hMarat Gelman was born in Chisinau, Moldova on 24 December 1960, the son of Soviet dramatist Alexander Gelman. As a youth, he danced in “Zhok,” a Moldovan folk ensemble, and entered the Moscow Electrotechnical Institute of Communications in 1977, during which time he worked in a number of Moscow Theaters, including the Mayakovsky Theater. He graduated from the Institute in 1983, and upon his return to Chisinau, worked for the next two years as the head of a television factory laboratory. In 1990, he returned to Moscow, and founded the “Gelman Gallery,” one of the first private galleries in the capital, and one which offered “not only…exhibition space, but also…an intellectual workshop, developing ideas and concepts for the art of today’s Russia.” He is best known today not only as a gallery director, but also as an art historian, director of the Center for Contemporary Art, and co-editor of the “Pushkin” journal.

Gelman’s first foray into contemporary art came in 1986, when he occupied the position of director of the Chisinau Scientific and Technical Youth Creativity Center, where he worked for four years. The Center first began to earn money when Gelman launched an exhibition of contemporary art. Despite his lack of experience and knowledge of contemporary art, the exhibition was a success for the Center, and cemented his interest in working in the field of contemporary art.

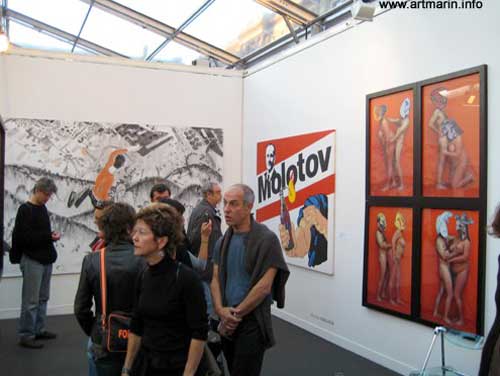

The “Marat and Yulia Gelman Gallery” was founded a year before the collapse of the USSR, and quickly became known not only for showcasing the works of Moscow artists, but also for introducing artistic works from Southern Russia to the capital. The Gelman Gallery showcased then-unknown artists, including the Blue Noses, Avdey Ter-Oganyan and the AES Group. In fact, the gallery was so successful that in the mid-nineties, the right-wing newspaper Zavtra began to refer to all modern artists as “Gelmanoids,” and in 1996, the gallery represented Russia at the first “Art Forum” art fair in Berlin. Gelman does not limit his attentions to art in just Moscow, and in 1998, he organized the “In Search of Cinderella” art festival. The Gallery took the festival to 40 towns across Russia in an effort to introduce the residents of provincial Russian towns to both Muscovite and local artists. In 2001, Gelman signed a deal with the prestigious Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, and transferred 59 pieces to their collection from his gallery. Although it is unlikely that the Museum will showcase a permanent exhibition of contemporary art anytime soon, the Gelman pieces have nevertheless assumed a place in the Museum’s collection.

In 2005, the Gelman Gallery hosted the “Russia-2” exhibit, which showcased works dealing with subjects usually not shown in more mainstream art exhibitions, including Putin, the Kremlin, the Orthodox Church, and Chechnya. The gallery, and in particular “Russia-2,” sought “to create an alternative field for creativity and free thinking,” and the exhibition derived its name from the fact that it portrayed “the other Russia;” namely a Russia inhabited by those who question the status quo. However, showcasing such controversial subjects comes with a price. In 2006, ten ultranationalists stormed the gallery, and forced several employees against a wall before proceeding to tear art off the walls. Gelman himself was hospitalized, although released shortly after with non-serious injuries.

Since 2008, Gelman has worked as the director of the Perm State Museum of Contemporary Art, or PERMM. Most recently, he has opened an art center in that Siberian city, and plans on launching eleven more in cities across Russia. He hopes that, in doing so, he will be able to contribute to a rejuvenation of provincial Russia. However, other attempts at bringing art to cities across Russia has not always been as successful. Earlier in 2012, after hinting at plans to open a contemporary arts center in the city of Krasnodar, Gelman provoked over one hundred residents to take to the streets in an unruly protest when he publicized his exhibition “Icons.” The protest was staged before the exhibition officially opened, and therefore before the works could actually be viewed. The official spokesman for the Russian Orthodox Church later commented:

They showed me the works for the exhibition Icons. Some of the artists are Orthodox believers and certainly not provocateurs. Some are atheists, but even in most of that work, I didn’t see anything particularly anti-Orthodox. There were a few works which seemed controversial to me, but I think it would have been good for the artists to explain what they had in mind when they made the piece. I cannot see anything fundamentally wrong in the exhibition concept.

It is interesting to note that, despite this official statement from the Orthodox Church, the Icons exhibit continues to cause controversy, and its showing in Saint Petersburg was recently canceled after organizers asked Gelman to postpone it until 2013.

Although clearly not adverse to creating controversy, Gelman is also not against protesting controversial artists himself, mostly notably Zurab Tsereteli and his controversial statue of Peter the I which now stands on an artificial island constructed for it in the Moscow river. In 1997, Gelman went so far as to initiate a referendum, which, according to Kommersant-Weekend, brought him “real fame.” However, as the campaign was approaching its peak, Gelman suddenly backed down, and as such, the referendum was never actually held. Shortly after, Gelman received a large space worth about a million dollars from the government, and it was speculated that he had received it for backing away from the referendum. However, both parties denied those claims.

Marat Gelman

Gelman has not limited his attentions to the arts sphere, and has also been involved with politics since 1991. He ran in the 1995 parliamentary elections for the youth bloc known as “The Threshold Generation.” A year later in 1996, he partnered with Gleb Pavlovsky to create the “Foundation for Effective Politics.” In 1999, he ran the headquarters of the liberal “Union of Right Forces” party and during the Moscow mayoralty elections, was the head of candidate Sergei Kirienko’s headquarters. He has also worked as a Kremlin electoral consultant.

Gelman has also found himself involved in politics beyond the official boundaries of the Russian Federation. During Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, both Gelman and Pavlovsky became aligned with outgoing president Leonid Kuchma’s campaign to advise presidential candidate Viktor Yanukovich, and political science professor Gulnaz Sharafutdinova has even gone so far as to call him one of the “key maestros” of Russian spin doctors. He took part in what was known as the “Russian Club,” which provided both financial and logistical support for the campaign. He is quoted as saying at one time: “if Yushchenko becomes president, I will take it as a personal defeat.” However, despite this steadfastness and personal stake, he left the campaign before the elections were held.

Returning to Russia, between 2005 and 2006, he was involved with the Social-Democratic Party of Russia under the leadership of Vladimir Kishenin. In 2010, Putin’s United Russia party launched a new program entitled “Cultural Alliance (regional aspect)” designed to raise the level of cultural awareness in provincial Russia, and Gelman was appointed as the project’s head. However, funding for this endeavor has since been dropped. When recently questioned about his political leanings, Gelman stated, “I do [see myself as a liberal], although I’ve never fought for political power or been part of the opposition. But I always say what I think. I present alternatives without trying to change the whole system. I want to prove that things can work differently.”

Marat Gelman has been an icon on the contemporary Russian arts scene since the fall of Communism. Although he has at times worked with the Kremlin and worked with the pro-Russian candidate in the 2004 Ukrainian election, Gelman makes no secret of his support for the avant-garde and provocative, and this has sometimes cost him. Gelman has helped to spread contemporary Russian art not only outside of Russia, but within it as well, and hopes to open several contemporary art centers across the country. How successful these will be, however, remains to be seen, particularly in light of the recent Krasnodar and Saint Petersburg controversies.