Children’s literature of the Soviet Union never failed to mirror the volatile political climate of the Soviet state. Between the end of the civil war (1917-1922) and the rise of Stalinism (1929-1953), the Soviet leadership introduced various pedagogical innovations for educating and socializing a generation of socialist youth. As the leadership had no previous experience in systematic educational development, early Soviet pedagogy was experimental and exploratory. Children’s literature from the early Soviet era (the 1920s and 30s) closely reflected this phenomenon. This paper will demonstrate that these writings mirror the confusion generated by early Soviet pedagogy and paralleled the experimental nature and immaturity of the Soviet educational system. Although these authors pressed forward state expectations for their young readers, effectively creating Soviet propaganda, they unintentionally revealed the ineffectiveness of Soviet pedagogy.

The Soviet leadership wished to design an effective set of pedagogical materials that would achieve their expectations. They hoped that citizens would embrace Bolshevik ideals and acquire the technical skills needed to become obedient laborers for socialization and modernization. [1] Lenin’s goal of nurturing a generation of faithful workers with “labor discipline (трудовая дисциплина)” [2] is evident in his speeches from 1919-1921. [3] He believed the task for the working people was to build a Red Army of Labor “cemented by labor discipline.”[4] For Soviet policymakers, teachers, and propagandist writers, educational effectiveness meant adopting a pedagogical curriculum and style to achieve this aim. However, despite their essentially authoritarian educational goal of fostering obedience and loyalty to the state, the Soviets actually implemented an educational plan aimed at catering to the individual.

Although the children’s literature explored in this paper did genuinely promote socialist ideology, it often overplayed Soviet fantasy, thus undermining the implementation of state goals. In many cases, early Soviet education advocated for freedom that fundamentally countered Soviet expectations for children to follow directions from the regime without questioning or interpreting them.[5] In the immediate post-civil war Soviet Union, the experimental adoption of these methods in pursuit of flexibility, freedom, and encouraging fantasy yielded chaos and confusion when coupled with the Union’s decidedly anti-freedom educational goals.

Russian and then Soviet primary education had only begun to develop in the 1920s. With no extensive history or experience, Soviet education became a big pedagogical laboratory, in which Soviet education planners carried out extravagant experiments. The radical activist Scott Nearing emphasizes its scale, suggesting that course content, instructional methodology, and pupils’ social organization were all affected by this experiment.[6]

Nikolai Ognyov’s novel, The Diary of a Communist Schoolboy (1928), offers a detailed account of the impact of early Soviet education on its pupils through the eyes of schoolboy Nikolai Rybazev. Ognyov shows the educational system in a negative light by portraying Nikolai’s daily school life as confusing chaos. However, while Ognyov challenges the pedagogical paradigm, he expresses clear approval and promotion of Soviet ideals.

For example, Ognyov describes Nikolai and his classmates before a class discussion as passionately celebrating Lenin’s slogan, “Let us learn, learn, and learn!”[7] He also acclaims the application of Soviet ideology in personal life through Nikolai, who holds the firm belief that one’s responsibility is to be useful to society and to strive for universal Communism:

We live and study in order to create a powerful and civilized country and to help our neighbors. We must remember that the sea is made of little drops, and every man is a little drop […] But if one drop is idle, it interferes with the sea; then there is no room for it in the sea, and it must be got rid of. Therefore, let us acquire knowledge and protect Soviet Russia against the damned bourgeoisie.[8]

Despite his determination, Nikolai later recounts that the introduction of the Dalton Plan[9] into Soviet education resulted in confusion among Soviet pupils. The Dalton Plan was developed by an American progressive, Helen Parkhurst, and was named for Dalton, Massachusetts, where it had been first implemented. Lenin’s wife promoted this pedagogy and personally translated Parkhurst’s book, The Dalton Laboratory Plan, into Russian.[10] The Plan attempted to tailor curricula to each student’s needs, interests, and abilities and, in doing so, enhance the student’s social skills and sense of responsibility.[11] Although many schools today, including in Russia, successfully use teaching models based on the Dalton Plan, in Nikolai’s view this model turns the classroom into a place that is “fearfully noisy and rowdy.”[12] Teachers who attempt to calm students with discipline are accused by the students of nostalgia for the old, tsarist-era school.[13]

The structural foundation of a Dalton education includes an assignment and a practicum (lab).[14] Parkhurst designed the lab component to allow more flexibility and independence in students’ exploration of course content. But to Nikolai and his classmates, lab assignments only make students feel burdened as if the Dalton Plan “hangs round” their neck “like a bag of corn;”[15] they are constantly reminded of tasks that they do not have time to do. As the students revolt against the Dalton Plan, Nikolai questions the meaning of the labs and the so-called “self-government” promoted by Dalton.[16] He feels the system lets teachers do nothing, and the pupils have to find everything out for themselves.[17] Confusion also prevails among faculty members, whose discussion of the Plan is continual, but never progresses throughout the school year.[18]

While Soviet leaders wanted young students to become useful, obedient citizens, the Dalton Plan, as portrayed in this piece of children’s literature, seems to have moved students further away from this goal. The Plan was incompatible with the communist state and its goals.

The Dalton Plan was championed by Soviet leaders, however. Lenin in a Soviet decree advocated for education freedom, aiming at ridding the predominant influence of the Orthodox Church over the educational system.[19] Once religion and education were separated, Soviet leaders realized that they needed a new educational system and philosophy. Although it would be ideologically wrong to accept them all, Western concepts of liberty and freedom were appealing.[20] They apparently contrasted with tsarism and religious dogma and thus could help clearly define the new government as separate from the old.

However, freedom in education, as seen in the Western model, although seemingly advocating for the same liberty as Lenin’s education decree, was in fact a very different concept.[21] The Soviet’s pursuit of freedom for education was relative to religious domination;[22] it was never founded on love of truth and freedom of thinking as in the West. In fact, hard-line Soviet educational mandates had been essentially as authoritarian as the Orthodox rule that the Soviet leadership sought to set itself apart from.[23] The stability of Soviet regime depended on successful control of citizens’ mentality, not encouragement of critical thinking.

While The Diary deliberately reveals the experimental failures of early Soviet pedagogy, Innokenty Zhukov’s Voyage of the Red Star Pioneer Troop to Wonderland (1924) unintentionally parallels the experimental nature of early Soviet pedagogy by exposing its own ineffectiveness in implementing the state’s ultimate goals through pedagogy. Despite Zhukov’s effort to promote the Soviet agenda, Zhukov’s writing style and story-telling model distance his young readers from Soviet expectations.

Zhukov promotes the Soviet mandate and the regime’s expectations for children in the context of a political utopia presented in a science fiction story. The Young Leninist Pioneers from 1924 travel through time to 1957, where they find a physically-fit population, a high-tech society, and a worldwide commune of universal brotherhood.[24] The Leninist Pioneers of 1957 are adept in all sorts of swimming styles, and their skin shines when they dive into the water.[25] The 1924 Soviet Pioneers also see that, by 1957, air travel has become as prevalent a method of transportation as bikes and horses.[26] Zhukov specifically points out that airplanes are rare in 1924,[27] pushing his young readers to see it as their responsibility to achieve this future technological advancement. The most striking observation for the boys is that the entire world has turned into a “single labor commune,”[28] and the youngsters from 1924 are encouraged to reach out and see that a statue of Lenin is erected in every city of the world.[29]

Unfortunately, the bright communist future proves itself to be unapproachable due to Zhukov’s overemphasis on and over-dramatization of the amazement of the children from 1924. While awestruck by the achievements of 1957, they cannot take a role beyond that of observer. They are constantly “amazed,” [30] “enraptured,”[31] “riveted”[32] and “convinced […] of their new friends’ superiority.”[33] Zhukov repeatedly uses the expression “with their eyes wide open”[34]to describe how the children observe the future world. Highlighting the boys’ emotions to show their keen interest and thus inspire the same awe in young readers could have been an effective pedagogical tool to attract readers’ attention, encourage them to empathize with the characters, and see their goals and ambitions as their own. However, the more such amazement is stressed at the expense of practical advice and work to achieve those goals and ambitions, the more the children are shown to be simply unable to take initiative.

Zhukov’s account continually stresses that “our boys didn’t know that”[35] and “our boys still hadn’t seen and learned all this,”[36] contrasting the heroes from 1924 with their more advanced counterparts. He stresses the heroes’ ignorance to show that there is room for progress and to encourage a sense of urgency for learning, but the constant emphasis on such ignorance seems to suggest the heroes’ fundamental intellectual inferiority. The 1924 boys are overwhelmed by the 1957 House of Young Leninist Pioneers; they cannot keep up with and even “had no time to listen”[37] to the world news transmitted through the radiophone receiver. Both their passive emotional response and their inferior intellectual reflections reveal the inaccessibility of the utopia described and the inability of the children to act upon the Soviet expectations presented for them.

Although Zhukov probably never intended to discourage his young readers, his writing appears to do exactly that. The Soviet expectations in 1924 were not actually unrealistic; Soviet leadership envisioned the construction of socialism by the masses of working people,[38] not an alien land of supermen. Lenin had warned people against the error of viewing Soviet power as a “miracle-working talisman,”[39] as he pointed out that the eradication of capitalism and the organization of socialism would not happen overnight.[40] Zhukov did exactly what Lenin considered to be erroneous. His counterproductive highlighting of the heroes’ reactions only made those ideals less possible to attain. Zhukov did not channel educational goals into practical guidelines, which might have been achieved by showing the children from 1924 doing the physical exercises from 1957, devoting themselves to studying science, and reaching out to international children with the purpose of achieving international communism.

Socialist Realist children’s literature from the Stalinist era more clearly aligned itself with communist ideology and authoritarian methods. Under Socialist Realism, authors often established a child hero who possessed all the desirable characteristics of a Young Pioneer, accomplished heroic deeds, and became the glory of the Communist Children’s Organization. In Mikhail Doroshin’s “Pavlik Morozov” (1933), for example, the teenage farm boy Pavlik sacrificed his life to denounce his father for hoarding grain seeds, a kulak[41] behavior condemned by the Soviet state.[42] Doroshin aimed to portray Pavlik as an orthodox communist model for children and a leader among the Pioneers. This goal is clearly revealed by Doroshin’s details on Pavlik’s leadership among his peers and his loyalty to the Soviet state.[43]

Voyage, by contrast, represented an experimental era of Soviet pedagogy for primary education. It was a time characterized by ambitious goals, with a still-uncertain educational system in which pedagogues and authors were “trying to figure out how its citizens should behave and feel.”[44] Unlike the Stalinist era, a time when pedagogical exploration in literature was largely terminated and replaced by the Socialist Realist story-telling formula, early Soviet education was haunted by uncertainty and experiments. Evaluating the Socialist Realist education as effective is not to say that the imposition of communist ideals is universally good. Rather, pedagogy under Stalin helps reveal the disconnection between authoritarian expectations and an educational system that encouraged individualism and fantasy in the early Soviet Union.

Vladimir Mayakovsky’s children’s book, Whom Shall I Be? (1932), offers another example. Although avant-garde artists and writers like Mayakovsky were never favored by Lenin, their work sincerely promoted the Soviet to children. Mayakovsky’s poem is also propaganda for the Soviet mandate, suggesting that children take up professions needed to modernize the Soviet state. Among the eight different professions he describes, Mayakovsky suggests that children could become doctors who can heal sick children.[45] This resonates with the Soviet agenda of raising a population of physical stoutness and universal healthiness. To echo the Soviet ambition of becoming a leading aviation state, he suggests children become airmen and go “to the stars and to the moon.”[46]

The long poem Whom Shall I Be? reflects Mayakovsky’s attempts to offer not just a list of professions demanded by the Soviet Union, but their rank of eminence for the state. However, the avant-garde poem structure could confuse children’s memorization of such a ranking.

Besides the introduction and conclusion, the poem is composed of eight main stanzas, each describing one profession and each approximately equal in length. However, Mayakovsky by no means suggests equality in the state’s demand for these jobs. He deliberately places the eight stanzas in an order that coincides with the relative importance of these professions to state-building. He first introduces manufacturing sector jobs like that of carpenter, continues with public service jobs such as doctor, and ends with pilots and sailors—the guardians of state sovereignty, which was of top national concern. (The highest distinction of military service personnel is not hard to see from the “Hero of the Soviet Union” award granted by the Soviet regime from 1934 to its fall in 1991.[47] Originally named the “Order of Lenin,” it was the highest recognition of Soviet citizens’ heroic feats for the state and society. Naval officers and pilots were frequent recipients of this award.[48]) The transition line between every two consecutive stanzas follows the same structure: Profession A is good (хорошо), but Profession B is better (лучше).

Столяру хорошо, A carpenter is good,

а инженеру – but an engineer is

лучше, better,

я бы строить дом пошел, I would go build a house,

пусть меня научат.[49] as long as you teach me.

The order of the two professions was unlikely a result of Mayakovsky’s poetic arrangement so that two consecutive stanzas rhyme with each other. The flexibility of Russian cases allows any two nouns to rhyme. Carpenter (cтоляру) rhymes with engineer (инженеру) by dative suffixes;[50] chauffeur (шофером) rhymes with pilot (летчиком), which follows it, by the use of instrumental case.[51] Therefore, Mayakovsky’s reason for arranging the eight professions in such an order is very likely to reflect and resonate with the state-ranked job preference.

Nevertheless, the intended message is undermined by the disruption of memorization power through Mayakovsky’s use of the avant-garde stepladder structure. A poetic line-arrangement invented by Mayakovsky himself, a stepladder is a single verse split over multiple lines, each starting spatially where the previous one left off.[52] Russian poetry expert Robert Bird suggests that Mayakovsky always used staggered verses to allow children to “take language apart” and “put it back together in new ways” and cites Whom Shall I Be? as an example.[53]Although when memorizing the poem, Soviet children might have not been encouraged to play with the verses, the flexible nature of the stepladder could readily confuse them. A child could mis-memorize the order of engineer and carpenter without noticing the mistake:

Инженеру хорошо, An engineer is good,

а cтоляру – but a carpenter is

лучше.[54] better.

This is because rhyme-wise, the misspoken version flows just as well as the original. With the convenience to rearrange lines and stanzas, misplacements of other professions and descriptions could regularly occur. The importance of state-determined rank of profession is offset by the avant-garde poetic structure, which weakens the potential of the poem to be used as an educational tool.

Lenin was always aware of the threats that modernist art would pose to his education agenda. As the literature expert Professor Clive Bloom suggests, Lenin considered Futurism and other forms of modernism “all disconnected [and] difficult to read.”[55] Lenin raged that “[t]he revolution does not need buffoons playing at revolution,[56]” pointing the finger directly at what he considered the flamboyant and idiosyncratic style of Mayakovsky’s writings.

Lenin believed that “there must grow up a really new, great communist art which will create a form corresponding to its content.”[57] In other words, he recognized the importance of matching the agenda with the appropriate educational methodology for the masses. Unfortunately, Lenin was never able to offer a theory of proletarian culture.[58]

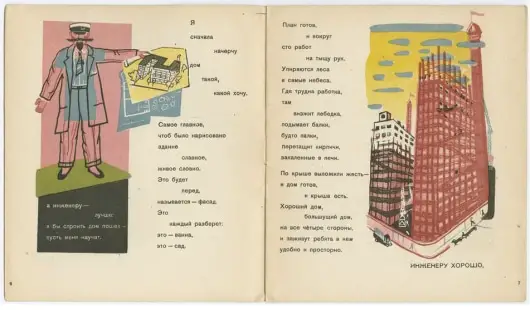

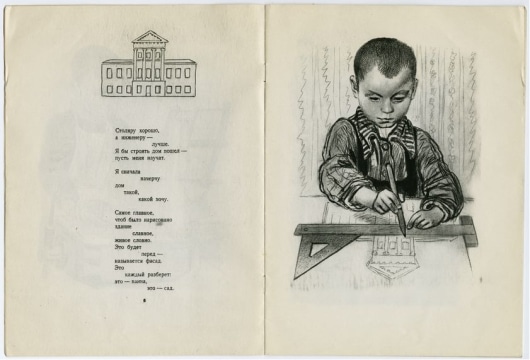

The overplaying of fantasy, as in Voyage, can also be seen in Whom Shall I Be? via a comparison of the poem’s 1932 illustrations with the 1947 version. One professional option mentioned in the poem, an engineer, was depicted in 1932 (the year that Socialist Realism just started to be the official state policy in the USSR) as a semi-transparent, mustachioed man symbolically holding a blueprint and a drawing of a building (Figure 1). On the opposite page was an extravagant drawing of a fully constructed building that looked almost “Frank Gehry-like,”[59] with an extremely fanciful constructivist style common to the rest of the poem’s illustrations. The Soviet expectations for children to modernize the country, rather than being reinforced with practical direction, were further abstracted and made dream-like by the pictures.

The 1947 Stalinist publication of the poem used very different illustrations (Figure 2). The realistic black-and-white pencil drawings showed how one becomes a professional, not a fanciful depiction of being a professional. For the same stanza concerning engineers, the symmetrical image of the school building on one page, and an image of a child sketching a classicist building with rulers and blueprint paper on the opposite page, reflected the clearly defined Soviet pedagogy of how and even where individual children should behave, study, and strive for their future professions.

Illus. by A. Pakhomov. Moscow, Leningrad:

Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo detskoi literatury, 1947.

web

In conclusion, while it is true that children’s creativity and individuality were tamed and discouraged under Stalin’s Socialist Realism, the Socialist Realist style prevailing in the later edition made it a more effective pedagogical tool for the communist state to achieve its stated goals.[60] On the other hand, literature about children and children’s literature from the post-civil war era, though rigorously promoting the state’s political agenda and the Soviet expectations for children, were either confusing or impractical as pedagogical tools. The Diary of a Communist Schoolboy described the incompatibility of an individualist-oriented, Western pedagogy with an attempt to achieve authoritarian expectations. Voyage gave no practical advice to children and instead created an inapproachable communist utopia. Whom Shall I Be? undermined the its potential use as an education tool with its unconventional poetic structure and, in its first edition, promoted a dream-like fantasy over practical achievements in its illustrations. All of these books closely paralleled the experimental and exploratory characteristics of the early Soviet educational system, in which Soviet leaders were still uncertain of what they should ask of Young Pioneers to help in building the Soviet society of the future.

Works Cited

Bird, Robert. “Vladimir Mayakovsky.” Adventures in the Soviet Imaginary: Children’s Books and Graphic Art. The University of Chicago Library. Web. 12 Dec. 2011.

<http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/webexhibits/sovietchildrensbooks/mayakovsky.html>.

Bloom, Clive. “Children of Albion: Dr Leavis amongst the Dongas Tribe.” Clive Bloom. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.clivebloom.com/Children Of Albeon.htm#_ftn4>. A version of the article was originally published in Chapter 9 of Literature, Politics and Intellectual Crisis in Britain Today. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001.

Chamberlin, William Henry. “The Revolution in Education and Culture.” Soviet Russia: A Living Record and a History. Boston: Atlantic Monthly, 1930. Marxists Internet Archive. Marxists Internet Archive. Web. 12 Dec. 2011. <http://www.marxists.org/archive/chamberlin-william/1929/soviet-russia/ch12.htm>.

“Dalton Plan.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.. 24 Jul 2012. Web. 28 Aug 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalton_Plan>.

“Декрет Совета Народных Комиссаров об отделении церкви от государства и школы от церкви (The Decree on the Separation of Church and State and School from Church).” Русская Православная Церковь в советское время (Russian Orthodox Church in the Soviet Era). Book 1. Составитель Гера Штриккер (Complied by Gera Shtrikker). Moscow: 1995. Published by “ПРОПИЛЕИ”. pp.113-115.

Doroshin, Mikhail. “Pavlik Morozov.” Mass Culture in Soviet Russia: Tales, Poems, Songs, Movies, Plays, and Folklore, 1917-1953. Indiana UP: Bloomington, 1995. 153-154. Print.

Foley, Kerry. “Literacy and Education in the Early Soviet Union (Viewpoint).” Portalus.ru. Web. 20 Sep. 2007. <http://www.portalus.ru/modules/english_russia/print.php?subaction=showfull&id=1190296667&archive=&start_from=&ucat=22&category=22>

Kott, Ruth E. “Illustrated Ideology.” The University of Chicago Magazine. Web Aug 2011.

<http://mag.uchicago.edu/arts-humanities/illustrated-ideology>

Kott, Ruth E. “Soviet Children’s Books Show Changing Ideology.” The University of Chicago Library News. University of Chicago Magazine, 15 July 2011. Web. 12 Dec. 2011.

<http://news.lib.uchicago.edu/blog/2011/07/15/soviet-children’s-books-show-ideology-illustrated/>.

Lenin, Vladimir. How the Working People Can Be Saved From the Oppression of the Landowners and Capitalists For Ever. Rec. Mar. 1919. V. I. Lenin Library. Manuscript: Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th English Edition, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1972. Vol. 29, pp. 248-249. Web. 29 Sept. 2012.

<http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/speeches/working-people.htm>.

Lenin, Vladimir. On Labor Discipline. Rec. Mar. 1919. V. I. Lenin Library. Manuscript: Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th English Edition, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1972. Vol. 29, pp. 250-251. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/speeches/labour.htm>.

Lenin, Vladimir. What is Soviet Power? Rec. Mar. 1919. V. I. Lenin Library. Manuscript: Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th English Edition, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1972. Vol. 29, pp. 248-249. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/speeches/soviet-power.htm>.

“Lenin’s Speeches on Gramophone Records.” Rec. 1919-1921. First Published: according to the gramophone records. Organization of these speeches was accomplished by Tsentropechat, the central agency of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee for the Supply and Distribution of Periodicals. Between 1919 and 1921, 13 of Lenin’s speeches were recorded. <http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/index.htm>.

Маяковский, Владимир. “Кем Быть?” Владимир Маяковский стихи. Пётр Соловьёв. Web. 12 Dec. 2011. <http://www.stihi-rus.ru/1/Mayakovskiy/66.htm>.

Nearing, Scott. The Making of a Radical: A Political Autobiography. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2000. Print. pp. 308.

Ognyov, Nikolai. The Diary of a Communist Schoolboy. Trans. Alexander Werth. New York: Parson & Clarke Limited, 1928. Print.

Prokhorov, Aleksandr Mikhailovich. Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Volume 6. New York: Macmillan. pp. 594.

Vladimir Lenin in Clive Bloom. “Children of Albion: Dr Leavis amongst the Dongas Tribe.” Clive Bloom. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.clivebloom.com/Children Of Albeon.htm#_ftn4>. A version of the article was originated published in Chapter 9 of Literature, Politics and Intellectual Crisis in Britain Today. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001.

Wachtel, Michael. The Development of Russian Verse: Meter and Its Meanings. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP 1998. Print. pp. 206

Yue, Feng. The History of Orthodox, 2nd Edition. China Social Sciences Publishing House: Beijing, 1996. Print. pp. 188-191.

Zhukov, Innokenty. “Voyage of the Red Star Pioneer Troop to Wonderland.” Mass Culture in Soviet Russia: Tales, Poems, Songs, Movies, Plays, and Folklore, 1917-1953. Indiana UP: Bloomington, 1995. 90-112. Print.

Footnotes

[1] Foley, Kerry. “Literacy and Education in the Early Soviet Union (Viewpoint).” Portalus.ru. Web. 20 Sep. 2007. <http://www.portalus.ru/modules/english_russia/print.php?subaction=showfull&id=1190296667&archive=&start_from=&ucat=22&category=22>

[2] Lenin, Vladimir. How the Working People Can Be Saved From the Oppression of the Landowners and Capitalists For Ever. Rec. Mar. 1919. V. I. Lenin Library. Manuscript: Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th English Edition, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1972. Vol. 29, pp. 248-249. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/speeches/working-people.htm>.

[3] “Lenin’s Speeches on Gramophone Records.” Rec. 1919-1921. First Published: according to the gramophone records. Organization of these speeches was accomplished by Tsentropechat, the central agency of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee for the Supply and Distribution of Periodicals. Between 1919 and 1921, 13 of Lenin’s speeches were recorded. <http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/index.htm>.

[4] Lenin, Vladimir. On Labor Discipline. Rec. Mar. 1919. V. I. Lenin Library. Manuscript: Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th English Edition, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1972. Vol. 29, pp. 250-251. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/speeches/labour.htm>.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Nearing, Scott. The Making of a Radical: A Political Autobiography. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2000. Print. pp. 308.

[7] Ibid. 104.

[8] Ibid. 110-111.

[9] “Dalton Plan.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.. 24 Jul 2012. Web. 28 Aug 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalton_Plan>.

[10] Parkhurst, William P. “Educator Extraordinary.” The Parkhurst Family Journal 1.4 (1995): 1-10. The Parkhurst Family. Web. 28 Aug. 2012. <http://www.parkhurstfamily.org/journal/Volume1_Number4.pdf>. pp. 3.

[11] “Dalton Plan.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.. 24 Jul 2012. Web. 28 Aug 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalton_Plan>.

[12] Ognyov, Nikolai. The Diary of a Communist Schoolboy. Trans. Alexander Werth. New York: Parson & Clarke Limited, 1928. Print.

[13]Ibid., pp. 16.

[14] Ibid., pp. 12.

[15]Ibid., pp. 103.

[16] Ibid., pp. 61.

[17] Ibid., pp. 12.

[18] Ibid., pp. 14.

[19] “Декрет Совета Народных Комиссаров об отделении церкви от государства и школы от церкви (The Decree on the Separation of Church and State and School from Church).” Русская Православная Церковь в советское время (Russian Orthodox Church in the Soviet Era). Book 1. Составитель Гера Штриккер (Complied by Gera Shtrikker). Moscow: 1995. Published by “ПРОПИЛЕИ”. pp.113-115.

[20] Yue, Feng. The History of Orthodox, 2nd Edition. China Social Sciences Publishing House: Beijing, 1996. Print. pp. 188-191.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Декрет Совета Народных Комиссаров об отделении церкви от государства и школы от церкви (The Decree on the Separation of Church and State and School from Church).” Ibid.

[24] Zhukov, Innokenty. “Voyage of the Red Star Pioneer Troop to Wonderland.” Mass Culture in Soviet Russia: Tales, Poems, Songs, Movies, Plays, and Folklore, 1917-1953. Indiana UP: Bloomington, 1995. 90-112. Print. pp. 104.

[25] Ibid., pp. 93, 94.

[26] Ibid., pp. 101.

[27] Ibid., pp. 101.

[28] Ibid., pp. 104.

[29] Ibid., pp. 107,110.

[30] Ibid., pp. 104.

[31] Ibid., pp. 104.

[32] Ibid., pp. 104.

[33] Ibid., pp. 98.

[34] Ibid., pp. 103, 105.

[35] Ibid., pp. 102.

[36] Ibid., pp. 99.

[37] Ibid., pp. 105.

[38] Lenin, Vladimir. What is Soviet Power? Rec. Mar. 1919. V. I. Lenin Library. Manuscript: Lenin’s Collected Works, 4th English Edition, Progress Publishers. Moscow. 1972. Vol. 29, pp. 248-249. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.marxists.org/romana/audio/speeches/soviet-power.htm>.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] In the early Soviet Union, peasants who were relatively wealtheir were considered class enemies of poorer farmers. Lenin calls kulaks “bloodsuckers, vampires, plunderers of the people and profiteers, who fatten on famine.” (Lenin, Vladimir I. “Comrade Workers, Forward To The Last, Decisive Fight!” Rabochaya Moahva 14 (1925) in Lenin’s Collected Works. Trans. Jim Riordan. Vol. 28. Moscow: Progress, 1965. 53-57. V.I.Lenin Internet Archive. Web. 28 Aug. 2012. <http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1918/aug/x01.htm>.)

[42] Doroshin, Mikhail. “Pavlik Morozov.” Mass Culture in Soviet Russia: Tales, Poems, Songs, Movies, Plays, and Folklore, 1917-1953. Indiana UP: Bloomington, 1995. Print. pp. 153-154.

[43]Ibid., pp. 154.

[44] Kott, Ruth E. “Soviet Children’s Books Show Changing Ideology.” The University of Chicago Library News. University of Chicago Magazine, 15 July 2011. Web. 12 Dec. 2011. <http://news.lib.uchicago.edu/blog/2011/07/15/soviet-children’s-books-show-ideology-illustrated/>.

[45] Маяковский, Владимир. “Кем Быть?” Владимир Маяковский стихи. Пётр Соловьёв. Web. 12 Dec. 2011. <http://www.stihi-rus.ru/1/Mayakovskiy/66.htm>. ll. 83-115

[46] Ibid. ll. 232-234

[47] Prokhorov, Aleksandr Mikhailovich. Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Volume 6. New York: Macmillan. Print. pp. 594.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid. ll.39-43

[50] Ibid. ll. 39, 40

[51] Ibid. ll. 213, 214

[52] Wachtel, Michael. The Development of Russian Verse: Meter and Its Meanings. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998. Print. pp. 206

[53] Bird, Robert. “Vladimir Mayakovsky.” Adventures in the Soviet Maginary [Imaginary?]: Children’s Books and Graphic Art. The University of Chicago Library. Web. 12 Dec. 2011. <http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/webexhibits/sovietchildrensbooks/mayakovsky.html>.

[54] Sentence structure adapted from Mayakovsky’s Whom Shall I Be?. (ll. 39-41)

[55] Vladimir Lenin in Clive Bloom. “Children of Albion: Dr Leavis amongst the Dongas Tribe.” Clive Bloom. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.clivebloom.com/Children Of Albeon.htm#_ftn4>. A version of the article was originated published in Chapter 9 of Literature, Politics and Intellectual Crisis in Britain Today. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Bloom, Clive. “Children of Albion: Dr Leavis amongst the Dongas Tribe.” Clive Bloom. Web. 29 Sept. 2012. <http://www.clivebloom.com/Children Of Albeon.htm#_ftn4>. A version of the article was originated published in Chapter 9 of Literature, Politics and Intellectual Crisis in Britain Today. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001.

[59] Bird, Robert in Ruth E. Kott. “Illustrated Ideology.” The University of Chicago Magazine. Web Aug 2011. <http://mag.uchicago.edu/arts-humanities/illustrated-ideology>

[60] Ibid.