The Kunstkamera is a distinctive blue building set along the Nevsky on Vasilievskiy Island. Among its many claims to fame, the most prominent is that the Kunstkamera was the first museum created for the public in Petersburg; it was established by Peter the Great to house his collection of curiosities.

Peter the Great was a renaissance man, whose many interests included medical sciences, and the Kunstkamera attests to this. The name “kunst-kamera” comes from the Dutch and means “art room.” The phrase was first coined by a surgeon. In its conception, the idea of the “Kunstkamera” itself was tied to the union of art and science. Peter’s collection within his art-room museum was intended to educate the populace as well as entertain. For instance, he made malformed embryos of various species the first exhibit in order to prove to the superstitious Russian people that birth defects were a scientific phenomenon, not something caused by God’s will or mystic forces, by showing the variety of defects and the variety of animals they appeared in.

Peter hoped an artistic presentation of his accumulated curiosities would help draw the populace yet also show show that museums could be refined and something that the nobility would also benefit from visiting, to see and discuss the ideas imparted there.

The Kunstkamera has since been converted partially into an ethnographic museum, but it still houses many of Peter the Great’s collections. The displays themselves are arranged historically, in styles of showcasing that are by no means modern, in order to give the museum a historic feeling in its displays and help transport the visitor back in time to see the exhibits with a historical lens.

On the second floor of the Kunstkamera sits a very unique exhibit, arranged unusually and of unusual subject matter for an ethnography museum, the preserved first exhibition of Peter the Great. The exhibit is on teratology, the study of embryonic malformations, and contains a wide array of preserved fetuses, spanning multiple species (from chicken to human) and multiple potential defects (from cyclopes to those with five limbs), situated next to other found curios.

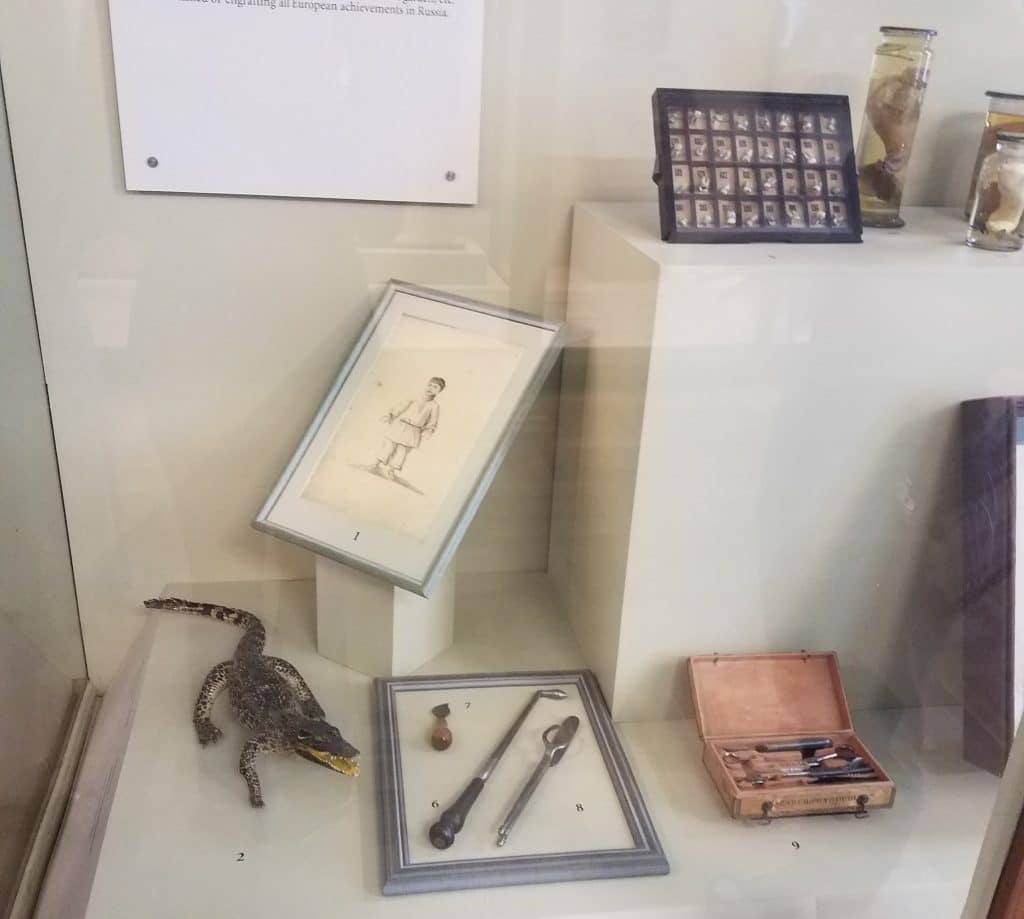

The arrangement of displays in this hall diverts the exhibit from something purely scientific into a blend of science and artistic presentation that was common in the 18th century. Alongside a glass case containing a preserved limbless infant and cyclops piglet sits a perfectly normal stuffed echidna and an arrangement of starfish from the tropics. Next to jars of baby limbs stands an alligator and some of Peter’s personal medical instruments.

The blending of aesthetic and medical aspects of displays being preserved rather than rearranging the displays to contain only immediately related objects (wet specimens with other wet specimens, stuffed animals with others of their kind) preserves the historical feeling of the museum. It adds the dimension of seeing into the 18th century alongside seeing scientific curios of an emperor.

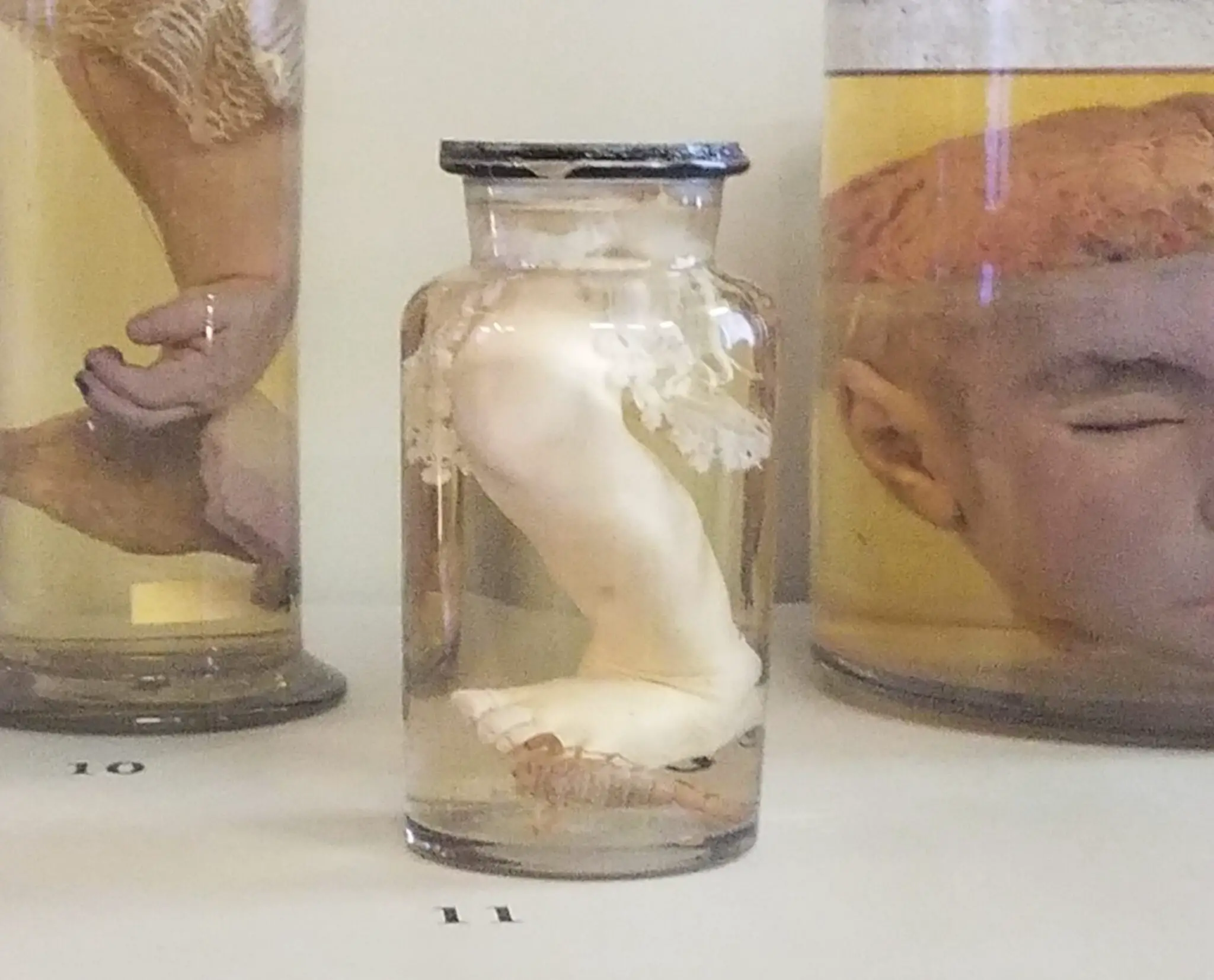

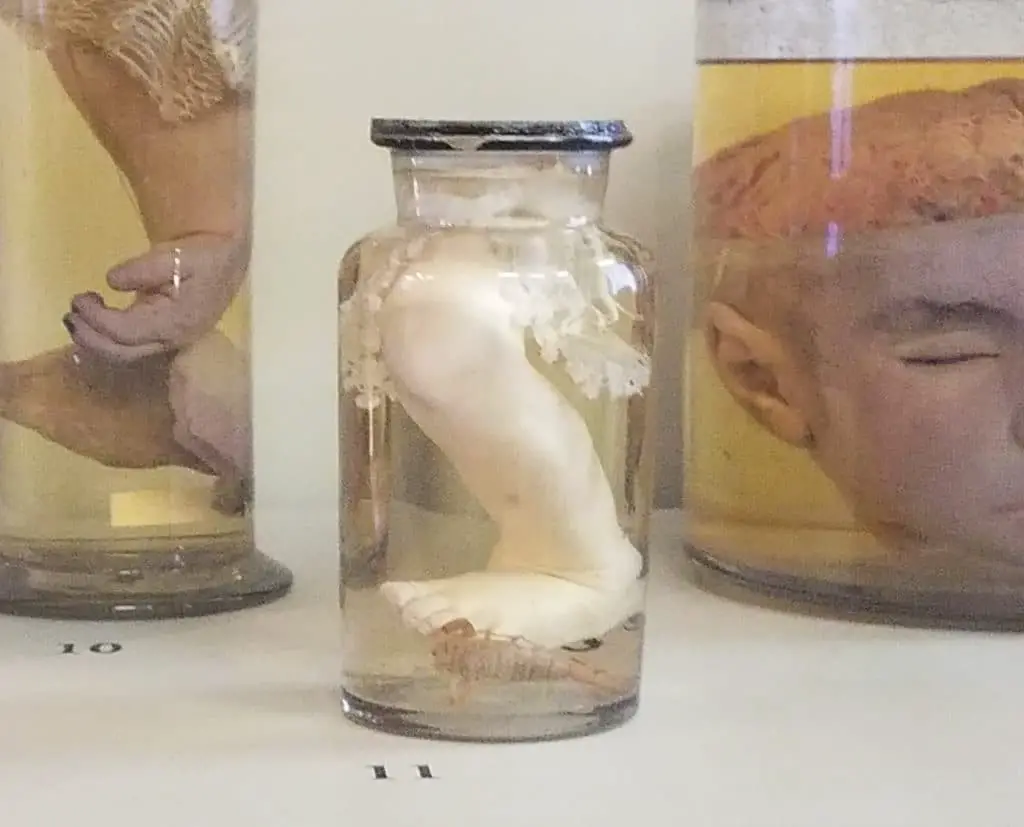

One individual item in particular encapsulates this 18th century idea of combining art and science in a single display. In a case featuring the “Peter’s Interests” sits a jar labelled “no.11,” containing an amputated infant leg with a skirt of lace tied around the site of amputation and a preserved scorpion added into the jar of formaldehyde with the leg. The scorpion, to the best knowledge of the museum, has nothing to do with how the leg parted ways from its original owner. Instead, both scorpion and lace were added to the specimen to give it artistic value.

Scorpions in art symbolize contrasts, most notably that of life and death, and an ambivalent balance between them. The symbol fits nicely within a preservation of a dead leg that still looks as it would in life, the scorpion artistically emphasizes that balance. The scorpion is also a very delicate arachnid, possessing its own sort of carapaced beauty; the delicate body and the precise articulated joints contract starkly with the rounded, less delicate limb of the infant it is presented next to.

The lace was added to the leg in order both to provide beauty and to cover the less-presentable site of amputation. While a medical student would, in all likelihood, wish to see the cut in order to ascertain exactly how and where it was done and see what a good or bad amputation site would look like, it is the demographic of artist who would wish to see a disembodied limb with the open flesh covered and something delicate added to go along with the shape and idea of the infant from whom the leg came. Its combination of delicacy and domestic beauty also contrasts the practical fattiness of the baby’s leg and the beautifully frightful arachnid it is placed with, creating a triad of aesthetics and types of beauty— the deadly, the human, and the textile.

The additives do not make an artful presentation out of a scientific presentation by their presence alone; they make an artful presentation from symbolism and care in preparation. The artistic exists alongside the scientific and both are considered in these museum specimens to create a unique and beautiful exhibition of 18th century scientific thought.

The teratology exhibit at the Kunstkamera uses its historical site status and old-fashioned pieces to full advantage, making a wholly unique and fascinating display that can be appreciated on all spectra, from artistic to historical to scientific. Their exhibits are not only about the curios, not only about Peter’s activities in the 1700s, but what kind of worldview the exhibitions presented at their time of creation. The glimpse into the mindset of Peter the Great that this exhibit gives shows the inextricable connection between arts and the sciences, how both considered one another and were presented to laymen in harmony.

Kunstkamera

Universitetskaya Naberazhnaya, 3

Website