Socialist Realism was the official artistic movement of the U.S.S.R. It was attached not only to the revolution but to the forward momentum of the communist ideology and Soviet apparatus. As an artistic movement it is still a controversial topic. It is also a difficult one, because so much is encompassed in the concept. At its worst, Socialist Realism produced, even demanded, empty propaganda. At its best, it produced artworks pulsing with life, with immediacy and potency. Whatever its successes, it is impossible to view even the most creative and moving pieces from this period without handling in some way the subject of repression.

The movement was irrevocably attached to the Wanderers’ aesthetic of the 19th century. Both movements had, at least in rhetoric, an eye to social realism – both were ‘art for a purpose.’ However, this second wave of ‘art for a purpose’ came after the contemporary artistic world had turned to new ideas and aesthetics. In the early 1900s, the Symbolists and abstract painters had begun a movement in almost the exact opposite spirit. With their stylization, formalism, and abstraction, not only did they reject Realism but many also proclaimed that art should be for art’s sake. This artistic explosion took over not only the worlds of painting, but those of Theater, writing and book-design as well.

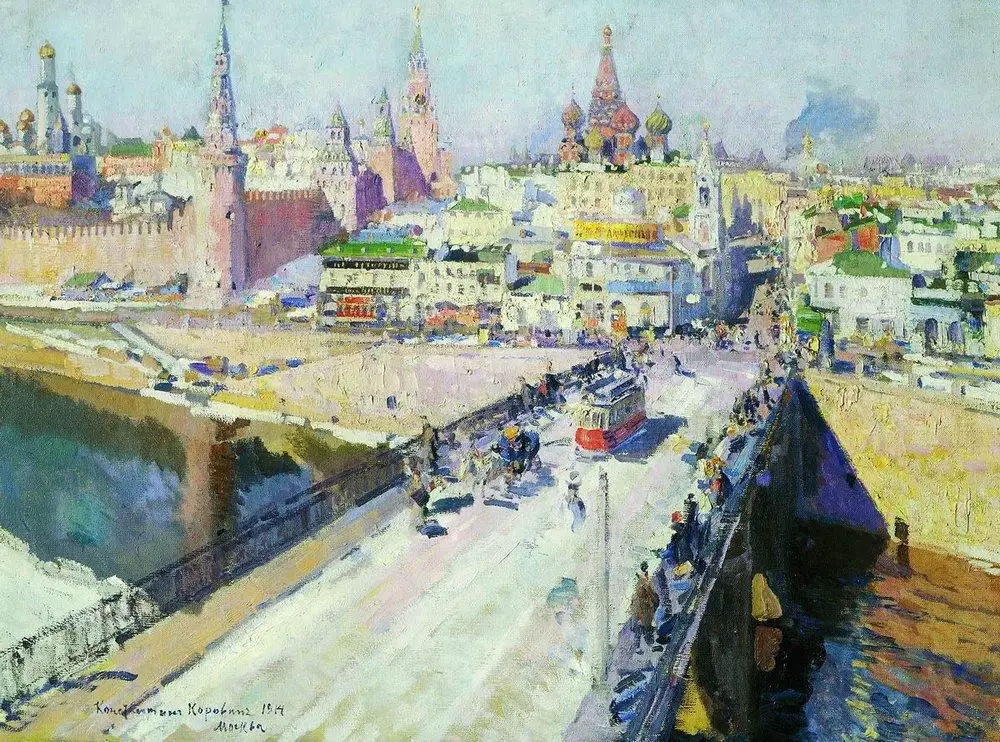

The Realist aesthetic of the Wanderers was also changing on its own: it had become increasingly influenced by the French Impressionists. A prime example is Korovin’s 1914 painting Moscow Bridge.

Following the revolution, various disparate movements sprang up to represent the revolutionary spirit. One of these was the new emanation of the Wanderers –the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR). They underlined their connection to the 19th century Wanderers by holding another Itinerant Exhibit, the 47th , in 1922.

The Socialist Realist tenets began to emerge, but these were surrounded by other waves of expression, openly influenced by the previous two decades. They collected in artists’ unions like The Left Front, the Proletcult and the Society of Easel Painters (OST). These captured the revolution very differently than did the AKhRR, and although ultimately condemned by the Soviets, their ideas still managed to have some influence on the ensuing Socialist Realist style. Many artists who eventually found success within the strictures of Socialist Realism had begun in the twenties with very clear formalist tendencies.

When Socialist Realism was written down as an artistic doctrine in Stalin’s 1928 5-Year Plan, the urge to suppress the artistic experimentation of the early century was made clear. Much of the rejected artwork, which was so consciously unconscious of social concerns, was condemned as ‘decadent.’ Indeed, this term was applied to most art from the previous three decades.

Then, on April 23rd, 1932, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party dissolved all external artist unions – the AKhRR effectively got dismantled and absorbed, while others were forced completely out of work. The Party explained this move by saying that “these organizations might change from being an instrument for the maximum mobilization of Soviet writers and artists to being an instrument for cultivating elitist withdrawal and loss of contact with the political tasks of contemporaneity” (qtd. in Wallach 75). The new, government-controlled unions provided considerable assistance to their members and it was consequently extremely difficult to make it as an independent artist. The All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers took this a step further in 1934 when they defined Socialist Realism as the only true art, effectively out-lawing all “dissident” artwork. When the Academy of Arts was re-established in 1947, it severely limited the way new artists learned to paint as well as their sense of artistic history.

Maxim Gorky called the 1907-1917 avant-garde “the most disgraceful and shameful decade in the history of the Russian intelligentsia” (qtd. in Wallach 75-6) Considering the severe repression, it’s not surprising that many of the most prolific from the avant-garde period fled elsewhere. Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner were among those who emigrated to escape Soviet repression. At the end of the thirties many artists were even sentenced to death or hard labor.

The Realist venture that resulted from this massive overhaul was very different from that of the Wanderers. During the period of time between the April 1932 and August 1934 declarations, upwards of four hundred texts on Socialist Realism were published. Within them it was asked again and again what kind of Realism could correspond to the aims of the movement. Socialist Realism was a fairly contradictory mix of philosophies, which made a definition of its true aims and guidelines deeply problematic. Somehow, unflinching revolutionary zeal would have to be combined with the Realism of the Wanderers, which was based largely on documenting human strife.

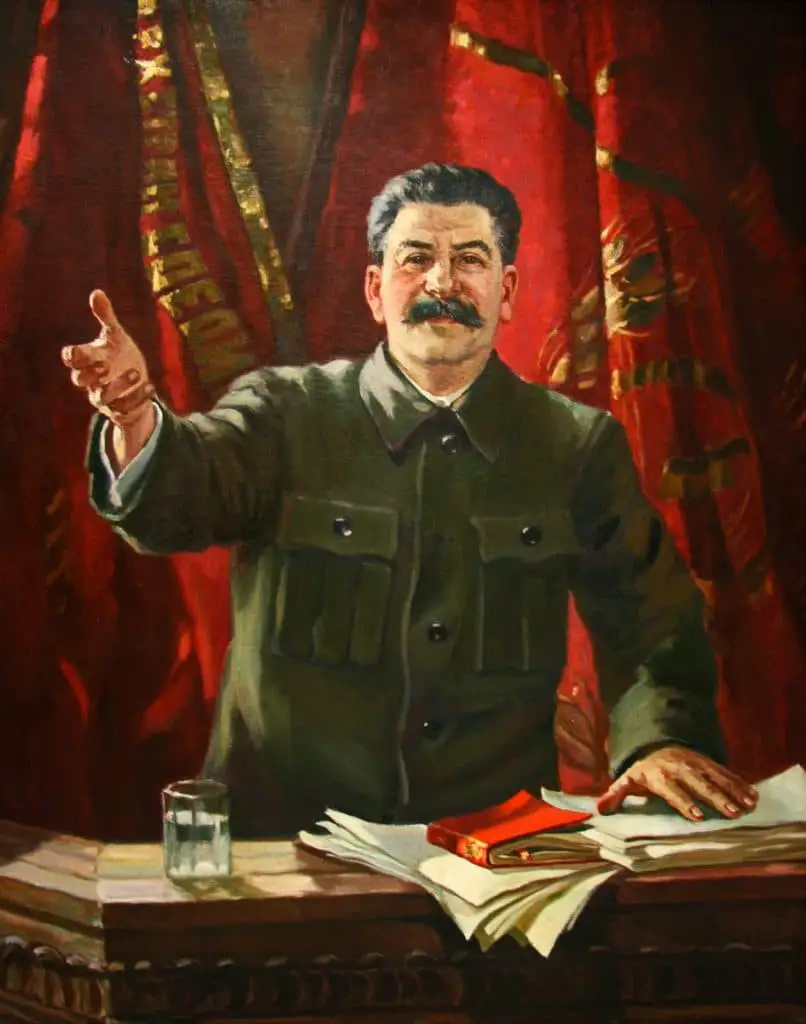

In realizing these aims, artists couldn’t help but draw on some of the emotional stylizations popularlized over the past two decades. Many early-century techniques found their way into major works. In particular, the World of Art’s decorative sense of color and line can be seen in pieces like Gerasimov’s Stalin at the XVIIIth Party Congress (1939).

This movement was not by any means engaged in strictly and naturalistically depicting nature and social scenes. Rather, “naturalism” was condemned from the start. Among those accused of “naturalism” throughout the course of Socialist Realism, were even some of the most famous pieces, with some of the most clearly safe topics. The list includes A.M. Gerasimov’s Lenin on the Tribune and I.I. Brodsky’s Lenin in the Smolny (1930).

Alla Efimova, in “To Touch on the Raw” read through memoirs and writings of the Socialist Realists in order to uncover their artistic concerns. This, she says, yielded “a number of persistent motifs and metaphors that [. . .] have little to do with the official doctrine. One of these is a peculiar understanding of realism where that emphasis shifts from the truthful representation of reality to making the viewer feel real – that is, alive and sensually responsive. This unusual neurological discourse on realism was accompanied by the almost magical incantation of the word ‘life’ (zhizn’) as if to produce the feeling of aliveness was the most urgent desire of the artists and critics” (77). The “real” being captured in Socialist Realism was thus more emotional and intangible than were the social narratives and awe-inspiring landscapes of the Wanderers. It was meant to be a powerful force, evoking Soviet pride. In this way, the movement was at least vaguely reminiscent of the Blue Rose aesthetic, which hoped to bring transcendence through art.

A more concrete element of Socialist Realism was the heavy emphasis placed on theme. The importance of message was understood: it should depict a Communist future and a glorious present. To this end, Russian heroes, contemporary and historical, were commonly depicted. Following the outbreak of World War II, the subjects of the bravery and optimism were frequent, at home and on the battlefield. A work by Laktionov, Letter from the Front, painted in 1947, captures this message. It depicts a family gathered together to happily enjoy news of the war. It also blazes with that “magical” Realism mentioned above.

In an inscription written for the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow, V.I. Antonova describes the artist’s process of capturing the “real” by inventing it: “the action took place on a typical gray day, without sun, but despite the placement of the already found figures which pleased Laktionov, it was not expressive enough, did not capture the viewers. By illuminating the scene with bright sunlight, he found, at last, the perfect realization of his idea” (qtd. in Efimova 78). This luster, not technically “real,” nevertheless shot the painting through with an optimistic feeling of “life” and immediacy.

There are many example which display a clearly monumental, romantic take on Realism. Rylov’s In the Blue Expanses (1918) is an early work, but one considered canonical of the Socialist Realist intent and aesthetic. It’s a landscape painting, but with an allegorical function. and one can detect the same attention to line and color brought into style by the World of Art. Similarly, Yu. I. Pimenov’s New Moscow (1937) displays the still-present effects of Impressionism, albeit supposedly removed from circulation at that point. Deineka’s Defense of Sebastopol (1942) displays not only the Symbolist attentions to movement and line but the Decadent obsession with violence.

Andrei Zhdanov, while secretary of the Communist Party, declared: “Comrade Stalin has called our writers ‘engineers of human souls.’ What does this mean? What obligations does this title impose on us? First of all, it means that we must know life so as to depict it truthfully in our works of art – and not to depict it scholastically, lifelessly, or merely as ‘objective reality’; we must depict reality in its revolutionary development…. Soviet literature must be able to show our heroes, must be able to catch a glimpse of tomorrow” (Wallach 76).

Some say the movement insisted innately on an impossible aesthetic. Art historian Matthew Cullerne Bown, in Socialist Realist Painting, argues that Socialist Realism had contradictory ambitions, which insured its failure as an art form. It inherently leaned on rigid past precedents of Realism in order to theoretically look forward, towards a Communist future. It was an artistic style at least partially-defined by its refusal to create.

Stalin’s death in 1953 made immediate cracks in this system. The period of time under Khrushchev’s leadership is referred to as “The Thaw.” Laws didn’t immediately change, but people began to work around them. The ‘cult of personality’ was derided as a detrimental artistic doctrine and individualism in art began to enjoy a resurgence. After Stalin’s passing in ‘53, the Pushkin museum began showing Impressionist and Post-Impressionist pieces. In 1957, the rules with regard to who could and could not exhibit were altered. No longer were the shows limited to members of the artists’ unions – they were, rather, juried. That same year, a World Youth Festival was held in Moscow, exhibiting international artworks. Many of Russia’s avant-garde painters such as Nicholas Roerich and Robert Falk became known to the USSR painters in the 50s, albeit thirty years or so after their hey-day.

Still, experimentation was harshly criticized and rejected as genuine art. When the first Congress of the Russian Artists’ Union met in 1960, it overwhelmingly reaffirmed the tenets of Socialist Realism. Khrushchev sporadically allowed many changes, but he also harshly derided non-conformist or ‘unofficial’ artists. These artists still generally had to either sell privately to intelligentsia or work in other professions to get by. Many were exported to the United States.

At the Manezh Exhibit (Thirty Years of Moscow Art) held in 1962, Khrushchev famously and virulently criticized many experimental works. In particular, he derided Nikonov’s painting The Geologists for its uncheerful bleakness. Both paintings that were too abstract and those that were too photo-realistic were deemed unacceptable by Khrushchev. He reminded those present that Soviet art had the “lofty mission” to “truthfully depict the life of the people, to inspire people to build Communism, to educate man to the very best, noblest feelings, to a deep understanding of the wondrous. [. . .] A picture should elevate, ennoble man, inspire and lead him to a noble deed” (qtd. in Quest, 26). This event captures the volatility of the era – on the one hand, this and similar shows were sometimes allowed to go forward, but the rules were at the same time unpredictable and harsh.

The Brezhnev era was referred to as the era of stagnation, although artistic freedom continued its slow march forward. It wasn’t until Gorbachev came to power in 1985 and his perestroika reforms were instituted that nonconformist artists stopped being seen as state dissidents.