Soviet underground poetry was not always buried from sight. It had many contributors including those who published both underground and with state publishing houses. The underground scene had an entire ecosystem with not only cutting-edge poems shared between enthusiasts, but also literary journals, underground critics, and even awards ceremonies.

This article highlights five key figures of that world. Though different in voice and approach, each contributed to the underground’s vitality, blending innovation, irony, humor, and global trends into works that reshaped the landscape of late Soviet and post-Soviet poetry. Their collective creativity demonstrates how literature could thrive even in constrained conditions.

Briefly on Soviet Underground Poetry

Soviet underground literature did not always actively oppose the Soviet regime. Much of it was simply written without regard for censorship or ideology. The state-controlled publishing industry prioritized often passed over those works in favor of material that furthered its ideological goals. Many others were never published because they were written with no intention to publish.

Underground writers instead shared texts in the intimate spaces of kvartirniki (apartment readings) and through samizdat (hand-typed manuscripts passed between readers). These underground networks grew into full ecosystems, complete with journals and even literary prizes. The most notable was the Andrei Bely Prize, founded in 1978 by the Leningrad samizdat journal Hours (Chasy), which honored prose, poetry, and criticism that the state ignored. More than an award, it was a symbolic statement that literature could flourish outside Soviet approval.

Some authors found opportunities to publish abroad. This meant having copies of their work surreptitiously taken by someone to an emigre community outside of Russia. These works also often had a political bent as western publishers and emigre publishers often favored authors who directly opposed the Soviet regime. Publishing abroad for Soviet authors could have major consequences for the authors and their families as, if the authorities found the texts to be against Soviet interests, prosecution could follow.

Perestroika, of course, changed all this. As political restrictions fell away, publications abroad soared and publications within the USSR became more common for formerly underground works.

Soviet “underground” literature was therefore not always entirely hidden. In fact, published authors also openly produced material for the underground as well, marking a cross-over between the two worlds. The state did not always target these authors nor was their work always seen as a threat. Yet within this freer space, creativity thrived, producing a remarkable political, social, and artistic phenomenon that merits further study.

Research is complicated by the scarcity of sources, as copies of samizdat have always been scarce and some are now lost. Some digitization efforts are underway such as at the University of Toronto and the Tamizdat Project. Key references include the Oxford Handbook of Soviet Underground Culture in English and the Encyclopedia of Underground Poetry (Энциклопедия андеграундной поэзии) in Russian.

Below, we present profiles of leading figures in the underground literary world. While there are overlaps in method and philosophy of their art, no single individual “invented” the concepts at play. Rather, each contributed to a collective experiment—building, borrowing, and reshaping ideas in ways that reflected their own voice while adding to a broader cultural dialogue.

Yan Satunovsky (1913-1982)

Yan Satunovsky was one of the most quietly radical figures of postwar Russian poetry, a solitary yet deeply influential voice whose work helped shape the underground literary landscape of the late Soviet era. Born in Dnepropetrovsk, to a non-religious Jewish family, he moved through very different worlds: as a young man, he studied chemistry and later fought on the front lines of World War II. While abroad, he wrote extensively, producing a prolific number of stark, acerbic poems about the war that also often reveal a specific, dry humor. Satunovsky seems to have often seen the world as existing despite its banality and absurdity.

He met fellow poet Ilya Ehrenburg while in Prague, who praised his poems and even wrote a letter of introduction for Satunovsky to another poet, Samuil Marshak, although he recognized that the poems could never be published in the USSR.

After the war, he lived in Moscow’s suburbs. His poetry became a touchstone for some of the most important nonconformist writers of the 1960s–80s. His later writings, often critical of Soviet society and haunted by the theme of antisemitism, circulated in literary circles with support from Viktor Shklovsky and Aleksei Kruchenykh, both of whom also had prominent published and unpublished careers. Satunovsky’s poetry would remain unpublished, with the exception of 14 children’s books which did go to press and in which can also be seen his dry, absurdist take on the world and its problems. He had originally tried to have his poetry for adults published abroad, but eventually openly discouraged it, fearing such a publication would put him and his family in danger.

Satunovsky broke with the grand, ideological poetics of his mentors like Ilya Selvinsky, turning instead to the textures of everyday speech. In his breakthrough 1938 poem, “I Asked the Sentry…” (“У часового я спросил…“), he had already rejected the propagandist “given image” of Soviet progress. In it, the DneproGES dam the poem discusses is not a triumph of socialism, but merely “a symbol of reified labor.” Later, in the famous one-liner “I Know That This Is Poetry” (“Я знаю, что это стихи”), Satunovsky provocatively declared a text stripped of all obvious poetic devices outside of a subtle broken rhythm to be poetry. And yet the text is still a beautiful example of its craft.

These works laid the foundation for Russian concrete poetry and the minimalist, conversational style later perfected by the Lianozovo Circle, which was born around Satunovsky. By catching the poetry hidden in stray phrases and official clichés, Satunovsky exposed the emptiness of Soviet language and the loneliness of those who spoke it. His legacy is a radically open poetics that freed Russian verse from ideological “finishedness” — and still resonates in underground and experimental poetry today.

In the post-Soviet era, at least two collections of his work have appeared in Russian: Poems and Prose to Poems (Стихи и проза к стихам) and Do I Wish For Posthumous Fame? (Хочу ли я посмертной славы?).

Read Yan Satunovsky at:

- Rochford Street Review

- Four Way Review

- Yad Vashem

- Vavilon.ru (Original Russian)

- Knigogid.ru (Original Russian)

Elena Shvarts (1948–2010)

Elena Shvarts stands as one of the defining voices of Leningrad’s unofficial poetry scene. Born into a theatrical household—her mother headed the literary department at the Bolshoi Drama Theater—Shvarts immersed herself in literature and culture early, studying philology at Leningrad University and later theater, music, and film. She earned her living translating plays from English and other languages, but poetry remained her true passion. Initially confined largely to samizdat, her first collection appeared abroad in 1985, and four years later a collection of her work, Cardinal Directions (Стороны света), was published in the Soviet Union. In 1993, a collection in English was published, Paradise: Selected Poems.

From her youth, Shvarts was surrounded by fellow poets—Viktor Krivulin, Sergei Stratanovsky, Alexander Mironov, and Vasily Filippov. Yet her voice was distinct. Where Krivulin and Stratanovsky explored the historical crises of the 20th century, Shvarts turned toward existential questions, refracted through the lens of world culture and her own deep sense of Orthodox spirituality.

A self-taught classicist who experimented with Latin, she created inventive “translations” such as Kinfiia (Кинфия), a cycle of poems spoken through the persona of Propertius’ lover Cynthia, where ancient Rome merges with her contemporary Leningrad and with Shvarts’ own unruly voice. Her style was riotous, ironic, and deliberately unconstrained, often embracing masks and personae to escape the banalities of Soviet everyday life. Shvarts won the Andrei Bely Prize in 1979 for poetry.

Shvartz also wrote prose works with much the same freewheeling, rebellious style of colliding imagery and unrestrained language. She wrote a number of short, almost child-like texts throughout the sixties before moving to more sophisticated texts such as the novel in verse The Works and Days of Lavinia (Труды и дни Лавинии), first published abroad in 1987.

During Perestroika, she began publishing officially, traveling abroad, and visiting Rome itself, which remained central to her imagination until her final poems, including her 2009 “Thanksgiving” (“Благодарение“), written as she was dying, where she gave thanks to God for having seen the Eternal City.

Shvarts’ poetry fuses disparate linguistic and cultural layers, its rhythms shifting unpredictably—a legacy of Velimir Khlebnikov’s experiments. However, she is not a pure avant-gardist and merges innovation with tradition. In poems such as “The Dancing David” (“Танцующий Давид“), Shvarts envisions the poet’s role as one of spiritual intensity: “All words have boiled away to salt… throw me like a splinter into God’s fire.” Over decades, she built a coherent aesthetic, weaving together ancient voices, English Romantics, and Russian Futurists into a singular, visionary style.

Shvarts’s influence echoes in poets like Oleg Yuriev, Olga Martynova, and Alla Gorbunova, who inherited her grotesque romanticism and sense of a “disjointed world.”

Read Elena Shvarts at:

- Spectral Lyre

- Poetry Foundation

- Plume Poetry

- Ronnow Poetry

- 45 Parallel (Original Russian)

- Vavilon (Original Russian)

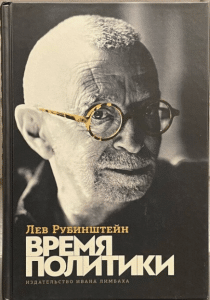

Lev Rubinstein (1947–2024)

Lev Rubinstein was one of the founding figures of Moscow Conceptualism. A graduate of the philology department of the Moscow Pedagogical Institute, he worked for years as a bibliographer in a library, a quiet profession that shaped his view of literature as an archive of voices.

Rubinstein is best known for his “card poems,” a form that began as an almost theatrical performance. Short fragments, sometimes prose, sometimes verse, were written on library catalog cards and read aloud while being shuffled and reordered. When later published, each card retained its numbering, but together they formed a continuous text. This format raised the central Conceptualist question: who is speaking in a poem? In Rubinstein’s work, every new card introduces another voice, a stray memory, or a casual remark. In his poem “Life Is Everywhere” (“Всюду жизнь”), one sequence runs:

“O.K. LET’S BEGIN . . .”

“Life is given to us humans only once.

You be careful, dear, don’t let it slip away…”

“O.K. KEEP ROLLING . . .”

then eventually:

“Here is our endless grief.”

“STOP! FINE. ENOUGH. THAT WILL BE ALL. THANKS.”

This alternating between directive procedural voice and reflective commentary dissolves the poet’s “I” into a choral field of everyday speech and inner dialogue from multiple identities. Rubinstein said of his experimental, surprising, but highly popular method that “it happened to be capable of self-development and evolvement on its own.” He said that the characters in his cards were, in fact, text, which can “come to life, engage in complex interactions with each other, create dramatic tension, die, are reborn, and so forth.”

Though his formal innovations are difficult to imitate directly, Rubinstein’s way of splintering the lyrical voice influenced post-Conceptualist poets of the 1990s like Dmitry Vodennikov and Danila Davydov, and even resonated with political poets of the 2010s—Kirill Medvedev and Roman Osminkin—who used their fractured “I” to explore competing ideologies.

Beyond poetry, Rubenstien was also a journalist, essayist, and perhaps best known for his tireless social activism that involved standing up for nearly any injustice he saw anywhere under the Soviets or modern Russia.

Rubinstein won the Andrei Bely Prize in 1999 and his work has been translated into many European languages. He is known for turning poetry into a critique of speech itself—foreshadowing today’s digital world, where identity is inseparable from the endless streams of information that surround it.

Read Lev Rubinstein at

- World Literature Today

- Medium

- Asymptote Journal

- Poetry Foundation

- 7iskusstv (Original Russian)

- Karta Slov (Original Russian)

Arkadii Dragomoshchenko (1946–2012)

Arkadii Dragomoshchenko’s work was known for questioning Russian literature’s relationship to thought, language, and perception. Born in Potsdam, East Germany and raised in Vinnytsia, in the Ukrainian SSR, he studied philology before moving to Leningrad in 1969 to attend the Theater, Music, and Film Institute. By 1974, his poems circulated in samizdat, and in 1978, he became one of the first laureates of the Andrei Bely Prize.

From the late 1970s, Dragomoshchenko carved out a unique space influenced by a circle of writers, musicians, artists, and philosophers who looked outward to global culture rather than inward to the Silver Age, which had long been a main inspiration of Russian poetry that followed it. In the 1980s, he began a lifelong dialogue with American Language poets such as Lyn Hejinian, Barrett Watten, and Michael Palmer, and later mentored younger Russian poets like Alexander Skidan and Nikita Safonov.

His relationship with Hejinian was particularly deep – the two corresponded frequently and translated each other’s poetry. Particularly after perestroika, his work to integrate Russian language poetry with world trends was tireless. He traveled endlessly and made numerous contacts in dozens of countries.

As critics describe it, Dragomoshchenko’s writing is a logic of ruptures and resonances, where meaning emerges through syntactic disjunctions and sensory echoes. The poet often bypasses rhyme and meter, instead letting thought and sensation structure the poem so rigidly that no external constraints are needed, like in the following untitled poem:

“Grammar doesn’t abide muteness, shards of water,

the incision of a fish, the whooping of birds …

And perhaps that’s good—it’s easier in summer …”

Dragomoshchenko’s influence is vast: he offered an alternative to both Soviet literary orthodoxy and to the Leningrad underground’s nostalgia, showing that poetry could be “a tool of knowledge, sometimes more effective than philosophy or science.” Dragomoshchenko created not just new poems, but a new poetic language—international, open, and endlessly generative for the next generations of Russian poets.

Read Arkadii Dragomoshchenko at

- Bomb Magazine

- Poems and Poetics

- Poetry Project

- Vavilon (Original Russian)

- Gorky Magazine (Original Russian)

Vsevolod Nekrasov (1934–2009)

Vsevolod Nekrasov was a radical minimalist who showed that the raw flow of everyday speech could itself become a complete poetic world. A graduate of the philology faculty at the Moscow Pedagogical Institute, he spent his Soviet years publishing almost exclusively in samizdat. In collaboration with his wife, philologist Anna Zhuravleva, he wrote studies on Russian realist playwright Alexander Ostrovsky, but poetry remained his core pursuit. Only rarely published even after the Soviet collapse as he fiercely disagreed with the cultural policies of major intellectual publishers, Nekrasov nonetheless received the Andrei Bely Prize in 2007.

From his earliest years, he moved among Lianozovo Circle poets such as Igor Kholin, Genrikh Sapgir, and Yan Satunovsky. Later, he was briefly connected to Moscow Conceptualism but broke with it in the 1990s, maintaining close ties only with painters Erik Bulatov and Oleg Vasiliev, who illustrated his late collected works.

Drawing on international concrete poetry, Nekrasov forged a distinctive poetics in which ordinary speech was already poetry—if you knew how to listen. In pieces like “Words are Going” (“Слова идут”), he wrote: “words are going / words are going / and nothing else”—a minimalist declaration that in his work, language is the world, and nothing exists beyond it.

His pared-down, radical voice inspired Russian minimalism (Ivan Akhmetyev) and shaped later poets (Dina Gatina). Nekrasov permanently altered the landscape of Russian poetry, proving that everyday speech could hold and even become the entirety of poetic experience. His major collection in English is I Live I See.

Read Vsevolod Nekrasov at

- Jacket2

- Asymptote

- Vsevolod Nekrasov

- Words Without Borders

- Vavilon (Original Russian)

- HSE University (Original Russian)

You’ll Also Love

Yevgeni Grishkovetz: One Man’s Voice

Yevgeni Grishkovetz is a Russian born novelist, playwright, musician, and actor. He is best known for his theatrical work, particularly with the Theater of Modern Song in Moscow, where many of works have been staged. His writing and performing are known for their insightful nature. He strives to show how experiences are often universal. Often […]

Sergei Lukyanenko: A Psychologist in Russian Science Fiction

In an interview with The New York Review of Science Fiction, Sergei Lukyanenko was asked why he started writing literature, to which he responded: “I couldn’t manage to find the sort of book I wanted to read. So I said to myself, why not simply write the kind of book I want to read? Then […]

Zakhar Prilepin: His Literature and Nationalism

Zakhar Prilepin (Захар Прилепин), born Evgeny Nikolaevich Prilepin in 1975, is an award-winning Russian author, journalist, politician, and activist from the Ryazan Oblast, which borders the Moscow Region in Russia. He is known for both his strikingly realistic writing as well as for his political activity as a nationalist politician and organizer. Zakhar Prilepin’s Early […]

Nadezhda Khvoshchinskaya – A Forgotten Great of Russian Literature

Nadezhda Khvoshchinskaya became a prolific and widely popular author in early 19th century Russia. Her most famous novels reflect on the stylistic staples of 19th century Russian literature, focusing on women’s issues and other social problems through the lens of realism. Despite her fame and success, Nadezhda Khvoshchinskaya has largely been forgotten in the study […]

Vladimir Sharov: Literature That Shines a Light on Dark History

Vladimir Sharov was a Russian writer who was deeply interested in the legacy of Russia’s Communist history. His nine novels focus on various aspects of this history: the communist schisms, Bolshevism, Stalin’s Terror, and the USSR’s collapse, and often mixes or juxtaposes ideas from Communism and religion. Russia’s Soviet history was deeply personal to Sharov, […]