medicine: they seem to have been uncovered over the course of excavations authorized by the museum, consequently becoming the museum’s property despite not conforming to its subject matter. The most unusual of these artifacts is a tablet containing text from an unidentified writing system and language. To me, this was worth the price of admission.

The artifact descriptions – written in understandable but admittedly broken English – that actually pertain to medicine cover thousands of years of history incredibly quickly. This is not a museum of medicine as much as it is a story about Georgia told through a Georgian lens. The first display visitors are faced with is three quotes, all by Germans, describing the physical superiority of people from the Caucasus. Of the three, only one mentions medicine. Together, however, they offer outside validation for the deep national pride that spawned this museum.

Georgia is a small country that has spent much of its history under occupation by a revolving door of empires; consequently, they celebrate persistence and any part of their long and messy history that can be called unequivocally Georgian. One of the two men staffing the museum gave me a brief introduction on the first floor (although I had not paid for a tour) and pointed to a display case containing sharp tools for puncturing bone. “Trepanation was invented here in Georgia,” he told me, referring to the ancient practice of cutting a hole in a person’s skull to alleviate pain. He may have meant that trepanation was invented independently in Georgia, uninfluenced by any invading force, not that Georgia was the first place in the world where the practice was discovered. This distinction was not clear to me, but it matters deeply to understanding the purpose of the museum.

This is the Museum of the History of Georgian Medicine, not world medicine or human history, but if the museum employee was truly saying trepanation was born in Georgia and disseminated to the rest of the world (and I believe he was, though that claim is easily disprovable with a quick Google search), that statement complicates the supposed message of the museum, contradicting the purpose its name implies it carries before visitors even walk through the front door. The museum employee’s misplaced pride reflects the same need for external recognition and significance to the world at large as the German quotes, which, in their position at the entrance, serve as a sort of thesis statement for the museum.

The second floor is less abstract and more committed to its depiction of Georgian medicine within Georgia. It primarily covers the 19th century into the mid-20th century, with no reference to the present. Most of the artifacts were donated by members of the Georgian Medical Society, a group of medical professionals that was heavily involved in the creation of the museum, and though the narrower scope and proximity to the present makes the artifacts on display feel less sparse than the first floor, the line between wider medical history of the period and the history of the Georgian Medical Society is blurred. The most immersive part of the exhibit is a replica doctor’s office, compiled from donations by famous Georgian physicians. Each doctor is identified by name, replacing the national pride of the first floor with individual pride from GMS members on the second.

Logistically speaking, there is a very high likelihood that you will have this museum to yourself for the course of your visit. I enjoyed being able to move at my own pace and see artifacts from different angles without having to wait for anyone else to move along first. You will need internet access to have the full experience, however, as the museum does not have wifi and most display cases have QR codes that direct to videos in Georgian or English (read by an AI voice) that add crucial information for understanding the artifacts inside. I found the museum visually appealing and the layout intuitive, both of which contributed to the sense that the two exhibits were each telling a story, though they do not feel connected. If you have a free hour, The Museum of the History of Georgian Medicine is a worthwhile visit, though more for its fascinating view of Georgian history than a comprehensive overview of medicine.

You Might Also Like

Igrika Crafts: Interactive Art in Tbilisi, Georgia

Igrika Crafts is a family-run art studio based in Tbilisi which specializes in block-printed textiles with traditional Georgian folk motifs. They graciously offered to organize a block-printing workshop for my fellow SRAS Tbilisi study abroad participants to teach us more about their art as well as the Georgian history, culture, and folk art which inspires […]

Maia Tsinamdzgurishvili: Elevating Silk Threads to Art

Maia Tsinamdzgurishvili is a modern Georgian textile artist living and working in Tbilisi. I had a chance to visit with her in her apartment in Tbilisi in the hopes that I might learn not only about her own work, but about the state of modern textile arts in Georgia. During my time with Maia she […]

The State Silk Museum in Tbilisi, Georgia

The Georgian State Silk Museum celebrates and supports sericulture (the process of making silk) as an act of biology, engineering, handicraft, and art. Its displays take you through the lifecycle of the silk-worm to the gathering, weaving, and dying of silk threads to the final cultural products sericulture produces. The facility also hosts a reference […]

Soviet Mosaics in Georgia: Controversy, History, and Fascination

I can’t put my finger on what sparked my interest in Soviet-era mosaics, but at this point, I’m obsessed. As someone who grew up in the US, it’s a rather foreign thing to see the sides of entire buildings decked out in brightly colored scenes made of tiles. It also contradicts what many people believe […]

Stalin Museum in Gori, Georgia

Gori, located a ninety-minute drive from Tbilisi, may not catch a visitor’s eye at first. However, the town is forever cemented in history as the birthplace of one of the most well-known leaders in world history: Joseph Stalin. Born Ioseb Jughashvili, Stalin spent the first sixteen years of his life in Gori. While Gori hosts […]