Most foreigners in Warsaw tend to the stick to the center of the city and Old Town, with some maybe venturing as far as the Praga district. Being that these areas are mostly discovered and easy to tour — along with being packed with tourists and locals — I decided to start taking trams to the more distant districts of Warsaw, places where most apartment buildings are architectural leftovers from the Soviet era and which have been slower to evolve with the modern age. One such district — and my favourite of all so far — is the Targówek District, a bit further past the better-known Praga.

I initially went into this area to go hiking in the Bródno Forest (Bródnowski Las), in that district. After a peaceful and invigorating hike, I decided to check out surrounding area, and found three amazing sites: Bródno Sculpture Park, Bródno Cemetery (Polish: Cmentarz Bródnowski), and the Bródno Jewish Cemetery (Cmentarz Żydowski Bródnowskiego).

Nowhere else in Warsaw have I encountered such an acute sense of the historical directly adjacent to the contemporary.

Bródno Sculpture Park is a free, quiet, and open 24/7. It was started in 2009 by Paweł Althamer, an internationally recognized Polish sculptor who was inspired to put Polish artist Grzegorz Kowalski’s concept of “Common Space — Individual Space” into practice. This concept seeks to neutralize individualism in the interaction/communication of artists and viewers.

There are a total of eleven sculptures by various artists scattered around the park. It is a project of social, participative character, with roots in abstract and minimalist art. Althamer has two contributions: “The Garden of Eden” and “Sylwia,” both of which were, in fact community creations. “Sylwia” was created in partnership with artist Grupa Nowolipie and community members with multiple sclerosis who used the art as a form of therapy and rehabilitation. “The Garden of Eden” was also a collaborative effort with community members of the local area, including elementary school students. This sculpture garden thus represents the formation of community around objects that provide an opportunity for gathering, meeting, and taking action together.

One artist, Honorata Martin, lived in the park for weeks in 2015, residing in a tent as a way to perform the idea of inhabiting a city park. Because her piece was inherently ephemeral, only traces of the performance are left. There is a bas-relief called “God the Monkey,” installed where her tent was set up (in Paweł Althamer’s “Garden of Eden”) and poems painted on the pavement by Andrzej Przybysz, a local poet who participated in her performance in the park.

Some of the works are not even visible, as with Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s piece, “To Be Found”: Weiwei buried three cylinders filled with broken pottery, earth, and turf, serving as a conceptual art piece that explores the boundaries of the visible and the invisible, the accessible and the inaccessible. This piece really challenged me, as it forced me to accept that not all things “public” are necessarily accessible.

When considering these three sites — Bródno Sculpture Park, Bródno Cemetery, and Bródno Jewish Cemetery — as part of a whole Bródno, an intense amalgamation of suffering, survival, creativity and joy come to the forefront. Long walks in this area have helped stimulate my creativity and deepen my understanding historical and contemporary Poland, as well as my understanding of Polish cultural weaknesses and strengths in the past and present.

You’ll Also Love

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

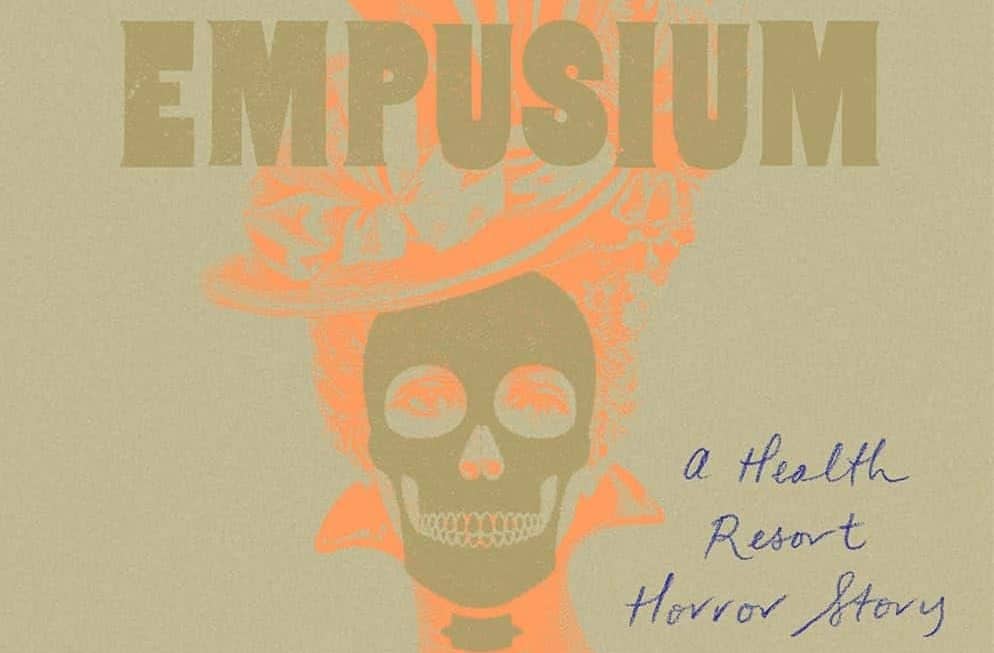

Book Review of The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story

The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story by Olga Tokarczuk, translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones is an expertly woven folk horror story that grapples with the explosion of philosophies that overtook Europe at the turn of the last century as well as questions of gender and the ways in which we interpret the world […]

Chopin Museum and Rememberance, Warsaw

In Warsaw, large, elegant, and beautiful willow trees grace many of the parks within the city. These are the same willow trees that inspired many of the outstanding musical pieces of prodigy composer and native Pole, Frédéric Chopin. Signs of Chopin’s legacy, like the willows that inspired him, can also be seen across the city. […]

History and Art in Warsaw’s Bródno District

Most foreigners in Warsaw tend to the stick to the center of the city and Old Town, with some maybe venturing as far as the Praga district. Being that these areas are mostly discovered and easy to tour — along with being packed with tourists and locals — I decided to start taking trams to […]

The POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

The POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, located in Warsaw, Poland, is a renowned cultural institution dedicated to preserving and presenting the 1,000-year history of Jewish presence in Poland and to promote tolerance, understanding, and mutual respect. It serves as a space for learning, reflection, and dialogue, exploring the rich cultural and religious […]