The State Russian Museum holds the world’s largest collection of Russian art. The approximately 110,000 square feet of the museum’s primary exhibition space are structured to give the visitor a basic overview of how art has grown and developed specifically in Russia. Several auxiliary spaces are used to show everything from folk art to modern art.

Museum History and Structure

The State Russian Museum was founded in 1894 as Nicholas II ascended to the throne. One of his first acts, the museum was meant to honor his recently-deceased father, Alexander III, and was originally named for him: The Russian Museum of His Imperial Majesty Alexander III.

The museum served as a natural foil to the Hermitage, which had opened as Russia’s first public museum in 1852, just 42 years previously. While the Hermitage, then a similarly-sized museum to the Russian Museum, focused on showing a pan-European cross section of great art, the Russian Museum was founded to showcase specifically on Russian art and Russian artists.

The original collections were drawn partly from the Hermitage and partly from various private donations. Its main source of works, however, and its ongoing source of new artwork, was to be primarily the Imperial Academy of Art, founded in 1757 under Empress Elizabeth. New artwork had to be pre-approved by the museum director, who was to always be chosen from the royal family. Further, the artist had to have been a member of the Academy for at least five years. Thus, the museum was to showcase art produced by Russians, respected by the Russian art community, and deemed acceptable by the royal family.

To house the museum, the Mikhailovsky Palace was purchased by the Russian treasury from the royal Pavlovich family. The palace, located within walking distance of the Hermitage, was an interesting choice. Although the museum was to showcase specifically Russian art, the palace chosen to house it was an example of high European classicism, perhaps showing just how deeply Nicholas II saw Russia as embedded in European cultural traditions, even as he sought to emphasize specifically Russian achievements.

The museum nearly doubled its initial collection in its first ten years as private collectors moved to show support for Nicholas’ memorial to his father. Just a few years later, in 1902, Nicholas expanded the museum with a large, purpose-built department of ethnography, completed in 1913. Here, folk art given the tsar by peasants or collected by nobles and gifted to the museum were held. These perhaps most uniquely Russian collections were, interestingly, never publically available. The new building was only opened to the public after 1923, after the revolution. In 1934, the Communists detached the department and declared it its own museum. Today it is known as the Russian Museum of Ethnography.

Like the Hermitage, the Russian Museum saw its collections grow rapidly after the revolution, as private collections were nationalized and forcibly transferred to museums. The communists also built a new restoration workshop to better care for the art stored at the museum. That workshop continues to function today, preserving painting, sculpture, applied art, and folk art.

Most of the Museum’s collections were evacuated during WWII to Perm, where they waited out the war safely.

The museum grew throughout the Soviet period, with acquisitions of art representing all ages and forms of art produced in Russia – and the Soviet Union.

In 1930, the House of Peter I, the oldest building in St. Petersburg, was transferred to the museum. The unique wooden structure, which bears both Dutch and Russian architectural influence, and still filled with Peter’s original belongings, is operated by the museum as a historical monument. Also in the 1930s, the Benois Wing, a separate building meant to be used by art unions and began by Nicholas II, was also given to the Russian Museum. It was eventually joined to the main building with an added vestibule.

The museum’s last major growth came with perestroika and the fall of the USSR. It brought mostly new buildings and grounds. With the collapse of the economy, the government sought to consolidate many historic grounds around the Mikhailovsky Palace. The Russian Museum received the Stroganov Palace (in 1988), the Marble Palace (in 1991), the Mikhailovsky (Engineers’) Castle (in 1994), The Mikhailovsky Gardens (1998), Cordegaardia Pavilions (2001), and finally The Summer Gardens (in 2002), together with the buildings and structures within, including the Summer Palace of Peter I.

In nearly all cases, acquisition by the museum was followed by restoration work and a reopening of the facility as a historical and/or architectural monument and, in most cases, as auxiliary exhibition spaces. This includes the gardens and grounds. The Mikhailovsky Garden, for instance, hosts the annual Imperial Gardens of Russia, an international festival of garden and park art. The extensive grounds display horticulturalist art as well as outdoor sculptures.

The museum has also received two other properties of note. The first is 19 Nevsky Prospekt, now occupied by commercial tenants in what is likely a funding mechanism for the museum. The second is a unique “farm” complex in Pavlovsk built mostly by the Russian architect Andrei Voronikhin. Although now restored, it is not open to public. It is used as a retreat by the employees of the now sprawling museum complex.

The museum today continues to expand – and serve stated government goals to spread Russian culture abroad and unite Russia’s society at home. The Russian Museum has opened a new, permanent space in Malaga, Spain. It also sponsors many traveling exhibitions – such are in Germany and Japan as of the time of this writing. The museum is also working specifically to create “a single cultural space” across Russia. Uniting Russia’s vast and diverse lands has been a challenge for Russia’s rulers since at least the time of Ivan the Terrible. The Russian Museum has so far signed agreements with museums in Murmansk, Samara, Tatarstan, Tomsk, Vladivostok, and Yaroslavl to share its massive collections. Perhaps even more important is the Russian Museum’s work to involve children, students, and people with disabilities in its events and programs. Art therapy sessions, for instance, are offered regularly and many events are designed to accommodate those with disabilities.

All of these goals are also served by the online exhibitions hosted by the Museum: making culture more accessible, breaking geographic barriers, and showing Russian culture as educational and internationally relevant.

Main Displays in the Mikhailovsky Palace

The main focus of the museum remains the Mikhailovsky Palace, which houses most of the permanent display and is conveniently located in central St Petersburg close to the Church of the Saviour on Spilled Blood. Both tours and free, downloadable audio guides are available for the museum. The author of this section had a chance to take a tour with a private tour guide as part of an SRAS study abroad program in St. Petersburg.

Upon entering the large, yellow, imperial-style building, it is clear that the museum sees Russian art as a means to tell Russia’s cultural and political history.

The museum begins where most official histories start Russia’s history: the Christianization of

Kievan Rus’ in 988. At this time, icons began to become popular. The museum’s display shows how icons developed and changed over several hundred years.

Icons were originally meant to tell a unified religious story to the illiterate masses. Thus, there were rules on how to paint an icon, as they were a formulaic religious symbol rather than a portrait. They have no depth, for instance, as they are meant to represent idealized Saints rather than everyday people.

As icon painting spread, different Russian cities created local icons that represented their history and Saints. For example, when Vladimir converted to Christianity he married a Christian, which meant that his older children no longer had any claim to the throne. This resulted in feuding amongst Vladimir’s children which culminated in two of Vladimir’s eldest children killing their younger Christian brothers, Boris and Gleb. This story is represented in an icon entitled St Boris and St Gleb that shows the creation of two new Russian Saints who were canonized in Kievan Rus’ for dying for their faith.

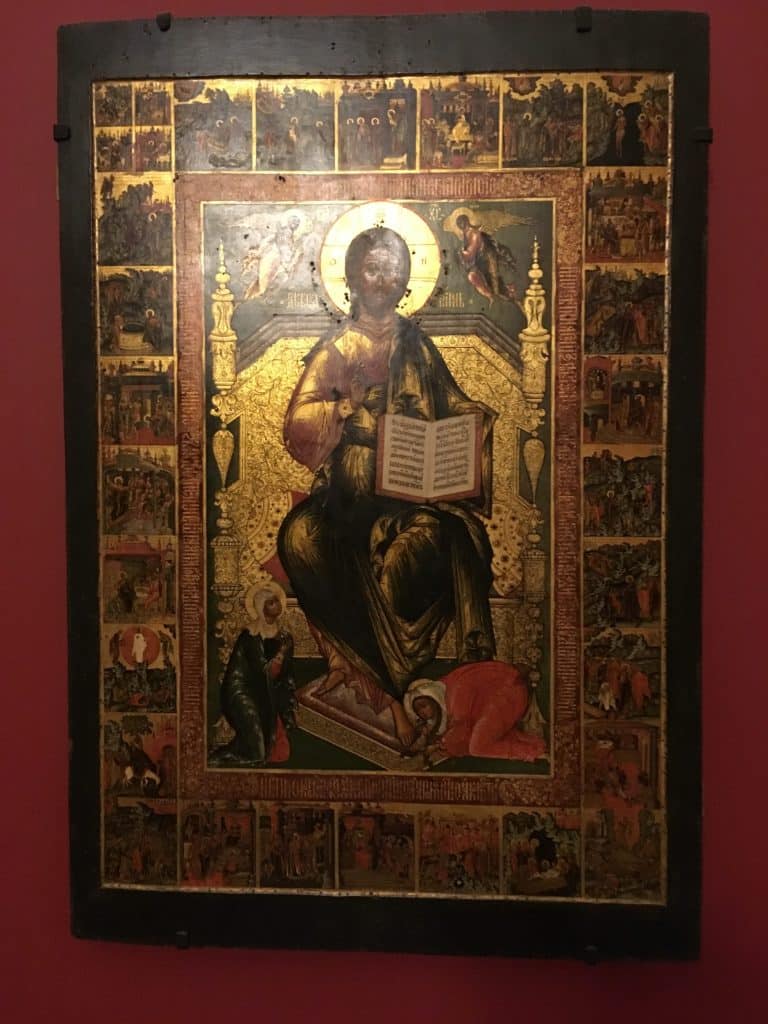

In the next room the progressing exposition shows, more elaborate “life icons,” which depict a saint’s life in small squares around a central image, then evolved. For example, the museum displays the story of Saint George, which began as a folk tale and was later converted to a Christian story. The Saint’s life is depicted around the famous central image of him slaying a dragon. In Russia, Saint George is known for doing this with only his faith. However, since this is hard to depict in a way that common people can understand, he is always shown with a spear that symbolizes his faith.

In the early fifteenth century, icons started to become highly stylized works of art. This is shown in the Russian Museum particularly through Andrei Ruble’s icons Apostle Peter and Apostle Paul, which shows Paul the Apostle and Peter the Apostle holding the keys to paradise. In this image, the Saints no longer look idealized but instead much more like real people.

Icons also became more ornate as exampled by a title-less life icon of Jesus by an unknown author.

Churches and nobles commissioned complicated depictions of Patron Saints which featured gold leaf as a sign of wealth and prominence. Although at first this style was not acknowledged by the Orthodox Church, it soon became commonplace. By the eighteenth century, icons were regularly painted with depth and were frequently overloaded with saints. This style was no longer formulaic and became too complicated for common people to understand. Thus, icons in Russia became an art primarily only understood by the nobility.

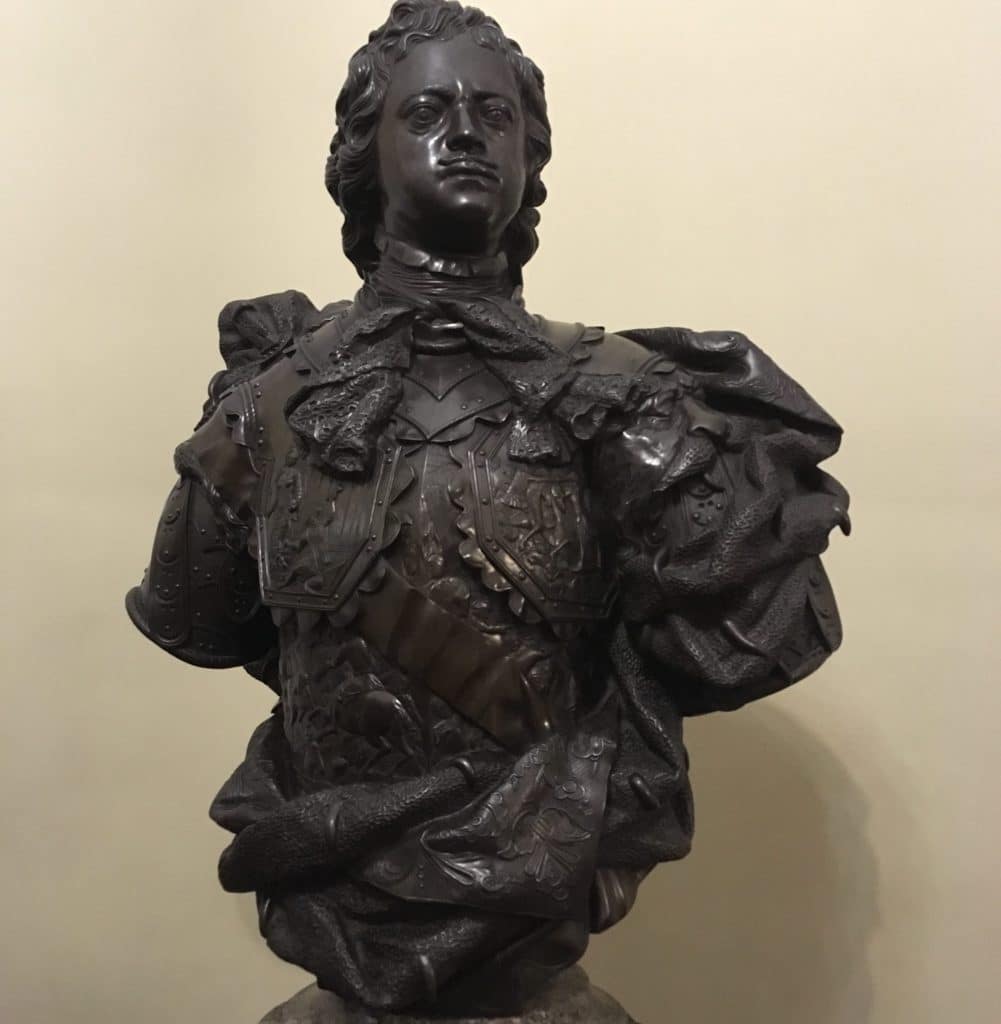

This change was further solidified by Peter the Great who pushed for Russian art to mimic European styles. To do this he brought not only statues and paintings from abroad but also painters to teach classical style to Russian artists. In the next room this style is evident in an ornate bust created for Peter the Great where Peter is depicted as a Roman officer. The bust features various small scenes that are allegorical for Peter building a “new” Russia.

Furthermore, Peter reintroduced mosaics back into Russian art. This is exemplified in a mosaic entitled Portrait of Catherine II by the UST-Ruditsky factory of Mikhail Lomonosov. Originally associated with paganism, Peter’s liberalizing and secularizing reforms brought it back to popularity. Today, various Russian cathedrals and cemeteries prominently feature this style of art.

Despite Peter’s reforms to art, there was still continuity of the style once reserved for icons. For example, on display in the next room, the art created while Elizabeth I was in power was not complicated or allegorical. Most portraits that were commissioned by her were displays of wealth that were heavily influenced by the icon tradition. In the paintings during her rule, like in icons, people were usually depicted as flat with elongated bodies. An example of this can be seen with the painting entitled Portrait of Peter III by Antropov Petrovich. In the painting Peter’s face is depicted similarly to how Saints were painted in icons with a soft expression and almond shaped eyes. Furthermore, the painting is flat and Peter’s body is stretched almost the entire length of the painting, like Saints were depicted in icons.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, Catherine the Great reintroduced allegory into Russian art. This is change in art is on display in following room. For example, in a statue she commissioned she insisted on having herself depicted with the Russian legislature as a symbol of her being a legislator. She also featured a horn of plenty by her feet to symbolically figure her gratefulness that the people of Russia were building a “new” country with her. In a painting on display, Catherine is depicted as burning poppies which was then considered a symbol of pleasure. Thus Catherine is symbolically sacrificing her pleasure for her people. Both her and Peter depicted themselves as liberalizers of Russia, which translated into the art that was depicted during their leadership.

In the nineteenth century, a group of art students refused to finish diploma work which would have required them to spend years working on religious paintings. Instead, they wanted to focus on painting images of living people. For their refusal, they were expelled from the Imperial Academy of Arts. This group later travelled all over Russia and became known as Передвижники, which is often translated into English as “The Wanderers” or “The Itinerants.” Their work represented a shift in the purpose of art in Russia away from a device to convey a religious or approved political message but as one to educate people and critique society.

The unofficial leader of The Wanderers was Vasily Perov. His artwork is displayed in the next room of the State Museum. One painting by him entitled: Monastic Refectory demonstrates the tension between everyday people and religious figures in Russia. In the painting the monks are depicted as greedy individuals who would rather provide for the rich than tend to the poor.

In the nineteenth century, arguably one of the best known Russian painters, Ilya Repin, began producing thought-provoking and often socially-minded images. Due to his notoriety in Russian art the following room is dedicated solely to his works. His best known work, Barge Haulers on the Volga, is on display in the State museum. His work was meant as a condemnation of profit from inhuman labor conditions and depicts people paid to drag the ships to shore. Although many of the figures are presented stoically and even accepting of their fate, one man stands out. In the center is a brightly colored young man that appears to be fighting against his leather binds. This is another use of symbolism and meant to show Repin’s hope for changes in the future.

At the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, Russia saw the start of two divergent streams of art, the first being art inspired by the West and the second looking to Russia’s past for inspiration These streams are shown separately in the two following rooms of the museum. The paintings inspired by Western European art mostly took the form of impressionism, an art form that aims to capture a brief moment in time. For example, Konstantin Korovin’s Portrait of T.S. Lyubatovich shows a girl absorbed in reading her book, aptly depicting a fleeting moment in her life. This painting, like many impressionist paintings by Russians, could be easily be confused with French art.

Alternatively, other artists looked to the people in Russia as sources of inspiration “unspoiled by European civilization.” For example, Andrei Ryabushkin used pre-Petrine society as a source of inspiration in his painting Seventeenth Century Street on a Public Holiday. The painting depicts a moment after church service when people are returning home on the dirty roads. All the people are presented as happy as even the beggar looks to be enjoying himself. For this type of art it was not important how people actually lived but how the painter viewed their lives. This is symbolically figured by the water in the puddle being brighter than the sky it reflects, a symbol of looking back on the past positively.

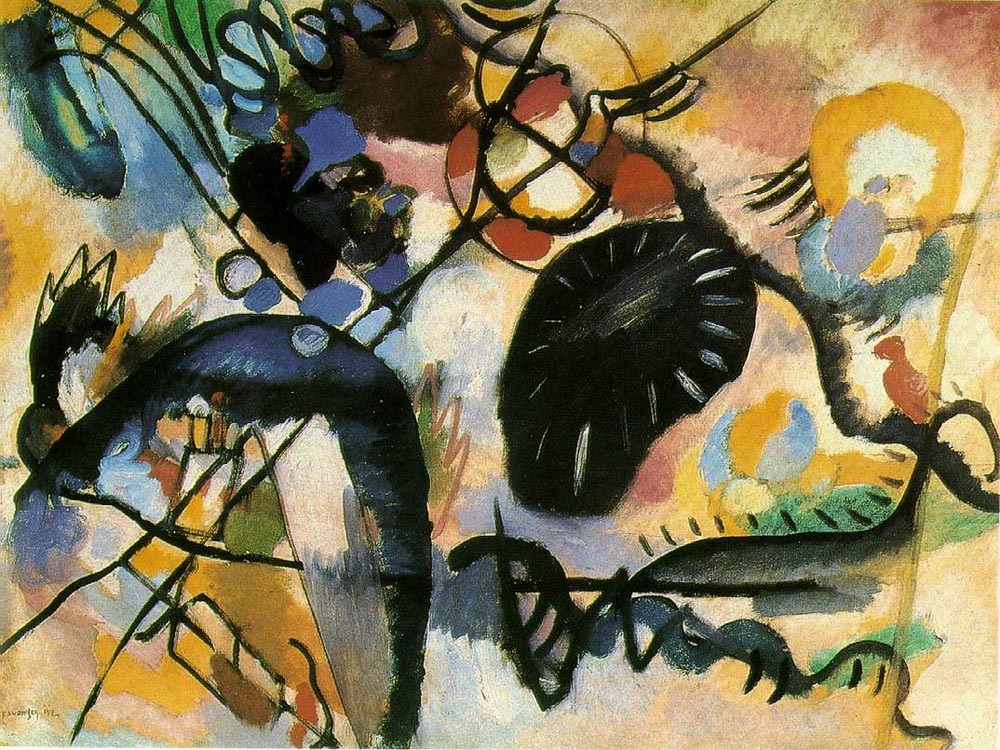

In the twentieth century, Russian art became highly experimental and unorthodox with the avant-garde movement. These pieces of art are shown in the next room of the State museum. Although historically Russia had been following the West, with the avant-garde, it was ahead of its time. This type of art is not simply made to admire but made to garner a reaction from the viewer.

An example of Russian avant-garde art can be seen in the Black Spot I by Vasily Kandinsky. This painting is highly interactive and requires analysis. Upon closer inspection one can see a church with onion domes, a man, a bird, and a ship. However, without looking closely the painting looks like a complete improvisation of shapes without intent.

During the twentieth century, Russia saw the rise of suprematism and constructivism. Suprematism places emphasis on geometrical forms like squares, or circles, as ideal forms with no apparent end or beginning. This expanded into the depiction of faceless people with absolutely no features, which reflected the ideology of early communist times that viewed people as bolts in one big mechanism. This style of art became popular not only in Russia but also in the rest of Europe. On the other hand, Constructivism was a style that was purely Russian and did not really spread to other countries, although it did influence a number of other movements. This art is defined by the use of multiple geometric forms to show how things work or are composed.

The final room in the museum places emphasis on Russia’s movement towards Socialist Realism. This style was introduced after the revolution, as revolution always brings something new. Although at the beginning of the Soviet era, art was highly experimental and thought-provoking, soon communist leaders would place it under strict control. Art was then used as a model through which Soviets could construct the new idealized individual. This style of art, Socialist Realism, was defined by paintings depicting, often contradictory, everyday realities of life in Russia while simultaneously gesturing to Russia’s great utopian future.

The State Russian Museum is an important monument to Russian art in a city that was once built by Peter the Great to be a “Window to the West.” This can be seen in the European style of architecture in the relatively new Russian city. Thus, by devoting an entire museum to Russian-made art, the museum celebrates the value of Russian’s telling their own stories. The museum stands as an interpretive history displaying various points of view on the question of Russia’s national identity, politics, and more.

The State Russian Museum

4 Inzhenernaya Street, Saint Petersburg

Hours: Friday to Wednesday 10 am – 6 pm, except Thursday 1 – 9 pm, and closed on Tuesdays

Price: Adults 450 RUB, Students 200 RUB, Audioguide 300 RUB