Khrushchev’s reorientation of Soviet life during the cultural thaw of the late 1950s and early 1960s shifted official representations of Soviet people to focus on the more humanizing aspects of life and the everyday: the new Soviet citizen may be a worker, but work no longer defined personhood. Unlike in the Stalinist period, where photography was considered politically dangerous and photographs were replaced by socialist realist paintings, images of everyday life reinforced the cultural program of the thaw, and accompanied the relaxation in censorship after Stalin’s death. Part of the creation of new Soviet identities in the late Soviet period was the depiction of life outside the USSR and Eastern Europe. Ogonek (Little Flame), a popular illustrated magazine akin to Life magazine in the United States, contrasted images of intimate everyday life at home with a barrage of photographs of foreign locales. This process was further facilitated by the Union of Soviet Societies for Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (SSOD). This article will address first how Ogonek and then how union organizations such as the SSOD assisted photography exchanges and represented the Soviet government’s renewed concern in introducing its citizens to life in and outside the Soviet Union.

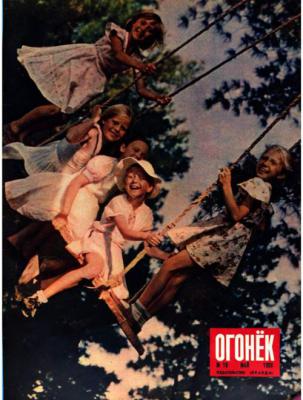

Ogonek was founded in 1899, though it ceased publication during the revolutions of 1917. It was then reestablished by the Soviets under editor Mikhail Koltsov in 1926. In the Soviet period, the journal was published weekly, incorporating vignettes, music scores, reproductions of famous paintings, and, of course, photographs. In terms of importance to the Soviet government, by the 1950s and 1960s, Ogonek reached the widest audience among illustrated magazines, and thus provided a vehicle for helping citizens visualize their place in Soviet society. Yet seemingly paradoxically, by the late 1950s, weekly, sometimes multi-issue,travelogues about foreign countries such as Australia, Morocco, and South Africa, provided readers and viewers a visual record of world events. Color inserts about foreign cities were usually composed of one picture of the city from above, a photograph of either modern or traditional local dress, pictures of sculptures or monuments, and usually only a single photograph of either agricultural or industrial activity, if one appeared at all. Though taken abroad, the images served to reinforce Soviet ideas of self during the cultural thaw. Emphasis on national society and culture, as opposed to industrial output and growth, encouraged Soviet citizens to relate to and value those aspects of their own life, to value a Soviet identity based in both cultural and industrial production. As a result, the number of images devoted to leisure and everyday activities over industry increased substantially (Fig. 1).

The Khrushchev administration was far more committed to opening the Soviet Union to outside visitors and influences than Stalin had been. After operating in a rather closed cultural environment for generations, Minister of Culture of the USSR Ekaterina Alekseevna Furtseva approved a number of international cultural exchanges between students, journalists, and artists, and many of the exchange projects’ owed their success to her initiative. In 1964, she reported, the Soviet Union hosted over 30 foreign artistic groups, in addition to dozens of journalists and photographers. [1] This, in her opinion, was the most successful year of cultural exchanges between socialist and capitalist countries since the Central Committee appointed her to her post in 1960. [2]

Much like cultural exchange programs, journals and newspapers flourished in the post-Stalinist Soviet Union. With one of the highest literacy rates in the world, Soviet citizens hungrily devoured magazines, newspapers, and journals. In 1959, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) Central Committee Commission on Ideology, Culture, and International Party Relations reported that in the first six months of the year, Soviet citizens had spent 550 million rubles on newspapers, journals, and magazines from Soiuzpechat kiosks, one of the largest retail dealers of reading material. [3] In 1974, Ogonek sold approximately two million journals weekly. It represented a significant increase in purchases by individuals, as well as increased distribution of periodicals available for retail sale to the public (as opposed to state libraries and universities). [4] In 1965 the daily circulation of newspapers and journals was projected to be five times what it had been only ten years earlier, and in this case, Soviet figures were not far off the mark. [5] Much of this increase corresponded to the establishment of new special interest journals, many of which depicted life outside of the Soviet Union.

Ogonek and Soviet Photography in the 1950s and 1960s

Ogonek remained more representative of and shaped by the mainstream. As a mainstream outlet, however, Ogonek continued to influence how photographers snapped pictures. Particularly, Ogonek editor Anatolii Sofronov supported photography as an illustrative device, but was not overly concerned about the aesthetic merit of photographs that accompanied articles. Instead, most issues of Ogonek featured one or two “artistic” photographs tucked inside the front and back covers. Most other photographs in the magazine served as documentary evidence to support their accompanying articles. Thus, as Mikhail Koltsov had initially envisioned when he first published the journal in 1926, Ogonek continued to be a periodical for the masses. More and more, the magazine became an illustrated catalogue of the world both inside and outside the Soviet Union, less invested in aesthetics and more interested in mass circulation of easily discernible images that conveyed government interests and goals.

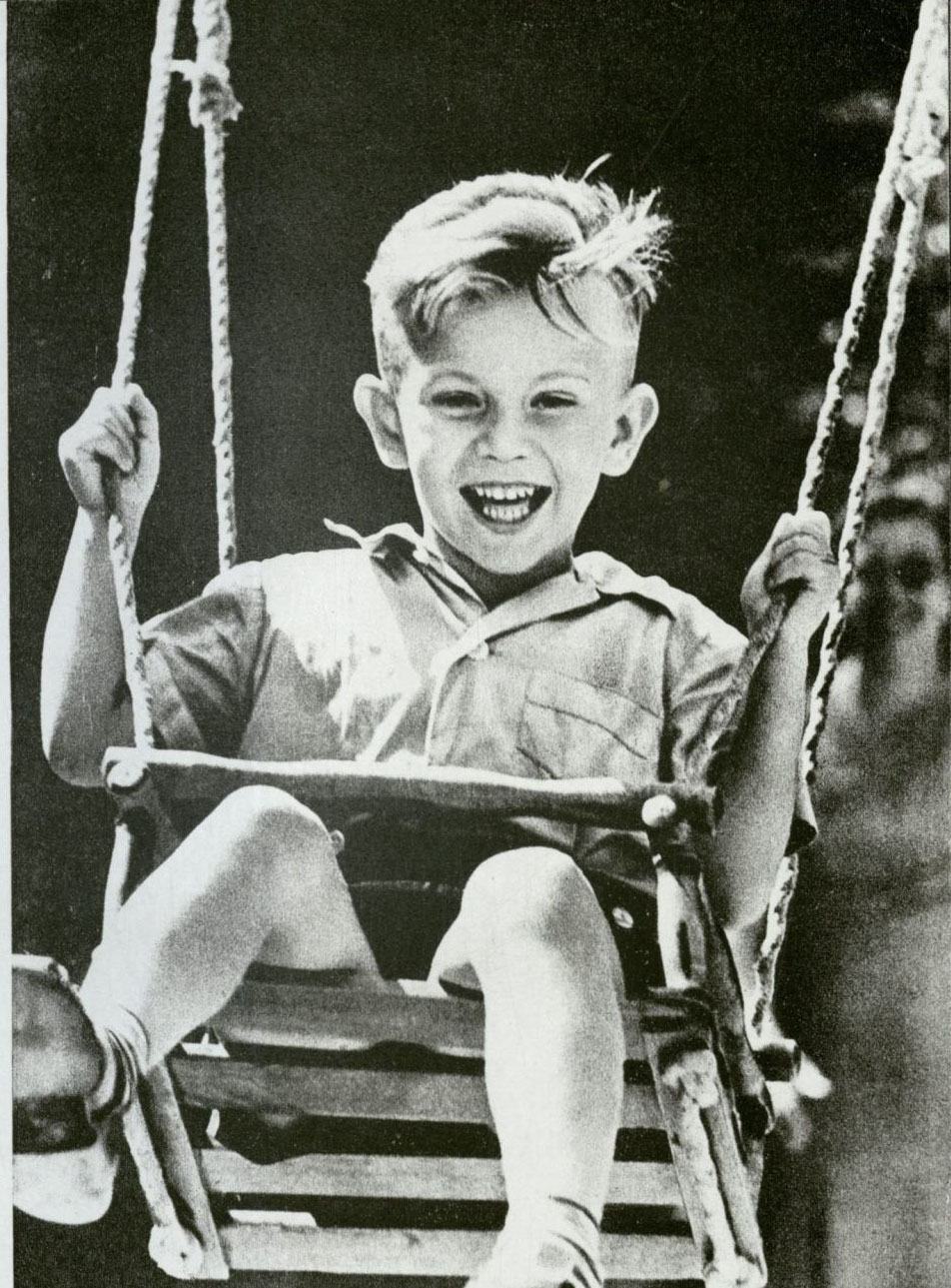

In basic form, Ogonek during the 1950s and 1960s remained much as it had in previous decades. It contained reproductions of paintings, short stories, songs and short musical scores, cartoons, and of course, photographs. But unlike issues published in the 1930s, which documented and praised construction projects, or those published in the 1940s, which were largely about the war and reconstruction, Ogonek in the late Soviet period, beginning in the late 1950s, was much more intimate. While photographs of party congresses, diplomatic meetings and ideologically anti-Western political articles remained, the magazine began to present itself as more representative of the everyday. Photographs depicted women styling their hair, a boy drinking from a glass, or cross country skiers enjoying a winter holiday in the mountains. Articles about industrial projects and five– year plans were replaced by detailed descriptions of a day in the life of a factory or textile worker, focusing as much on their personal life and leisure activities as on their work.

Yet this did not exempt illustrated journals from criticism. Though readers adored Ogonek, its popularity also led to increased government scrutiny. In the early and mid-1950s, up until the last issues of 1957, Ogonek contained very few photographs by comparison to later issues, and these images were usually relegated to the front and back covers. In the early months of 1958, editor Anatolii Sofronov began incorporating more photographs, overlaying various images in the side columns of the journal, providing Ogonek with a very updated and modern look. In September 1958, the Central Committee Commission on Ideology, Culture and International Party Relations issued a serious warning to Sofronov. In each issue the Central Committee noticed there were articles that lacked “aesthetic and educational value.”[6] They specifically singled out aesthetic inconsistencies, inattention to detail, and the editor’s choice of photographs.

There are serious shortcomings in the decoration of the magazine. Your editorial staff has lost all sense of proportion, publishing dozens of pictures on foreign topics without showing the necessary initiatives or artistic taste when selecting illustrations of Soviet life. Many of the photographs that appear on the covers and inserts, are primitive and inexpressive in their execution and are of minor importance on the topic of the article. [7]

Overall, the Central Committee was not disappointed with the choice to incorporate more photographs. Instead, they took issue with the editorial staff, who favored certain topics and journalists. Ultimately, the Central Committee decided that Sofronov should seriously reconsider the content of articles published in Ogonek. The committee also recommended that Sofronov expand the publication’s ranks to include journalists and photographers who would generate more “vibrant” and “exciting” material. It decided that Ogonek should:

Improve the ideological and artistic level of the external design of the magazine. Be more strictly selective of illustrated material, to prevent the pages of the magazine from random, incoherent or irrelevant and slipshod photographs and drawings…We oblige the editorial board to do away with the practice of improper preferential treatment by the publishing staff. Expand the circle of authors, to involve more employees in the magazine industry. Draw material from agriculturalists, prominent scientists, writers, artists…conferences in enterprises, collective and state farms, and educational institutions. [8]

Sofronov took these criticisms into account. He shifted his focus to a mixture of articles about travel coupled with illustrated articles about various cities in the Union Republics and the Soviet Union outside of the capital cities. Information about Soviet political figures was paired with articles about industrial, agricultural, and scientific work, the everyday lives of families, as well as information about exhibitions, artists, musicians and sports. He promoted photojournalist Dmitri Baltermants to editor of photography and divided photography assignments by genre, for instance, assigning particular photographers to sports, others to theater, etc.

|

|

Figs. 2 -3. Cover of Ogonek, March 1959, no. 11(left) and May 1959, no. 19 (right). According to the demands of the Central Committee, Sofronov’s reorientation of the magazine prioritized photographs of the “everyday” Soviet experience.

The Central Committee maintained a relatively strict hand in the dissemination and planning of illustrated journals like Ogonek. While photographers for illustrated journals and magazines were generally spared harsh criticism, editors and magazine staff were not. This was partially because Soviet government officials were not particularly acquainted with the technical aspects of photography and photojournalism. Yet, Sofronov encouraged the incorporation of photographs as the main sources of illustrated material for his journal. In addition to the front and back covers, the editorial staff of Ogonek made the decision to predominantly illustrate three distinct types of articles with photographs: journalists writing articles about everyday life in the Soviet Union;, the feats of the Soviet people (particularly in the periphery of the Soviet Union); and everyday life outside of the Soviet Union were encouraged to utilize photographs as documentary evidence, as a way of adding authenticity to articles.

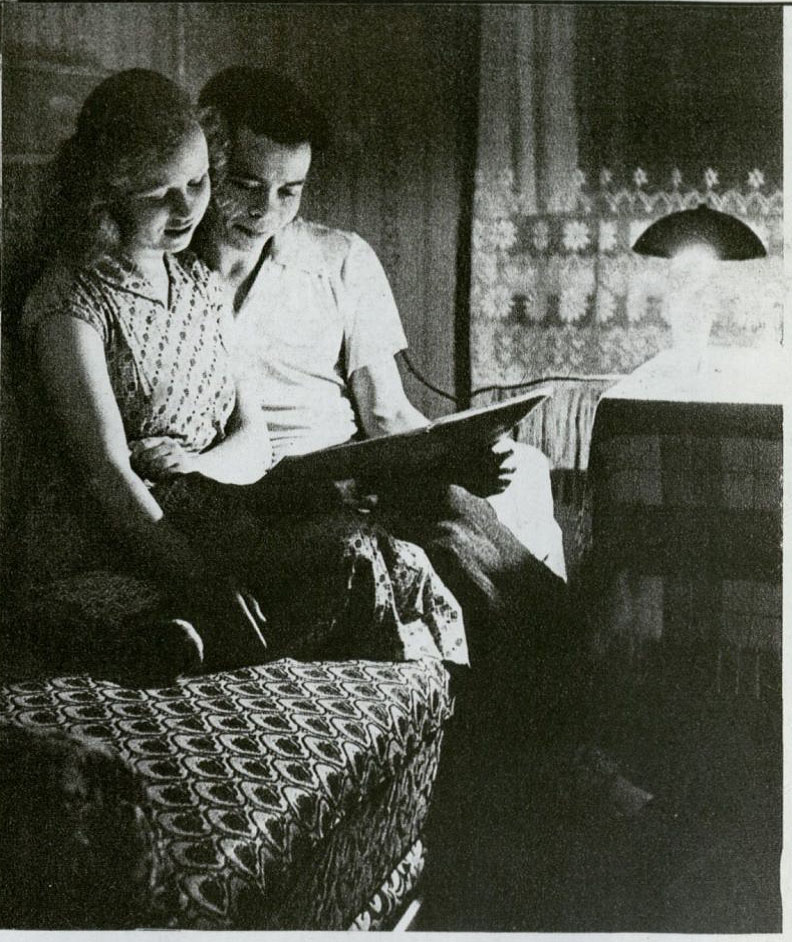

By the late 1950s, then, Ogonek presented its readers a range of articles about Soviet life at home accompanied by photo essays. One such article, in the newly revamped Ogonek, was about recently married young workers searching for housing, entitled “Two Hundred Newlywed Couples” (“Dvesti molodozhenov”). As the article explained, Sasha and Tanya Martianov were accomplished young workers, who desired to move from their factory dormitories into an apartment together. When the young married couple went to the factory housing and municipal department, they were initially turned down. “The newlywed Martianovs were not given an apartment. Why? There was a compelling explanation: Included in the list for housing were some who had worked at the plant for a long time.”[9] The story concludes happily, as one might expect. Despite some hiccoughs in the initial construction of housing for newlyweds, the apartment block was completed in seven months, five ahead of schedule. [10] Sasha and Tanya received apartment number 13, the author of the article taking the time to poke fun at Americans, whose superstitions about the number might have prevented them from receiving the rooms so gladly. [11] Overall, the story represents the type of slice of everyday life that the Central Committee wanted from Ogonek.

Rather than illustrating this type of article with hand-drawn sketches, as might have been done in earlier years, “Two Hundred Newlywed Couples” features not one but five photographs of Sasha and Tanya, their neighbors, and the completed apartment building. Not only did the photographs focus on Sasha and Tanya, but none of the images documented their role as workers or even the construction of their new home. Instead, photographer E. Umnov showed the newlyweds reading a magazine (a copy of Ogonek, as we are told by the author), and Tanya embroidering a table runner with friends from the apartment bloc (Figs. 4-5). The subject of the article, and the accompanying photographs, is the couple, not construction. Photographs of the interior of their finished apartment show a simple yet comfortable space. Put together, the article and photographs speak to readers who may be experiencing their own problems with housing, reinforcing the idea that while there may be delays (just like there were for the Martianovs), socialism was building houses. Furthermore, photographs lent authenticity. Here were Sasha, Tanya and their home. Here they were enjoying themselves. Photography underscored the validity of this ideal, whether or not it was the everyday reality of Soviet citizens.

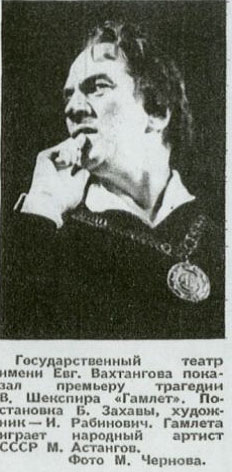

Beginning in the late 1950s nearly every issue of Ogonek contained a small section devoted specifically to photography. The subject and type of photography varied by issue, but two of the more frequent sections were titled “Photographs Tell Stories” (Fotografii rasskazyvaiut) and “Day after Day” (Den’ za dnem). Both featured photographs from around the globe, though predominantly from the Socialist bloc countries. Generally, however, these sections featured “slices of life” and covered a wide range of material, from museum exhibitions, to soccer matches to children playing in parks. Photographs about the construction of an aluminum plant in Stalingrad were placed alongside photographs featuring couples figure skating in the park, a portrait of actor Mikhail Astangov and models of the new Moskvich automobile. The general feeling of these sections was that socialism was as much about aluminum plants as it was about young couples enjoying leisure time (Figs. 6-7).

|

|

| Figs. 6-7. Photographs from the section Photographs Tell Stories. M. Chernov and A. Kon’kov, Untitled, black-and-white photographs, Ogonek no. 8 (February 1958)[12] |

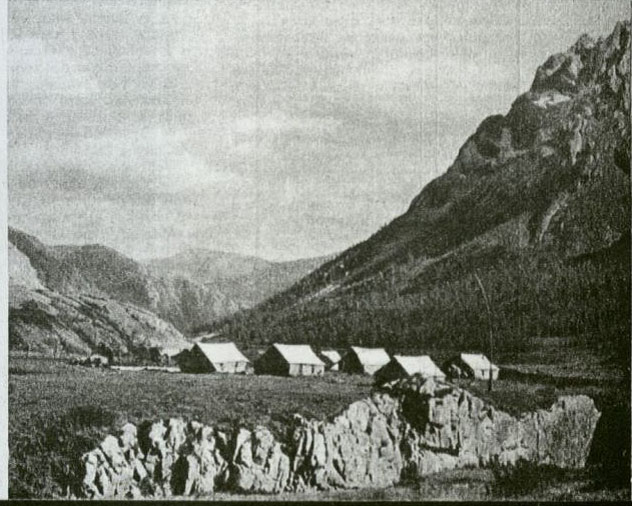

Articles about family and everyday life tended to focus on Moscow and Leningrad, but were accompanied by other illustrated stories about the peripheral areas of the Soviet Union. Often, these articles featured a narrative of overcoming natural obstacles. Articles about conquering the wilderness (and their corresponding illustrations) were an extension and demonstration of the lasting pervasiveness of what historian of socialist realism Katerina Clark describes as the Soviets’ “struggle with nature.”[13] Part of the master narrative of Soviet literature after 1931 incorporated scenarios in which people triumph over their environment to overcome immeasurable odds, and “taming” the wilderness. [14] Iterations of this theme in Soviet literature can be observed time and time again in Ogonek articles. Similarly, Ogonek journalists embraced the socialist realist trope of arctic exploration. Humanity’s subjugation of nature (particularly the far north), a feature of Stalinist literature that remained a major theme throughout the Soviet period, was trotted out at length in novels, short stories, and the press media alike. The conviction that “man alone, unprovisioned, in conditions of extreme cold and in constant danger of attack” reinforced the underlying ideology of the period, that communist ideology allowed man to accomplish what might seem impossible. “In conditions of extreme cold, scientists say that man must die. But these stories suggest that an exceptional man can defy that inevitability,” particularly the Soviet man, strengthened by the might of the Soviet system and its underlying ideology. [15]

A 1961 article about a group of scientists on a geological survey followed this model to the letter. Above the Arctic Circle, they were hoping to find gold and other valuable mineral deposits. Yet, the article itself was not concerned with the success or failure of this aspect of their exploration. Instead the author of the piece focused on geography, and the geologists’ ability to carve out a miniature civilization in spite of the rugged terrain. In three weeks they had put “up a town: tents, storage, a dining room, a bath. The bath was our pride: chopped wood, it was warm as a ‘nuclear reactor’ and there was a stove made of barrels and lined with stones.”[16] Photographs that accompanied articles of this nature likewise followed a sort of template. The emphasis was on creating a livable environment out of that which was unlivable (Fig. 6). The article was not about the results of the geological findings, but providing indexical proof that these expeditions were not only possible, but that the “explorers” were able to live well even in the harshest conditions.

Despite criticisms from Central Committee members, Sofronov was committed to showing the outside world to his readers. Though he increased the number of articles about life and work in the Soviet Union, he continued to prioritize articles about exotic locations to his readers. The content of many of these descriptive articles ranged from verbosity to diminutive. In an article about Jakarta, journalist and photographer Nikolai Drachinskii described “spicy flavors of the rainforest” pouring through open windows, “green giant trees crowding around the white buildings with columns,” and “diamond dew drops hanging on the flowers of orchids.”[17] Photographs of areas outside of the Soviet Union tended first to emphasize otherness, Orientalizing local people and customs, followed by images of locals in modern dress, casting off their otherness in favor of modernity, and in doing so, becoming more like Soviet citizens (Figs. 8-9). Nevertheless, the number of articles about foreign countries suggests that Sofronov and the editorial staff of Ogonek thought it was imperative to show readers what life was like in places such as Indonesia. Although they were discriminatory and oriented towards demonstrating how backwards peoples were becoming more modern (though this is not unique at the time), the presence of articles about people outside the Soviet Union, however heavily draped in slogans and propaganda, gave the average Soviet citizen a look at what their life might have been like had they been born outside of the Soviet Union.

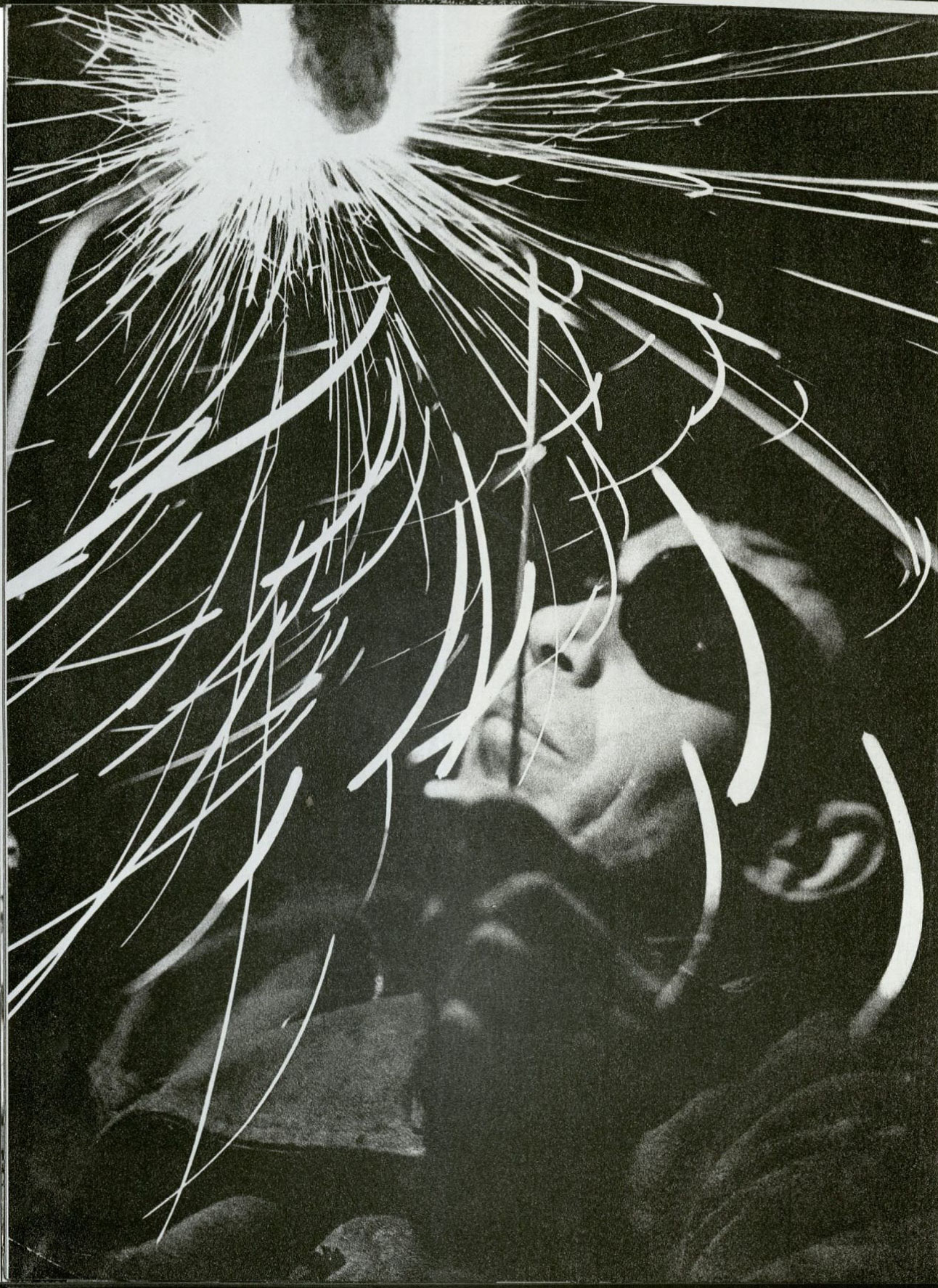

Photographs of everyday activities, interspersed with pieces about exotic locales, dominated the pages of Ogonek in the late 1950s and early 1960s. This is not to say that photographs of industry, construction, and machinery were absent from the magazine. These images were likewise present, but tended to be included as glossy inserts or on the inside of the front or back cover. Similarly, the photographs were not accompanied by full stories, but rather by small descriptions written by the photographer. V. Tarasevich’s photograph of welders appeared in a November 1958 edition of the journal: “In Kharkiv [Ukraine], the country’s largest swimming pool was constructed in the ‘Dynamo’ stadium. In the picture: welders at the bottom of the pool” (Fig. 10). [18] Another photograph, by L. Ustinov, from April of the following year was simply titled “Welder” (Fig. 11).

The SSOD, Foreign Photography, and the Photo Section of the Union of Journalists

As the Soviet Union opened its borders to outside influences, so too, it sought to show the outside world what life was like in the USSR. It became more important for Soviet journalists to participate in diplomacy, particularly as related to journalism and photojournalism. In 1961, one representative at the Union of Journalists received orders from the government to procure journalists and photographers for assignments to international press conferences. [19] The photo section of the Union of Journalists and the photo section of the Union of Soviet Societies for Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (SSOD) often collaborated closely. For example, when the photo section of the SSOD was invited to submit photographs to the 1960 Europaphoto competition, which offered exhibition opportunities for amateur photographers, the photo section wrote to the head of the photo section of the Union of Journalists, Marina Bugayeva, asking her for recommendations and how to contact local amateur organizations. [20]

Many government and Party requests for foreign press coverage and foreign requests for Soviet images landed on the desks of representatives of the Union of Journalists, which by 1960, had on average 122 members on assignment in foreign countries in a given month. [21] The administrators at the Union of Journalists then filed paperwork with the corresponding press agency or newspaper, according to the requests made by the government and Party. [22] These demands ranged from rather open-ended suggestions to very specific requests. For example, the 1961-1962 plan for the “development and strengthening of ties between the cities of the Russian Federation and foreign cities” required photographs of Moscow generally and specifically the Krasnopresnenski area be sent to Paris for an exhibition about urban development, and that photographs of Moscow be sent to Berlin, Helsinki, and Tokyo for photography exhibitions about Moscow. [23] The plan also required the Union of Journalists to send a variety of regional photography albums and journals about the “Life and Activities of Workers” to Finland, and the government requested that the Union of Journalists begin collecting photographs to send abroad, pending further instructions. [24]

Journals such as Ogonek corresponded with government agencies, unions, and international organs, but especially the photo section of the SSOD. The latter became particularly important in organizing international exhibitions inside and outside of the Soviet Union, and generally facilitating correspondence between foreign and domestic photojournalists. The SSOD was established in 1958, formerly known as the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS) founded by the Council of People’s Commissars in 1925. The official tasks of VOKS were to inform the Soviet public of foreign cultural achievements and promote Soviet culture abroad, most notably through organizing and participating in international exhibitions, competitions and festivals. [25] Despite its ties to the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs and the secret police, both societies maintained that they were voluntary associations and were officially independent of the state and Party. [26] By 1957 VOKS had established “friendship societies” with 47 countries. This number grew under the new management of the SSOD, and by 1975, VOKS maintained contacts with 7500 organizations and public figures worldwide, and held about 2000 events annually in the Soviet Union alone. [27]

In 1960, the photo section of the SSOD claimed working ties with photography organizations in East Germany (GDR), Hungary, China, Romania, the United States, Britain, France, Italy, West Germany, India, Switzerland, and Canada. [28] In the Soviet Union, its membership boasted nearly 200 of the leading photojournalists from Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Riga, Minsk, Yerevan, Almaty, Tashkent, and other Soviet cities. [29] It regularly collaborated with the photo section of the Union of Journalists as well as TASS in securing images for exhibitions in the Soviet Union and abroad. [30] It also planned numerous exhibitions of works by Soviet photographers who traveled abroad extensively (particularly those who worked for Ogonek). [31] Furthermore, the Union claimed that it successfully mediated contacts between these prominent members of the Soviet press and their foreign counterparts, not only from socialist countries, but from Canada, Italy, and Great Britain. [32]

The photo section of the SSOD itself was not a club; it lacked a laboratory and did not have an official newsletter or journal. [33] The facilitation of foreign exhibitions featuring Soviet photographers and organization of Soviet exhibitions of prominent foreign photographers was of utmost importance to the members of the photo section of the SSOD. Furthermore, membership included some of the most prominent photographers and photography editors, such as Marina Bugayeva and Dmitri Baltermants, who was the vice-president of the photo section. Shakhovskoi and Baltermants regularly received letters inviting members to participate in international exhibitions, for instance, in Milan and Barcelona. [34] They also prepared personal exhibitions of SSOD members abroad. Generally, organizers would prepare around 30 pictures for international submissions, and around 100 for personal exhibitions abroad. [35]

Shakhovskoi’s letters reveal that photographers in the Soviet Union were increasingly participating in an international community, bringing the Soviet Union into closer contact with the outside world. This itself was nothing new, but photography played an important role in this process. Photographers provided visual documentation and lent authenticity to claims about what life was like in the Soviet Union (whether or not those claims were verifiable or in fact “true”). Of course, approved photographs of the Soviet Union had been used in the foreign press and exhibitions before. What is unique is the sheer number of images changing hands, as well as the spike in Soviet photographers participating in exhibitions abroad with the permission of Soviet governing agencies. [36] The existence of a Union that facilitated these interactions at all is a testament to the altered cultural environment of Khrushchev’s thaw.

Despite not offering permanent facilities such as dark rooms or laboratories, the SSOD did provide aid and materials to photography clubs. One request for such aid came from a factory photography club in Moscow in 1963, planning an exhibition of its members’ work (though there is no specific mention of where their exhibition was to take place) the following year. In response to the request, the SSOD stated that in order to receive assistance, the club’s current plan needed to not only expand the range of subjects photographed for their exhibition, but also attempt to diversify the materials they planned to use for advertising, such as posters and brochures, as well as submit the estimated number and cost of the materials. [37] The report estimated that the cost of the exhibition would not exceed 3000 rubles, with posters costing around 4 rubles and booklets between 50 and 60 kopeks. [38]

Additionally, foreign photographers who wished to visit the Soviet Union often submitted their plans to VOKS or the SSOD. If the photographer’s plan was approved, the SSOD had the ability to expedite visa paperwork and the necessary permits and provide invaluable support should the photographer have difficulty with local authorities. Though the SSOD was ostensibly a voluntary organization that maintained it was free of government interference, its ability to provide visa support suggests that at the very least they maintained contacts with the Soviet security services. One such instance involved Swiss photographer and journalist Peter Schmidt, who was working on an illustrated book about life in the USSR. Schmidt arrived in the Soviet Union on a tourist visa in 1958. [39] In order to extend his visa, he applied to the photo section of the SSOD, along with an itemized list of shooting locations in Moscow, Tashkent, Astrakhan, Tbilisi, Baku, Sukhumi, and Irkutsk. [40] He also expressed interest in visiting Yakutsk, Birobidzhan, Riga, and Leningrad if his visa was extended, and promised to provide lists of shooting locations for those areas as well. [41] SSOD representative V. Kuzin, who was handling the request, noted that while he could assist in extending Schmidt’s visa in Moscow, the information regarding his travels outside of the capital city needed to be much more specific. [42] Furthermore, Kuzin stated, “we will be able to discuss the issue of assisting Schmidt in the field only after he agrees to travel routes with the Foreign Ministry (MVD) of the USSR.”[43] This was certainly not least due to Schmidt’s request to visit the Aleksandrov prison complex while in Irkutsk, along with other politically sensitive areas. [44] While there were limits to the help the SSOD could provide, it proved itself a useful resource for foreign photographers.

The annual reports of the photo section of the SSOD reveal the extent of its participation in and control over Soviet photographic institutions. [45] In a January 30, 1959 summary of their year-end plan in 1958, the SSOD reported that it had prepared and sent the country’s nine largest photographic exhibitions abroad from that year, which included 25 complete photo collections, 36 photo essays, as well as countless photo series and photo displays totaling 531,000 photographic prints. [46] This did not include the additional 480,000 photography prints that the SSOD sent abroad that were not part of a larger exhibition or display. [47] The estimated total number of images exchanged between the Soviet Union and foreign countries in 1959 was to increase by over 24,000 photographs, which included stock press photographs as well as photographs for international exhibitions. [48] The report concluded that the majority of the images sent to international exhibitions depicted “the life and culture of the Soviet people, and the diverse landscapes of the USSR,” reflecting Khrushchev’s reorientation of Soviet life. Furthermore, the Union report concluded that its efforts were, for the most part, successful overseas, “as evidenced by the large number of requests for Soviet photographs, as well as the number of international awards, diplomas, and medals received by members of the photo section in 1958.”[49]

The minutes of the annual General Assembly of the photo section of the SSOD further demonstrated its importance in the distribution of Soviet photography abroad. In their annual review meeting of 1959 and in discussing the projected plan for 1960, approximately 100 delegates from various illustrated journals presented and discussed a variety of issues, ranging from general topics to detailed minutia. Delegate V. Kuniaev asked the assembly to consider organizing an international photo exhibition in Moscow. [50] Representative B. Kudoiarov gave a speech about the importance of quality paper for photographic prints. [51] A. Shternberg “[found] it necessary to conduct a careful selection of obsolete and technically unsatisfactory photographic work…” and declared that it was essential “to replenish the storeroom section of works from the exhibition The Seven-Year Plan in Action” so that prints would be immediately available if requested by domestic or foreign press outlets. [52] L. Grigoriev suggested that the SSOD needed to put forth more effort in announcing foreign exhibitions in both capitalist and socialist countries, because so few Soviet newspapers covered these shows. Others agreed, and suggested compiling a directory of the Soviet works most often shown abroad so that newspapers and journals could reprint these images domestically without issue. [53]

Interestingly, one of the final speakers at the assembly, A. Smolianov, noted that the success of Soviet photography internationally depended very much on the tastes of the foreign audience. This meant that the photo section needed to expand its print stores. Both the Union of Journalists and the SSOD had multiple printed copies of famous and frequently requested images in storage at their office. These images were available by request for smaller photography exhibitions (particularly for workers clubs) in the Soviet Union and abroad. Somalianov insisted that these stores needed to incorporate younger, more experimental photographers.

We need to update our work, to bring into the photo section all the best pictures… It is necessary to actively involve young people in the work of the Union. This idea is not popular in the office section. This is wrong and creates difficulties in meetings with foreign delegations. In this regard, the bureau must vow to actively engage young amateur photographers. [54]

Smolianov, while admitting that the work of photography masters received positive feedback from critics abroad, noted that this work was not enough to sustain interest in Soviet photography. The SSOD needed to have readily available samples of the work of young artists, particularly amateur photographers. Other members, specifically Georgii Petrusov and Valerii Gende-Rote, supported Smolianov’s suggestion.

It was not only the SSOD that noticed the importance of updating the photographs approved for consumption abroad. A year earlier, on July 22, 1958 the Union of Journalists, in collaboration with the photo section of the SSOD, sent a delegation of journalists, editors, and photographers to Argentina to meet with Latin American journalists. Representatives at the meeting included Ogonek editor Sofronov, and the editor of Izvestiia, Aleksei Adzhubei. In his reports to the Ministry of Culture, Union and Journalists and the SSOD, Adzhubei stated that his “trip to Latin America spoke volumes.”[55] The quality of photographs that Moscow had sent to delegates from Uruguay for an upcoming exhibition of Soviet photography shocked Adzhubei. In a conversation between himself and another representative, Adzhubei voiced his displeasure.

He saw the exhibition and the photographs of Moscow were quite outdated. Some of them, in his opinion, were very low quality photos, for example, depicting the streets of Moscow, some of which made them seem deserted. Photographs of Moscow transport were very unsightly. Tram stops showed public overcrowding. Comrade Adzhubei believed that the organizations that provide photographs to Latin America should be more rational, and select photos that illustrate the life of the Soviet people. [56]

Adzhubei’s concerns were twofold. Not only were the photographs outdated, but the approved photographs were also unseemly because they were not particularly flattering. The Soviet Union needed standards, according to Adzhubei, for press and exhibition photographs, whether the images were displayed and printed domestically or in foreign countries. This was the main responsibility of the SSOD which, according to the editor, needed to be more discerning.

In an effort to rectify this problem, the photo section of the SSOD began sending letters to each of its members, inviting them to participate in international exhibitions and encouraging them to pass exhibition information on to colleagues and amateurs. What is curious about these calls for submissions is that they were not only for press photography competitions, but art photography exhibitions as well. From September 1959 to January 1960, the photo section notified its members of 10 competitions, held in both socialist and capitalist countries. [57]

Loosened restrictions on incoming and outgoing photographs and increased interest by the foreign public in life behind the Iron Curtain meant that the government was selling nearly twice as many negatives to foreign press outlets in 1960 as it had been in the previous decade, and that number was steadily increasing. Only five years earlier, the number of images sent abroad increased from 1,511,670 photographs in 1955 to 1,522,500 in 1960, and 1,524,000 in 1965. [58] Those these numbers appear to be evidence of stagnation, they are in fact indicative of how a medium largely ignored by the Soviet government in terms of funding, was in fact expanding. Though the average price of a negative print had fallen from 48 rubles in 1955 to around 45 rubles in 1956, the sheer number of negatives sold by the Soviet government to the foreign press totaled well over 1 million rubles in revenue for Soviet publishing houses in 1960. [59] This excluded actual photo prints, as well as additional fees that Soviet press outlets charged for including descriptions (with translations) of the photographs for newsprint, which amounted to another quarter of a million rubles in 1960. [60] Of course, organizations such as the SSOD preferred to send photographic prints over negatives to prevent foreign agencies from making endless copies of Soviet press photographs. [61]

Despite the propaganda or monetary value of photography to the state and Party, photographers and members of the photo section of the SSOD admitted that the new era demanded a new type of photograph. In her address to the General Assembly of the Union of Soviet Societies on February 10, 1960, Bugayeva stressed the primacy of reorienting photography to fit the new milieu.

Now the task before the masters of art photography is to improve not only the quality but also the ideological level of their work especially that which relates to master’s work in foreign countries. We have to think about the full implications of the subjects of our works. The audience, including foreigners, is tired of the standard production of images where the foreground is not people, but machines. Now more attention should be given to portraits, genre and reportage shots… we have not developed the theme of the Party’s guiding force in our society enough, and we do not shoot such hot topics as friendship of the peoples, the struggle for peace, the life of the working or collective farm family, and advances in science. [62]

As Chairman Shakhovskoi of the SSOD had pointed out the previous year, the most effective means of propagating Soviet success was not through images of heavy industry, but shots of the life of Soviet families, and more importantly, Soviet presence (and influence) outside of the Soviet Union. Photographs in Ogonek demonstrate that photographers were not only looking inwards and evaluating the lives of Soviet peoples, but were increasingly looking outwards as well, towards the West and developing nations of Asia and Africa.

Amerika and USSR: Official Exchanges of Photos between Governments

Of course, the decision to encourage more photography exchanges had its own propaganda value. It corresponded with the opening of borders to Western influences, a trend that the government had dabbled with since the mid-1950s. In 1956, the State Department of the United States and the Central Committee agreed to exchange illustrated journals, and Amerika and USSR were founded by their respective government foreign departments. These journals were created expressly for the purpose of acquainting the Soviet public with American culture, and vice versa. Though the first print runs were small, the Central Committee recognized the potential of illustrated journals for tapping into foreign interest in the Soviet Union. [63]

Although the Central Committee was extremely suspicious of the content of journals like Amerika, the government was under no obligation to satisfy the curiosity of its people or the outside world. Despite the effort required to counter Soviet citizens’ intense interest in the journal Amerika, the government did not suppress the journal itself, though it was available in limited quantities. While some issues of the journal were available at Soiuzpechat kiosks, particularly those nearest government offices where they would fall into the hands of “reliable” Party officials as opposed to the average citizen, most were sold to journal editors and government administrators. [64] Many of the allotted journal subscriptions to foreign illustrated journals ended up in the hands of newspaper, magazine, and publishing staff. Thus, the decision to provide outside examples of press photography directly to the editorial staff meant that photojournalists, more than the average Soviet citizen, had even more access to examples of foreign photography.

Despite the Central Committee’s cautious approaches to cultural exchanges the number of illustrated journal exchanges between the Soviet Union and other countries grew rapidly. Only a year after the Central Committee approved the Amerika and USSR negotiations, the Soviet Union sponsored exchange programs with 22 countries. [65] Exchange programs included countless journals, magazines, newspapers, and newsletters. These publications printed an average of “2000 images a month, of which about 75 are color images,” the majority of which were published in “bourgeois” countries. [66] The exponential expansion of illustrated journals about the Soviet Union was welcomed by Soviet photojournalists, who were encouraged to travel to various foreign locations and were commissioned to provide editors with an average 50-60 publishable prints per month. [67]

Conclusions

In the late Soviet period, beginning with Khrushchev’s cultural thaw, photographers began to focus less on massive industrial projects and more on the private lives of Soviet citizens. This can be seen in illustrated journals such as Ogonek, which devoted itself to special interest stories about individuals and their everyday lives. The magazine coupled pictures of average citizen’s intimate lives with illustrated stories about exotic foreign locales, bringing Soviet people closer to an outside world that they otherwise would have very little contact with. Ogonek photo essays focused on local customs and cultural heritage, not necessarily urban industrial environments. Cultural exchange programs between Western Europe and the Americas furthered this process. Increasing contact between Soviet and foreign photographers was facilitated by the SSOD and various other photography sections. Put together, these developments in photography meant that photojournalists were exposed to the work of photographers outside the Soviet Union and participated in numerous domestic and international exhibitions. For the first time in decades, photojournalists were not only explaining what it meant to be a Soviet person, but how that personhood was constructed and influenced by contact with the outside world. Ogonek editor Anatolii Sofronov and head of the photo section of the SSOD Vladimir Shakhovskoi encouraged these developments. Ultimately, beginning in the late 1950s, the illustrated journal Ogonek and the photo section of the SSOD took an active role in introducing Soviet readers and viewers to life outside of the Soviet Union, while cultural exchanges and the journal Amerika simultaneously contributed to their identity as Soviet citizens.

Works Cited

GARF f. 9518r, op. 1, d. 10, l. 58.

GARF f. 9518r, op. 1, d. 18, ll. 136-138.

GARF f. 9518r, оp. 1, d. 46, l. 25.

GARF f. 9518r, op. 1, d. 68, l. 4.

GARF f. 9518r, op. 1, d. 75, l1. 92-93.

GARF f. 9518r, op. 1, d. 651, l. 109.

GARF f. 9518 r, op. 1, d. 652, l. 58.

GARF f. 9518r, op. 1, d. 653, ll. 6-18, 22.

GARF f. 9518r, op. 3, d. 39, ll. 15, 152.

GARF f. 9576 r, op. 16, d. 46, ll. 36-37, 88,168-9.

GARF f. 9576r, op. 16, d. 47, ll. 178, 233, 250, 256.

GARF f. 9576r, op. 16, d. 86, l1. 37, 38.

GARF f. 9576r, op. 16, d. 86, l. 88.

RGANI f. 11, op. 1, d. 49, l. 5.

RGANI f. 11, op. 1, d. 20, ll. 2-4.

RGANI f. 89, op. 46, d. 11, l. 3.

Clark, Katerina. The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

David-Fox, Michael. “From Illusory ‘Society’ to Intellectual ‘Public’: VOKS, International Travel and Party-Intelligentsia Relations in the Interwar Period.” Contemporary European History 11, no. 1 (2002): 7-32.

“Den’ za dnem.” Ogonek no. 8 (1959): 8.

Drachinskii, Nikolai. “Kuznets mira.” Ogonek, no. 10 (1960): 2-5.

Il’inskii, B. “Iz zapisok kollektora.” Ogonek, no. 47 (November 1961): 22-3.

Ogonek, no. 47 (1958): 33.

Solodar’, Ts. “Dvesti Molodozhenov.” Ogonek, no. 5 (1958): 2-4.

Footnotes