Russian Symbolism, a diverse literary and intellectual movement at the turn of the 20th century, played a pivotal role in Russia’s adoption of Modernist culture. Inspired in part by the French and Belgian movements of the same name, Russian Symbolism was also a response to the academic moralism and stiff utilitarianism that dominated Russian artistic discourse at the time.

Proponents of Symbolism stressed the importance of beauty and art for its own sake, the value of free individualized expression, the poet as a demiurgic figure, and the approach of a new sublimated era in Russian history.

Russian Literary Symbolism in Context

Russian Symbolism matured at a time when Russian society (like much of Europe) was undergoing a socioeconomic and cultural transformation.

Feudalism had been abolished and as a consequence, the emergence of a new public sphere led to new economies and massive urbanization. Marxism was on the rise in Russia, drawing more attention to workers’ rights and freedoms, while the theme of individualism and the inherent moral worth of every citizen became rallying points among the educated.

For the first time, daily global newspapers acquainted citizens with a vast array of world culture, and significant developments in science and philosophy redefined human experience, inspiring artists toward new forms of expression.

From Henri Bergson’s emphasis on free will and the inner life of the individual to Sigmund Freud’s treatments of the mind’s hidden processes, the context in which Symbolism came to fruition was one in which groundbreaking innovations broke with established norms, and supersensible explanations of reality flourished.

Meanwhile, social Darwinism, which maintained that certain societies were better equipped to persevere than others, became a serviceable model for poets and social philosophers, struggling with a competitive, rapidly changing world.

Much of Russian culture at the time was transfixed by the idea that the old national narrative was coming to an end, and that a new society was imminent. Because late Imperial Russia was burdened by widespread repression, economic collapse, and the costly Russo-Japanese war (1904 – 1905), the mythology of societal decline and rebirth was perhaps felt more palpably in Russian cities than elsewhere in Europe.

Like proper card-carrying modernists, many Symbolists believed that art played a significant role in the construction of Russia’s future destiny.

Early Literary Symbolism in Russia

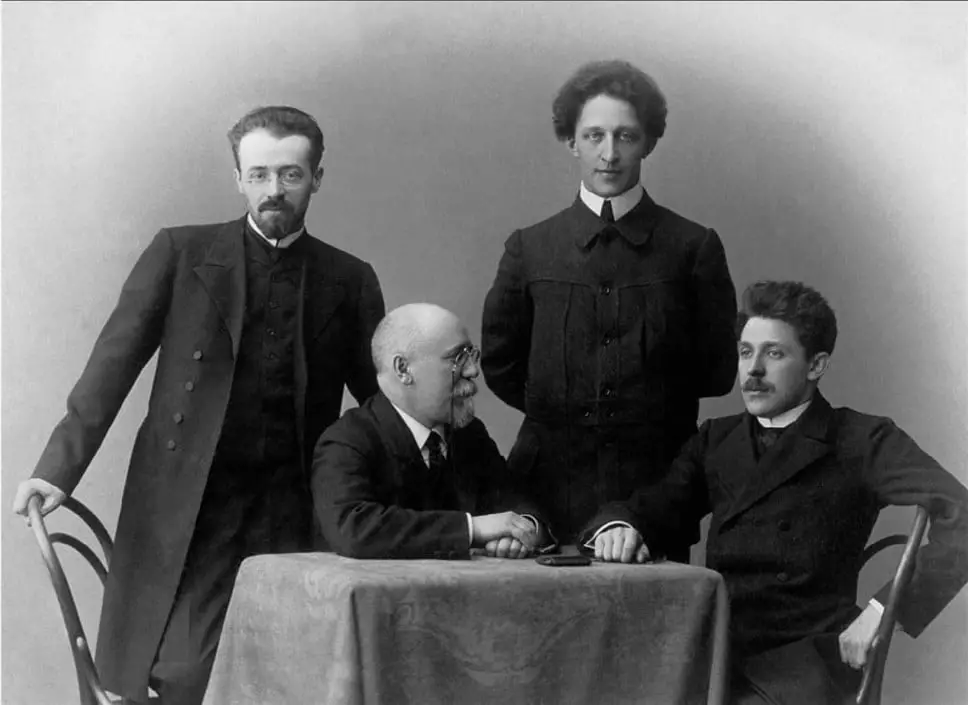

In 1892, the first cogent definition of Russian Symbolism was introduced to the public. In his lecture “On the Causes of the Decline of Contemporary Russian Literature and its New Trends,” Dmitri Merezhkovsky defined the central themes of Symbolism as “mystic content, a use of symbols, and an expansion of artistic sensibility”. One of Merezhkovsky’s chief goals was to reconcile the novelistic legacy of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky with emerging trends in European modernism. Merezhkovsky was largely responding to a lackluster cultural climate in Russia after Dostoyevsky’s death in 1881, when scientific positivism and moral questions about the purpose of art flooded intellectual discourse, alienating the new generation of artists.

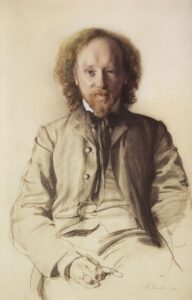

Two years after Merezhkovsky’s lecture, the first of Valery Bryusov’s three-volume anthology Russian Symbolism provided readers with an exemplar of the new style. The edition was exclusively composed of Bryusov’s and a friend’s writing under various pseudonyms, lending to the burgeoning movement more of a solid foundation than it at the time possessed. This was to be a regular tactic of Bryusov, who would soon become a de facto ringleader for the movement.

Not surprisingly, Russian Symbolism quickly added to its ranks.

In 1895, Fyodor Sologub, later known for his magnum opus The Petty Demon, published the first “decadent” novel in Russian, Bad Dreams. Though Sologub became known for his depictions of psychological crisis, cruelty, and malaise, his style bore more resemblance to traditional 19th century Russian prose than that of his fellow Symbolists. Like Bryusov, Sologub became an early organizer for the group, hosting regular Sunday meetings at his apartment on Vasilievsky Island.

By 1900, Konstantin Balmont, a globe-trotting dandy with an ear for rhythmic harmony, had joined the cause, becoming an overnight sensation among culturati. Balmont was Symbolism’s first superstar, a self-taught luminary poet and agile early spokesperson with an astonishingly diverse intellect. He is still revered for his translations of European texts into Russian (he worked in no less than 16 languages!). Though Balmont was not impervious to the gloomy style of his peers, his poetry often evoked a bright optimism as well, as was the case with his wildly popular Let Us Be Like the Sun, published in 1903.

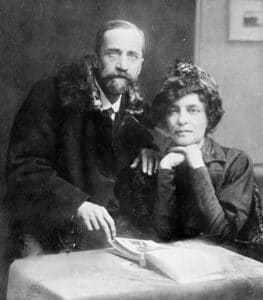

Zinaida Gippius, Merezhkovsky’s wife, was also an important early voice of the movement. Her idiosyncratic and deeply intimate verse capitalized on such decadent motifs as solitude, supernatural evil, and transfiguration through death. Throughout much of her early career, Gippius cultivated the notoriety of a decadent and sexual subversive, however much she tried to distance herself from this calling in later years.

While Gippius is inarguably a more consequential poet than her husband, Merezhkovsky was an intrepid literary and cultural historian with a penchant for Ancient and Renaissance history. Together with Gippius, Merezhkovsky helped set the score for the early days of Symbolism, by founding the Religious-Philosophical Society, a short-lived collaboration between St. Petersburg intellectuals and the Holy Synod of Russia, and running such publications as Novy Put’ (The New Path) and Voprosy Zhizni (Questions of Life).

Though Innokenty Annensky didn’t begin publishing until Symbolism was well underway, he is often roped into this early cadre, due to his arcane, florid language and the impressionistic style of his writing. Annensky was never actively involved with the movement, however, due to his post as a classics teacher in Tsarskoe Selo and his premature death in 1909. Significantly, Annensky’s poetry combines the sheer erudition of Bryusov and Merezhkovsky with the lyrical resonance of Gippius and Balmont.

The “New Phase” of Symbolism

In the first decade of the 20th century, a “new phase” of Symbolism emerged. The first era of Symbolism (roughly 1894 – 1902) was heavily influenced by European decadence, impressionism, and the poetry of Afanasy Fet and Fyodor Tyutchev. Around 1905, however, Symbolist writers began to gravitate more prominently toward Russian mysticism and German idealism.

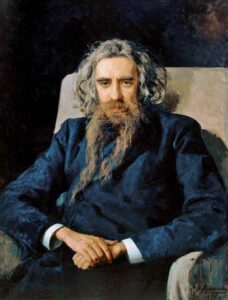

Though Vladimir Solovyov, perhaps the most important Russian philosopher of the late 19th century, had clearly exerted an influence on writers like Merezhkovsky and Gippius, his millenarian worldview became more integral to the Symbolism of the second phase.

Solovyov, whose philosophy was an eccentric blend of Jewish Kabbalah, Christian gnosticism, Hellenistic philosophy, and other mystical strains, predicted that the Apocalypse would soon arrive on Earth. After the so-called “End of History”, a new era would begin under the guidance of Sophia, the Orthodox personification of Divine Wisdom, alternatively referred to by Solovyov as the Eternal Feminine.

Against the background of the tectonic shifts then widely felt in Russian culture, as well as a pervasive anxiety over social degeneration and ongoing revolutionary activity, Solovyov’s vision of earth’s impending transfiguration offered an attractive model for some Symbolists and their audience.

Additionally, with the introduction of a new cast of writers, Symbolism began to evolve from a mostly literary movement into a more articulate canon of literary and philosophical theory. Of the newcomers, Andrei Bely, Alexander Blok, and Vyacheslav Ivanov are doubtless the best known.

Vyacheslav Ivanov was one of the most active theoreticians of the period, in addition to publishing poetry, drama, and translations from Ancient Greek. Ivanov’s work often explored dramatic theory and ancient ritual, as well as German philosophy and Russian eschatology.

One of Ivanov’s frequent theoretical projects was the reconciliation of the Dionysian cult found in Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy with the legacy of Christian mysticism. From 1905 until 1912, Ivanov and his wife Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal (a minor Symbolist poet in her own right) hosted the famous “Wednesday” discussions at their St. Petersburg apartment, colloquially known as The Tower.

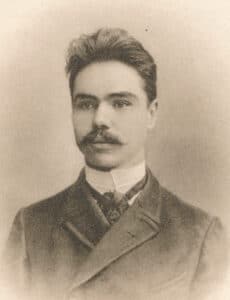

Andrei Bely is most famous for his 1913 novel Petersburg, which many, including Vladimir Nabokov, consider to be the best 20th century Russian novel. Before he became known for his magnum opus, however, Bely was one of the most visible representatives of Symbolism, alongside Bryusov and Ivanov.

In addition to publishing several editions of experimental prose and poetry during the 1900’s, Bely was instrumental in helping formulate the Symbolist theoretical framework. Bely’s 1909 article The Magic of Words, which examines the demiurgic aspects of poetry, has persisted not only as a principal work of Symbolist theory, but also as a prototype for early Futurist poetics. Bely’s worldview was heavily influenced by Solovyov’s conception of the Eternal Feminine, as was also the case with Blok, a childhood friend of Bely as well as a relative of Solovyov.

Like many Symbolists, Alexander Blok was initially inspired by the lyricism of Fet and Balmont, but over time matured into a considerably experimental writer, regularly employing broken rhythmic patterns, unconventional rhyming, and colloquial speech, and incorporating increasingly more reference to urban modernity and the revolutionary spirit of his time.

Blok’s most celebrated poem, and indeed one of his most controversial works, “The Twelve”, portrays Petrograd during the 1917 revolution. Throughout the action of the narrative, large sections of which are represented with racing, idiomatic dialogue, is threaded the image of twelve Red Guard revolutionaries, marching in file through the streets, later identified as Christ’s apostles. To this day, Blok is often considered the second greatest Russian poet among Russians themselves, surpassed in craft and talent only by Aleksander Pushkin.

Symbolism in other Media

At the turn of the century, Symbolism formed ties with the popular arts collective Mir Iskusstva (World of Art). Most prominent Symbolists of the time published poetry and criticism in the group’s highly influential journal. Inspired by the Pre-Raphaelites in England and by Art Nouveau, Mir Iskusstva promoted a return to Romanticism and European aesthetic, and thus joined Symbolism in the protest against the prevailing positivism and social moralism of late-19th century Russia.

Mir Iskusstva’s arts editor and one of their most vocal theoreticians, Alexandre Benois, is often considered a Symbolist because of his cosmopolitan, impressionistic style. Nonetheless, Benois often found himself at odds with Symbolist rhetoric, particularly the revolutionary tendencies of many Symbolists, as well as the movement’s consistent emphasis on individualism.

Painter and mosaicist Mikhail Vrubel might be more aptly considered within the Symbolist context. Vrubel’s work synthesized Byzantine iconography, Russian literary and folk allusion, and post-Impressionist technique, lending to his subjects a metaphorical, transcendental aspect that resisted the social realism popular during the period. Vrubel’s style had a demonstrable impact on the work of Wassily Kandinsky, Pavel Kuznetsov, and others associated with the short-lived but noteworthy Blue Rose art group.

Alexander Scriabin, a controversial composer at the turn of the century, whose work bridges the transition from late Romanticism to modern atonality, is often considered a Symbolist. Not only did Scriabin foster intimate relationships with many Symbolists, especially Ivanov. He is also known for his peculiar brand of metaphysics which drew inspiration from Ivanov’s and Solovyov’s ideas of transfigurative art and utopian communalism.

Russian Symbolism: Ascendancy and Crisis

By 1906, the diligent efforts of Bryusov, Balmont, Bely, and other Symbolist campaigners began to pay off. Under the stewardship of Bryusov, the Symbolist journal Vesy (Scales) had effectively replaced Mir Iskusstva as the leading modernist journal in Russia. Moreover, a host of other journals and anthologies, such as Zolotoye Runo (The Golden Fleece) and Fakely (Torches), helped satisfy demand for the growing trend.

Soon, mainstream publications like Russkaya Mysl (Russian Thought) actively sought contributions from Symbolist writers, and the movement began to acquire its own class of second-rate imitators. Also at this time, prominent Symbolists like Sologub, Balmont, and Gippius released retrospective collections of their work, a sure sign of Symbolism’s established prevalence.

But this success was to be very short-lived.

There had never been (and never would be) a unified vanguard. As the movement became more ideological and began admitting a wider diversity of perspectives, it was only a matter of time before conflicts among its constituents grew glaring and irreconcilable.

Disagreements about the objectives of Symbolism had been mounting for several years when in 1910 a major rupture occurred between two factions. After this “crisis of Symbolism,” as it’s often called, the movement was never able to regain its former significance.

On one side of the dispute was Bryusov, Merezhkovsky, and a dwindling band of supporters, who adopted the old-guard stance that Symbolism was a predominately aesthetic phenomenon.

Meanwhile, Bely, Blok, and Ivanov, claimed that the Symbolist worldview extended to life beyond the confines of art, and imbued the movement with spiritual purpose.

Other factors also led to the fraying of Symbolism: Bryusov’s and the Merezhkovskys’ waning interest in the movement toward the end, the closure of many Symbolist publications after only a few years of operation, a marked shift toward politics after the failed revolution of 1905, and wildly fluctuating personal relations, particularly between Bely and Blok.

Moreover, in 1906, a new strain of Symbolism emerged called Mystical Anarchism, promoted by Ivanov and Georgy Chulkov, editor of Fakely. Main precepts of this new tendency were rejection of the material world, promotion of community among free individuals (what Ivanov called sobornost’), and active resistance of social, religious, and political dogmatism. Though short-lived, Mystical Anarchism led to an early rift among the Symbolists, with important Symbolists like Bryusov and Gippius railing against it.

While many Symbolists continued developing their theories and craft after 1910 (Bryusov and Sologub even contributed to some early Futurist publications), it was clear that the movement now lacked the stamina or unity to survive.

In 1912, a Neo-classicist offshoot of Symbolism called Acmeism took root (albeit briefly). Main contributors to the movement were Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova – often considered the greatest Russian poetess – and her husband, Nikolai Gumilyev. The Acmeists openly advocated poetic craftsmanship, concrete meaning, and clarity of expression, and expended great effort to distance themselves from the decadence and obscurity they perceived in Symbolism.

Nonetheless in practice, Acmeism was frequently indistinguishable from the opaque Symbolist style, belying a deeper connection between the movements than either group would have readily admitted.

Meanwhile, Russian Futurism was rapidly replacing Symbolism as the cultural standard-bearer. In 1912, Hylaea (later known as the Cubo-Futurists) published their famous manifesto, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, in which Symbolists like Balmont, Bryusov, Blok, and Sologub were mocked and explicitly dismissed as relics of the past. The Futurists’ ostensible agenda was wholesale rejection of Russia’s literary past, along with its European influence. The Futurists favored a new literature which would capture the essence of the Russian language and the excitement of the modern era.

Nonetheless, the central avant-garde claim – that Russia was at the dawn of a new era, and that poets were especially capable of helping society navigate toward the future – this claim itself was not new at all, but was partly a reproduction of Symbolist rhetoric.

The Historical Legacy of Russian Symbolism

Much of Russian Symbolism now seems passé. Nevertheless, over its 20 years, the movement proved exceptionably pliable and innovative, unquestionably modern, and in significant ways intrinsically Russian, despite its frequent tendency toward Europeanism. Arguably, Symbolism did as much to modernize Russian culture in the first decade of the 20th century as the early Futurists would do in the second.

Not only did Symbolism cultivate irrefutably exceptional talent – offering up such giants as Aleksander Blok, for example. It also helped create a space in the Russian cultural narrative for the possibility of a new society, at a time when the old one was crumbling to its foundation.

If nothing else, Symbolism can be perceived as a revealing window into an important moment in Russian history, a moment of great transformation and crisis, of concentrated hope and energetic conflict. In the swells and tumults of its own history, Russian Symbolism offers a microcosmic glance on a Russia that was aching to slough off its old rags and exchange them for the fiery ornamental gowns of the future.