Constructivism was equally an artistic movement and a social movement. Beginning in Russia in 1915 and ending in the late-1930s, Constructivism stepped away from normal artistic conventions and focused instead on the construction of art with raw industrial materials. Inspired by the Cubist and Russian Futurist movements, it also served as a platform to express the revolutionary and practical goals of the period.

Defining Constructivism

The constructivists rejected the idea that art is created solely for aesthetic contemplation and instead saw their work as grounded as much in science as it was in capturing beauty. Constructivism also drew from cubism’s multiple perspectives and pliable forms and combined it with futurism’s harsh lines and focus on movement and technology.

Perhaps most importantly, Constructivism was grounded in using modern materials like steel, glass, and plastic as art forms. The artist explored how the materials themselves could behave within the artwork, using them to express their physical capacities and allowing them to dictate the final form of the artwork. Unity, beauty, and visual appeal were redefined to incorporate not only the practical applications of the work but also how its form and construction could spark inspiration for new functional designs in manufacturing and social organization.

Given its focus on integration with practical and especially into industrial applications, Russian Constructivism found expression in variety of fields, including typography, fashion, architecture, and ceramics.

Vladimir Tatlin’s Early Constructivism

Vladimir Tatlin, considered the founder of Constructivism, was born in 1885 in the city known today as Kharkiv, Ukraine. An architect, painter, and sculptor, he was particularly inspired by Pablo Picasso’s Construction Still Life (1914), which combined scrap materials into a three-dimensional Cubist relief.

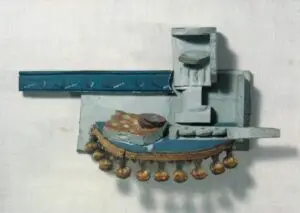

Tatlin sought to blur the lines between architecture and sculpture, presenting “real materials in real space,” and replacing the representational function of art with a more practical one.

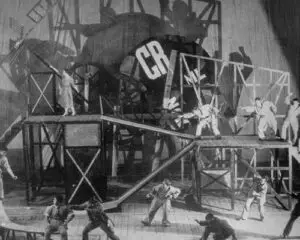

His most famous works are architectural. One, titled Monument to the Third International (1919-20) is an unrealized model for a Communist International headquarters. The design fuses art and technology, aesthetic and functionality to, as he thought, capture the essence of an ideal Communist society.

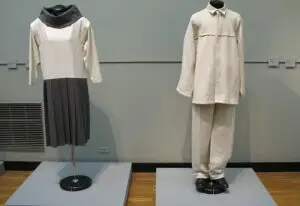

Tatlin also implemented his Constructivist ideals at the Department of Material Culture in Petrograd (1923-5), where he created functional and adaptable clothing designs for the working class. He also redesigned household appliances and furniture so as to increase the efficiency and versatility of these products.

Other Constructivists

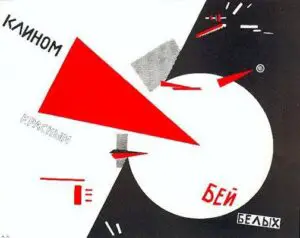

El Lissitzky and Aleksander Rodchenko were important to the development of Constructivist graphic design, which combined simple color palettes and shapes to make bold political statements. Lissitzky also focused on the construction of utopian architecture, like his unrealized horizontal skyscraper, which he argued would have provided better ventilation and more natural movement.

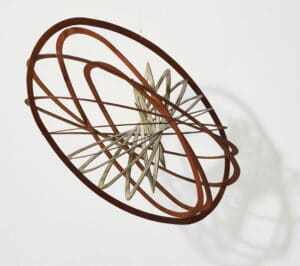

Naum Gabo sought to introduce kinetic movement to his constructivist sculpture. He emigrated to the West at the outbreak of WWI. Today, he is remembered for his unique moving sculptures and credited with introducing the West to Constructivism.

In 1922, Lissitzky brought the movement to the Netherlands where he cofounded the Congress of International Productive Artists and the International Constructivist movement. In the 1920s and 30s, Constructivism lived on in the urban centers of Germany and Great Britain, before eventually making its way to the United States in the 1960s.

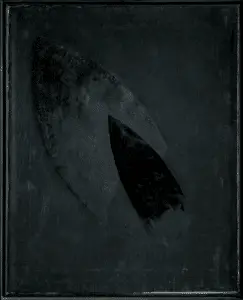

Some of these artists are also associated with the Suprematism movement, which shared some artistic and philosophical elements with Constructivism. Emerging in 1913, this movement aimed to find the ‘breaking point’ at which art ceased to be art. As a result, Suprematism is principally composed of simple shapes, attention to the texture of the paint and canvas, and the use of black and white hues. Many of these elements were borrowed by the artist Alexander Rodchenko, which can be seen in his Black on Black series (1919). A main difference with Constructivism is that, instead of finding the ‘breaking point’ in art, Constructivists wished to ultimately exhibit the fundamental uses of industrial materials.

The role of painting in Constructivism varied greatly by artist. Constructivists reached the consensus that painting was to be eliminated as a medium of art and replaced by sculpture or practical manufacturing. However, Lyubov Popova believed that painting could be incorporated into the movement if such works were used as design drafts for three-dimensional constructions. In other cases, such as in Rodchenko’s Black on Black series, painting was used to make a statement, essentially merging the art with language, something that was also advocated by the Futurists at the time.

Late Constructivism

By the mid-1920s, the popularity of Constructivist sculpture and painting in the Soviet Union began to rapidly decline as the Bolshevik regime began to fight against avantgarde art.

However Constructivism was uniquely positioned to evolve under these conditions. It remained a practiced art form in the Soviet Union by moving outside purely artistic circles and combining with Soviet architecture and with political rhetoric in official propaganda posters.

Given Constructivism’s emphasis on the functionality of art, it is no surprise that this movement has had a long-lasting impact on the modernist era. One of the most notable legacies of Constructivism is El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko’s work with graphic design, typography, and propaganda posters. This graphic design style is known for its eclectic mixture of typefaces, varying sizes, boldness, and serifs often within the same word or sentence. The graphic design of these propaganda posters is known for its use of diagonal elements as well as stark colors, often a dual contrast between red and black. If asked to picture a piece of Soviet propaganda, there is a good chance that such a poster or piece of artwork was comprised of Constructivist typography and design.

Constructivist graphic design can even be seen in today’s pop culture; Barack Obama’s 2008 “Hope” poster by Shepard Fairey as well as the Che Guevara “Revolución” poster showcase the stark color palette and bold fonts of the Constructivist era.

Artists around the world have continued to find inspiration from Tatlin and the Constructivist movement throughout the 20th century. Constructivism remains a fascinating form for artists who wish to continue to push the boundaries of what constitutes art, find ways that art can revolutionize society.