The World of Art wasn’t just an artistic movement. It was a collection of art critics, painters, sculptors, thespians and clothing designers. It had feet in haute-couture, architecture and book design. It was held together by magazines and exhibitions, connected by powerful and rich benefactors. It believed, as did many movements during the artistic explosion of the 1900s through 1920s in Russia – that the Wanderers of the 19th century, the Realists who had lauded art for a social purpose, had represented an artistic decline.

The movement, sans a manifesto of its precise aims, owed much to its patron, organizer, and public promoter Diaghilev, who in November 1898 had launched the World of Art magazine, and who, from 1899 to 1906, sponsored many important national and international art exhibitions for the group. Some other important promoters were the patron Mamontov and the patroness Princess Mariia Tenisheva, who, respectively, ran the influential artistic communities at Abramtsevo and Talashkino.

The World of Art believed that a credo of art for art’s sake had to be at the heart of all true artistic expression. They specifically distanced themselves from involvement in the sociopolitical realities of the time. Considering art to be more or less a confined, individualized universe of its own, they also espoused a philosophy of artistic self-adulation and individualism. Diaghilev described his generation as follows: “[It] seeks only the personal and believes only in its own cause. This is one of our great qualities.”

As a Symbolist movement, the World of Art sought to allude on canvas and other media to things not present. For the World of Artists, these things not present were pulled from golden ages of the past. They sought shining representations of Russia’s former imperial might and majesty, but the retrospection wasn’t specific to one area or period. The search led to some diverse places including Classical Greece, Ancient Russia, The Palace of Versailles and even the primordial state of man.

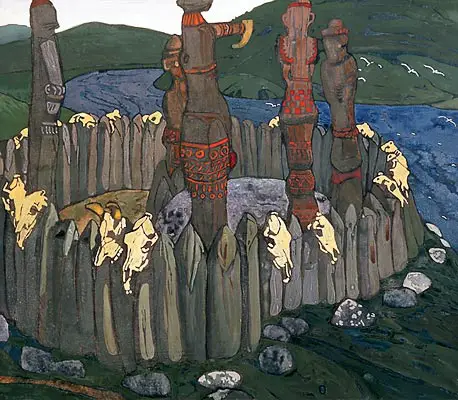

Ancient Russia was a subject depicted primarily by the neo-nationalists Vrubel, Vasnetsov, Roerich, Maliutin and Korovin. Their work was part of a decorative revival which eventually saw the ornate and extremely popular Theater designs of the Ballets Russes.

A large portion of this Symbolist retrospection focused on the 18th century and its traditions of portraiture and landscape paintings. Among World of Art artists, there was a sense that the 19th century had committed something like artistic sacrilege against Catherine the Great’s cultural legacy, in the shift of painterly practice as well as in the neglect of architectural monuments like Mikhailovskii Palace in Saint Petersburg.

Roerich and Vrubel were among those who looked to popular myth and primordial man, painting The Kiss to the Earth (1912) and Demon Cast Down. These works, according to art historian John E. Bowlt “were regarded as embodiments of an archaic and cohesive strength lacking in the disrupted society of pre-Revolutionary Russia.” (172).

A common thread in all this artistic nostalgia was the way its pieces intentionally underlined the perceived decline of the present. Diaghilev’s speech entitled “At the Hour of Reckoning,” made this aspiration explicit:

“Do you not feel that the long gallery of portraits of people great and small… is but a grand and convincing reckoning of a brilliant, but, alas, mortified, period of our history? … We are witnesses to a great historical moment of reckoning and ending in the name of a new, unknown culture,” (177).

The World of Art turned strongly away from the 19th century tradition of Realism in many ways. In particular, aside from the ideological differences already mentioned – the World of Artists shunned the Wanderers for what they saw as a lack of technical finesse and an inattention to stylization. Their own style, in contrast, practically worshiped the line – becoming more and more stylized and decorative. According to Bowlt:

“we find that some of the greatest achievements of the World of Art painters are to be seen in art forms which dictate intensive concentration on line and, in general, require extraordinary concentration and finesse – the miniature, the embroidery, the silhouette, the book illustration, and the diminutive watercolor and pastel” (170).

Printing technologies had improved drastically at the end of the 19th century, and consequently the art of book-design was becoming more sophisticated throughout the reign of the World of Art.

The enterprise of book-making became an outlet for artistic experimentation among many Symbolist artists, in a way similar to the newness and artistic discovery which was appearing in ballet at the same time. Ardently-crafted, ornate book designs became a consuming part of everyday life– and with this came a growing number of rare-book. Artists Benois, Bilibin, Dobuzkhinsky and Somov designed artwork for new additions of old favorites. They worked alongside younger disciples such as Dmitrii Mitrokhin and Sergei Chekhonin.

If the World of Art artists found the new code they were rummaging through ancient myth and the heyday of the imperial admiralty to find, they likely expressed it in one of these two enterprises.

In the World of Art, the visualization of movement became extremely important as an aesthetic device. Many of these painters, with their focus on stylization and their heavy usages of line, made their names by designing costumes for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. These ballets embraced the exotic, the new, and mixed it was the aesthetic extravagance of times past. Among the most fabulous displays of the World of Art concepts put on stage were Bakst’s designs for Cleopatre (1909) and Scheherazade (1910), Benois’ for Petrouchka (1911) and Roerich’s for Le Sacre du Printemps (1913).

Source Material From:

Artnet, Pip at WordPress, Nicholas Roerich Museum, Auburn University, Arcadja

Moscow & St. Petersburg 1900-1920: Art, Life & Culture of the Russian Silver Age, “The World of Art: Sergei Diaghilev and His Circle” by John E. Bowlt. The Vendome Press, 2008.