The Leningrad School was a prominent school of painting during the majority of the Soviet period, 1930-1990. Emanating from the Ilia Repin Institute for Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (named for the famous nineteenth century realist painter and renamed the St. Petersburg Institute for Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture after the collapse of the USSR), it produced a cadre of painters over its long life that sought to establish a continuity with the techniques and styles of earlier forms of Russian realist painting. Although at the forefront of the development of socialist realism, its artists eventually appropriated other artistic styles—chiefly impressionism, though certainly not limited to it—and tackled many subjects outside of the heroic and moralistic social themes of official Soviet art.

Formation of the Leningrad School of Art

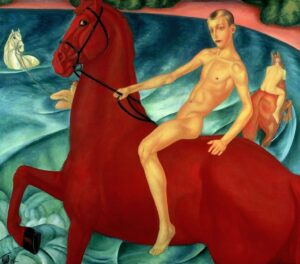

In 1932 there occurred a reorganization of all artistic activity in the Soviet Union. By Politburo decree all previously existing independent arts organizations and unions were dissolved and new unified bodies through which all artistic activity would be coordinated were created in their stead. Accordingly, a Leningrad Union of Artists was established and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin—an influential and innovative painter—was elected as its first president.

The decision to disband prior artistic associations was ostensibly reached on both artistic and education grounds. Artistically, the years following the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 saw an explosion of artistic innovation, wherein many artists adapted the revolutionary dream of human liberation to art—creating new abstract forms, combining media, and pushing the boundaries of visual representation. However, along with these innovations came hostility against the preservation of more traditional forms of painting, which were labeled as bourgeois and reactionary. As a consequence of the constant battle over funding, educational institutions suffered and the quality of instruction declined. Thus, the Politburo decree came to silence many on the radical left who sought a complete break with the past and instead saw a turn towards art that had an elevating social function and that glorified the Communist party and the ideal of Socialist construction. Gone were the geometric abstractions of artists like Kazimir Malevich, whose innovative work became maligned as bourgeois excess.

Out of this milieu emerged the Leningrad School, which sought to establish a connection with the nineteenth century Russian realist painters, and in particular The Wanderers, who had sought to depict the everyday realities of the common people of Russia through highly narrative painting. To this end, the connection to these forbears of Russian nationalist painting was formalized in 1944 with the adoption of Repin’s name to the institute. Additionally, many of the initial instructors at the school were former students of nineteenth century luminaries, among them, Ilia Repin, Pavel Chistiakov, and Arkhip Kiundzhi.

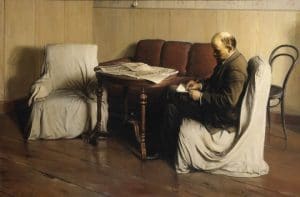

The second director of the school, Isaak Brodskii was also a former student of Repin and the continuity of his paintings with the previous generation is evident in the skill of his naturalistic compositions. His 1930 work, Lenin in Smolny, in many ways can be seen as a template for what would become the standard of socialist realist art. It depicts Lenin in a highly austere setting—completely absent of material luxuries or distractions—with blank walls and only a few pieces of furniture for company. Yet despite the paucity of his surroundings we find him deeply focused on his writing; and the newspapers cluttered on an adjoining table remind us that his concerns are political and social in nature, and that thus, his writing is addressed to the concerns of society. The formal requirements of socialist realist art that would later be canonized are all present in the work, providing the audience with an image highly realistic in its rendering, devoted to a positive representation of the party and its goals, and in a setting whose lack of ostentation brings Lenin down to earth.

WWI and the Leningrad School of Art

Sadly, the output of the Leningrad school was temporarily halted with the outbreak of war on the eastern front in 1941. Many of the school’s instructors and students would find themselves occupied with the war effort in varying degrees rather than with their artistic work for the remainder of the war. Many artists also lost their lives during the Siege of Leningrad, which lasted from 1941 to 1944.

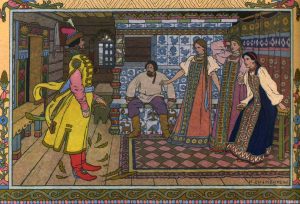

One such loss was the painter, illustrator, including Ivan Bilibin who died early on in the siege but had played a significant role in the revival of traditional Russian art and had a profound influence on the development of the Russian art scene in the early 20th century. Bilibin’s artistic style was characterized by bold lines, vibrant colors, and intricate patterns. He drew inspiration from Russian folklore, epic tales, Slavic mythology and traditional Russian art forms such as lubok (popular prints) and icon painting. Bilibin was involved in teaching and educational activities. He worked as a professor at the Higher School of Art and Technology in St. Petersburg, where he inspired and mentored a generation of young artists.

Despite the official requirements of Soviet art, the Leningrad School’s commitment towards preserving and passing on the skills of traditional easel painting resulted in the production of paintings intended merely to strengthen the skills of the artist; thus many works emerged absent of ideological content in the forms of landscapes, still-lifes, and portraiture.

An excellent example of this can be seen in Anatoli Nenartovich’s 1949 piece, Winter Ship Camp on the Neva River. Nenartovich was a Soviet painter and graphic artist known for his contributions to the genre of landscape painting. Like The Wanderers before him, he focused on capturing the beauty and vastness of the Soviet countryside. He often depicted scenes of rural life, showcasing agricultural activities, villages, and natural landscapes. His paintings displayed a distinct poetic and lyrical quality, with an emphasis on color harmonies and atmospheric effects. His artistic style evolved over time, reflecting influences from different periods and movements. Initially, his works demonstrated elements of traditional academic realism. However, he later incorporated elements of impressionism and post-impressionism into his art, exploring more expressive and experimental techniques. Winter Ship Camp on the Neva River is not only representative of these non-ideological productions but is also indicative of the turn towards the more impressionistic trends that would come to occupy the Leningrad school from the 1950s onwards.

Khrushchev’s Thaw and Greater Artistic Freedom

The first generation that emerged from the auspices of the Institute’s return to realism began to further stretch the boundaries of official Soviet art. Along with Khrushchev’s Thaw, which condemned the excessive repressions of the Stalinist era, came a more relaxed attitude towards the products of the Soviet art world. Accordingly, artists such as Arsenii Semionov, Nikolai Baskakov, Sergei Osipov, Lev Russov, and many others, began to explore different themes and explore differing painterly techniques. The era from the late 1950s throughout the 1970s saw an explosion of artistic work depicting landscapes, city scenes, village life, portraiture, and still lifes—all of which avoided the common socialist realist themes of utopian construction or party-elevating compositions.

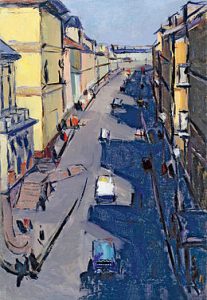

Semionov’s 1959 piece, Spring Day in Leningrad, is exemplary of the turn during this era. It sparsely renders a procession of vehicles down a wide city street in rough almost child-like sketches of color. Lost are the precise attention to detail found in the canon of socialist realist art, and instead we are graced with merely the outlines of objects—quickly brushed out lines of buildings with their shadows stretching across the street and the splotches of indistinct pedestrians like ghosts on the pavement.

Moreover, although this output remained realistic at its core—in that it always unambiguously portrayed actual objects and never strayed into the realm of pure abstraction—artists nonetheless began to utilize the more dreamy techniques of impressionism and post-impressionism in the construction of their work. These pieces also, on occasion, avoided the positivist portrayals of socialist realism, presenting much more somber representations of Soviet realities.

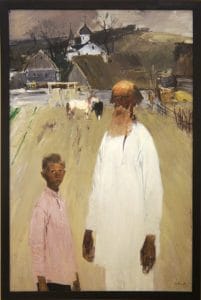

Yevsei Moiseyenko, who was born in the Dmytrivka, in what is now Ukraine, and who studied at the Odessa Art School and later at the Kharkiv Art Institute, eventually moved to Leningrad where he painted some excellent examples of darker Soviet art. Moiseyenko’s artistic style primarily focused on landscape painting, particularly scenes depicting the Ukrainian countryside. His works displayed a distinct realism, with attention to detail and an emphasis on capturing the light and atmosphere of the depicted scenes.

Moiseyenko’s 1963-64 piece, Sergei Yesenin and his Grandfather, illustrates a young boy and an old man, both with troubled expressions on filthy faces, situated on a small strip of farmland dominated by a church in the distance and a dour, stormy sky. The image could not be more contrasted with the heroic portrayals of socialist realism.

The general trend towards more personal and affective pieces that exemplified everyday life and celebrated both the natural landscapes of the USSR and its architecture, people, and customs, would continue for the remainder of the Leningrad School’s life. Moreover, the 1970s saw a new generation of artists maturing through the institution and carrying on further experimentation with impressionistic compositions and ever varying uses of light and color. Some artists even went beyond established conventions and tore asunder the boundaries of acceptable themes and approaches.

The Leningrad School and The Arrival of Perestroika

As the political climate in the USSR began to ease and breakdown in the 1980s, this experimentation reached perhaps its greatest height.

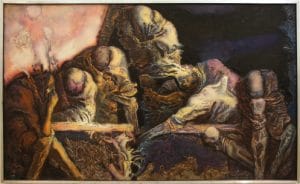

This can be seen well in the work of Vyacheslav Mikhailov, who studied under Yevsei Moiseyenko at the Repin Institute. Alongside Valery Lukka and Felix Volosenkov, he co-founded The Three Bogatyrs art group, exploring new techniques using levkas, a technique from icon painting. A levka uses a mixture typically made from a combination of chalk or gypsum, animal glue (usually rabbit-skin glue), and water to create textured surfaces that allow the painter to accentuate light and color.

Yet even Vyacheslav Mikhailov’s grotesque 1984 piece, The Last Supper—although highly discontinuous with the general output of the school—demonstrates the continued commitment to technical mastery and the ever-increasing desire for innovation. He values memory, balancing present and past in his art.

The Legacy of the Leningrad School of Art

Despite the fact that the products of the Leningrad School were highly celebrated in the Soviet Union— especially following a 1976 exhibition in Moscow that affirmed within Soviet society the unique contribution of the Leningrad School to the development of Soviet art—much of the rest of the world remained either ignorant of, or uninterested in, its output. Although the school’s work was shunned in some circles as reactionary in a world of abstract and post-modern art, the posthumous fate of the Leningrad School has been much more accepting. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the concomitant collapse of the institute, an expanded interest has evolved in the works of these twentieth century Russian masters, whose willful connection with the painterly techniques of their forebears and their bucking of Western artistic trends, maintained the traditions of Western painting in perhaps the most unlikely of places.