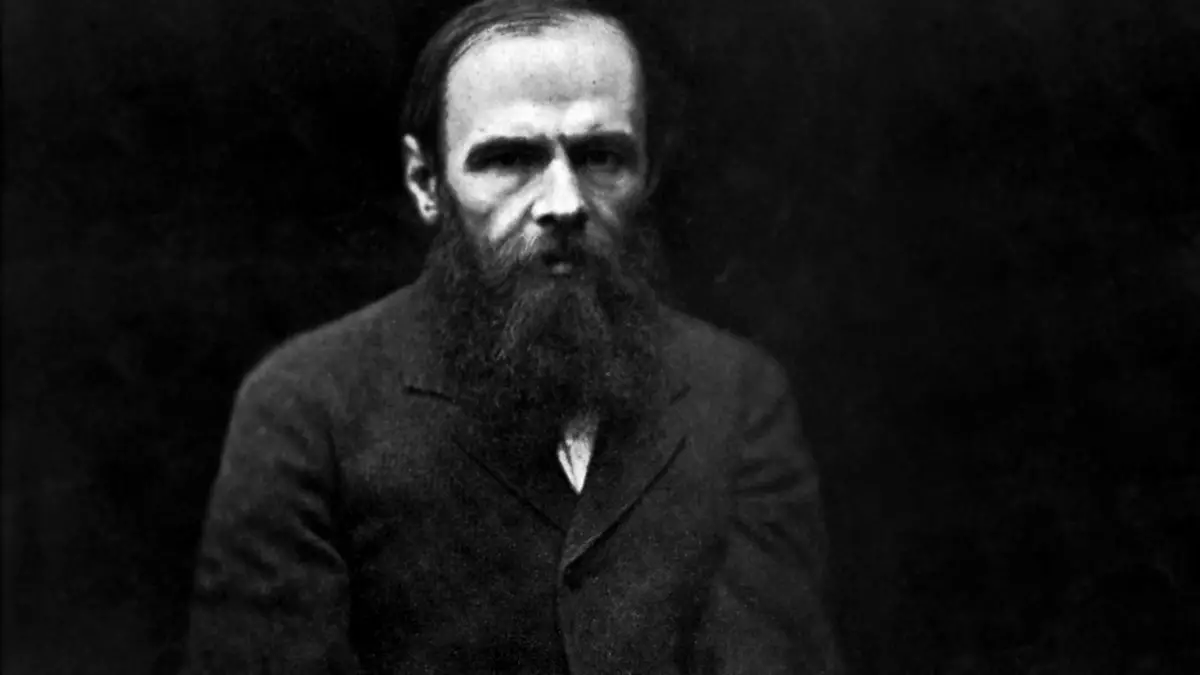

Nietzsche once described Dostoevsky as “the only person who has ever taught me anything about psychology” (Gide 168). Upon looking deeper into the connection between the two men, it is apparent that both Nietzsche and Dostoevsky had complex philosophies, and it would be difficult, if not impossible, to compare their philosophical systems completely. Therefore, focusing on a specific issue like redemption will be more productive. Redemption is a topic directly connected to larger issues of considerable importance for both Nietzsche and Dostoevsky: morality, guilt, fear, and God. By examining the views of Dostoevsky and Nietzsche on these issues in relation to redemption, we will be better able to understand how Dostoevsky influenced Nietzsche’s philosophy.

One of Dostoevsky’s clearest examples of redemption can be found in Crime and Punishment, a novel that examines the potential for evil in society and the self. Dostoevsky creates Raskolnikov, the protagonist of the novel, as the key player in his study of evil, and evil is depicted in this character as deriving directly from selfishness and cold rationality. Specifically, Raskolnikov’s rationality leads him to believe that morality is a purely subjective matter and based largely on each individual’s perspective: if “one needs, for the sake of his idea, to step even over a dead body, over blood, then within himself, in his conscience, he can, in my opinion, allow himself to step over blood” (Dostoevsky 261); this line of thinking liberates Raskolnikov to ignore societal rules and replace them with self-serving rules of his own.

Raskolnikov’s stated view mirrors Nietzsche’s description, expressed in the Genealogy of Morality, of the master’s position regarding the difference between good and evil. Nietzsche writes:

…the judgment ‘good’ does not emanate from those to whom goodness is shown! Instead it has been ‘the good’ themselves, meaning the noble, the mighty, the high-placed and the high-minded, who saw and judged themselves and their actions as good, I mean first-rate, in contrast to everything lowly, low-minded, common and plebeian (Nietzsche GM I 2).

Nietzsche explicitly divides the world into the powerful and the not, and this too parallels Raskolnikov’s thinking. Raskolnikov’s published theory on crime divides the world in a similar fashion, distinguishing people who are ordinary from those who are extraordinary. For Raskolnikov, people are divided

according to the law of nature, into two categories: a lower or, so to speak, material category (the ordinary), serving solely for the reproduction of their own kind; and people proper—that is, those who have the gift or talent of speaking a new word in their environment (Dostoevsky 260).

Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov emphasizes the importance of this distinction by sarcastically describing what happens when people overstep their bounds; when an ordinary person believes he belongs in the other category and acts outside of the bounds of the law. As a result, they will

whip themselves, because they’re so well behaved; some perform this service for each other, and some do it with their own hands…all the while imposing various public penances on themselves—the result is beautiful and edifying (Dostoevsky 262).

Raskolnikov does not recognize that he simultaneously defines good and evil and warns of the punishment for those overstepping the boundaries of their category. It is clear that Raskolnikov is not a member of the ruling class that, in Nietzsche’s view, is empowered to “say ‘this is so and so,’ they set their seal on everything” (Nietzsche GM I 2). Dostoevsky has thus created a character who believes he is in what Nietzsche would call the master’s category, but is in fact in the slave’s category: he is poor, lives in horrible conditions and has no political or social status. As a result, he is surely unable to alter the societal standards for justice and, in this way, is quite unlike the category that Nietzsche describes as the master’s.

For Nietzsche, slaves are the individuals for whom “ressentiment itself turns creative and gives birth to values: the resentment of those beings who, being denied the proper response of action, compensate for it only with imaginary revenge” (Nietzsche GM I 10). In Nietzsche’s view, the slave’s imaginary revenge takes place when the slave lacks the strength to act, but cleverness leads to a new valuation of not acting. In this way, Nietzsche proposes, slaves can credit themselves for “choosing” not to respond to their powerlessness, rather than faulting themselves for not having the capacity to respond (Nietzsche GM I 10).

Raskolnikov does create a principle of agency for himself and in that regard can be seen as resembling Nietzsche’s conception of a slave. However, Nietzsche focuses his sense of agency on deliberate inactivity, and, in that regard, envisions a slave different from Raskolnikov. In particular, Nietzsche writes that “popular morality separates strength from the manifestations of strength, as though there were an indifferent substratum behind the strong person which had the freedom to manifest strength or not” (Nietzsche GM I 13). This principle is possible only because the slave (unlike Raskolnikov) does not then act on that agency, but, importantly, the principle gives the slave a justification for not acting (that is, he had the power to and chose not to.) Raskolnikov, in contrast, believes he has agency to act, can redefine morality, and then actually follows through by murdering an old woman.

Raskolnikov’s choice has consequences, however, as he made the mistake of pursuing that which the slave cannot get away with: action. The consequence for Raskolnikov is guilt, and this consequence actually restores the alignment between Raskolnikov’s character and Nietzsche’s view. Nietzsche argues that guilt is built into humankind, as humans have developed the capacities to make promises and also memory, both for their promises and for their own actions. Nietzsche then links memory to pain, writing, “How do you impress something upon this partly dull, partly idiotic, inattentive mind…A thing must be burnt in so that it stays in the memory: only something which continues to hurt stays in the memory” (Nietzsche GM II 3). Ironically, therefore, it seems that memory is crucial for guilt (how could one feel guilty about things one has forgotten?), but guilt may simultaneously be crucial for memory (because it is the hurt that produces long-lasting recollection).

Raskolnikov’s suffering after his crime is just what one might expect in Nietzsche’s view. He is plagued with panic attacks and fever after murdering the old woman. He mistakenly believes he has the power to affect societal morality, like the master, imposing his personal valuation of “what is right.” Because of this mistake, he acts, when, in Nietzsche’s view, a slave should choose inaction, and he pays the price for his action: the punishment of guilt.

Even when the detective Porfiry takes pity on Raskolnikov and offers him an ultimatum to confess and live in prison or be convicted and hanged, Raskolnikov still considers himself an extraordinary man. There are two plausible reasons why Raskolnikov chooses life in prison rather than death: first, he continues to believe his actions were not punishable, and so refuses the stronger punishment. Second, he may have some fear of dying, and, by denying the wrongfulness of his actions, he tries to convince himself that he has nothing to fear.

The first half of the epilogue strengthens the notion that Raskolnikov confessed out of selfishness as opposed to some sort of repentance; in prison, he still does not understand that he lacks the power to re-define morality:

What does the word ‘evildoing’ mean? My conscience is clear. Of course, a criminal act was committed; of course, the letter of the law was broken and blood was shed; well, then, have my head for the letter of the law…and enough! Of course, in that case even many benefactors of mankind, who did not inherit power but seized it for themselves, ought to have been executed at their very first steps. But those men endured their steps, and therefore they were right (Dostoevsky 544).

He is unwilling to shift from his view that he is extraordinary and thus should elude the harshest punishment (death), no matter how horrid the circumstances of the crime. However, these words, coming from Raskolnikov, would be inadequate for Nietzsche, because for Nietzsche the truly great men would not have to endure—instead, their actions would never have been illegal or immoral because of the fact that they were great.

Even so, Nietzsche helps us to explain Raskolnikov’s perspective, because of Nietzsche’s emphasis on the role of illusion. Specifically, in Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche writes:

However much value we may ascribe to truth, truthfulness, or altruism, it may be that we need to attribute a higher and more fundamental value to appearance, to the will to illusion, to egoism and desire. It could even be possible that the value of those good and honoured things consists precisely in the fact that in an insidious way they are related to those bad, seemingly opposite things, linked, knit together, even identical perhaps. (Nietzsche BGE I 2).

Raskolnikov’s rigidity in his view that he is a master is due to the fact that he does not recognize this “will to illusion”; his rigid logic is not conducive to the “perhaps” nature of Nietzsche’s perspectivism. Raskolnikov’s twisted rationality can therefore be understood, in Nietzsche’s framework, as illusion.

It is also possible that Raskolnikov’s choice to live in prison is related to fear, another issue tied to redemption for both Dostoevsky and Nietzsche. Raskolnikov has been a fearful character throughout the novel, but his fear is especially visible when a view of death is described to him by another character, Svidrigailov. Raskolnikov claims, “I do not believe in a future life” (Dostoevsky 289), but Svidrigailov describes death as “one little room there, something like a village bathhouse, covered with soot, with spiders in all the corners, and that’s the whole of eternity.” In response, we see a burst of fear from Raskolnikov: “‘But surely, surely you can imagine something more just and comforting than that!’ Raskolnikov cried out with painful feeling” (Dostoevsky 289).

Raskolnikov does not reject altogether Svidrigailov’s claim that there is an afterlife; instead, he hopes for a more “comforting” vision. This is in contrast to Nietzsche’s proposal—with no afterlife at all. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, when the tight-rope walker falls and describes his fear of the devil, Zarathustra comforts him by saying,

‘On my honour, friend,’ answered Zarathustra, ‘all you have spoken of does not exist: there is no Devil and no Hell. Your soul will be dead even before your body: therefore fear nothing any more!’ The man looked up mistrustfully. ‘If you are speaking the truth,’ he said then, ‘I leave nothing when I leave life. I am not much more than an animal which has been taught to dance by blows and starvation.’ (Nietzsche Zarathustra Prologue 6)

Of course, Raskolnikov lacks Zarathustra’s guidance, and thus, left with Svidrigailov’s grim view of the afterlife, Raskolnikov sees life in prison as the better of two dark options. This seems to imply that “no future life” after death is, for Raskolnikov, a fearful option, and, if so, then we must consider the role and influence of his fear. It seems plausible that it also might be a contributor to his amorality: if he can convince himself that there is no moral code, then there would be no such thing as violations and hence no consequences to be paid, once life is over. If so, the fearful threat of hell is removed.

But there may, in addition, be a third factor in play, because it is possible that Raskolnikov’s confession, leading to his life in prison, links back to Nietzsche’s view on guilt. Nietzsche writes that:

Throughout most of human history, punishment has not been meted out because the miscreant was held responsible for the act…but rather it was out of anger over some wrong which had been suffered, directed at the perpetrator…anger held in check and modified by the idea that every injury has its equivalent which can be paid in compensation, if only through the pain of the person through injuries. (Nietzsche GM II 4)

This logic – a retributive view of punishment – could be applied to Raskolnikov’s case, but perhaps with a peculiar twist. Raskolnikov understands, following a logic similar to Nietzsche’s, that he is eligible for punishment, but he is guided by another aspect of Nietzsche’s claim:

Instead of an advantage directly making up for the wrong (so, instead of compensation in money, land or possessions of any kind), a sort of pleasure is given to the creditor as repayment and compensation, — the pleasure of having the right to exercise power over the powerless without a thought, the pleasure of doing evil for the pleasure of doing it. (Nietzsche GM II 5)

By taking control of his own fate and choosing his punishment, Raskolnikov tries once again to take on the role of the master—a role that he is not entitled to, as we have discussed. Here, too, his logic is similar to Nietzsche’s, because, as Nietzsche writes, “Through punishment of the debtor, the creditor takes part in the rights of the masters: at least he, too, shares the elevated feeling of despising and maltreating someone as an ‘inferior’” (Nietzsche GM II 5).

Overall, then, it is clear how Dostoevsky’s novel impacted Nietzsche’s philosophy; indeed, one can read the novel as a lengthy parable describing how things will go terribly wrong if a slave presumes to take steps, or make judgments, that should be reserved for a master. However, there is also a sudden and jarring twist in the epilogue of Crime and Punishment which does not seem to fit with the rest of the book. Specifically, Raskolnikov is suddenly redeemed after years of reading the Bible in prison. He embraces Sofia, a former prostitute who is intensely spiritual and has chosen to follow Raskolnikov to prison:

They wanted to speak, but could not; tears stood in their eyes. They were both pale and thin; but those sick pale faces were bright with the dawn of a new future, of a full resurrection into a new life. They were renewed by love; the heart of each held infinite sources of life for the heart of the other (Dostoevsky Epilogue).

This emphasis on resurrection and a new future fits with a Christian view of redemption, in which one is somehow neutralizing the past, both in terms of one’s personal sins (murdering the old woman and her sister) and the ancestral sin of man (murdering Christ). This emphasis does not, however, fit with Nietzsche’s claims which, as we have seen, explicitly reject the notion of an afterlife, and, with that, presumably reject the notion of heavenly redemption. Dostoevsky desperately tries to reconcile his previous conclusion of guilt and equilibrium through punishment (a conclusion which Nietzsche accepts), with the negation of the past through salvation in the afterlife (a view Nietzsche rejects). However, this reconciliation, and, indeed, the redemption itself, feels forced and unconvincing. Raskolnikov’s redemption is described in only two pages, and the novel ends abruptly with a short passage:

But here begins a new account, the account of a man’s gradual renewal, the account of his gradual regeneration, his gradual transition from one world to another, his acquaintance with a new, hitherto completely unknown reality. It might make the subject of a new story—but our present story is ended (Dostoevsky Epilogue).

It is easy to imagine that Nietzsche would have preferred a different epilogue to Dostoevsky’s novel, because he holds a very different view than redemption achieved through Christian belief. In fact, Nietzsche argues that:

It is false to the point of absurdity to see in a ‘belief’, perchance the belief in redemption through Christ, the distinguishing characteristic of the Christian: only Christian practice, a life such as he who died on the Cross lived, is Christian…In fact there have been no Christians at all (Nietzsche AC 39).

Nietzsche is thus arguing that negation through redemption does not achieve balance, and, moreover, that no one has actually lived to the standard of Christian ideals. And even if one allows the possibility of living to these standards, it seems plain that a murderer such as Raskolnikov would not meet this criterion.

Nonetheless, Nietzsche does describe a type of redemption, but one that is very different from the Christian view. In Zarathustra, Zarathustra says to his followers,

To redeem the past and to transform every ‘It was’ into an ‘I wanted it thus!’ – that alone do I call redemption! Will—that is what the liberator and bringer of joy is called: thus I have taught you, my friends! But now learn this as well: The will itself is still a prisoner. Willing liberates: but what is it that fastens in fetters even the liberator? ‘It was’: that is what the will’s teeth-gnashing and most lonely affliction is called. (Nietzsche Zarathustra II Of Redemption).

Nietzsche’s view is similar to the Christian view on the specific point that, in both perspectives, actions in the past are unchangeable, and this creates suffering: “Powerless against that which has been done, the will is an angry spectator of all things past. The will cannot will backwards; that it cannot break time and time’s desire” (Ibid). But instead of striving for the negation of the past—in essence an erasure created by forgiveness—Nietzsche argues that redemption can be achieved by affirming the passage of time, when the “creative will says to it: ‘But I willed it thus!’ Until the creative will says to it: ‘But I will it thus! Thus shall I will it!’” (Ibid).

Once again, Nietzsche’s emphasis is on agency, and on the idea that, by taking credit for past actions (“I willed it thus”), one “redeems” past actions. Nietzsche therefore presents an entirely coherent view, which sounds much more similar to Raskolnikov’s view before the epilogue. Nietzsche has already affirmed the possibility of a master imposing his will in the sense of asserting what is wrong and right; he has also allowed the possibility of a slave offering a limited version of rebellion, by asserting that inactivity was deliberate, and, with this, asserting counter-factually that action would have been possible. It is a small step from these steps of subjectivism to the step Nietzsche proposes for redemption – of re-writing the past and asserting that prior actions were, in fact, deliberate and “willed.” One cannot, Nietzsche agrees, change the past, but one can apparently change how the past is understood and recalled. Nietzsche is also affirming the passage of time and the fact that actions will become irreversible.

Dostoevsky is not able to take this final step that Nietzsche is able to take, perhaps due to his desperate hope that the Christian view of redemption could somehow cohere with the rest of his philosophy. As a result, Dostoevsky clings to the optimistic prospect of Christian redemption—but at the price of ending up with a view that is internally contradictory; Nietzsche rejects this final aspect of Dostoevsky’s view.

Works Cited

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, translation: Richard Pevear, Larissa Volokhonsky, and Tina Frolund. Crime and Punishment. Libraries Unltd Inc, 2007.

Gide, André. Dostoevsky. Telegraph Books, 1981.

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Keith Ansell-Pearson, and Duncan Large. The Nietzsche reader. Wiley-Blackwell, 2006.

You Might Also Like

(includes current article)

The Dostoevsky Memorial Apartment Museum in St. Petersburg

The Dostoevsky Memorial Apartment Museum at 5/2 Kuzneckny Pereulok in St. Petersburg is dedicated to drawing a picture of the great Russian writer as a person with a focus on his work habits, on his concerns, and particularly on his family life. Even discussion of his greatest novels is presented within the context of telling […]

Crime and Publishing: How Dostoevskii Changed the British Murder

A few words on this book: Described by the sixteenth-century English poet George Turbervile as “a people passing rude, to vices vile inclin’d,” the Russians waited some three centuries before their subsequent cultural achievements—in music, art and particularly literature—achieved widespread recognition in Britain. The essays in this stimulating collection attest to the scope and variety […]

The Hero of Cana: Alyosha’s Ode to Joy in The Brothers Karamazov

Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov opens with a particularly unsatisfying note. The fictional narrator declares in his “From the Author” that the hero of the book is Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov. Quickly following this declaration is a confession: “To me he is noteworthy, but I decidedly doubt that I shall succeed in proving it to the reader” (Dostoevsky 3). […]

Suicide as a Final Reconciliation of Conflicting Identities in The Brothers Karamazov

The function of violent death is complex in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: it serves as the driving focus of the work, calls into question the many characters’ agency and morality, and provides a forceful resolution. At the forefront of the novel is the murder of Fyodor Pavlovich by one of his sons. Parricide is the […]

Rational Perversions of Love in The Brothers Karamazov: Spiritually Fruitless, yet Thematically Useful

In The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky spends countless pages elucidating his ideal of love. Among his many characters, he offers complex portraits of two intriguing individuals, whose love does not quite fit his definition of this ideal. The Grand Inquisitor and, by extension, his creator Ivan, are often seen as simply hyper-rational characters who reject God’s […]

Or, find all Dostoevsky articles on this site.