Located in the heart of Old Riga, the Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theater has played a central and outsized role in the history of Russian language arts and culture in Latvia. To this day, about 25% of Latvia’s population is native Russian speaking. This theater, which, in 2023, marks 140 years since its founding, remains an important center for that minority culture.

The Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theater is the oldest Russian professional theater outside of Russia. The theater has changed hands and names, locations and set-ups, occasionally having to close due to wars and other factors. Although the theater today represents a minority culture, its history has long mirrored the history of the Latvian nation as a whole.

The Riga Russian Theater from Its Founding until the Revolution

The history of the theater began on October 2nd, 1883 when a troupe from Pskov was commissioned by the entrepreneurial director and actor Efim Sokolov to come to Riga to perform for a season. Sokolov, a Jew, was better known as E. V. Lavrov, his more Russian sounding stage name and is still referred to by that name in most histories.

His bringing the troupe to Riga came at a fortuitous time. Although the city had been part of the Russian empire for nearly two centuries, it did not yet have a permanent, professional Russian language theater. In the later 1800s, however, the city’s economy was rapidly growing with industrial development. Serfdom had ended and greater social freedoms in Riga were drawing a great number of Russian speaking workers to Riga’s expanding population.

The very first performance of the troupe was given in the hall of the Russian Craft Artel as the troupe did not have a permanent space at the time. Just a few days after the start of the season, however, they moved to the larger Uley Joint-Stock Association Building, which had several performance spaces meant to support the city’s growing cultural scene.

That first season included over 60 performances, beginning with The General’s Wife by Ippolit Shpazhinsky and moving on to many other plays such as Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol, Woe from Wit by Alexander Griboyedov, and translated tragedies by William Shakespeare and Friedrich Schiller.

Known as the Russian City Theater, throughout most the pre-revolutionary period, the troupe was associated with some of Russia’s greatest playwrights and their works. Other major production held in that era included The Snow Maiden by Alexander Ostrovsky, Three Sisters and Uncle Vanya by Anton Chekhov, The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Power of Darkness by Leo Tolstoy, A Month in the Country by Ivan Turgenev, and many more.

In 1902, thanks to the work of another entrepreneurial director and actor, Konstantin Nezlobin, the troupe moved to the newly finished 800-seat Second City Theater (now home to the Latvian National Theater, but originally specifically built for the Riga Russian Theater). Nezlobin also contributed the theater’s development by hiring a number of actors from the Moscow Art Theater, which had risen to world prominence under the leadership of Konstantine Stanislavsky and his revolutionary approach to theater that emphasized achieving realism through newly established concepts in psychology such as emotional memory. Nezlobin fully supported Stanislavsky’s technique and sought to present realism and objective truth on stage.

In 1904, Nezlobin invited his friend Maxim Gorky to come to Riga to help stage his plays there. Gorky was, at the time, on the cutting edge of Russian-language theater and especially theater devoted to showing social problems. Riga at the time was building in revolutionary fervor that would soon explode as one of the major centers of the 1905 and 1917 revolutions.

The Riga Russian Theater after the Revolution

In 1921, after the Latvian War of Independence made Latvia an independent state, the theater received funds from the Latvian government “for the maintenance of theaters of national minorities – German, Jewish, Russian.” During this time period, many renowned artists came to Riga on tour.

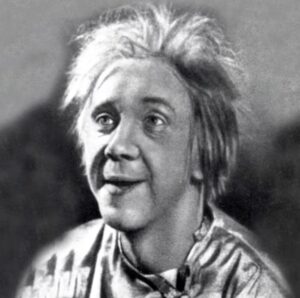

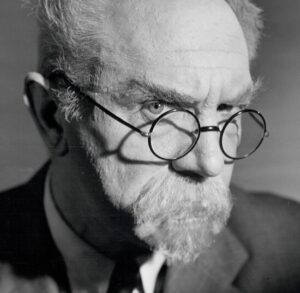

In 1932, Mikhail Chekhov moved to Riga and joined the theater for two seasons. Chekhov was a top student of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theater. He not only performed with the Riga’s Russian City Theater, but also established an acting academy to further Stanislavsky’s System even further, including with the additional insights that he added to that system and for which he is still recognized as one of his generation’s greatest actors and theoreticians.

Many other famous names toured at the theater: Vasily Kachalov, Grigory Khmara, Olga Gzovskaya, Pavel Orlenev, and the director Yuri Yurovsky, who was also involved in the Workers’ Theater in Riga.

In 1940, Latvia lost its status as an independent state as it was taken over by the USSR, ostensibly for “protection” from German ambitions. From 1940 to 1958 the theater was called the State Russian Drama Theater of the Latvian SSR. The theater continued to uphold its artistic ideals, however, and produced a number of innovative productions using the techniques it had come to so strongly rely upon. Among many milestone performances during this time were: West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein, Man of La Mancha by Dale Wasserman, The Caucasian Chalk Circle by Bertolt Brecht, The Lower Depths by Maxim Gorky, The Government Inspector by Nikolai Gogol, The Seagull by Anton Chekhov, and Hamlet by William Shakespeare. A number of famous and well-respected chief and artistic directors worked at the theater over this early Soviet period including Arkady Katz, Leonid Belyavsky, and many others.

One of the only significant periods that the theater closed its doors was during World War II, which was one of the hardest times in Latvia’s long, hard history. Riga changed hands between the Nazis and Soviets and in the process, much of the city was destroyed, its population decimated, and its Jewish community, which had long been a core of Riga’s creative community, was all but wiped out.

In 1958, the theater again changed names. As part of the Khruschev Thaw and in an apparent nod to Latvia’s desire to more independence, the name subtly changed to the State Russian Drama Theater in Riga, dropping any specific mention of the USSR. After Latvia again became independent in 1991, the name did not change. Instead, the “state” part simply came to refer to the newly independent Latvian government rather than the Soviet government in Moscow.

The Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theater in Modern Latvia

In 2006 the theater was renamed to its current title, capitalizing on its former relationship with the great actor, teacher, and thinker Mikhail Chekhov. The theater continues to keep its place and role as a cross-cultural space, coming from a base tradition of Russian theater, but also engaging with a variety of staging directors, designers, actors, and productions from both inside Latvia itself and other countries (Belarus, Estonia, Lithuania, Germany, Sweden, Italy, etc.).

Continuing in this tradition of welcoming broad audiences, many of their main stage productions have subtitles in Latvian and English projected on the wall above the stage. The theater frequently goes on tour and performs in international festivals and competitions. Today the theater puts on a mix of classic plays and new, innovative productions, holding anywhere between five and seven productions, performed in dozens of performances each year.

The Theater’s Historic Location and Building

The current location of the Riga Russian Theater is on Kaļķu iela, meaning “Lime Street”, in reference to the mineral. The street runs through the exact center of Riga’s old medieval center. The name is attested to at least as far back as 1407 and probably arose from the street’s proximity to lime kilns used in construction located on the river’s banks. Sometimes in Russian you will see this name written as “Izvestkovaya Street” (Известковая улица), which is a literal translation of the Latvian name into Russian. The street has borne different names (during the Soviet era, for example, the street was combined with several other nearby roads and was called Lenin Street), but it has long been an important trade hub and site of the ethnic and linguistic diversity present in Riga. Since at least the 17th century, the street has served as a major transportation route into the heart of the city from the river and also has been a significant location for blacksmiths, merchants, and also residential buildings and apartments. Residents from Russia, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, and even further afield have lived here along the same road.

The theater building’s origins lie in an organization of Russian merchants known as the Uley Joint-Stock Association, which was formed in 1863. The main goals of the organization were to support Russian public institutions, the interests of Russian merchants and business, and Russian cultural endeavors in Riga. They were also engaged in various types of educational and charitable work. In 1864, the Uley Association purchased the old post office building and two neighboring buildings on Kaļķu iela. In 1880, they raised over 176 thousand rubles (worth about $2.5 million today) for the construction of a new building on this site. City architect Reinhold Schmaeling was commissioned to design the structure, with the main condition being that the building had a hall for banquets and theatrical performances. The main construction was finished and the building consecrated in 1882.

The façade of the Uley Joint-Stock Association Building seen today is much the same as it was then. It features prominent rustications on the corner of the building and semicircular windows on the third floor which resemble Florentine palazzos, between which there are statues that double as architectural supports. In the cove above these windows there is a reoccurring motif of beehives. This is because “Uley” (улей) means “beehive” or “honeycomb” in Russian. Additionally, this symbol is meant to represent the association and building as a common home of the Russian community and that after a long day of working, they would come to enjoy each other’s company and rest on the building’s premises. The interior of the building is richly decorated with various flutes, motifs, and wood details.

The theater was re-constructed in the 90s. Several details about the original façade and structure of the building were changed and several small courtyards were demolished while a gallery for pedestrians was installed. More recently, the theater was again refurbished and redesigned in 2010 with updated technology. Many of the design “updates” can, in fact, be seen as a return to something closer to the theater’s original look.

Attending the Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theater in 2022

A Review of The Village of Stepanchikovo by Fyodor DostoevskyThe scene is set: a mysterious letter from an uncle far afield, a charlatan pulling the wool over the eyes of a town’s nobles, a love between two characters being pulled apart. These are only a few of the major plot points from a play I saw at the Mikhail Chekov Russian Theater in Riga last fall. The play was named The Village of Stepanchikovo and was an adaptation of the novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky by the same name.

The story follows Sergei Alexandrovich (Сергей Александрович) who is summoned from St. Petersburg to his uncle’s estate in the countryside. His uncle, Colonel Yegor Ilyich Rostanev (Егор Ильич Ростанев), attempts to convince him to marry Nastenka (Настенька), the daughter of a poor provincial official. Sergei finds upon arrival that a middle-aged con-artist named Foma Fomich Opiskin (Фома Фомич Опискин) has the local nobles under his thumb, using trickery and lies to convince them that he’s humble and selfless, when in reality he’s nothing but. Over the course of the play, we see all sorts of shenanigans, comic drama, and romance, all culminating in a marriage and a village made-anew.

Today, The Village of Stepanchikovo, first published in the literary magazine National Annals (Отечественныя записки) in 1859, is one of Dostoevsky’s lesser-known works. However, it has a bit a history behind it. The premier of the stage adaptation of the Village of Stepanchikovo took place in 1891 in Russia. When it was put on by the Moscow Art Theater in 1917, the performance was attended by a then-young Mikhail Chekhov. This fueled his desire to play the antagonist of the show, Foma, a dream he later achieved in 1932 in Riga on the stage of the Russian Theater.

The production I saw in the fall of 2022 lived up to every aspect of the play’s history and demands. The theater company brought the satirical novel about petty tyranny to the stage, breathing life and direction to the work. I was particularly delighted by Anatoly Fechin’s performance as Colonel Yegor. He brought a charming nervousness and humor to the role that made his character one of the most entertaining to watch.

Both the sets and costumes of this adaptation eschewed pure accuracy and recreation for evocation and character development. The result was visually stunning and every choice only heightened the ironies of the characters: full length-skirts and accessories drawn from the 19th century, ill-fitting suits, an eternally worn-bridal veil in stark lights against black backdrops, enormous paintings, or even blocks painted with messages calling for Foma’s downfall. We have the sharp styling and kooky choices made by the costume designer Kristīne Pasternaka to thank for drawing out the idiosyncrasies and eccentricities of each character. The choreographing and blocking of the show was also amazing and original, both of which made the scenes feel taut and lively.

To say that I enjoyed the play is spot on. The play itself ended up being worth more than the sum of its parts: it’s not so often that you get to see a farce in such sharp relief, to see characters bumble over each other in a way that’s both incising and hilarious.

You’ll Also Love

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

How Art Nouveau Became an Expression of Latvian Identity

Latvia’s rich Art Nouveau heritage was shaped by European trends, influenced by local folk aesthetics, and popularized under Latvia’s National Awakening, a movement that first sought to define what it meant to be proudly Latvian. Art Nouveau flourished in Latvia for less than two decades. It rose with the economic prosperity and social mobility at […]

Pauls Stradiņš Museum of the History of Medicine

The Pauls Stradiņš Museum of the History of Medicine, located in Riga, Latvia, is one of the world’s largest museums devoted to healthcare and medicine. It covers the history of medicine from ancient times to the modern, with a special focus on healthcare in Latvia. The museum showcases the historical progression of medical knowledge, instruments, […]

Latvian National Museum of Art

The Latvian National Museum of Art is one of Riga’s oldest and best known art museums. Its permanent collections focus specifically on Latvia’s own national artists and on telling the story of the development of art in Latvia. It also rotates temporary exhibitions that can introduce you to even more striking and more recent Latvian […]

Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theater

Located in the heart of Old Riga, the Mikhail Chekhov Riga Russian Theater has played a central and outsized role in the history of Russian language arts and culture in Latvia. To this day, about 25% of Latvia’s population is native Russian speaking. This theater, which, in 2023, marks 140 years since its founding, remains […]