Michael Larionov was a major force in several Russian artistic movements of the early twentieth century, most notably the Primitivist, the Cubo-Futurist and the Rayonnist movements. His career went through various stages as he explored and overturned new corners of visual expression and the results shook the foundations of Russian art.

Michael Larionov was born near Odessa in 1881 and spent much of his childhood in the country home of his maternal grandfather, Fyodor Petrovsky. He scraped into Moscow College at the age of 16, achieving the last admitted score on the placement test. He was reportedly a problematic student. Although he displayed an avid work ethic in his own studio, he almost never attended the studios at Moscow College and he even managed to get expelled on more than one occasion. In an infamous display of obstinacy, he once hung at least 150 of his own canvasses at a student exhibition and refused to make room for anyone else’s. The stunt resulted in his temporary expulsion from school. Undeterred, he got expelled again for painting a scandalous depiction of a dancer and a gentleman. He was a year later readmitted, behavior and penchant for semi-pornography unchanged.

Years later, Larionov’s attraction to scandal led naturally to his involvement with the Union of Youth. The group was formed in Saint Petersburg in March of 1910, and became known for its extremely radical public discussions and provocative street antics. They numbered among those Futurists who turned their art into something like street Theater, walking around in colorful waistcoats, radishes and spoons in their buttonholes, the men wearing earrings. From 1912 to 1913, they could be frequently seen in Moscow along the Kuznetskii Most and the Petrovka.

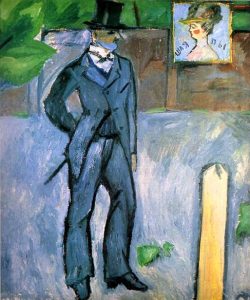

During the Symbolist era in Russian art Larionov briefly joined the Blue Rose movement. His work from this time was markedly more suffused with their pale blues and greens and natural, pelagic themes. When he joined the Union of Youth, this Symbolism got turned on its head, converted into an intentionally harsher, blunter version of the ideology, now brought to the streets for mass consumption. Later he began using bright reds and yellows, derived from an interest in the French Nabis. He also took up their “intimiste” credo, painting personal still-lifes and portraits.

While at Moscow College, Larionov met fellow-artist Natalia Goncharova, who was to be his lifetime companion. In 1906 the two exhibited together at Sergei Diaghilev’s Salon d’Automne in Paris, and in 1914, they went again with Diaghilev to Paris, this time for a lifetime career of stage design. During the interim period, Larionov and Goncharova were together involved in the movements arising in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Some of the most important exhibitions for Larionov’s artistic development were the 1909 Golden Fleece exhibitions and the 1912 Jack (or Knave) of Diamonds exhibitions.

Most works hung at the Golden Fleece were marked by their similarities in style to the contemporary French artists. During his early career, Larionov was known as “the finest Russian Impressionist” (qtd in Gray 102), but his work was really more heavily influenced by Post-Impressionism. In particular, Larionov’s work reflected traits of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and the French Nabis Edouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard. Bonnard and Vuillard were perhaps the most influential overall, known for their use of decorative, brightly colorful motifs and intimate subject matter.

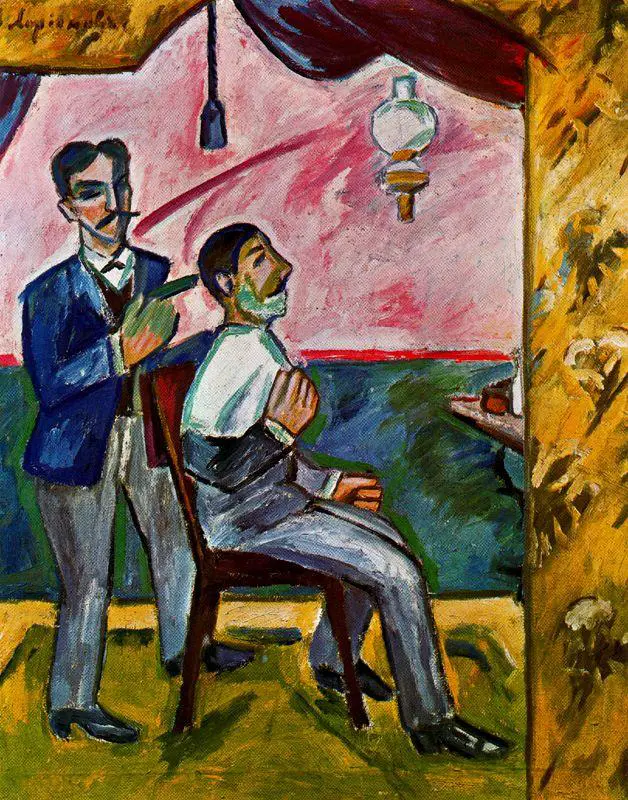

By the third installment of the Golden Fleece exhibits, Larionov’s and Goncharova’s works dominated the space, to the almost complete exclusion of the French artists. Primitivism had taken hold, Larionov and Goncharova together turning their attention from France towards Russian folk traditions. The Primitivist style looked back to peasant art forms, luboks and traditional icon painting for their simplified yet powerful construction. Larionov had been called up for nine months of military service in 1908 and the Soldiers series he painted upon his return was already brimming with patriotic feeling. Perhaps by consequence, Larionov’s interpretation of French Cubism and Post-Impressionism at the Golden Fleece exhibits was looser than Goncharova’s. Rather than using blocks of color and playing with light, Larionov played with the complexity of his figures, isolating their bare elements and arranging them in a way to typify rather than personalize. The more literal, obvious marks of French influence began to fade from his repertoire.

Larionov’s involvement in the Jack of Diamonds exhibitions ultimately led to a rift between the Cubo-Futurists, whom he and Goncharova represented, and the artists of the Munich school. By the time of the second Jack of Diamonds exhibition, Larionov and Goncharova were “so extreme in their nationalist ideas that they had shaken off ‘Munich decadence’ and the ‘cheap Orientalism of the Paris School’” (Gray 122). These dissident Cubo-Futurists splintered into the short-lived Donkey’s Tail group, conceived of as the first purely Russian Russian artistic movement. This and its successor, The Target, were most notable for their connection to a new movement called Rayonnism.

The Rayonnist ideas proposed and executed by Larionov (explored likewise by Goncharova) were pioneering. The theory itself spanned four manifestos. At their heart was a call to do away with objectivity in paintings. Instead of painting empty forms as they seem to appear in nature, Larionov began painting instead the rays emitted by objects. This was an attempt to capture the spaces between viewer and object which were generally missed in visual representation. The rays were meant to connect art to a fourth dimension only intuitively-perceived in our everyday experiences of reality.

In order to create the sensation of a fourth dimension and more fully capture the essence of his subject matter, Larionov gave color and texture supreme importance. He reasoned that color and texture are the only real presences on a canvas, and that consequently they must lie at the heart of the painting’s emotional and spiritual impact. He logically connected the application of paint to the composition of a musical piece, the density of a color, its precise hue and vibrations, adjusting the overall feeling evoked.

In a work entitled Glass (1909) Larionov sought not to depict the image of glass, but its condition and physical composition. With rays, he painted its brittleness, sharpness and sparkling connection to light and sound. In Nocturne (1913-14), Larionov painted the tension between interiors and exteriors with conflicting semi-light and dark rays.

Larionov left Russia with Goncharova in 1914 and turned to Theater design, but his theories had a heavy impact on the coming avant-garde. Rayonnist logic, in particular concerning the fourth dimension, was the jumping off point for many movements in the 1920s. These went on to thoroughly explore the aspects and effects of color, texture and abstract forms.

Source Material From:

The Museum Syndicate, The MoMA, The Guggenheim, The Terminartors, Tate Modern

“Jacks and Tails” by John E. Bowlt in The Journal of the Walters Art Museum, Vol. 60/61 (2002/2003), pp. 15-20.

“The Early Work of Goncharova and Larionov” by Mary Chamot in The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 97, No. 627 (Jun., 1955), pp. 170+172-174.

“Russian ‘Rayism’, the Work and Theory of Mikhail Larionov and Natalya Goncharova 1912- 1914: Ouspensky’s Four-Dimensional Super Race?” by Anthony Parton in Leonardo, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Autumn, 1983), pp. 298-305.