The Mikhail Frunze Museum in Bishkek was founded by the Soviets as part of their tribute to Mikhail Frunze. Mikhail Frunze was a Red Army leader that was instrumental in crushing resistance in Central Asia during the Russian Civil War. In his honor, the city, which had previously been known as Pishpek, was renamed Frunze in 1926 when Kyrgyzstan became the Kirgiz (Kyrgyz) Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The city changed its name to Bishkek once Kyrgyzstan gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

Below are two experiences at the Frunze Museum that SRAS students have had while on SRAS programs in Bishkek.

Exploring the Frunze Museum

Bishkek hasn’t always been called Bishkek. The city situated in the Chui valley of northern Kyrgyzstan went by the name “Pishpek,” during the 19th and early 20th centuries, and in 1926, its name was changed to “Frunze.” The linguistic jump between Bishkek and Pishpek is not huge – but Pishpek to Frunze?

To give the name change a little bit of context, it’s helpful to know that Mikhail Frunze was an important military leader of the early 20th century and served the USSR as the People’s Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs in 1925. He also happened to be born in the city now known as Bishkek. To learn more about the man significant enough to be the one-time namesake of my current location, I took myself on a little fieldtrip to the Frunze Museum of Bishkek.

I showed up at the museum and thought it was closed. It seemed kind of dark inside, dusty, maybe like they were doing renovations – fortunately a printed sign on the door read “The Museum is OPEN” in Kyrgyz, Russian, and English. After entering and buying a ticket (no student discount without your ID, but if you talk to the attendant long enough she’ll forget about the “Foreign Visitor” price), I made my way up to the third floor and the beginning of the Frunze exhibit.

The third floor is a large collection of late 19th and early 20th century pieces related to war or Frunze’s personal life. The red and white room is shaped like long rectangle, anchored at the back end by a massive stature of Frunze with binoculars and a long military jacket. This floor explains Frunze’s travels in Kyrgyzstan, his influence as a military and political leader, and has an interesting collection of items including cannons, official declarations, and schoolbooks from Frunze’s childhood.

The next stop on your tour of the Frunze Museum is the second floor exhibit, a much smaller room entitled “Frunze and Modernity.” A large portion of this floor is dedicated to pictures of and documents relating to things named after Frunze. You can learn about the Frunze Aviation and Cosmonaut House, or the Frunze Soviet Army House in Moscow. Scattered amongst these artifacts are quotes from speeches given by Lenin and Frunze, presented both in Kyrgyz and in Russian. Flags of various Soviet affiliations hang from the ceiling and there’s even a bust or two of Frunze.

The first floor, the last exhibit hall in the museum, is definitely the coolest. The exhibit is one large room with good use of natural lighting and a ceiling that is about two stories above its floor. This room encases a smaller house, which is claimed to be the actual childhood home of Mikhail Frunze. You can poke around in Frunze’s house and see how a typical home of the intellectual class from the period would be set up. Cool. There aren’t any little plaques or info sheets within the house – it’s presented entirely without comment or explanation, which somehow makes it feel cooler than the rest of the museum. Frunze’s home is the main attraction, which is why visitors are instructed to start on the third floor and make their way down to it, saving the best for last. Outside the house (but still within the house’s first floor exhibition room) is a small, newer exhibit dedicated to Chingiz Aitmatov, a famous figure in Kyrgyz and Russian literature who died in 2008. This exhibit has more information in Kyrgyz than in Russian, and has virtually no English translations.

If you’re planning a trip to Bishkek, the Frunze Museum is worth a visit. Its most expensive ticket price including an English excursion service is 100 som per person (just under two USD) and the quantity and range of things on display are worth a $2 entrance fee. (If you don’t read Kyrgyz or Russian, it’s a good idea to get the English excursion service, as the English translations are limited.) Though a bit shabby in overall presentation, the actual items on display are both interesting and well-kept, as if to emphasize that the point of the museum is remembering history, and not the museum itself. If you’re interested in Soviet history, military history, or just curious about Bishkek’s former name, the Mikhail Frunze Museum is a good place to spend an afternoon.

Olivia Route

A Tour of the Frunze Museum with SRAS

The majority of the Frunze Museum – the top floor and the bottom floor – focus on the military and personal life of Mikhail Frunze. However, the middle floor is a tribute to Kyrgyzstan’s accomplishments, both before and after independence from the Soviet Union.

Visiting the Frunze Museum was a unique experience for the SRAS students studying abroad in Bishkek, since this was the first time that we’ve ever had an exclusively Russian speaking guide. Thus, this doubled as a language lesson. The excursion lasted about an hour and included a lot of language pertaining to war and politics during the Soviet Union.

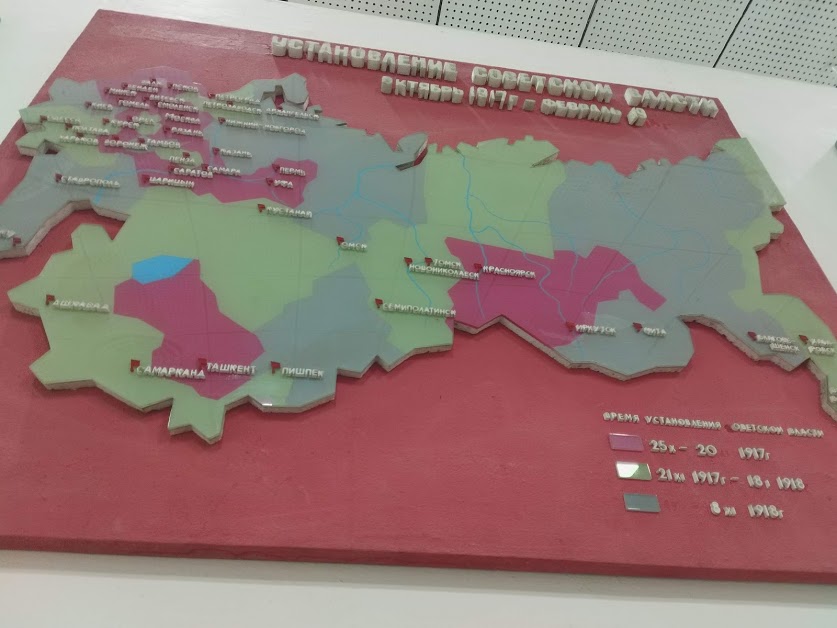

We were first introduced to maps depicting the territory of Bishkek and Central Asia going back to the 1920’s. The purpose of these maps was to show how far Soviet rule had reached in these territories and roughly when it happened.

Since this first section was all about Mikhail Frunze, a larger-than-life statue of him was displayed at the far end of the first floor. Leading up to this point, we were introduced to items from Frunze’s military career and from the Red Army in general. These items included hats, scarves, and weapons – guns and grenades – issued to soldiers of the time. This was accompanied by Soviet propaganda posters, pictures of Frunze at different points during his life and career, a carriage that he had once ridden in, and large and small statues of Frunze.

Finally, our attention was brought to a portion of this top floor, which was a mockup of Frunze’s office. It was lined with pictures from his personal life, including one with his wife and one and only true love, Sofia Popova. This office included a piano since Frunze used to like to play piano and sing during his free time.

We then moved down to the lower level, which was focused on Kyrgyzstan and its developments as a whole, we were introduced to items dating back to the Space Race, spanning to this modern era. My personal favorite portion of this section was the portion on Kyrgyzstan’s contribution to the Soviet Union’s space exploration. A rocket was included in this ensemble, and what I had already learned about some of the pieces, or bolts, for the Soviet’s spaceships being produced in Bishkek, which I had been told by my host dad previously, was confirmed by our guide.

In this section was also a submarine and an army officer’s outfit. Army officers who were Kyrgyz and had served in the Soviet army were also displayed. A bust of one of the commanders in the Red Army, Turdubek Usulbekov, from Kyrgyzstan, was likewise displayed.

We then started moving in to general Kyrgyz items. This included things like komuz or qomuz, an ancient fretless string instrument used in Central Asian Music. There was then a section on Shoro, a Kyrgyz company that manufactures traditional Kygryz drinks: chalap, maksym, and jarma. There were two mini shoro buckets displayed. Then there was a picture of Kyrgyzstan’s coat of arms, which was made following independence. There were also a few pictures commemorating Kyrgyzstan’s development that included pictures of new shopping malls, business offices, entertainment centers, and manufacturing plants. It included Kyrgyzstan’s newest shopping center, Dordoi Plaza, which opened within the last year. This wall was a testament to how far Kyrgyzstan has come since its independence.

After this, we made our way down to the lower level where there is a mockup of the home in which Frunze grew up in. This is probably the biggest highlight of the museum since, according to our guide, it is over 140 years old and the only one like it in the world. It is equipped with original items that were actually in Frunze’s home. It included old books written by Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. We were told that Frunze’s father made his own medicine. There was a section of the house reserved for that. There was a piano in the house that his mom used to like to play, which is where Frunze got his musical talent from.

Once we got to the bedroom, we learned that all of the family members stayed together in one room. The parents slept in the same room as their children. There was a rocking horse (детская качалка) in this room that had been used by Frunze as a youth.

After our tour, our guide asked us where we were from. It turns out that they don’t get many visitors to this museum from America. We were asked to sign our names in a book and leave a brief memo, which all of us did. Despite taking the tour in Russian, rather than English as we usually do on program-organized excursions, I feel that I got a fair amount out of it, and would be curious to go back a second time towards the end of my time in Bishkek to see how much more I could understand.

I personally had never known that the Frunze Museum existed in Bishkek. I would recommend it to anyone traveling the region. It provides a wealth of information about Frunze, about the region, and the life-size, mock-up class house at the end of the tour is definitely a highlight.

Mikaela Peters