Aristarkh Lentulov was born in 1882 in the town of Nizhny Lomov, near Penza. His father, a rural priest, died just two years later, survived by his wife and four children. Lentulov was educated first at the religious school at Penza (where drawing became his favorite hobby) and, later, at the local seminary. Although the family struggled financially, when Penza Art College opened in 1898, he enrolled. After two years of study, he moved nearly 750 miles west to study at the Kiev School of Art, where he took a particular interest in the portrayal of light and color in painting. He later left the school with a group of like-minded student artists who wanted to find a better way to develop their styles away from traditional techniques and styles.

Lentulov failed to pass his entrance exams at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts in 1907, but his bold style and his confidence in his work caught the attention of others, including artist, illustrator, and stage designer Dmitry Kardovsky. For two years, Lentulov studied in Kardovsky’s private studio in St. Petersburg. He went on to study at the Académie de la Palette and at the studio of Henri Le Fauconnier in Paris. Although he experimented with Fauvism, Post-Impressionism, and Cubism, Lentulov developed his own distinctive, colorful, Futurist-influenced style that earned the nickname “Futurist a la Russe” (The Russian Futurist) amongst his Parisian contemporaries. He is often credited with initiating the Russian art movement of Cubo-Futurism.

He returned to Russia in 1909, but traveled extensively for the next few years, touring the popular art destinations of Italy, France, and Crimea. Between travels, he became intensely involved in the artistic life of Moscow—especially in the life of the avant-garde movement. In 1910, he co-founded the Jack of Diamonds group. Mikhail Larinov, another founding member, chose the name, which the group agreed upon as “a symbol of young enthusiasm and passion, for the knave implies youth and the suit of diamonds represents seething blood.”

The group’s first show had a twofold purpose: to promote the “new art,” and “to offer young Russian artists who find it extremely difficult to get accepted for exhibitions under the existing indolence and cliquishness of our artistic spheres, the chance to get onto the main road.” Although the Jack of Diamonds artists differed in style, they had in common their resentment of what they perceived as the narrow-mindedness of the traditional “fine art” world, a wish to break out of the confines of realism, and a shared love of the spontaneity and bright colors of traditional folk art.

The effort was met with mixed reactions, and the Jack of Diamonds group continued to struggle with negative reviews throughout their seven years of exhibitions. A conservative reviewer for the The Moscow Sheet, a newspaper that was widely published and distributed throughout the empire, described the first exhibition as “a colorful mess–the product of a decaying brain,” but others had more positive responses. Benois (founder of the World of Art movement and magazine) admired Lentulov’s bright paintings, which “sing and cheer the soul.” Russian symbolist poet Maximilian Voloshin, whom Lentulov later befriended in Crimea, wrote the review for the Russian Artistic Chronicle. Of the artists, he stated that: “Mashkov, Lentulov, Konchalovsky, Larionov, Goncharova…(are) different in temperament, but form one coherent group. They have a beautiful instinct, they are talented, they are boldly sincere….”

In 1912, Lentulov’s travels inspired a new era of his work. While visiting Italy, he was deeply impressed by Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” and the large-scale works of Titian and Veronese. Later that year, while visiting the town of Koktebel in Crimea, he accepted a commission to paint a mural in a local café. One wall was to be filled with caricatures of local inhabitants of the town. Working on this large scale project after seeing the works of the great Italian Renaissance masters inspired Lentulov to begin his own series of monumental paintings.

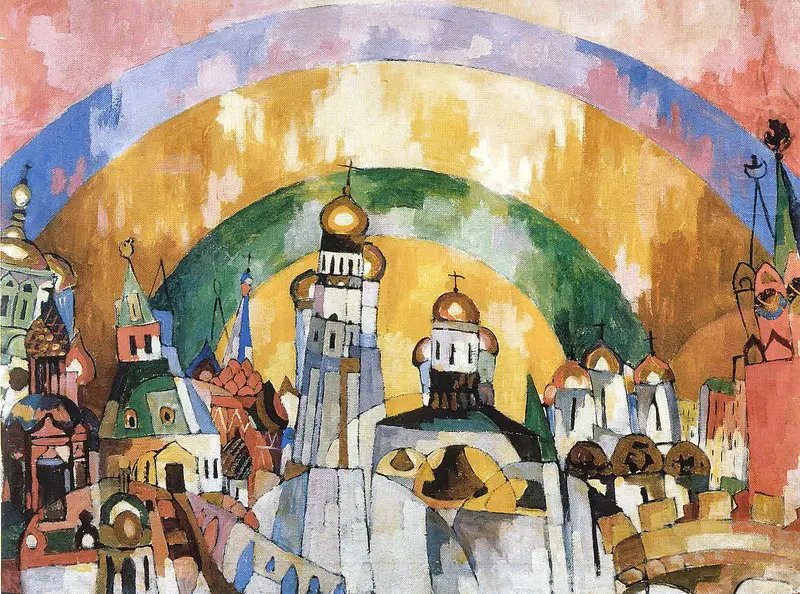

The first of this series, “Allegory of the Patriotic War of 1812,” was a celebration of the 100th anniversary of Russia’s victory over Napoleon, and is one of the first examples of Cubo-Futuristic painting in Russia. It was also the first of many large-scale works in which Lentulov sought to fuse the strength and beauty of historic Russia with the brilliant colors and kaleidoscopic forms for which both modern and Russian folk art are known.

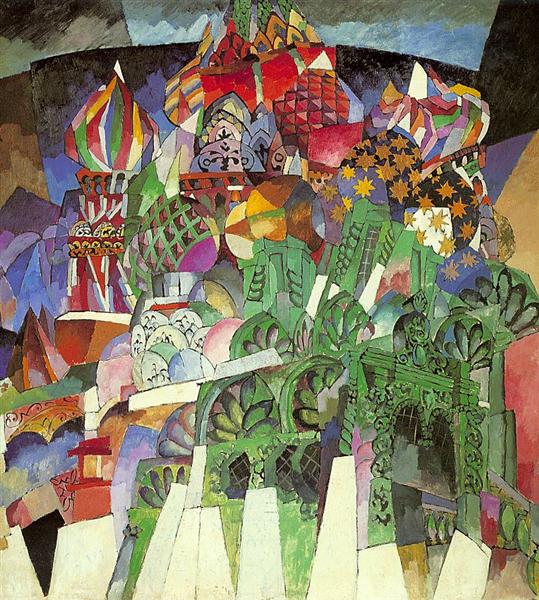

Perhaps Lentulov’s best-known painting, “St. Basil’s Cathedral,” another example from the series, was painted the following year. The use of Cubist techniques allowed Lentulov to portray “every part of the cathedral at the same time.” His daughter wrote, “He went around the cathedral dozens of times trying to remember its strange angles ‘in order to make it a boundless fantasy worthy of fairy tales in terms of shapes and colours.'”

The sense of color and movement in this series of Lentulov’s works, as well as his incorporation of multimedia (the addition of gold leaf, fabrics, and even pasted wood carvings into his paintings), made him a natural candidate for theatrical set design work.

Beginning in 1916, Lentulov designed sets for Kamerny Theater, the Bolshoi Theater, the Moscow Chamber Theater, the Moscow Soviet Theater of Opera, and more. His design for the Bolshoi Theater’s performance of Alexander Scriabin’s symphonic poem “Prometheus” included both the backdrop and the lighting design. The spectacle Lentulov produced, using filtered floodlights and colored spotlights which changed according to the tone of the music–not unlike the light shows one expects at a modern-day rock concert–dazzled the “Prometheus” audience.

The last exhibition shown under the Jack of Diamonds name was an effort to raise funds for the new Bolshevik government’s war effort in 1917. After a 1917 World of Art Exhibition, art critic Abram Efros wrote that the group was, “now a shell without the corresponding content, filling the empty space with the most diverse jumble….Yet as Benois himself once defined the aims of the World of Art as being an eclectic bazaar of talents, perhaps what is happening is extremely desirable and a form of transfusion of fresh blood into decrepit veins.”

As for Lentulov, he hardly seemed held back by the dissolution of the Jack of Diamonds, nor by any doubts of critics. In the 1920’s, he helped found the Moscow Painters and the Society of Moscow Artists, as well as joining the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia and serving on the academic council of the Institute of Artistic Culture. During this period, he began teaching at the High State Art Technical Institute and the Moscow Institute of Fine Arts, as well as teaching free workshops around Moscow.

Lentulov was also later involved in decorating Moscow for Soviet national celebrations such as May Day and the anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution.

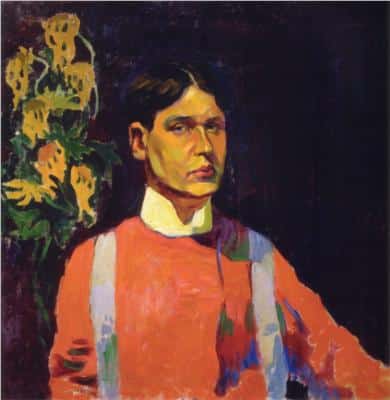

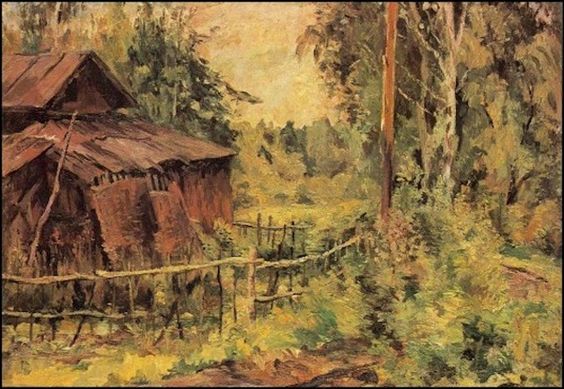

Lentulov’s artwork changed during the 1920’s and 1930’s, as well, beginning with his 1919 “Self-Portrait with Violin.” He worked on smaller canvases, and although he kept his use of intense color, he moved toward a more post-impressionistic style. His Cubo-Futurist architectural landscapes gave way to traditional landscapes with a focus on the viewer’s sense of space and light. Many of his works at this time were views from his studio windows.

Lentulov held a solo exhibition showing a retrospective of his life’s work in 1933. Afterward, he traveled extensively around the country, looking for scenes to inspire his final series of work, which focused on industrialization. Among other things, he did a series of sketches and paintings on the construction of the Moscow Metro.

In 1942, Lentulov returned to Moscow where he died on April 18, 1943 after a protracted illness. He is buried in Moscow’s Vagankovo Cemetery.

It is difficult to categorize Lentulov into any one movement, partly because of his adaptability and the evolution of his work over time, but also because he was involved in the inspiration of so many of his contemporaries who subsequently branched out in their own directions to define new movements. Certainly his work in the mid 1910’s is his most famous, and showcases his abilities as a Cubo-Futurist. However, Lentulov’s work is so fresh, so original, that no one label quite captures it–a fitting and satisfying legacy for any avant-garde artist.

More information:

Art of Russians: Aristarkh Lentulov (very inclusive gallery of his work)

The Russian Experiment in Art 1863-1922 (Revised Edition) (World of Art)

The Avant-Garde Frontier: Russia Meets the West, 1910-1930