The Nabokov House Museum stands only minutes away from Russia’s famous Saint Isaac’s Cathedral on Bol’shaya Morskaya utlitsa in St Petersburg. The only signs advertising the museum are two small stone cravings that identify the building as Nabokov’s former home. Otherwise, the museum is a hidden literary treasure, available to those that know where to look for it.

The Nabokov House Museum is maintained by the Philology and Arts Department of the St Petersburg State University as an education-oriented project. On the museum’s website, the university asserts that maintaining literary monuments because “the lasting and unchanging quality of Saint-Petersburg rests within its culture.”

Although Nabokov’s family left St Petersburg in 1917, when Nabokov was about 18 years old, he held his former home close to his heart and in high esteem. For example, in his autobiographical novel Speak, Memory he deems it “the only house in the world.” Nabokov meant this literally, as his family constantly moved in Europe and thus did not again establish a home base and Nabokov never returned to his homeland.

Since Nabokov’s family left their St Petersburg home, not much has changed and the interior has been restored and well maintained by the university. Currently, the Green Drawing Room is closed off for restoration.

Since Nabokov’s most popular works of fiction, such as his masterpiece Lolita, were originally written in English and written mostly in the United States, there is a debate in the literary world as to what literary canon he belongs to: Russian or American. The Nabokov House Museum seems to argue that Nabokov and his achievements are firmly to be considered Russian and a solid part of St. Petersburg’s cultural history.

Upon entry into the museum you are transported back into the grandeur of aristocratic life in pre-revolutionary Russia. The only light provided is focused on display cases to highlight the rows of family photos and first edition books written by Nabokov. The room’s walls and ceiling are elaborately wainscoted, a reminder of Nabokov family’s wealth and prominence in Russian society. Although the room is dimly lit, you feel welcomed into the home by Nabokov’s voice as a BBC interview in Nabokov’s native tongue plays on repeat. The effect roots Nabokov to this home and, by extension, to Russia.

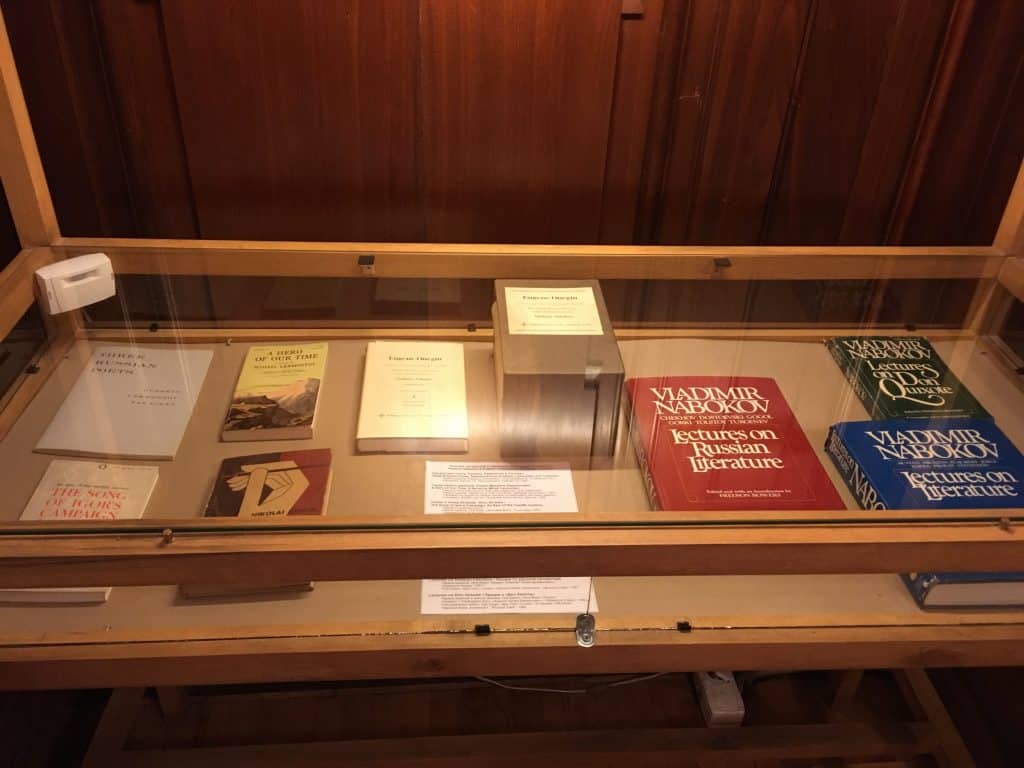

The first published literature you see in the museum is not Lolita, but Nabokov’s English translations of Gogol, Lermontov, Dostoyevsky, and Pushkin. On the other side of this display are various first editions books by Nabokov, including some originally written in Russian such as Invitation to a Beheading (1959), The Gift (1963), The Luzhin Defense (1964). His English novels are also exhibited: Pnin (1957), Pale Fire (1962), Lolita (1967), and The Original of Laura (2009). This display, in providing comparatively heavy weight to his Russian works also contributes to the argument that Nabokov is to be ranked among Russia’s literary giants.

The small museum also places the Nabokov family within Russian history and its major events, including in the resistance to autocratic rule in Russia. In photos, you can see pictures of Nabokov’s father, Vladimir, regally dressed with other politicians. Next to the photos is a write up that details the important history of Vladimir and the Nabokov’s home. Vladimir was part of the Constitutional Democratic Party and his home was used as the final meeting place of the first national congress of zemstvos in November 1904. Photos from this event can be seen on display. At this meeting, the group signed a resolution calling for the creation of a constitution in Russia, which helped precipitate the Revolution of 1905.

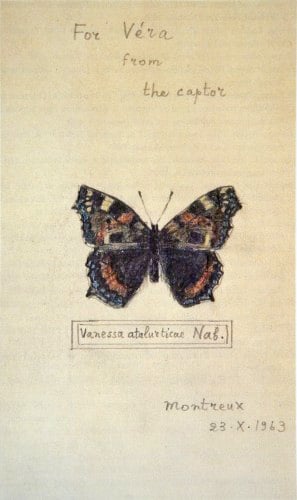

Nabokov is also further humanized with displays showing his other well-known passion for butterfly collecting. His net is on display and insects he collected are displayed throughout the house. Nabokov’s meticulously hand-drawn butterflies take up a whole wall of one room. Some are based on real butterflies, others are created by Nabokov and accompanied by fictitious Latin names. These drawings are deeply personal, as Nabokov was known to gift those closest to him with these drawings. In particular, the wall of drawings mostly shows various butterflies given to his wife of over fifty years, Vera – along with the loving notes that accompanied them.

The room that displays Nabokov’s desk is surrounded by photos of his former homes in Western Europe and the United States also manages to emphasise Nabokov as, in fact, Russian. This room represents a jarring shift in décor from richly Russian to almost severely minimalist, with otherwise bare, white walls. Thus, the focus is on Nabokov and his link to Russia and not with any other national culture.

The museum presents a view of Nabokov that might seem new to most visiting westerners, who know Nabokov mostly as a great English speaking writer. However, as the museum persuasively shows, Nabokov grew to adulthood in Russia and his family was involved in Russian politics and events that would change Russia forever. Nabokov also asserts in his autobiography that he always felt himself rooted in his native culture and language. In fact, in a BBC interview with Duval-Smith and Christopher Burstall, Nabokov said: “my private tragedy, which cannot, indeed, should not, be anybody’s concern, is that I had to abandon my natural language, my natural idiom, my rich, infinitely rich and docile Russian tongue, for a second-rate brand of English.” Nabokov also personally translated many of his popular novels from English to Russian throughout his career, to keep a professional and artistic connection with his homeland.

Nabokov can be considered a rare example of a cultural figure that truly and effectively bridged Russian and English-speaking cultures. Nabokov’s house museum in St. Petersburg presents Nabakov’s strong Russian roots on the Russian side of that bridge.

Nabokov House Museum

47 Bolshaya Morskaya Utlitsa, 190000 St Petersburg

Hours: Tuesday – Friday, 11 to 18. Saturday, 12 to 17. Closed Sunday, Monday, and on National Holidays.

Entry is free.