Suprematism was an artistic and philosophical movement that drew inspiration from the philosophically non-objective, geometric, and technology-focused Futurism as well as the geometric, depth-focused Cubism. Most strikingly Suprematism opposed art for political or religious utility, and even art as a depiction of the objective world. For the Suprematists, art was produced for its own sake and basic sensations it produced. Art was also a way to explore space and reality beyond ordinary human perception and to seek truth by using creative intuition and non-objectivity.

Suprematism was part of a flourishing Russian avant-garde movement in Russia in the early 20th century. These artists attempted to revolutionize art and with it society.

Defining Suprematism

Russian-born Kazimir Malevich germinated Suprematism in Moscow in 1913 with a black square. By painting this simple shape in oil paint, stark upon a white background, Malevich wanted to transform the dreary realistic world into something infinite and therefore freeing.

Malevich went on to adapt the Futurist use of color to imply movement and to emphasize two-dimensional forms against white backgrounds. He emphasized sharp borders and the dynamism of single hues to draw attention to shapes which were otherwise parallel or diagonally aligned with the canvas.

By 1915, multiple Russian artists had joined him in his experiment and launched the Zero-Ten exhibition in St. Petersburg, a collection of oil paintings that is recognized as the first official Suprematist exhibition.

Other Early Suprematist Artists

Suprematist ideology spread to other artists and to other mediums. Most of these artists worked under or with Malevich at the Vitebsk Artistic-Practical Institute and were part of and/or helped to create in 1920 the Malevich-led group of Suprematist artists UNOVIS (Affirmers of the New Art).

Olga Rozanova, for instance, worked as an illustrator for Futurist poet Alexei Kruchenykh, blending prose with image. Many of the avant-garde saw the philosophy of art as naturally extending to other areas of life, including language. Malevich had, in fact, collaborated with Kruchenykh and others to write a Futurist manifesto against meaning in language before he developed Suprematism. Rozanova painted her subsequent Suprematist shapes with varied colors, weight, and almost flocking movement across the white canvas.

Cubism-influenced Nadezhda Udaltsova integrated weighty, heavily shaded Suprematist shapes into her often architecturally-inspired paintings and drawings. She also collaborated with Rozanova, Liubov Popova, and others to apply Suprematist designs to textiles embroidered by local women weavers. This was a practice with Suprematist design that had even preceded the more officially Suprematist Zero Ten exhibition (Udaltsova, 1916).

Suprematist shapes on clothing and accessories were meant to universalize a non-objective perception of the world. Each of the collaborators had their own style for achieving this. Udaltsova structured her Suprematist textiles and appliqué to bold, dynamic clusters. Popova attempted to transfer the architectural planes of her Suprematist canvas to embroidery with lines hinting at shade and pattern. Rozanova applied bold and linear, rhythmic, and maze-like embroidery.

The Futurist Ivan Kliun, as an eventual collaborator with Malevich in 1916, was less influential in Malevich’s development of Suprematism as he was himself a slow and incomplete convert to Futurism and Cubism, but adopted Suprematism from 1915 and to both the movement and Zero Ten contributed paintings. His oil paintings alluded to sculptural, spherical arrangements of shapes with texturally rougher, almost illuminated shapes upon the white background.

Nikolai Suetin was closer to Malevich’s and the UNOVIS’s philosophical discussions of Suprematism. He applied architectural weight and depth to his own Suprematist works in oil paint, using simple colored shapes on white. He also applied Suprematist forms and reliefs to practical products such tea sets and decorative miniatures as part of his work at the State Porcelain Factory products in the 1920s. We would be joined in his work there by fellow Suprematists Ilya Chashnik and Lazar Khidekel in creating practical objects from idealized forms.

From about 1919, El Lissitzky adopted Suprematist values and styles into lithograph propaganda posters and eventually developed his own multi-media and more delicate three-dimensional style of Suprematist painting called Proun. El Lissitzky’s posters utilized severe, moving Suprematist shapes to portray political objectives while Proun used floating geometric shapes above infinite, multi-faceted planes to bridge Suprematist painting and philosophy with optimistic, future-focused, architectural design.

Lissitzky’s use of art as propaganda was a significant departure from Suprematism’s original apolitical values, but Lissitzky and Malevich continued to work together and Malevich himself, while remaining focused on his art of its own sake, participated in many early Communist artistic organizations after the revolution.

Suprematism Changed By Its Later Artists

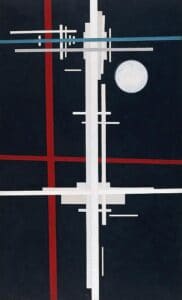

Ilya Chashnik adopted Suprematist artistry into his work after 1918. Chashnik painted oil and multi-medium aerial, geometric forms as structures upon backgrounds of varying and often dark colors, and paralleled or crossed the lines of his constructions with the canvas.

While many Suprematist painters were focused on drawing architectural elements into their paintings, it was Lazar Khidekel who applied the Suprematism to architecture itself, designing a handful of buildings that were built incorporating prominent and often ultimately practical geometric shapes. Khidekel’s Suprematist paintings are clearly buildings incorporating Suprematist geometry and non-objective, precarious and fantastical constructions. Khidekel even attempted to apply Suprematism to practical urban design, utilizing basic shapes and empty space to create flow and functionality within communities.

Khidekel’s reversion to paintings representing the already recognizable may be seen as another departure from Suprematism’s original goals. The movement was, in fact, fairly fluid throughout its history as it expanded and sought to find practical outlets through which it could merge with everyday life.

Malevich’s own art also changed over time, with his later painting still depicting levitating, depthless forms upon a white background, but using the rotation and movement of the shapes themselves to attract the eye, and often displayed solitary shapes or those separated by space. Consistently, Malevich accompanied his Suprematist work with manifestos and theoretical writing expressing how his art explored space and reality beyond human view.

The Rise of Stalin and Fall of Suprematism

Suprematism remained a primarily Russian movement at its height and was largely ended by advent of Socialist Realism under Stalin in the mid-30s. Malevich himself saw the changes coming and sent his archives to Berlin in 1927 for safe keeping. He was arrested briefly in 1930, but later released. He died in 1935. Other major artists either died early in the Soviet era or were later ostracized from the Soviet art world. A few, such as Lissitzky and Suetin, however, maintained their careers and even continued to employ avant-garde elements – but no longer in painting. Instead, they focused on propaganda posters, porcelain painting, and design.

Suprematist influence on later western artistic work in the mid-twentieth century has often been downplayed. This is particularly true of Minimalism, with its focus on blank backgrounds and floating forms and later modernist philosophy of non-traditionalism. Suprematism’s charisma, however, found in its simplicity of form and presentation, makes it still one of the art world’s most immediately identifiable styles.