Ata-Beyit/Ата-бейит

Day Trip from Bishkek

Ата-бейит (Ata-Beyit, Kyrgyz for “Grave of Our Fathers”) is a memorial complex located in Chong-Tash, a village and skiing destination in the Chui Province about 15 miles south of Bishkek. The site honors two dark episodes in Kyrgyzstan’s history: mass murders that occurred in 1938 at the hands of the NKVD during Stalin’s purges, and the deaths of the revolutionaries who fought in the nation’s 2010 Revolution. Powerful sculptures and monuments pay tribute to those who died in the two conflicts, and a modest museum, shaped like a yurt, covers the political climate in Kyrgyzstan in the 1920s and 1930s, and the Stalin-era repressions.

In 1991, the daughter of a former NKVD officer came forward with a secret her father had told her just before his death. He had witnessed a mass execution at the hands of the NKVD, and this tip eventually led to the discovery of a mass grave in Chong-Tash. In 1938, NKVD officers took 137 (possibly 138) people – members of the intelligentsia including ministers and scientists, and representing 20 nationalities – from a prison in the capital to Chong-Tash, where the prisoners were shot and secretly buried in an underground kiln once used for making bricks.

After their discovery, the remains of the victims were exhumed and moved to a formal, shared grave about 100 meters away. This grave, in the center of a square beside the museum, lies beneath a horizontal sculpture of a тундук (“tunduk”) – the crucial circular piece at the apex of a yurt. The sculpture rests on a large, stone platform, the sides of which are inscribed with all the victims’ names. Stone reliefs along the stairway down to the square from the road above depict suffering at the hands of uniformed men. The kiln where the remains were found can be viewed across the road from Ata-Beyit, behind a glass partition.

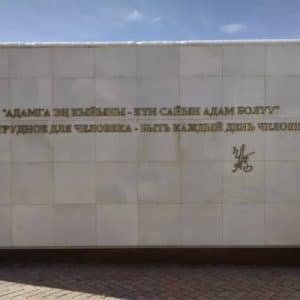

The 1938 execution is the largest known to have occurred in Kyrgyzstan during Stalin’s anti-nationalist purges. One of the men killed in Chong-Tash was Torokul Aitmatov, a politician and father of Chinghiz Aitmatov, a writer and diplomat who is Kyrgyzstan’s most famous literary figure. Chinghiz Aitmatov helped found the cemetery in Chong-Tash, and after his death in 2008, he was buried there as well. His remains lie beneath a memorial of their own, in front of a white stone gate along the far edge of the square. One side of the gate is inscribed with a quote of Aitmatov’s: “Самое трудное для человека – быть каждый день человеком” (“The most difficult thing for a person to do is to be a person every day”). The other side features a portrait of the writer. In the middle, an archway frames a sculpture honoring Aitmatov’s novel, Jamila, and a view towards the village, fields, and mountains beyond.

The revolutionaries honored here also have a history of their own. In 2010, Kyrgyzstan experienced its second Revolution in its decade of independence from the Soviet Union. On April 6 and 7, thousands of protesters filled Ala-Too Square and stormed the White House in Bishkek, reacting to economic hardship and government corruption. Battles with police culminated in bullets fired at the crowd, and over 40 protesters were killed. The protests ousted President Kurmanbek Bakiyev (though the Revolution continued, with escalating violence between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks). Most of the victims of the April protests were buried at Ata-Beyit, down the hill from the museum and the square in a graveyard of their own. They lie beneath individual granite stones inscribed with the names and images of the (mostly young) men. A wall beside the graves lists the names of all who were killed.

Ata-Beyit is not a popular destination for locals. Many of the people I asked in Bishkek had never been there, and those who had visited the site remembered it from a single trip long ago, perhaps with a school group. Our group encountered only two or three other people on the chilly morning we visited. The memorial’s visitors are mostly tourists to the area and relatives of the deceased. It appeared beautifully maintained, however, as well as beautifully designed. It is a powerful celebration of those who have died here at the hands of abusive power, and a glimpse into history both long-buried and fresh.