The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center presents a history of Russia through the eyes of its Jewish population, highlighting Jewish contributions to Russian history and emphasizing how Jews have suffered through the same tragedies as the rest of Russia (with special attention to events and policies that particularly impact Russia’s Jewish population). The center effectively portrays Jews as an integral part of Russian history and urges the viewer to consider minorities as populations who should be protected.

The complex, located in the traditionally Jewish neighborhood of Maryina Roshcha, presents more than 2,000 years of history. Although there’s a great deal of reading (mostly in Russian, with occasional English translations), it appeals to a wide audience using 2-D and 4-D films (with English subtitles), photographs, artifacts, and immersive installations. Regular, affordable guided English tours are available for those with limited Russian.

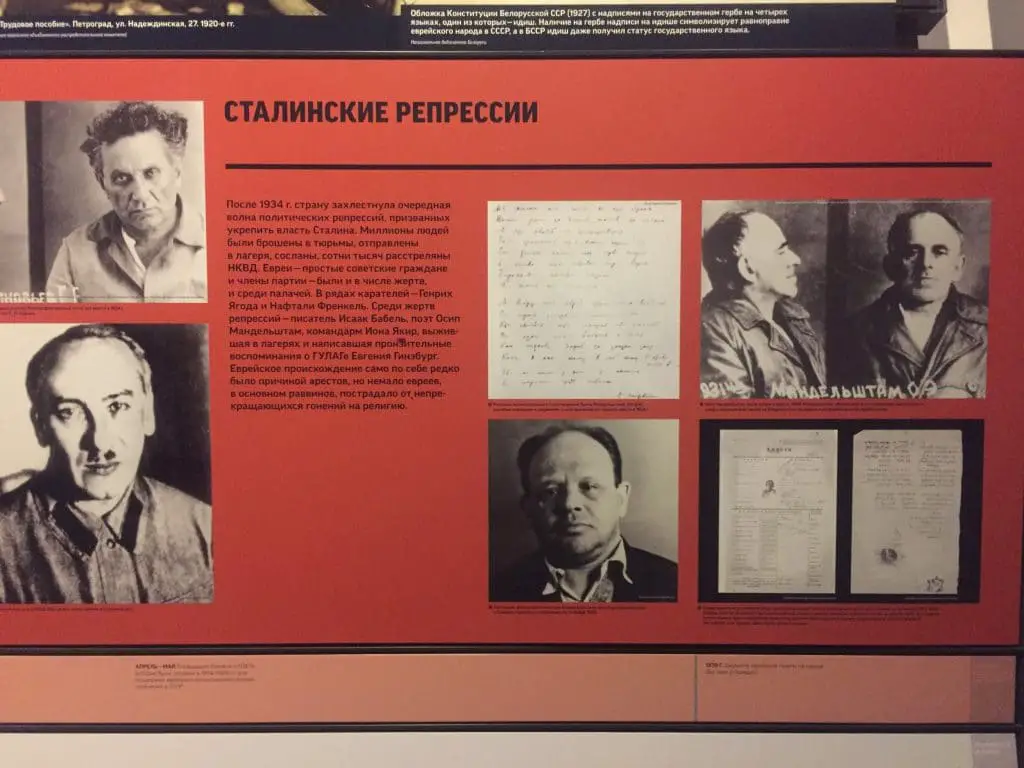

After watching a 4-D film concerning the history of the Jewish people from biblical times until their entry to the Russian Empire, you’re transported into an exhibit documenting life in a “shtetl,” the name given to settlement with a mostly Jewish population in Central and Eastern Europe. The exhibit allows you to explore different aspects of traditional life. A chronologically ordered timeline begins on left wall, running from the 11th century through the Stalinist Great Purges and Great Patriotic War, to which the entire back wall is dedicated. The wall to the right covers post-war to contemporary Jewish life in Russia, giving models of a modern house, birch forest, and a true-to-scale prison cell in the Lubyanka (the famous depository for political prisoners under the USSR). Each of the three walls lead to a film-based exhibition of various roles Jews have played in Russian and Soviet history.

Exhibits tend to feature successes in trade, agriculture, culture, art, and war that portray Russian Jews as a minority integral to the history of Russia and the Soviet Union. This is particularly apparent in the Jewish war effort exhibition, where two large screens show videographies of fighters, and other exhibits show photographs and personal accounts of Jewish fighters and Jewish victims of war. There is a real tank on display as well as a life-size model of a Po-2 plane, famously flown by the all-female “Night Witches,” feared by the Nazis for their deadly bombing raids. Some of these “witches” were Jewish.

As most Russians consider World War Two the defining modern event in Russian history, and as the war and the accompanying Holocaust also strongly impacted Russia’s Jews, it should come as no surprise that this period is the museum’s greatest focus.

It may come as a surprise, however, that The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center challenges the Soviet understanding of World War Two – known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War.

Soviet history generally counts the non-military war dead as one homogenous figure labeled “peaceful Soviet citizens.” Despite the USSR having lost nearly two million Jews to the Holocaust, more than any other country save for Poland, between the Great Purges and the War, the Holocaust is denied its own chapter in history. In fact, as former prisoners of war were often executed by the USSR under suspicion of treason, Holocaust survivors were forced to actively discard that identity and conceal their imprisonment to avoid suspicion. Although this is now changing, the Holocaust has only recently entered public discourse, and there’s no official consensus on how it relates to the greater narrative surrounding the Great Patriotic War.

The museum’s approach is one of bridge-building, presenting the Jewish war losses as unique while not directly focusing on criticizing past interpretations or focusing on any collaboration that occurred within the USSR’s borders under Nazi occupation. The museum also brings Jews specifically into the victory by featuring heroes of the Jewish war effort in the Red Army and partisan movements.

The museum’s mission is solidified in the Tolerance Center, which ends the exhibition. This is an area with tables, tablets, and chairs where you can learn about different minorities and take quizzes about inherent biases. The center also hosts regular discussions and lectures on issues such as tolerance, history, and minorities. Before leaving, feel free to browse the gift shop or stop by the cafe for anything from coffee to a fully kosher vegetarian or pescatarian meal.

The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center was supported by the Kremlin and financed by a handful of Jewish businessmen after Moscow City Hall donated a dilapidated bus garage to the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia in 2001. It first opened in 2008 as the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture and was originally intended to house a cultural center and exhibition on Jewish art. However, the Federation soon decided to take the project in a new direction. They enlisted the help of Russia’s Chief Rabbi, Berel Lazar, to discuss the importance of educating Russians in the spirit of tolerance and celebrating Russia as a multi-national model of co-existence with Vladimir Putin, who then donated one month’s salary toward the project and later attended its opening. Shortly thereafter, the Federal Security Service (FSB, formerly known as the KGB) pledged archival material and primary documents.

The Garage Center then expanded its mandate to include all of contemporary art and moved to a new center, also funded by a Jewish-Russian businessman, Roman Abramovitch, built inside Park Kultury (Gorky Park).

The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, with its new mission and after being redesigned with $50 million in private donations, opened to the public in 2012.

Although the museum is an effective educational experience, it faces challenges making inroads to Russia’s larger society. The history of WWII as written and told by the Soviets is still the dominant narrative of WWII in Russia. Attempts to point to the hardships or deaths experienced by one group are often seen as attempts to diminish the hardships and deaths experienced by Russians and other groups, which were also undeniably substantial.

Perhaps the best example of the challenges the museum faces we experienced as we left the museum. It had started to rain, so we called a taxi to bring us to the nearest metro. As we climbed in, our driver, realizing where we’d been, asked us: “what is tolerance, anyway?”

The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center

Moscow, Ul. Obraztsova 11, bldg. 1А

Sun – Thurs 12:00 – 22:00, Fri 10:00 – 15:00

Closed Sat and Jewish Holidays

400 rubles (200 with student ID)

Guided tours from 300 rubles

jewish-museum.ru