Many places in The Master and Margarita, Bulgakov’s cult-classic literary masterpiece, are real places (or based off real places) in Moscow. Furthermore, as Bulgakov lived and died in Moscow, there are many places to visit that are otherwise connected to the author’s life and work. For any Bulgakov fan, a visit to Moscow will not disappoint!

A Tour of the Bulgakov Museum

By Natasha Harwood

Sticking to my roots as a lover of literature and literary museums I had to take advantage of the opportunity to visit the Bulgakov House Museum during my short visit to Moscow. This was one of my must see locations in the Russian capital, and lucky for me I was able to visit the museum as part of an event arranged by SRAS as part of our study abroad program.

Bulgakov’s “Evil Apartment,” or at least the apartment that inspired it, is located at 10 Bolshaya Sadovaya Street, Apt. 50. This is where Bulgakov lived from 1921-1924. The fictional number 302-bis is a cipher of the original building number: 10 = (3+2) x 2. The “bis” part actually means meaning “again” – so in this case, “times two.” The fantastically high number the Sadovaya Streets in Moscow has such a large number) also emphasizes the unreal world of the novel.

The museum itself consists of two former communal apartments located within the same courtyard. One of the apartments is Bulgakov’s former apartment, preserved much as he left it, and the other is the first apartment on the right once you enter the courtyard, which is now a more traditional museum to the artist and his work.

The converted apartment immediately inside the courtyard houses photographs of Bulgakov, his friends and relatives, as well as information on Bulgakov’s life and works. This apartment is rather small, yet cozy, with five rooms connected by a hallway. One of the rooms is dedicated entirely to The Master and Margarita, and another is a café with a modest selection of interesting souvenirs. One of the most interesting features of this part of the museum is in the The Master and Margarita room, in which there is a telephone that can be used to call the devil himself! (or Behemoth, Korovyev, or Azezello).

As for the other part of the museum, Bulgakov’s former apartment is not packed with as much information, and does not take as long to see; however, for me seeing his personal apartment was the best part of the museum experience. The entrance and stairwell leading up to his 4th floor apartment is covered in graffiti—all dedications to the author and his literary works, a tradition that started after Bulgakov’s works were first published in the Soviet Union (in the mid-60s, in censored versions, after his death).

The apartment itself is simple and preserved with a select few artifacts that shed light on the life of Bulgakov. One room has a desk and collection of books that originally belonged to the author. We were allowed to hold the books and see notes made by Bulgakov himself. Then in another room newspapers and journals were on display in which some of Bulgakov’s works were originally published, and in this room you can also see the typewriter Bulgakov used.

After the museum, we visited Patriarch’s Ponds, just around the corner from the Bulgakov Museum, and the scene of one of the most famous scenes from The Master and Margarita, which capped off the experience quite nicely!

Of course I would recommend going to the Bulgakov Museum when in Moscow; however, some of the students on the same tour felt that the museum was interesting, but difficult to fully appreciate if you have not read any of Bulgakov’s writing.

The museum is located in the Tverskaya District of Moscow along Sadovaya Street, and is approximately a 5 minute walk from the Mayakovskaya Metro Station. Both sections of the museum are free to students.

More Scenes from The Master and Margarita

By Sophia Rehm

There are many places in The Master and Margarita that are real places or based on real places in Moscow. Below are a few that can still be seen today.

The Master’s House

The Master’s House is at Mansurovskii Lane, 9.

“‘Ah, that was the golden age!’ whispered the narrator, with shining eyes. ‘An apartment all its own, with a hallway, and a sink with water-’ he emphasized this especially proudly for some reason, “- and a little window just above the pathway that leads from the gate. Across from the window, four steps away and past the fence, were lilac, linden, and maple trees. Ah! In the winter I rarely saw anyone’s black feet in the window or heard the crunch of snow beneath them. And in my little stove a fire was always burning! But all at once spring would arrive, and through the cloudy glass I would see the lilac bushes, first naked and then clothed in green.”

According to his contemporaries, this house once belonged to the Maly Theater stage designer and make-up artist Sergey Topleninov, whom Bulgakov often visited and who was one of the first people to read his novel. “So you described our basement?” his host exclaimed, surprised. “Shh!” smiled Bulgakov, and held a finger to his lips.

It’s hard to believe, but throughout the Soviet era this modest little house in the very center of Moscow remained private property.

The Variety Theater

The Variety Theater is a fictitious theater in The Master and Margarita which is connected, in the structural design of the novel, with imaginary space. In early editions, the Variety Theater was called the Cabaret Theater.

The prototype for the Variety was the Moscow Music Hall, which existed from 1926-1936 and was situated near the Evil Apartment. The Moscow Theater of Satire now stands in its place. Until 1926, this was the location of the Nikitin Brothers Circus – the building was built specially for the circus by the architect Nilus in 1911. The Nikitin Circus is mentioned in Bulgakov’s novel The Heart of a Dog.

Griboyedov’s House

In The Master and Margarita, Griboyedov’s House is the home of MASSOLIT – the huge literary organization, headed by Mikhael Aleksandrovich Berlioz.

With Griboyedov’s House, Bulgakov recreated the House of Herzen, located at 25 Tverskoy Boulevard, which hosted a number of literary organizations in the 20s, such as RAPP (Russian Association of Proletarian Writers), and MAPP (Moscow Association of Proletarian Writers), after which the fictitious MASSOLIT is modeled. This can’t be deduced from the text of The Master and Margarita, but MASSOLIT most likely stands for Socialist Literature Workshop (“Masterskaya sotsiyalicheskoy literatury” in Russian), in the same way that the playwrights’ union of the 1920s, MASTKOMDRAM , stood for Workshop of Communist Drama (“Masterskaya kommunisticheskoy dramy”).

Patriarch Ponds

“One spring day, at the hour of an unusually hot sunset, in Moscow, at Patriarch Ponds, two men appeared.” This scene takes place very close to the Evil Apartment. Patriarch Ponds refers to the ponds on Malaya Bronnaya (during the Soviet era this street was called Pionerskiy Pond). “Ponds” is plural because until the end of the 19th century there were three ponds, which extended to Trekhprudnyi (Three Pond) Lane, which still carries that name.

This is where Berlioz is hit by the tram “turning along the newly-laid line from Yermolayevskiy to Bronnaya…and a round, dark object shot under the railing of Patriarch Path and onto the cobblestone curb. Rolling off the curb, it jumped along the cobblestones of Bronnaya Street. It was the severed head of Berlioz. ”

There is one inaccuracy in the narration, however: judging by the transport scheme of the 1920s, there were no tramways directly next to Patriach Ponds.

Dramlit House

At the end of the alley “her attention was grabbed by the luxurious bulk of an eight-story house, apparently newly built. Margarita flew down and, touching the ground, saw that the façade was faced with black marble, that the doors were wide, that behind their glass the buttons and peaked, gold-braided cap of a porter were visible, and that a gold inscription above the door read “Dramlit House.”

House No. 6 on Vakhtangova Street (which is now called Bolshoi Nikolopeskovsky Lane) is not eight stories, and its façade doesn’t shine with black marble, but this was the building constructed for theater artists in the 1930s. There is also another house, however–almost an exact copy of Bulgakov’s. And its façade is finished with smooth black stone, and apartment 84, where Margarita began to wreak havoc, is on the eighth floor, and the other apartments are even in the right positions and, most importantly, it is a writers’ house. It is located at 17 Lavrushinksiy Lane.

Additional Bulgakov Locations

By Josh Wilson

Moscow Art Theater

The Moscow Art Theater, made famous by Bulgakov’s contemporary, Konstantine Stanislavsky, and his realistic, emotional style of staging plays, is where many of Bulgakov’s works were first staged. Bulgakov and Stanislavsky had a complicated relationship as they worked to bring works to life in an atmosphere of increasing censorship. Today, however, The Master and Margarita and Zoya’s Apartment remain in the theater’s repertoire.

Bulgakov’s Grave

Mikhail Bulgakov is buried in Novodevichi Cemetery, alongside countless other Russian authors, actors, artists, politicians, and other luminaries. Bulgakov’s headstone, a massive granite blob, was actually originally used for Nikolai Gogol, who is buried several paces away. When Bulgakov died of kidney failure at the age of 48, plans were in place to replace Gogol’s tombstone with a bust. Bulgakov adored Gogol and, as a last gift to her husband, Bulgakov’s wife had the headstone re-inscribed and used for her husband. The cemetery is a must-see, no matter what aspect of Russian history or culture you are interested in.

More Articles about Bulgakov on this Site

Mikhail Bulgakov, Master and Margarita, and Truth in the USSR.

Mikhail Bulgakov wrote Master and Margarita between 1928 and 1940, during some of the most severe years of Soviet censorship. During this period authors and poets—the individuals most well equipped to transcend propaganda and recognize societal flaws—were prohibited from doing so at threat of death or imprisonment. However, while direct criticism was impossible, indirect was […]

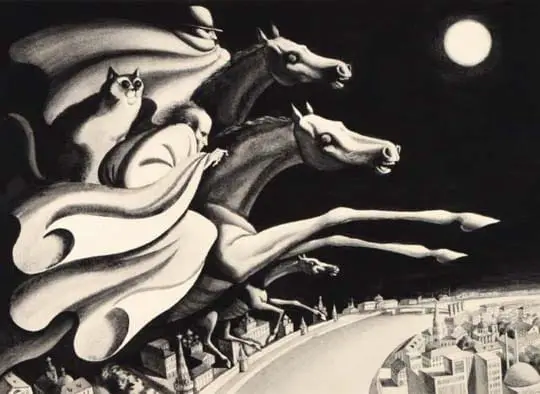

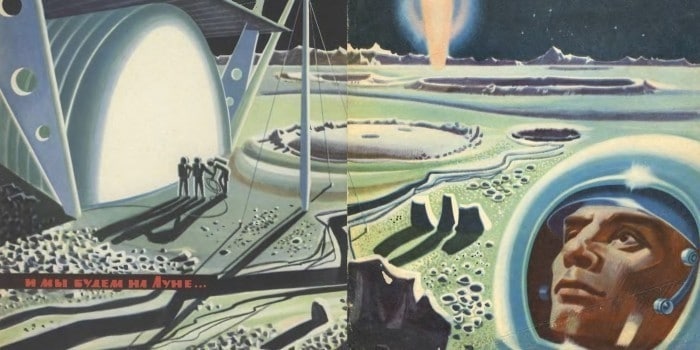

Science Fiction and Fantasy From Behind the Iron Curtain

Science fiction/fantasy, often shorthanded to SFF, is a genre of media concerned with supernatural, fantastical, or other elements beyond our current technological capabilities. Although its roots run deep, borrowing inspiration and elements present in The Odyssey or 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, SFF truly came into its own after the Industrial Revolution. It was a […]

The Control of Semantic Space: Bulgakov’s Challenge of the Stalinist Vision

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (1967) and Heart of a Dog (1925) are among the most provocative works which challenge the Stalinist vision of controlled cultural space. His stories illustrate in detail how space forms society and influences cultural development. Through his prose, Bulgakov exhibits a unique understanding that Stalinism maintained control of society by controlling Soviet space. His […]

‘Irrational’ Rebellions Against Socialist Realism: Czech and Russian Variations on the Legend of Faust

During the 20th century, communist parties assumed state power in Russia and a number of Central and East European countries. The communist leadership of these nations imposed socialist realism as official doctrine governing artistic production. The ruling parties’ ideology emphasized human rationality as the means for creating a well-ordered socialist society, which would be free of […]