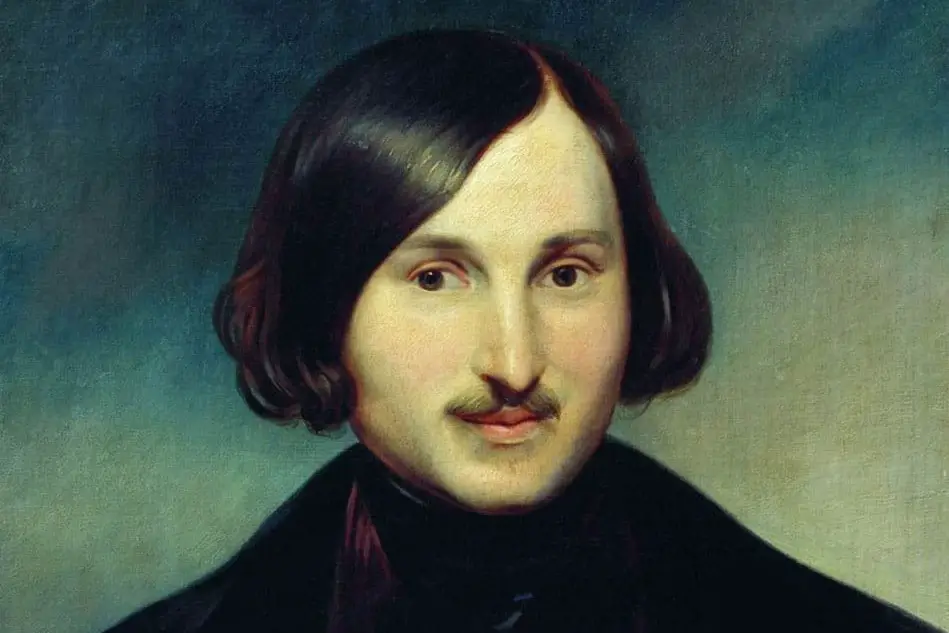

Nikolai Gogol’s “The Portrait” is a short story about art. First written in 1835 and then significantly revised in 1842, the work explores a central concern in Romantic aesthetics: the role of the artist and his creation. Through a series of ekphrases, i.e. literary representations of visual art, the narrative of “The Portrait” examines the act of representational painting in all of its constituent parts: the psychological condition of the artist, the manner of painting (or its formal qualities), the possible subjects of representation, and, finally, its impact upon the viewer.

Works of art appear successively in the story as objects of amusement, labors of love, vanity props, commodities, and even acts of divine creation. In an effort to help sort through Gogol’s complex thoughts on aesthetics, this study will provide historical context for “The Portrait” within contemporary Russian discourse on iconography. Focusing on the similarities between Gogol’s portrait of the moneylender and the Russian icon, I will argue that the narrative of “The Portrait” betrays an apprehension over the painted image, which is principally a religious concern that emerged out of the 1666 schism in the Russian Orthodox Church.

The first half of Gogol’s “The Portrait” recounts the story of a young, poor but promising artist named Chartkov who purchases a striking portrait from an art dealer in a local market. The next day he miraculously discovers thousands of gold roubles hidden in its frame. Chartkov thereafter abandons his study of art and uses the money to purchase himself artistic fame, surrendering his brush to the popular fashions of the day. Later in life, Chartkov encounters a work of true artistic genius by one of his contemporaries. Seeing that his own youthful talent was lost, he realizes the portrait was to blame and soon after dies an agonizing death. The reader learns in the second half of this work that the portrait was of a notorious moneylender, done by a pious artist who, in painting this portrait, loses his own artistic ability. Only after living for years as a hermit in a monastery is he able to paint again. The artist asks his son, who narrates much of the second half of the story, to destroy the portrait should he ever come across it.

The inspiration for this study comes from a quote by Robert A. Maguire:

Another Christian subtext [to “The Portrait”] is hinted at in the portrait of the moneylender, with his prominent eyes and confrontational manner. This reminds of figures in Orthodox icons, through which a divine power (or a demonic one, in Gogol’s case) enters the world.[1]

The “prominent eyes and confrontational manner” of icons to which Maguire rightly refers is well described by Father Steven Bigham:

… artistic techniques, such as inverse perspective, are used to enhance the feeling that the persons painted in icons are looking at us, addressing us, and penetrating us by their looks. How many people do not like icons or do not want to look at them, not for aesthetic reasons, but because they are unnerved by the penetrating look of holiness coming at them through the saints’ eyes?[2]

Characters in “The Portrait” react precisely the same way to the portrait of the moneylender. Its eyes draw in viewers and repel them simultaneously. In the opening scene from “The Portrait” in the Shchukin market, for instance, Gogol writes: “A woman who stopped behind him [Chartkov] exclaimed, ‘It’s staring, it’s staring!’ and backed away. He [Chartkov] felt some unpleasant feeling, unaccountable to himself, and put the portrait down.”[3] A close reading of the story reveals, however, that parallels between the portrait and Orthodox icons extend well beyond those that Maguire identifies. Not only does its appearance “remind” of icons, but its behavior in the story does, as well. Many of the seemingly miraculous events that regularly surround the portrait have parallels to the icon lore circulating in Russia in Gogol’s day.

We first learn of the portrait’s powers the very night Chartkov brings the painting home. As he falls asleep, Chartkov undergoes three dreams in succession: in the first, the moneylender crawls out from the portrait and unwraps heavy packets of roubles (350); in the second, he finds himself fixed before the portrait, while the features of the moneylender begin to move (351); and in the third, the moneylender begins to pull away with his hands the sheet that Chartkov had thrown over the portrait (351). Such dream sequences are a common motif in icon lore. The seventeenth-century clergyman, Paul of Aleppo, recorded in his chronicle, The Travels of the Patriarch Macarius of Antioch, that an important official dreamt three times in one evening of an icon that had been buried in a house. In the morning, he discovered the icon exactly where he dreamt it to be.[4] So too do Chartkov’s dreams prove prophetic. When the police inspector and landlord enter Chartkov’s room to force him to pay his rent, the inspector clumsily breaks the icon’s frame to reveal the very same packets of “1,000 Gold Roubles” (354) that Chartkov had dreamt of, thus saving him from eviction. Stories also existed in Gogol’s time about icons giving gold, with the Pecherskaya icon being the subject of many such stories.[5]

Also common from the seventeenth century onward were stories of icons that could “defend” themselves from destruction by fire or the sword.[6] Regularly evading its own demise, the portrait of the moneylender does the same. In one scene, the painter of the portrait “snatched the portrait of the moneylender from the wall, asked for a knife, and ordered a fire made in the fireplace, intending to cut it to pieces and burn it” (387). Yet just as he moves to “hurl it into the fireplace,” his friend cries out, “Stop, for God’s sake!… better give it to me” (387). The portrait escapes destruction here—and interestingly enough, its savior evokes the name of God in doing so. Again, at the end of the story, the son of the moneylender’s portraitist declares to a crowded auction that he swore to destroy the portrait, which was at that moment up for sale (392). Before he does so, however, the painting is suddenly stolen (393).

These similarities between the miracles that surround the portrait and Orthodox icons would not be lost on Gogol’s audience; for in Russian devotion and culture, the prominence of miracle-working icons cannot be overstated. Oleg Tarasov recounts the following story—from only a few years prior to Gogol’s first draft of “The Portrait”—that displays the ubiquitous nineteenth-century Russian belief in icons and their power to enact changes in this world:

… any such discovery of an icon in an unexpected place could be taken as a revelation. Thus it was in the 16th century, and also in the 19th. On 10 June 1831 someone placed an image of the Holy Trinity at the window of the Nikolskaya Church in Moscow’s Podkopayi district, and already by 5 a.m. a mass of people, growing hour by hour, was observed gathering around it… So that it could be ‘reliably observed’, the image had to be placed in the cathedral church of the Chudov Monastery in the Moscow Kremlin; no less than twice a month the monks were obliged to report all information about the ‘latest events’ concerning the icon.

Icons were not only purported to work miracles, but were even expected to do so on a daily basis. The Russian government recognized the presence of miracle-working icons and attempted to control their proliferation in Gogol’s time by requiring that clergy report every incident of a miracle-working icon to the Senate for investigation.[7]

The portrait of the moneylender thus exercises the sort of evil power that we come to expect from Gogol’s demons (such as those depicted in his story “Viy”), that of deception.[8] The devil in Gogol’s works is above all a character who is good in all appearance, but who in reality is evil.[9] After painting the moneylender, the portraitist finds himself helplessly reproducing the moneylender’s demonic eyes in all of his figures, “as if [his] hand was guided by an unclean feeling” (387), and then inexplicably suffers the death of his entire family (389). Once Chartkov becomes conscious that his youthful artistic talent was lost, he realizes that “this strange portrait, had been the cause of his transformation,” for it had “given birth to all the vain impulses in him” (372). Chartkov develops as a result a “cruel fever combined with galloping consumption,” loses his sanity and finally dies haunted by the images of portraits (373). It is also noted that another who owned the portrait for a short time was afflicted with insomnia and felt as if “some evil spirit” was strangling him (388).

Contrary to first inclinations, the reader cannot simply attribute these disastrous effects of the portrait to its subject matter of a cruel moneylender. The image of the moneylender was, in its very inception, to be used in a work recently commissioned by a local church (384). Gogol himself de-emphasizes the importance of the painting’s subject matter, for while “Christian subjects” are ultimately “the highest and last step of the sublime” (383), ignoble subject matter can also be spiritually uplifting (348).

Fear that a demonic painting could ruin the lives of all unfortunate enough to encounter it is characteristic of the Old Believers, a sect of Russian Orthodoxy that refused to acknowledge Patriarch Nikon’s reforms of the church in the mid-seventeenth century. Included in Nikon’s extensive reforms were the demands that (1) worshippers make the sign of the cross with three fingers, rather than two, and (2) the name Christ be abbreviated “IИC XC” instead of “IC XC.” Icons depicting saints holding their hand toward the viewer with two fingers, or images of Christ labeled with the latter abbreviation were suddenly illegitimate. Leonid Ouspensky remarks, “[symbolism] is essentially inseparable from Church art, because the spiritual reality it represents cannot be transmitted otherwise than through symbols.”[10] In other words, the correct symbols are necessary for believers to participate in the spiritual reality allowed by icons. A disagreement over symbols—in this case, the correct hand gesture and abbreviation of Christ’s name—thus was also a disagreement over who were members of the “true” Church.

The entire Russian Orthodox community was confronted after the reforms with the choice between two rival sets of Christian symbolism, that of the older icons retained by the Old Believers and that of the newer icons endorsed by the church ecclesiastical hierarchy and tsar. As a result, all Christian symbolism, once the popular source of consolation in prayer, suddenly became ambivalent. “The refusal of Patriarch Nikon and Tsar Aleksey Mikhaylovich to retain the old symbols,” Tarasov writes, “induced in the collective belief system a deep conviction of the gracelessness both of the ‘world’ of Muscovite Russia and of its new icons.”[11] In short, the Church and its symbols no longer offered a certain path to salvation. There was doubt as to whether Russia, once believed by Russians to be the “Third Rome” after the fall of Rome in the fifth century and then Constantinople in 1453, was in actuality the guardian of true Christianity in the world. During the 1870s, this fear over the ambiguity of symbols manifested itself in tales circulated by popular Russian newspapers of “hellishly drawn” icons. These icons had images of the devil on the backside and included such disquieting phrases as “‘bow down to me for seven years and you will be mine for eternity.'”[12] For Old Believers in particular, the result of the reforms was catastrophic: “Fear of accidentally encountering an image of the Anti-Christ was strengthened by the difficulty, or even impossibility, of recognizing it.”[13]

With this fear of the Old Believers’ in mind, we find that Gogol depicts the portrait as similar to what were the most highly regarded (and widely copied) icons of nineteenth-century Russia: those produced by the iconographer Andrey Rublyov (c.1360 – c.1430), whose work in the first half of the nineteenth century became popularly associated with Old Believer devotion.[14] The Rublyov style was commonly believed to be based on Greek technique, in which the coloration of the icon “had to be dark, ‘harsh’ and ‘obedient to higher goals.'”[15] In Greek countenances, these icons sought “exhaustion, gloominess, and mystery” with facial shading in dark red.[16] Gogol similarly describes the moneylender as having a “swarthy, lean, burnt face” of “a southern origin… Indian, Greek, Persian, no one could say for certain,” with a coloration that was “somehow inconceivably terrible” (378). He was “high-cheekboned, the features seem to have been caught at a moment of convulsive movement bespoke an un-northern force. Fiery noon was stamped on them” (343). In sum, the face of the moneylender with his dark coloration and striking features, his Grecian appearance, and the mystery surrounding his visage all suggest the Rublyov icons adored by Old Believers in Gogol’s day.

Finally, Old Believers were particularly disposed toward portraying images of demons in their iconography. As has been previously noted, Orthodox icons (Old Believer and New Ritualist alike) were not limited to depictions of Jesus, Mary, and the saints—demons were regularly painted. Yet for the Old Believers, as Tarasov writes, “the essential point is that the image of a hellish monster was often represented on Old Believer religious pictures as an independent symbol.“[17] Old Believer churches would include paintings of demons, unaccompanied by any saintly figures, framed and hanging from the wall. Their purpose was to remind believers of the approaching Eschaton and the vengeance of the Last Judgment, or in Tarasov’s words, “to put the conscience yet more on its guard.”[18]

There is no evidence that Gogol himself was somehow a furtive Old Believer, and this study does not attempt to suggest as much. To the contrary, his personal commitment to the causes of “Orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationalism”[19] makes any strong relationship between Gogol and the Old Believer sect extremely unlikely. Yet while the Old Believer communities were often set apart in Russian society by their “worship and customs regarding diet and dress,” Robert Crummey notes, “The image that Old Believer high culture was hermetically sealed from the outside world… can no longer be maintained.”[20] Tarasov, through examining “New Ritualist” polemics against the Old Believers, concludes that “the ‘new faith’ [regarding icons in particular] was not very easily established in the popular consciousness.”[21] We know at the very least that Gogol was interested in and familiar with some Old Believer literature,[22] for in 1837 Gogol asked his friend Prokopovich to “send him copies of the Nestor and Kiev Chronicles, as well as any recent material on the Raskol’niki [Old Believer] sect.”[23]

Similar religious literature became extremely important to Gogol by the 1840s, as he came to see his writing as “an extension of religious life”[24] and believed moreover that his growth as an artist was dependent on his spiritual growth.[25] In 1842, for instance, Gogol declared in a letter that he desired to study the Bible,[26] and in 1844 he sent his close friends copies (much to their displeasure) of The Imitation of Christ, written by the fifteenth-century French monastic Thomas à Kempis.[27] Chizhevsky has also identified the influence on Gogol of the Philokalia, a collection of Christian spiritual texts by the Eastern Church Fathers.[28]

The iconographic qualities of the portrait of the moneylender suggest a remarkable connection between Gogol’s “central question” of “the ambiguous power of the artistic image itself”[29] and a religious anxiety over the icon that is closely tied to Old Believer devotion. The portrait of the moneylender is an evil iteration of a Rublyov icon, the holiest icons of Old Believer worship, set loose upon the world. It is an exemplar of the very type of painted image that caused the greatest anxiety amongst the devout across Russia, and amongst the Old Believers in particular. To argue for such an eminently religious, even theological concern played out in “The Portrait” is, to be sure, not without precedent. The Slavist Dmitry Chizhevsky, looking over the field of Gogolian scholarship in 1938, declared that:

Students of Gogol (Zenkovsky, Gippius, Mikolayenko) are gradually becoming aware of the fundamental role that religious problems, problems raised in the writings of the Church Fathers – the “spiritual deed,” the heroic feat of “spiritual struggle” – played in the themes of Gogol’s fictional work.[30]

My contention is that the religious problems posed by iconography, particularly within the context of the Orthodox schism, should be added to his list.

Works Cited

Bigham, Steven. The Image of God the Father: Orthodox Theology and Iconography and Other Studies. Torrance: Oakwood Publications, 1995.

Chizhevsky, Dmitry. “About the ‘Overcoat’.” In Gogol from the Twentieth Century: Eleven Essays, edited by Robert A. Maguire, 298-322. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Crummey, Robert O. “Old Belief as Popular Religion: New Approaches.” Slavic Review 52.4 (1993): 700-712.

Gogol, Nikolai. The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York: Vintage Classics, 1999.

Gogol, Nikolai. Letters of Nikolai Gogol. Translated by Carl R. Proffer. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1967.

Jenness, Rosemarie K. Gogol’s Aesthetics Compared to Major Elements of German Romanticism. New York: Peter Lange, 1995.

Maguire, Robert A. Exploring Gogol. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Merezhkovsky, Dmitry. “Gogol and the Devil.” In Gogol from the Twentieth Century: Eleven Essays, edited by Robert A. Maguire, 55-102. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Ouspensky, Leonid and Vladimir Lossky. The Meaning of Icons. Translated by G.E.H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovsky. Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1983.

Tarasov, Oleg. Icon and Devotion: Sacred Spaces in Imperial Russia. Translated by Robin Milner-Gulland. London: Reaktion Books, 2002.

Footnotes

[1] Robert A. Maguire, Exploring Gogol (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), 160.[8] Merezhovsky writes, “The greatest power the Devil possesses [for Gogol] is his capacity to look like something he is not. Though a median, he looks like one of the two extremes or infinites of the world – sometimes the Son made flesh, who rebelled against the Father and the Holy Spirit, who have rebelled against the Son made Flesh. Though a creature, he seems like a creator, though dark, he seems like the dayspring; though inert, he seems winged; though laughable, he seems to be laughing.” See Dmitry Merezhkovsky, “Gogol and the Devil,” in Gogol from the Twentieth Century ed., Robert A. Maguire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 59.

[9] Gogol wrote in a letter to S.T. Askasov on May 16th, 1844, “His [the devil’s] tactics are well known: having seen he can’t incline one to some vile deed, he’ll run away full tilt and then approach from another side, in another guise…” See Nikolai Gogol, Letters of Nikolai Gogol, trans. Carl R. Proffer (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1967), 138

[10] Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, The Meaning of Icons, trans. G.E.H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovsky (Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1983), 27.

[11] Tarasov, 123.

[12] Ibid., 167.

[13] Ibid., 166.

[14] Tarasov, 341

[15] Ibid., 344.

[16] Ibid, 342-4.

[17] Tarasov, 152.

[19] Rosemarie K. Jenness, Gogol’s Aesthetics Compared to Major Elements of German Romanticism (New York: Peter Lange, 1995), 99.

[20] Robert O. Crummey, “Old Belief as Popular Religion: New Approaches,” Slavic Review 52.4 (1993): 708-9.

[21] Tarasov, 141.

[22] Crummey notably writes, “In substantial measure, Old Belief was, in Brian Stock’s phrase, a ‘textual community.’ As I have argued elsewhere, the first Old Believer cultural system was the creation of a group of learned men – a conservative ‘intelligentsia’ if you like – whose rigorously traditional Orthodox Christian views distinguished them from the more cosmopolitan court intellectuals of the late seventeenth century.” See Crummey, 707.

[23] Jenness, 94.

[24] Ibid., 99.

[25] Ibid., 95.

[26] Ibid., 94.

[27] Gogol wrote to his friends Askasov, Pogodin, and Shevyrev, “Devote one hour of your day to concern about yourself; live this hour in an inner life concentrated within yourself. A spiritual book can place you in this condition. I am sending you The Imitation of Christ…“ See Proffer, 134.

[28] Dmitry Chizhevsky, “About the ‘Overcoat’,” in Gogol from the Twentieth Century: Eleven Essays ed. Robert A. Maguire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 314.

[29] Richard Pevear, introduction to The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Vintage Classics, 1999), xix.

[30] Chizhevsky, 314.