The Mariinsky Theater, located in St. Petersburg, Russia, is one of the most iconic and prestigious cultural institutions in the world. Since 1783, it has showcased some of the most famous ballets, operas, and orchestral performances of all time on both its stage and traveling to perform in theaters across the globe upon invitation. In this article, we will explore the fascinating history of the Mariinsky Theater and examine why it remains a respected artistic institution to this day, despite various controversies surrounding new directions and renovations it has undertaken and surrounding statements made by its leadership.

Early History of the Mariinsky Theater

By Max Weber

By the 17th and 18th centuries, opera and ballet had become popular attractions for the Russian elite. With both mediums having originated in Italy, the Russian aristocracy regularly sent their court composers to study under Italian maestros and hired European companies to perform at state events.

As opera and ballet continued to capture the fascination of Russian high society, however, its patrons sought to establish a performing arts infrastructure of their own.

In 1738, Empress Anna Ivanovna ordered the creation of the Russian Ballet School with renowned Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Landé at its head. It was not until the reign of Catherine the Great, however, that opera became an equally enduring fixture in the Russian artistic community. Having herself written several librettos, Catherine II proclaimed in 1793 that “a Russian theater is needed so that it exists not just for comedies and tragedies, but also for operas.” In response, she decreed the creation of a state theater committee to “direct plays and music,” which she staffed with talented Italian composers and performers.

Following this declaration, the Russian government erected a series of magnificent theaters to host Russia’s burgeoning music and performing arts community. The most significant of these were in St. Petersburg.

The first erected was the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater (Большой Каменный Театр, or Big Stone Theater). Designed by Italian architect Antonio Rinaldi, the Bolshoi housed the newly formed Russian Opera and Imperial Ballet Companies, alongside a rotation of Italian and French troupes. As the performing arts continued to gain popularity, two new St. Petersburg theaters – the Circus and Alexandrinsky Theaters – were opened to house the growing Russian circus and dramatic companies, respectively.

By the latter half of the 1800s, the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater mainly served as the performance hall of the Russian Ballet Company. As a result, the Opera was left without a designated facility and forced to share the stages of the Circus and Alexandrinsky Theaters. When a fire destroyed the Circus Theater in 1859, however, the Russian Opera Company again found itself in need of a new home.

From this necessity, the Mariinsky Theater (Мариинский Tеатр) was born.

The Mariinsky’s Early Operatic History

By Max Weber

Named after Empress Maria Alexandrovna, the wife of Tsar Alexander II, the Mariinsky Theater would far surpass the majesty of its predecessors and come to revolutionize the Russian operatic community.

Although opera in Russia had previously been dominated by Italian composers, the Mariinsky, according to Robert Lyall, General Director Emeritus of the New Orleans Opera, was unique in that “the core of its repertoire was truly Russian.” Early productions were based on the source materials of legendary Russian writers and subsequently set by Russian composers.

While later seasons, especially those at the turn of the 20th century, would come to include the works of Western European composers, the Mariinsky’s initial emphasis on Russian artistic might was a harbinger of the central role it would play in Russian performance traditions for centuries to come.

The daunting task of building the Mariinsky fell to Russian-Italian architect Alberto Cavos, who had led renovations on earlier Russian performance halls and was himself the son of Catarino Cavos, a legendary Russian opera composer. Well known for paying close attention to both stylistic and auditory detail, Cavos designed his buildings to be not only visually, but acoustically grand. Describing his previous work on the Bolshoi to Henry Sutherland Edwards, a contemporary British journalist, Cavos stated that the theater “is constructed as a musical instrument” rather than simply a physical structure.

Thus, the Mariinsky had no columns nor a cupola ceiling, opting instead for an acoustically optimal horseshoe shape with a flat ceiling. Striving for intricate visual beauty, he chose to build the new theater in a neoclassical architectural style, while opting for a grand, neo-Byzantine interior which matched Russian imperial styles of the time.

Interestingly, although Cavos constructed many of the Mariinsky’s architectural elements from scratch – including its intricate fringed chandelier, which he himself designed – the building used what was left of the Circus Theater as its base. This was largely at the request of Tsar Alexander II. Enrico Franciolli’s famous ceiling mural, for instance, was repaired and kept as were the Circus Theater’s original façade and stone infrastructure.

The Mariinsky opened in 1860 with a performance of Mikhail Glinka’s nationalist opera A Life for the Tsar, conducted by Konstantin Lyadov. Having premiered at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater in 1836, this opera was – and still is – widely regarded as the first truly Russian opera, as well as the country’s first to be known and performed internationally. Thus began the Mariinsky’s tradition of showcasing Russian works.

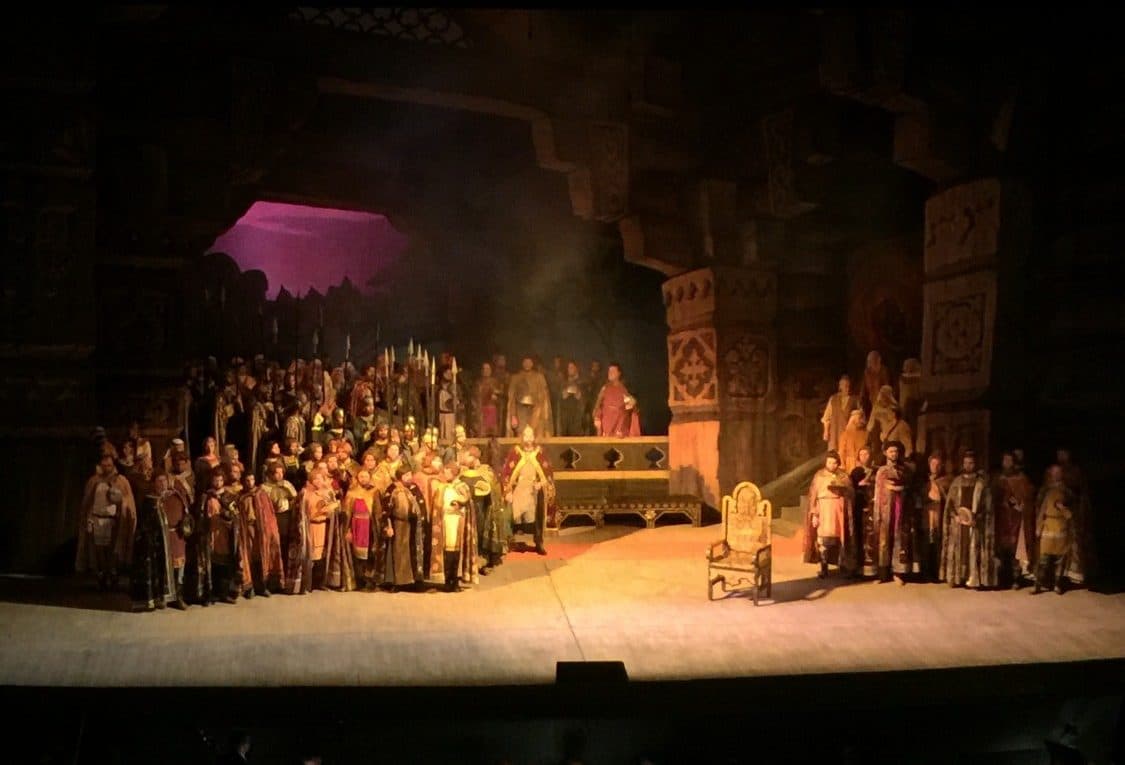

In the half-century following the Mariinsky’s inaugural performance, many of Russia’s most revered operas debuted on its stage. Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov, the most recorded Russian opera in history, made its world premiere in 1874, and the most internationally recognized Russian opera by modern standards, Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades, debuted in 1890. This fifty-year stretch – which the Mariinsky refers to on its official site as a “new, glorious era in [our] history” – occurred under the direction of Eduard Napravnik, who succeeded Lyadov as Principal Conductor in 1863.

Ballet Arrives at the Mariinsky Theater

By Max Weber

Opera was not to be the Mariinsky’s only artistic attraction. By the late 1800s, the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater had fallen into disrepair, no longer suitable for the large-scale performances of its earlier years. In response, Ivan Vzevolozhosky, Director of the Imperial Theaters, transferred Russia’s Imperial Ballet to the Mariinsky in 1885. This transition marked the beginning of Russian Ballet’s “golden age” and ushered a host of legendary ballerinas and ballets into the Mariinsky’s performance hall.

In likely preparation for the arrival of the new troupe and expanded operations, Russian-born architect Viktor Schröter renovated the audience hall in 1884, extending its side wings and audience foyers while replacing the building’s wooden rafters with steel and concrete. Shortly thereafter, in 1885, he added a three-story wing onto the Mariinsky’s left-hand side to accommodate new rehearsal rooms and workshops, as well as modernized logistical facilities. Many of these changes have endured well into the theater’s modern era; the auditorium, for instance, has remained virtually unchanged since its 1884 renovation.

Just as with its operatic playbill, the Mariinsky’s ballet repertoire was marked by a distinctly Russian flair. The debuts of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty (January 3, 1890) and The Nutcracker (December 18, 1892) occurred during this golden age. Furthermore, despite its initial showing at the Bolshoi garnering negative critical reception, the 1895 revival of Swan Lake received international renown after being rechoreographed in part by Marius Petipa, the French director of the Mariinsky’s ballet company.

The Mariinsky Theater and the USSR

By Jasmine Li

On November 9th, 1917, the revolutionary government issued a decree that transferred ownership of the Mariinsky Theater to the state, and its name was changed to the State Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet.

Initially, the move to new ownership and the disappearance of the Tsar’s censors meant that more experimentation was done. In the early 1920s, Sergei Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges, which mixed commedia dell’arte influences with surrealism, and Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier, known for its focus on female leads, were introduced.

In the later 20’s, the question of how ballet could serve the socialist cause became more pressing, especially as the Soviet government began to form a stronger bureaucracy. “Drama-ballets” began to be introduced which emphasized choreographic simplicity in telling modern, socially-relevant stories. Many of these survive in repertoires today and continue to be studied, such as Boris Asafiev’s Flames of Paris or Reinhold Glière’s The Red Poppy.

By the later 30’s, however, all attempts at stylization and experimentation were removed as the Stalinist terror swept the USSR and Socialist Realism was fully implemented as the official genre for all soviet art to follow. “Bourgois” composers such as Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Musorgsky, Verdi, and Bizet began to disappear from the repertoire.

A primary figure of the Mariinsky Ballet during the first half of the Soviet era was Agrippina Vaganova. Vaganova had an already established reputation before the revolution. Afterwards, she was one of ballet’s strongest proponents within the Soviet system and she maintained the teaching methods of the Russian Imperial Ballet at the ballet school of the Mariinsky Theater. Her instruction launched the careers of notable ballet dancers, such as Anna Pavlova, Vaslav Nijinsky, George Balanchine, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. The Mariinsky’s school would be renamed in her honor in 1991 as the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet and continues to be one of the world’s most respected ballet schools.

In 1935, the Mariinsky Ballet changed its name again to the Kirov Ballet, after the assassination of notable Bolshevik revolutionary Sergei Kirov, and would hold this name until the fall of the Soviet Union when the Mariinsky Theater name was restored.

During the Great Patriotic War, the theater was evacuated to the Perm Opera and Ballet Theater, where the artists would spend three winters and two summers, playing thousands of performances at the theater, hospitals, and before military units. After the blockade of Leningrad was lifted in 1944, the troupe returned home, inspiring the creation of the Perm Choreographic School.

During the Cold War, the theater lost several big-name dancers. Some, such as Natalia Makarova, refused to return from the Western countries they visited, while others, such as Galina Ulanova, Marina Semyonova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov were moved to the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. Often, this was presented as a promotion, but often authorities made such transfers to keep politically suspect artists under a more watchful eye.

Starting in the later 50’s, however, political pressure significantly eased. Many of the more classic ballets and composers were rehabilitated and their works found their way back onto the stage.

In 1968-1970, Salomey Gelfer led a major reconstruction effort that rebuilt the main stage, adding a rising floor and adding other technical improvements that aid stage effects and positioning to this day.

In 1988, under perestroika, Valery Gergiev was appointed artistic director and remains there to this day. Gergiev has international connections, groomed a new generation of ballet and operatic stars, and introduced many new operas from Russia and outside of Russia. Under Gergiev, the Mariinsky has claimed its old name and worked itself firmly into the global artistic community.

New Mariinsky Theater Addition Draws Controversy

By Kristin Torres

Even before its official opening on May 2, 2013 the new Mariinsky Theater building was at the center of controversy. The $630 million, 850,000 square feet structure runs the length of an entire block in St. Petersburg’s beloved theater square, nestled behind the original 19th century structure and connected to it by a footbridge. While the staggering cost to the state has drawn ire, it’s the look of the new building that has been at the center of criticism.

St. Petersburg is famous for the intentional and logical planning given it by Peter I, which was at once European, classical, and baroque. With so much intentionality behind the appearance of Russia’s second-largest city and cultural capital, it perhaps should have come as little surprise to the architects at Canadian firm Diamond Schmitt that their vision for the new Mariinsky might be met with naysayers denouncing the structure’s inconsistency with Petersburg’s classical aesthetic.

But that’s par for the course, especially considering that many in Petersburg and Russia in general revere the original theater as a lasting symbol of Russian culture and influence in the artistic world. World-famous for its eponymous ballet company and opera, and having been the place of premieres for some of the most important artists and works in the country’s history – Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker opened here in 1892 – it may be understandable that any proposal to augment or add on to the existing theater would be met with skepticism and strong opinions.

The initial idea to add on to the existing Theater came at the behest of Mariinsky’s artistic director and conductor Valery Gergiev, who wanted to bring the more than 150-year-old Theater into a new era, and to capitalize on modern improvements in technology and acoustics that restricted the original. His wish, however, turned out to not be as easy to realize, as the initial plan for the new building suffered a false start. In the early 2000s, a juried contest was held to select which architects would be chosen to design the new Mariinsky addition, resulting in a win by French architect Dominique Perrault, whose portfolio included designing the French National Library. After beginning construction and pouring millions into his design, the construction was abandoned in 2007 due to unforeseen problems with the planned structure.

After that first unsuccessful attempt to build a new Mariinsky building, the architects at Diamond Schmitt won a second competition and began construction of their vision for the new building. As construction continued, criticisms were raised that the structure looked more like a sports recreation complex or a shopping center, with its limestone and glass exterior and boxy, plain shape. Its clean lines and subdued colors struck many as in contrast to the surrounding examples of neo-classical architecture painted in bright pastels. Many dubbed it “The Mariinsky Shopping Center” for its plain and utilitarian design. An online petition was started, gathering thousands of signatures, to raze the construction before it could even have a chance to be completed.

Jack Diamond, lead architect of the project, told Urban Toronto magazine that the firm had two objectives for its design. The first was to construct a modest, unpretentious building that complemented the original Mariinsky campus without competing with it or overpowering its regal, embellished design. The second objective was to respond to young people, who he says are making up an increasingly large portion of audience demographics at the Theater. “These are young people. They’re vibrant. They’re people on dates,” he said. He also responded to criticism about the exterior of the building in an interview with Radio Free Europe, saying, “People don’t like change. They like their old St. Petersburg, as I do, but I honor it by being modest on the exterior and giving them an opera house that can stand with the rest of the world.”

The interior of the structure includes an amber-colored, backlit onyx wall, which at night radiates through the façade of ceiling-to-floor glass windows and casts a warm glow into the surrounding street. Also inside are a glass staircase, six stages, six rehearsal rooms, and a decidedly traditional horseshoe-shaped, blonde wood auditorium seating 2000 people.

Vladimir Putin attended the star-studded inaugural night, featuring performances by Spanish singer Placido Domingo and leading contemporary ballerinas Uylana Lopatkina and Diana Vishneva. Despite the controversy, Putin praised director Grigoriev for his efforts in bringing the Mariinsky into a new era, saying he “has succeeded not only in preserving the traditions of Russian opera and ballet but has also created the conditions for it to develop.”

Performances will be held in both the new and the old campuses, allowing for more performances and for the Theater to stay open to the public even while constructing and tearing down sets. Previously, during set up and take down, the Theater closed its doors to the public, losing potential revenue and turning away disappointed tourists. The 2013-2014 season opens in August.

The Modern Mariinsky: New Directions and Controversies

By Emma Tkacz

In the post-Soviet era the Mariinsky Theater has retained its prestige, adopting a richer repertoire and establishing more links to international theaters than ever before. In 1992, the theater’s name was restored to the Mariinsky Theater from its previous name in the Soviet era, the Kirov State Academic Theater. Valery Gergiev, who has served as chief conductor since 1988 and in 1996 was named Artistic and General Director, has led all of the major developments at the theater since the 1990s.

Gergiev is one of the most influential figures in classical music and has led tours over Europe, North and South America, China, Japan, and Australia. One of Gergiev’s greatest achievements was a return to performance of operas in their original languages and overall broadening of the theater’s repertoire. The Mariinsky Theater has preserved its historical repertoire, with continued productions of Marius Petipa’s ballets, Glinka’s operas, and of course annual productions of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker ballet. Besides these legacy productions, the Mariinsky stages ballet productions of leading 20th century choreographers like George Balanchine and composers like Igor Stravinsky. Under Gergiev’s initiative, the Mariinsky also began staging Prokofiev’s operas, many of which were banned in the Soviet era. The Mariinsky recruits many of the world’s best performers, such as the well-known Anna Netrebko, a soprano singer who has performed worldwide with the Mariinsky.

In addition to the expansion of the Mariinsky’s repertoire, the theater has undergone several physical changes in recent years. In September 2003, a fire destroyed the Mariinsky’s set workshop. A new concert hall for orchestra performances was built in its place, opening to the public in 2007. It was renovated further in 2009 to add a wing with a restaurant, cafe, music shop, and rehearsal studios. The Mariinsky Concert Hall ranks along the world’s finest concert venues.

The first two decades of the 21st century also saw the opening of satellite stages in North Ossetia and Vladivostok. The Alania Branch in Vladikavkaz in the North Ossetia republic became a part of the Mariinsky Theater in 2017. The Primorsky Branch in Vladivostok, which sits overlooking the Sea of Japan, was built as an extension of the Mariinsky in 2013, and is one of the most modern theaters in Russia.

In 2009, the Mariinsky Theater launched its own record label, working with the London Symphony Orchestra Live for development and distribution of recordings. It showcases orchestra and theater recordings and is available on Apple Music and iTunes.

The Mariinsky Theater has undergone several developments under Valery Gergiev, but its future is quite uncertain. Since the February 24 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky have been sidelined from performances abroad due to the conductor’s close ties with Vladimir Putin. Notably, performances at Milan’s La Scala theater and New York’s Carnegie Hall, with which the Mariinsky previously enjoyed close cooperation, have been canceled. Several operas and orchestras where Gergiev conducted have also severed ties, raising questions of what is to come in the future for the world-renowned St. Petersburg theater.

Watching Don Giovanni at the Mariinsky Theater

By Jacqueline Dufalla, 2013

The Mariinsky Theater has gotten a lot of press lately with the controversial opening of the new Mariinsky stage. Many residents of St. Petersburg have complained that the new Mariinsky stage is hideous and does not fit with the style of the city. Some have suggested that a new façade be added to the new building. Regardless of the controversy, a night at either Mariinsky is a night to remember.

Although it is my dream to see Eugene Onegin / Евгений Онегин performed in Russia, the production had closed for the summer, so I went to see my second favorite opera, Don Giovanni / Дон Жуан. Don Giovanni, composed in 1787 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, follows the story of Don Giovanni, an infamous womanizer. In the beginning, we see that he has taken advantage of a young woman. This woman’s father chases Don Giovanni out of the house and Don Giovanni kills him. The woman’s fiancé then pledges to kill the criminal, although it is still unknown that it is Don Giovanni. Through a series of events, including the attempted seduction of more women, Don Giovanni invites the spirit of the dead father, the “Commendatore,” to dine with him. The next day, the Commendatore arrives at dinner, where Don Giovanni has descended to base debauchery. The Commendatore asks him to repent, and when Don Giovanni refuses, the Commendatore drags him to hell.

I have seen two other productions of Don Giovanni, one in Pittsburgh and one on film, but of course, the Russian version was unique. For instance, since there are many couples in this opera, there was a lot of intimacy on stage, which looked exactly like the type of public displays of affection notable in Russia, such as on the metro, on the street, in the park, et cetera. For instance, in America, when there was a tender moment, the couple might kiss and exit the stage. In this Russian production, there was a lot more kissing and then, in one instance, the man playfully slapped the bottom of the woman before exiting.

The opera also had subtitles, but they were in Russian. I knew the story beforehand and the premise is not very difficult to figure out, so that was not much of a problem. However, the couple next to me was from Spain and only spoke Spanish and English, and did not appreciate the Russian-only subtitles. In comparison to the other productions I’ve seen, the conducting and talent of the singers was impressive and incredibly well done. The set was “modern” with a large cutout of a naked woman, which the Russians to other side of me complained about being in “bad taste” and did not understand why the set was not more traditional. Although sitting on the side of the theater made it sometimes difficult to see, I thought the set was interesting, and of course, the Mariinsky itself was beautiful to observe.

Despite the different opinions, the Mariinsky production of Don Giovanni was well worth the 800r ticket and 30r program. I also saw Anna Karenina / Анна Каренина two years ago, which also took a more modern approach, and was also still an excellent production. Although sometimes productions may be more modern and experimental, the Mariinsky really can boast being one of the best theaters for ballets, operas, and other musical productions.

Attending The Mariinsky Theater Symphony Orchestra in St. Petersburg

By Jessica Berry (2015)

There is nothing I love more than playing in a symphony orchestra. I have performed with an orchestra on the flute, cello, and with a choir. I also enjoy going to concerts where a symphony orchestra is playing. Ever since my dad took me to see the New York Philharmonic as a little girl, I’ve loved symphonic music and make it a point to go to an orchestral concert whenever I can. I was so excited when I bought my ticket to see the Mariinsky Theater Symphony Orchestra because my favorite conductor, Valery Gergiev, would be directing the symphony. Valery Gergiev is the general director and artistic director of the Mariinsky Theater and has conducted leading symphony orchestras around the world, including the London Symphony Orchestra and the Berlin Philharmonic. He has even conducted Russian operas at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. I have been a huge fan of Gergiev since I saw him direct Mikhail Glinka’s opera Ruslan and Lyudmila, which I bought on DVD when I started my Russian musical studies. This would be the first time I would see him conduct in person.

The concert that I attended was to honor the pianist Lucas Debargue who won the prize of the Moscow Music Critics Association at the 15th International Tchaikovsky Competition, which took place in Moscow and St. Petersburg this past summer. This competition began in 1958 and is held every four years. In its present form, pianists, violinists, cellists, and singers perform in front of a jury who grade their musical style and overall musicianship. Valery Gergiev was appointed the competition’s chairman in 2011 and this year he arranged for the entire competition to be aired for free online so that the world could watch these rising stars. The prize that Debargue won is awarded to the pianist whose performance is of genuine musical significance, and whose gift, artistic vision and creative freedom have impressed the critics as well as the audience. Debargue has become a superstar, selling out concert halls wherever he performed and I was glad I was able to see him perform.

The concert took place at the Concert Hall, which is about a five minutes walk from the historic Mariinsky Theater. The pieces that were performed that evening were Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 4 in E flat major, Franz Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major, and Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, Act III. Although I knew The Nutcracker, I had not heard the other two pieces. I truly enjoyed going to an orchestral concert in which I have not heard the music before. When you are familiar with a piece of music, you can be highly critical of the orchestra because you may have a favorite interpretation of a certain piece. When you do not know the music, you get excited knowing that you will be experiencing something new that day with fresh ears. The highlight of the concert was Lucas Debargue’s performance, although the other two pieces were wonderfully done. He made the piano sing throughout the concert hall and he really knew how to perform alongside the orchestra. After he played the piano concerto, the audience gave him a long ovation and he returned for three more encores. When he played his encores, the audience was quiet and so attentive to make sure they would not miss a thing. It was one of the best solo performances I have ever seen live.

After that concert, I knew that this was only the beginning of my musical experience here in St. Petersburg. Not only will I be attending more orchestral concerts, but I will also be seeing opera productions, ballets, and other small chamber ensembles. This concert reminded me why the history of St. Petersburg musical life will always hold a special place in my heart.

Watching The Nutcracker at the Mariinsky Theater in Vladivostok

By Jonathan Rainey (2016)

Nepotism surely was the only reason the Nutcracker ever landed his job leading soldiers into battle. He’s really not officer material and apparently a band of mostly weaponless rats pose a threat to his army equipped with firearms and artillery. It’s really quite embarrassing.

So I went to see “Щелкунчик” (The Nutcracker) at Vladivostok’s premier Mariinsky Theater of Opera and Ballet this weekend. One of Tchaikovsky’s most popular and enduring ballets, I have seen it numerous times in the United States around Christmastime, but the chance to see it in Russia seemed something special.

The Mariinsky Theater in Vladivostok is under the same management as the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, recognized as one of the world’s premier ballet companies. So, you should have no doubt as to the quality to expect.

Despite my personal misgivings about the titular hero, the dance choreography and set design was of the highest quality. The dancers hail primarily not from the Russian Far East, but from Moscow, Japan, and even as far as Brazil. And while these were first-class, Tchaikovsky’s score, played live by the orchestra stole the spotlight. Every piece was beautifully performed, and the acoustics of the theater emphasized each note to perfection.

The theater itself is among the newer additions to Vladivostok, being built at the same time as the two iconic cable stayed suspension bridges and the massive Far Eastern Federal University in time for the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in 2012. The interior of the theater is very modern and certainly one of the most beautiful buildings in the city. The front of the building is entirely covered by plates of windows, looking out across the brightly lit Golden Horn Bay.

Tickets for the Mariinsky Theater can be purchased online or at one of several locations around the city. The most straightforward method is to purchase tickets at the theater itself. The box office is open every day from 10 am to 7 pm. The schedule of events is available there as well, or at the theater’s website. At the time of writing, the events calendar on the website is only updated on the Russian version of the site.

My ticket for the Nutcracker was very reasonably priced at just 1,000 Rubles (approx. $15). Prices vary by what seat you want, but I had a nice seat in the center, just underneath the balconies and had no trouble seeing the performance. It is usually recommended to buy tickets at least a week in advance to ensure good seat selection.

To summarize, I would classify the Mariinsky Theater in Vladivostok as a must visit in the city. Indeed, I am disappointed that I did not visit sooner. It is a top-notch building, and the performance that I witnessed was to match. I will almost certainly be trying to fit in another performance before the semester finishes next month.

You Might Also Like

(includes current article)

A Musicologist Recommends Three Russian Operas for You to Watch at the Mariinsky

I was so excited about studying abroad in St. Petersburg because I got the chance to see a lot of Russian operas that are not performed in theaters in the West. As a Russian musicologist, it was wonderful to have excess to the musical performances at the Mariinsky Theaters. Opera is one of the most […]