No other Russian poet of the 90s stands out like Boris Ryzhii. He received some of Russia’s highest literary honors, including honorable mention for the Anti-Booker Prize, and, after his early death, the Northern Palmyra. Composed amidst the chaos and crime of perestroika, his poems stand like opponents in a boxing ring, where ugliness and beauty combat one another, as do strength and weakness, and life and death.

Origins and Inspirations of Boris Ryzhii

Boris Ryzhii was born in the Ural city of Chelyabinsk on September 8, 1974 to highly educated parents Boris and Margarita. His father was a renowned geophysicist; his mother an epidemiologist. When he was six, the family moved to the Vtorchermet neighborhood of Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg). Though they were members of the intelligentsia, the working class social atmosphere of Ryzhii’s hometown had the most significant impact on his poetry. In his poem “I lived like everyone, in a dream, in a nightmare” (Я жил как все – во сне, в кошмаре) he writes that his muses are “not holy faces, but the faces of thugs, saleswomen” (но не божественные лики,/а лица урок, продавщиц). Instead of looking up to intellectual heroes, the main sources of inspiration for his poems were the laborers, vagrants, and criminals that he grew up with. The 2008 documentary Boris Ryzhy, directed by Aliona van der Horst, explores Ryzhii’s rough background through oral interviews and footage of the industrial neighborhood Vtorchermet. The film is free to watch on van der Horst’s site.

The poems of Boris Ryzhii bristle against the violent backdrop of the nineties. The violence he experienced in his life—both as a bystander and a participant—feature heavily in his poems. At 14, the same time he began to write, he earned the title of youth boxing champion of Sverdlovsk. His childhood friend Sergei Luzhin, interviewed as part of van der Horst’s documentary, remembers the respect Ryzhii had—not for his poetry—but for the punches he could throw. In the poem “There in that flat lived ex-convicts,”[1] (В том доме жили урки) Ryzhii writes about scrappy, schoolyard fights: “…So tender was our friendship/that with a final effort/they’d beat me/into pulp – and I could do it too.” (Так ласково дружили –/и из последних сил/меня изрядно били/и я умело бил.) But as the poem continues, Ryzhii reveals the breadth of this violence, almost like a curse, a sickness that can be caught by anyone at any time: “Today our murdered neighbour/was carried down the stairs./I looked at all the faces/faces full of fear./…And that I am not the murderer – /Is pure coincidence, my friend.” (Убитого соседа по лестнице несли./Я всматривался в лица,/на лицах был испуг./…А что не я убийца –/случайность, милый друг.) The deaths of his friends, and the looming sense of loss in his community, caused him a great deal of survivor’s guilt and shame.

Above: Boris Ryzhii speaks about his upbringing and poetic influences

Ryzhii and members of his generation were situated at a unique time in Russian history. They recall the Soviet era, with baby Lenin pins, light blue school albums, and red Young Pioneer scarves, but the end of their youth aligned perfectly with its fall.

In Aliona van der Horst’s documentary Boris Ryzhy, Ryzhii’s close friend and fellow poet Oleg Dozmorov explains that 1991 marked both their school finals and the end of the nation they had spent their entire childhoods believing in. Many in their age cohort did not go to college, and instead turned to crime. Ryzhii found himself straddling the underworld and the upper echelons of the intelligentsia, spending his time with the petty criminals and gangsters of Sverdlovsk despite his educated background. Although he was likely approached for recruitment by these criminals and gangsters, who famously drew much of their muscle from boxing clubs at the time, his friend in youth, Luzhin, insists that Ryzhii never actually participated in crimes himself, and no records incriminate his underground activity.

Renown and Struggle

In 1991, at the age of seventeen, Ryzhii married his classmate Irina Knyazeva and, following the path set forth by his father, graduated with honors in geophysics from the Ural State Mining University in Sverdlovsk. Two years later, in 1993, Ryzhii and Knyaseva had their first child. It was then, during the early nineties, that his poems began to receive recognition and were published in many prestigious journals, such as Zvezda and Znamya. Still, Ryzhii’s accolades never drew him into the intellectual world of poetry. Even while his poems were being translated and anthologized, he remained a working geophysicist. In the poem “Youth promised me a lot” (Молодость мне много обещалa) he jokes about the impracticalities of being a poet: “…you can’t make a living on it/and you can’t buy flowers for anyone./So I became a mining engineer,/I graduated with distinction” (…что не заработаешь на этом/и цветов не купишь никому./Вот и стал я горным инженером,/получил с отличием диплом.) Still, Ryzhii was a prolific poet in his short lifespan, and continued to write until his death.

Ryzhii wrote often about how he envisioned his own death and the pain of existence, though his poems typically mention eternity and the continual impact of the dead on the living. His mental anguish and the suicidal ideations that follow are always excused with mentions of eternity or purpose, such as in “Late at night on the kitchen balcony”: “…you will see the skies as palms/and remember that your life passes by for a reason./In the black earth underneath aching stars./This is a chance to say goodbye…” (…и поймешь, что жизнь твоя пройдет недаром./В черном мире под печальными звездами. —/То — случайная возможность попрощаться…) Perhaps the most painful poems, and the ones most indicative of his internal suffering, are those about his son. “I’m bringing you Legos from Holland” (Я тебе привезу из Голландии Legо) describes an idyllic father-son relationship in which a happy future is built, using the innocent imagery of a Lego castle. However, in the final lines, the verb forms change to show that the son will be building this future alone instead of with his father.

In 2000, Ryzhii completed graduate school in geophysics at the Russian Academy of Sciences Ural Branch. The same year, he was invited to the Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam, and attended the celebration in the Netherlands, traveling away from his wife and son. This was a high honor and the inspiration for the Legos-themed poem mentioned above. This festival was also one of his final forays into the literary world, as he died by suicide a year later, on May 7th, 2001. He was buried in Sverdlovsk, the city in which he spent his short life, surrounded by his fellow bandits and fallen “soldiers of perestroika” (солдаты перестройки), as he describes his friends in the poem “Acquiring a pan-European sheen”).

Above: Russian rapper Husky reading a sample of the poem “Acquiring A Pan-European Sheen.”

Legacy and Continuing Interest in Boris Rizhii

Few American scholars, filmmakers, and artists have analyzed Ryzhii’s life and work. However, in Russia and Europe, he continues to inspire new generations of post-Soviet youth. His gritty, dark, and honest poems speak to the pain of adolescence which Ryzhii himself never truly outgrew, even as a father, husband, and promising field engineer.

One of the most daring and tender explorations into the poet’s life is the aforementioned documentary Boris Ryzhy. At only an hour long, it introduces the viewer to Ryzhii’s wife, sister, friends, and teenage son. Long shots of Vtorchermet, Ryzhii’s old neighborhood in what is now Ekaterinburg, reveal the impacts of social inequality and heavy industry on its inhabitants. By filming these extended scenes and overlaying the audio of his poems, including readings done by his wife and recordings of the poet himself, van der Horst revives his poems from beyond his headstone. This living piece of art honors Ryzhii’s memory, but also reveals the scarring left by his suicide, and serves to add visual texture to his stark and sparing work.

But Ryzhii’s most memorable form of tribute is Belarusian post-punk band Molchat Doma’s viral song “Sudno (Boris Ryzhii),” whose lyrics are borrowed from the similarly titled poem “Enameled vessel” (Эмалированное судно). The use of synth and new wave elements combined with dreary, Russian vocals are the perfect auditory landscape for Ryzhii’s poetry, and enjoyed widespread TikTok popularity in 2020 during the height of the coronavirus pandemic. In May 2020, the song peaked at no. 1 on Spotify’s U.S. Viral 50 chart, and has been used in hundreds of thousands of TikTok videos.

The popularity of “Sudno (Boris Ryzhii)” and its tendency to be paired with romanticized post-Soviet visuals received heavy criticism online, with commenters both American and Russian decrying those who found the videos appealing. However, the virality of the song and the aesthetic it produced speak to the continued relevance, even necessity, of Boris Ryzhii’s work today. It’s easy to see that global online youth, coming of age amidst political unrest and a deadly pandemic—might find solace in the aesthetic grown from Ryzhii’s dark masterpieces, which demand us to realize that beauty must be found in the grotesque, and life must be found from death.

[1] The translation for this poem was done by Marta Biino for Pushkin House. The rest of the translations quoted in this article were done by the author.

You Might Also Like

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

Four Tales of Horror from Russian Literature

Russian language literature is not best known for tales of horror or the supernatural. However, it does have some striking examples in the genre. The most successful are often short stories and, rather than using shock tactics, use ghosts, monsters, or witches to reflect the guilt or inadequacies of those that they visit. Below, we […]

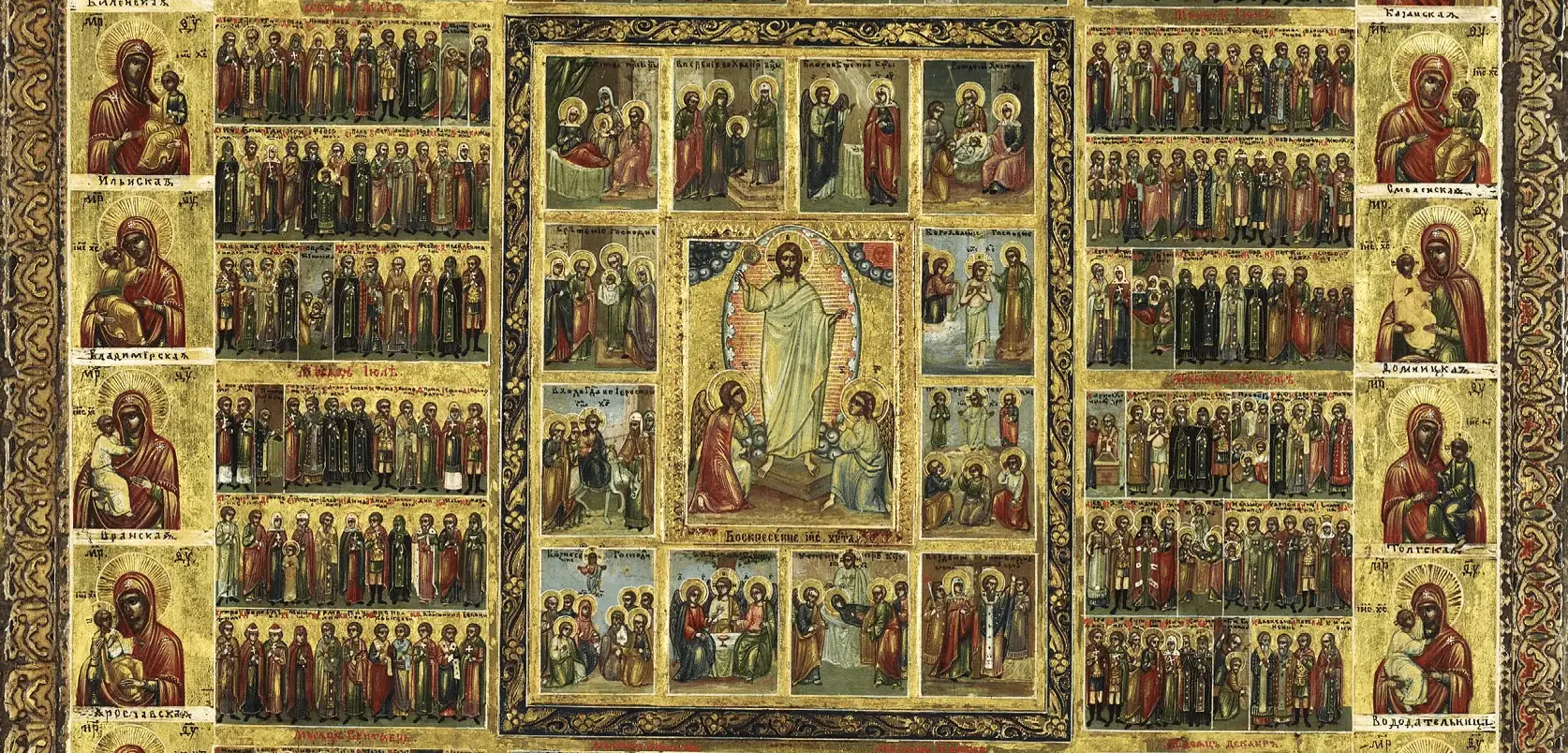

Russian Icons in Detail from The Icon Museum

Russian icons are religious paintings that have been created and used in the Orthodox Christian tradition for centuries. They are an important part of Russian art and culture, and are recognized for their distinctive style and spiritual significance. Icons typically depict religious figures, such as Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints, and are intended […]

Immorality and “General Hypnotism” in Chekhov’s “Gooseberries”

In Anton Chekhov’s short story “Gooseberries,” the societal diagnosis of general hypnotism is developed through carefully manipulated and positioned detail. This general hypnotism is defined as when a person is happy only because they have apparently been blinded to the suffering of others. As the character Nikolay Ivanovitch becomes consumed by his desire for wealth […]

Tretyakov Gallery: A Russian Classic in Moscow

The Tretyakov Art Museum in Moscow houses an extensive and significant collection of Russian fine art, showcasing masterpieces from the 11th to the 20th centuries. The museum provides a deep dive into Russian culture and history through its vast array of paintings, icons, and sculptures, including works by renowned artists like Andrei Rublev, Ilya Repin, […]