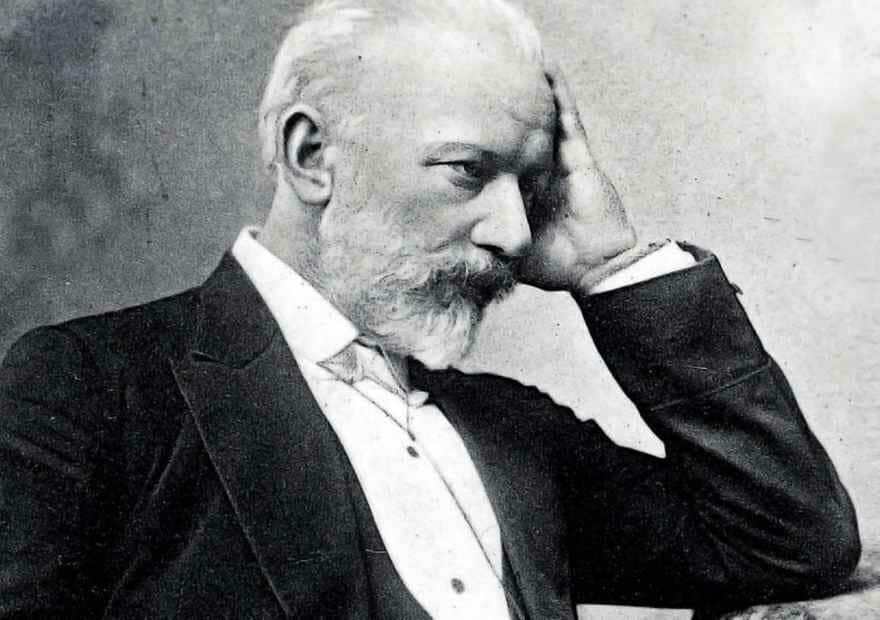

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky is one of the most popular composers of all time and produced numerous symphonies, operas, piano concertos, and ballets. The Russian composer’s works can be found today not only in concert halls across the world, but also used in popular culture as recognizable and emotionally affecting pieces.

Tchaikovsky remains a constant presence in modern Russia, where concerts are regularly given in his honor and where museums serve to educate the public about him and his life. Below are details about how Tchaikovsky is remembered in Russia today.

For more on Tchaikovsky’s life and legacy, see this article on PopKult, our sister site devoted to music and film.

Remembering Tchaikovsky in St. Petersburg

By Jessica Berry (2015)

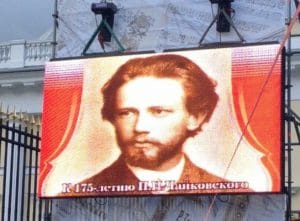

The music of Petr Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) has been very impactful on me since I saw his ballet The Nutcracker when I was a little girl. His music is one of the reasons why I decided to become a Russian musicologist. This year (2015) is the 175th anniversary of his birth and throughout this year, Russia’s musical organizations held concerts celebrating his musical works on what was called the “Day of Russian Music.” I never thought that after only being in St. Petersburg for two days that I would be attending a concert featuring many of the Tchaikovsky’s pieces that I have come to love so dearly.

The concert took place at the Площадь Искусств (Art Square), which also houses the Russian Art Museum. The square also contains a beautiful park where one can go and enjoy the weather of the city. The concert was outdoors and the day was cloudy with light rain, but I was impressed by how many people were in the audience and the majority stayed until the conclusion of the concert. Being a concert that was free and outdoors, the audience was more casual and did not have to adhere to the strict rules of a concert hall. However, this did not take away from the musical experience of seeing an orchestral concert.

The city of St. Petersburg is very important to the music of Tchaikovsky. He began his education here at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in 1850 and when he moved away from a career in law to music, he would be apart of the first graduating class of The St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1865. Many of his most popular works, including the ballets The Sleeping Beauty (1889) and The Nutcracker (1892), the operas The Queen of Spades (1890) and Iolanta (1892), and his Symphony No. 5 (1888) and Symphony No. 6 (1893), had their world premiere in St. Petersburg. This city is also the place where Tchaikovsky died in 1893; his grave is located here in the Alexander Nevsky Cemetery alongside his other musical contemporaries, such as Mily Balakirev, Anton Rubinstein, Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Modest Mussorgsky. For me, there was something very special hearing his music ring throughout the night air of St. Petersburg.

What I really enjoyed about the concert was the variety of music that was performed. Not only were his symphonies and ballet music featured, but also the St. Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra under the direction of S. Kochanovsky performed his violin and piano concertos and arias from his operas with soloist from the opera company at the Mariinsky Theater. I love that the orchestra presented a well-rounded program of his works to show the audience the diversity of his musical style. It was also great to hear such popular works as his Romeo and Juliet, Swan Lake, and Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor. I was super excited when they performed a scene from my favorite Tchaikovsky opera, The Queen of Spades. Even in the cold, rainy night, the audience gave an enthusiastic response after each piece.

I have always been impressed with how the Russians paid tribute to those who created their artistic and literature culture. It was almost a surreal experience being in the audience and I spent a lot of time watching the audience’s reaction to his music. I received warm smiles from older patrons who seemed to be glad that I was enjoying this concert in their city. I also appreciated that some of the friends I made recently through SRAS came along and sat through the concert with me in the cold. They cannot wait to see another concert and I am so excited to introduce to them the beauty of Russian Classical music during my time in St. Petersburg.

Tchaikovsky Museum in Moscow

By Alyssa Yorgan (2014)

The Tchaikovsky Museum, located at 46/54 Kudrinskaya pl. in central Moscow, is part of a complex of museums in Moscow dedicated to Russian musical greats. This network consists of several small “house-museums” (дом-музей) situated in the former residences of luminaries like Sergei Prokofiev, Fydor Shalyapin, and Aleksandr Goldenweiser, with the Glinka Museum of Musical Culture serving as the main point on the tour. While interesting as museums in their own right, many of these locations regularly host concerts that range from intimate chamber-music evenings for an audience of 50 or less, to entire opera presentations (albeit without full staging.) It’s worth checking the main website before making your trip, as prices for concerts vary from free to somewhat pricey (1500 rubles plus). That said, entrance to the museums themselves is always affordable (less than 200 rubles), and there are student discounts.

House-museums tend to be small, as one might guess, and one can usually complete a tour in about an hour. The Tchaikovsky museum staff is really dedicated to helping you make the most of that hour though! In comparison to many other Moscow museums, I find that the staff at the musical culture museums tends to be unusually friendly and informative. It’s clear that they are fans of their respective composers/ performers and this helps to make the experience all that much more enjoyable. It’s likely that you will get a personal tour even without asking for it.

While the flagship Glinka Museum houses most materials of importance to researchers (original musical scores, letters, etc.), the house museums are primarily full of the composers’ personal effects. Wandering from room to room, one gets a sense of what activities and people featured most prominently in the life of that musical figure. In the Tchaikovsky museum, for example, there is a room devoted to one of the composer’s most famous patrons, Nadezhda von Meck. One can get up close to one of Chaikovsky’s pianos, as well as photographs and correspondence from colleagues, friends, and relatives. Many of the descriptive placards are translated into English, making it a good choice for those with no or limited-knowledge of Russian.

In my opinion, the curators have done a good job in making the museum accessible for the novice who has only a passing knowledge of classical music, yet still interesting for those who studied music and want to see artifacts of Chaikovsky’s life up-close. The museum is also located within close proximity to a few other house-museums within the Glinka-complex, making it convenient to do a tour if one so desires.

Tchaikovsky Concert Hall in Moscow: Master Class Performance

By Sarah Parker (2014)

If you’re new to the culture, you’ll soon see that Russians take performance very seriously. Whether it’s orchestra, opera, ballet, or theater, you owe it to yourself to see as many performances as possible, and at least one!

The first stop is the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall (Концертный Зал имени П. И. Чайковского, located at 31/4 Tverskaya St. in central Moscow). It’s easy to find for newcomers to Moscow because it is literally in the same building as the Mayakovskaya Metro Station. Tickets start at 200 rubles, but unlike some venues, even the cheap seats here are great, with an unobstructed view.

I saw the “Master Class” performance. These are students who come to Moscow to study at the prestigious Moscow Philharmonic, under the famous conductor Yuri Simenov. As part of their graduation, they give a concert in this hall. Students are already semi-professional when they enroll as master class students.

This summer’s graduating group came from all over the world: Asia, Scandinavia, South America, Eastern Europe and of course Russia. They all had received multiple awards for their previous work conducting, and had travelled the world with their various projects.

Besides the beautiful music, the theater itself and the philharmonic orchestra are a feast for the eyes. Behind the stage is a modern set of organ pipes, and the room is open and acoustically impressive. We were treated to selections of classical orchestral works by Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, Dvorjak, Stravinsky, Mozart, and Shubert. There were also some newer arrangements of works by Rimsky Korsakov.

In typical dramatic fashion, the most experienced performers and edgy pieces were last, and the build-up was really exciting. The crowd was wild over certain conductors, showing their familiarity with the world of conducting and orchestra. The ability of very young conductors was truly amazing. They led the orchestra through crashing pinnacles followed by pin-drop silence.

While it common for performances in Russia to come with one intermission, this performance had two. During intermissions, guests wander out for coffee and refreshments from little cafes on each floor. The various levels of the theater had different architectural designs, and the third floor resting area is a beautiful place. Afternoon light illuminates stained glass, two stories of classical columns, and a beautiful centerpiece sculpture. A series of bells indicate how much time has passed in the intermission, and you must return to your seat at the third bell! Purchase a program for 100p, it’s always worth it, but not all are available in English. When a crowd really applauds, they begin to applaud in unison, and the performers will continue to bow and receive flower bouquets until the applause stops, but stay to the end to see how each performer, and even the management, receives recognition for their part in the performance.