The name Magtymguly Pyragy might sound hopelessly unfamiliar to a Western ear. For Turkmens, the main ethnic group inhabiting the former Soviet republic Turkmenistan, however, it is a household name.

Magtymguly (pronounced Mahg-tim-goo-lee) was an 18th century Sufi poet and spiritual teacher. Today he is considered the father of Turkmen literature and is a nationally celebrated cultural icon. His renown largely persists through a rich, ingrained tradition among Turkmen bards or bagshy of adapting his poetry into song. A continual source of sustenance and pride for his people, Magtymguly’s image and biography have also played a constitutive role in Turkmen modern history, providing a poetic vision for a unified Turkmenistan.

Magtymguly’s Nation and Legacy

Turkmenistan is a remote Central Asian country, home to just over 6 million, who speak a language closely related to Turkish. Approximately the size of California, the Turkmen landscape is mostly desert, bordered on the west by the Caspian Sea and traversed in the east by the historic Amu Darya River.

It is believed that the Turkmen people derive from the Oghuz branch of the Tartaric diaspora, who began populating Central Asia around the seventh century, having occupied most of what is now Turkmenistan by the twelfth century. Today, small populations of Turkmens also inhabit parts of Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey.

Early adopters of Sunni Islam, the Turkmen people were included in surveys of the Islamic world as early as the 10th century, though in Turkmenistan a syncretic blend of pre-Islamic and Sufi customs has been practiced alongside more traditional worship.

The ancient city of Merv, the ruins of which are now a world heritage site in Eastern Turkmenistan, was once the capital of the famed Seljuk Empire. At the height of its development in the twelfth century, the city had become so commercially and culturally significant that Persian geographers referred to Merv as the “Mother of the World”. Merv’s preeminence quickly came to an end in 1221, when the Mongols demolished the city and nearly wiped out its population.

Magtymguly lived in the 18th century, which witnessed successive political upheavals across Central Asia. A radical regime change in Persia and the emergence of Afghanistan as a modern nation had a deep impact on regional political stability. Factions among the Turkmen tribes, then under Persian rule, took advantage of these developments by lobbying for an independent Turkmen state. Though Magtymguly was not the only poet of his generation to call for Turkmen unification, he was the first known to develop this as a central motif in his poetry.

Magtymguly’s dream for a united Turkmenistan was never realized in his lifetime. When the Russian Empire conquered the region in 1881, it was home to a disarray of distinct tribes, some in alliance with one another, others in rancorous conflict. Russian authorities began in earnest to convert the territory into an industrial producer of cotton and fuel, expedited in 1889 by the completion of the Transcaspian Railway. Despite efforts toward unification, the territory was still volatile and steeped in factionalism when, in 1925, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic was founded as an autonomous state within the USSR.

Magtymguly’s legacy runs like a continuous thread throughout the developments of 20th century Turkmen socialism. Soviet officials adopted a widespread policy in Central Asia of fostering localized cultural narratives, hoping that these might be vehicles for official Soviet pedagogy.

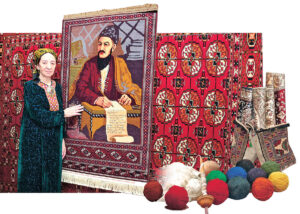

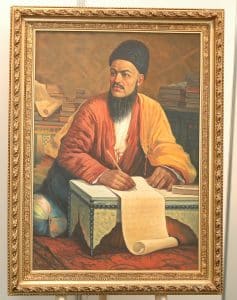

In Soviet Turkmenistan, appreciation of Magtymguly’s poetry continued to expand across media, influencing such canonic works as Aihan Hajiev’s Portrait of Magtymguly (1947), in which the poet is depicted in a moment of inspiration, seated on a carpet with Teke insignia. The painting sets Magtymguly squarely in dialogue with Turkmen national heritage, since the Teke were celebrated as the last major tribe to fall under Russian conquest.

In the other arts, Veli Mukhatov’s first symphony To the Memory of Magtymguly (1976) is considered by many to be the pinnacle of Turkmen symphonic composition. Over the course of six sections, this well-known masterpiece ranges from quiet gravitas to capricious passion, evoking the spectrum of Magtymguly’s patriotic and spiritual connection to his homeland.

Throughout the 20th century, a new European artistic style was adopted by Turkmen visual artists. Also during this time, Turkmenistan’s rich history in textiles was transformed into a fine art, and many tapestries called gobelins were devoted to Magtymguly’s life and teachings. Vera Gylliyeva’s 1982-1985 gobelin, titled Constellation portrays Magtymguly along with six other sages standing under the tree of knowledge. This quote from Magtymguly’s famous poem Türkmeniň (The Land of the Turkmen) is emblazoned over the poet’s head:

When souls, hearts and minds of tribes are united…

When Turkmen gather around one table to share a meal. (Taylor 2014: 15)

Who is Magtymguly?

The specific dates of Magtymguly’s birth and death are debated. Most accounts attest to his having been born no earlier than 1724 and having died no later than 1807. It is generally agreed that he was born in a village called Haji-Qushan in the Golestan region of present-day Iran. Magtymguly identifies himself as a member of the Gerken branch of the Göklen tribe, a prominent tribe along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea.

Magtymguly’s father, Döwletmämmet Azady, was the first literary writer in recorded history to use the Turkmen language, and was also a respected mullah, a religious scholar in the Muslim tradition. Both Magtymguly and his father were among the first Turkmen writers to be educated within a madrasa – the highest form of education in 18th century Central Asia.

Magtymguly attended two madrassas, first in Eastern Turkmenistan and then Bukhara, before completing his studies at Şirgazy Madrassa in Khiva, where his father also attended (Bukhara and Khiva were major cosmopolitan centers at the time, now regions of Uzbekistan). Having completed his studies, Magtymguly returned home and worked for a period as a teacher and metalsmith.

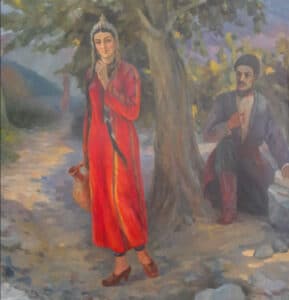

Many of Magtymguly’s poems are dedicated to a woman named Mengli, with whom he was desperately in love. She was given in marriage to another, a constant source of heartbreak for Magtymguly. He ultimately married another woman named Ak-kyz, who gave birth to two sons, both of whom died young.

Magtymguly was no stranger to loss. Additionally, Magtymguly’s sister appears to have died when the poet was 21, and his two brothers who worked as ambassadors for Ahmad Shah Durrani (a statesman today regarded as the founder of modern Afghanistan), seem to have disappeared while on a diplomatic mission. These events, compounded with the death of Magtumguly’s father when the poet was still a young man, had a demonstrable effect on Magtymguly’s verse, which often gravitates around themes of loss and acceptance.

Magtymguly Pyragy’s pseudonym – “Faraghi” in Persian – derives from an Arabic word meaning “separated one”, not unfitting for a Sufi poet, though particularly meaningful for Magtymguly’s biography.

Not only did Magtymguly’s life experiences figure extensively in his verse, his widespread travels across the Near East provided him with an intimate knowledge of the history, culture, and geography of his region. While studying in Bukhara, he and respected Syrian scholar Nuri Qasim Ibn Bahr made excursions as far as Northern India. After this period, Magtymguly often travelled across the Turkmen territory as an itinerant teacher and spiritual guide, and late in life visited Baku, Azerbaijan. Some accounts posit that Magtymguly may have been taken prisoner in Mashad, Iran, though details of this event are ill-defined.

Despite his sundry adventures across Central Asia, Magtymguly’s burial site in Golestan, Iran is less than 100 miles from his birthplace. Every year, thousands of Turkmen from all over the Near East undertake a pilgrimage to his grave to pay their respects.

Magtymguly’s Poetry

Magtymguly’s corpus is no less ambiguous than his biography. Of his approximately 800 extant poems, the vast majority derives from late 19th century printings, while most of his spiritual poems source from the 20th century. These publications are the result of an extensive transcription campaign after the majority of Magtymguly’s poetry had existed for generations in oral form, or as song lyrics.

Because poetry written in Arabic script was systematically destroyed by Soviet authorities, it is possible that some older manuscripts were safeguarded and have yet to surface. Nonetheless, without a comprehensive archive or accurate indexing system, distinguishing authentic Magtymguly poems from those written later by imitators can prove extremely difficult.

Despite concerns over origin, the work attributed to Magtymguly has had a deep impact on modern Turkmen literature and culture, due to its literary prowess, versatility, political activism, and the author’s recurrent plea for Turkmen national unity and spiritual awakening.

Magtymguly’s career as a poet coincides with an epochal shift in the development of the Turkmen language. Beginning in the 18th century, a Turkmen literary language is introduced, largely due to the influence of Magtymguly, his father, Azady, and contemporary, Andalib.

Turkmen poetry of the time was an eclectic mix, but a frequent poetic form for Magtymguly and his contemporaries was the gazhal, a type of ode originating in Arabic poetry around the 7th century, and popular among medieval Persian poets. Whereas Andalib’s Turkmen gazhals are clearly adherent to formal tradition, Magtymguly’s gazhals, much like the rest of his poetry, are idiosyncratic, unpredictable, and often internally diverse. In one poem, for example, Magtymguly can blend the form’s traditional pining over lost love with philosophical reflections, Sufi imagery, autobiographic details, and/or patriotism.

In addition to the ghazal, Magtymguly favored the qoshuk, a lyric form that features regularly in Turkmen folk songs. Magtymguly’s fondness for the qoshuk undoubtedly contributed to his legendary status among Turkmen bards, known as “bagshy.” Specialists among the bagshy community devote themselves to the memorization of hundreds of Magtymguly’s poems set to traditional musical accompaniment. It is thought that Magtymguly may have sung his own poetry, due to numerous references to song throughout his poetry.

Replete with metaphors of shared feasts and military valor, Magtymguly’s poems are often explicitly nationalistic, calling for unity among the various Turkmen tribes and developing a common Turkmen heritage, distinct from Persian or Tartaric culture. Much of Magtymguly’s poetry also strives to expose the cruelty of historical or regional leaders and hypocrisy of false religious figures, while promoting attentive, humble worship and avoidance of vice.

Finally, Magtymguly’s thematic development is vast and ranges from an epic historical register to personal lament. Moreover, Magtymguly is widely known among his countrymen as the pioneer of Turkmen literary realism. Ethnomusicologist Walter Feldman highlights the simplicity with which Magtymguly often writes, also noting features of secularism and rationalism in his poetry, uncommon for traditional Sufi verse.

One well-known poem is “The Land of the Turkmen,” presented below in the original and in an English translation by Paul Michael Taylor, who has many other English translations online.

| TÜRKMENIŇ | The Land of the Turkmen |

| Jeýhun bilen bahry-Hazar arasy,

Çöl üstünden öser ýeli türkmeniň; Gül-gunçasy – gara gözüm garasy, Gara dagdan iner sili türkmeniň. |

Between the Jeyhun river and the Hazar sea,

The wind of the Turkmen land rises above its deserts, Its blossoming flowers are as precious as the apples of my black eyes, Torrents rush from the slopes of its tall black mountains. |

| Hak sylamyş bardyr onuň saýasy,

Çyrpynşar çölünde neri, maýasy, Reňbe-reň gül açar ýaşyl ýaýlasy, Gark bolmuş reýhana çöli türkmeniň. |

The Almighty blessed this land with His care,

The herds of thoroughbred camels graze in its deserts, Its green meadows will blossom with colorful flowers, The Turkmen steppes are filled with sweet basil. |

| Al-ýaşyl bürenip çykar perisi,

Kükeýip bark urar anbaryň ysy, Beg, töre, aksakal ýurduň eýesi, Küren tutar gözel ili türkmeniň. |

Its fairies will appear in their colorful dresses,

The sweet smell of ambergris will fill the air all around, The beg, töre and elderly are owners of the country, The beautiful land of the Turkmen will be filled with populated and prosperous villages. |

| Ol merdiň ogludyr, mertdir pederi,

Görogly gardaşy, serhoşdyr seri, Dagda, düzde kowsa, saýýatlar diri Ala bilmez, ýolbars ogly türkmeniň. |

He is a son of a brave man, his forefathers were brave,

Görogly is his brother, his enthusiasm is high, If hunters hunt for him in the mountains or steppes, A Turkmen, the son of a lion, won’t be caught alive. |

| Köňüller, ýürekler bir bolup başlar,

Tartsa ýygyn, erär topraklar-daşlar, Bir suprada taýýar kylynsa aşlar, Göteriler ol ykbaly türkmeniň. |

When souls, hearts and minds of tribes are united,

Their troops when gathered will melt stones and ground on their way, When Turkmen gather around one table to share a meal, The destiny of Turkmen will rise high. |

| Köňül howalanar ata çykanda,

Daglar lagla döner gyýa bakanda, Bal getirer, joşup derýa akanda, Bent tutdurmaz, gelse sili türkmeniň. |

The spirits get high when on a horseback,

Its mountains, at a glance, look like rubies, When its rivers are full-flowing, bringing honey within, No dam can withstand the floods of the Turkmen land. |

| Gapyl galmaz, döwüş güni har olmaz,

Gargyşa, nazara giriftar olmaz, Bilbilden aýrylyp, solup, saralmaz, Daýym anbar saçar güli türkmeniň. |

They will not be taken unaware by intruders, nor trampled down in battle;

They are not dependent on either a curse or violence, They will neither wither nor yearn when separated from a nightingale, The flowers of the Turkmen will always spread the fragrance of the ambergris. |

| Tireler gardaşdyr, urug ýarydyr,

Ykballar ters gelmez hakyň nurudyr, Mertler ata çyksa, söweş sarydyr, Ýow üstüne ýörär ýoly türkmeniň. |

All tribes are in brotherhood, all clans are at peace,

Their destinies won’t go counter; they are the Creator’s blessing, If the brave straddle their horses, the battle will be over, The only path Turkmen take is toward the intruders. |

| Serhoş bolup çykar, jiger daglanmaz,

Daşlary syndyrar, ýoly baglanmaz, Gözüm gaýra düşmez köňül eglenmez, Magtymguly – sözlär tili türkmeniň. |

They will have their spirits high and be cool inside,

They will crumble stones; nothing can stop them on their way, I won’t cast a glance anywhere else; my soul will not take joy, Magtymguly, the elderly of Turkmen will have his say. |

Magtymguly and Turkmenistan in the 21st Century

The poetry and legacy of Magtymguly are deeply interwoven into the culture and everyday existence of contemporary Turkmenistan, in the nearby regions of Uzbekistan and Karakalpakistan, and among Turkmen populations in Russia, Iran, and elsewhere.

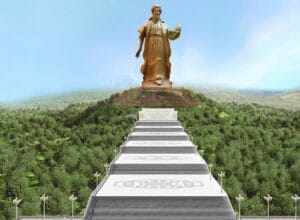

Magtymguly’s verses are regularly heard during Turkmen weddings and cultural festivals, traditionally sung by bagshys. Additionally, visitors to Turkmenistan’s modern capitol of Ashgabat encounter numerous landmarks bearing tribute to the poet, including the Magtymguly National Music and Drama Theater, Magtymguly State University, and Magtymguly Avenue, one of the city’s major thoroughfares. Several monuments and plaques, such as a large statue of the poet in Ashgabat’s Independence Square, testify to the omnipresent appreciation of the poet. Since 2012, Magtymguly’s portrait has even graced the front of the 10 manat banknote.

Social organizations and awards bear the name of the poet, such as the national Magtymguly Youth Organization, an educational program for rural youth, founded in 1991. Since 1992, The Magtymguly International Prize has been awarded annually to distinguished scholars in the field of Turkmen language and literature.

Furthermore, Magtymguly has become a symbol of Turkmen national identity and international pride. The International Organization of Turkic Culture recently declared 2014, the 290th-year anniversary of the poet’s birth, the “Year of Magtymguly.” This designation precipitated numerous events in Turkmenistan and abroad commemorating the poet’s work, including two international conferences, a handful of new Turkmen poetry editions, and a massive translation campaign into 22 world languages, including English. In his New Year’s address of 2015, Turkmen president Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow claimed that the “Year of Magtymguly” reinforced Turkmen pride in their national, cultural, and spiritual inheritance.

In 2024, to mark the 300-year anniversary of Magtymguly’s birth, the Turkmen government in collaboration with global partners, will host an international conference and city-wide events in Ashgabat. This will include the unveiling of a comprehensive digital database and new print collections of Magtymguly’s work and biography. In advance of the anniversary, Turkmen officials are erecting a 197-foot bronze statue of Magtymguly at the center of a 33 acre complex in the southern district of the city. The ribbon-cutting for the complex is slated for later this year, to coincide with June 27, the national holiday honoring the poet.

Though virtually unknown in the West, Magtymguly’s life and work has achieved iconic status for Turkmens, and the poet’s reputation has played a significant role in the nationalism at the center of the country’s post-Soviet authoritarian regime. Economically, Turkmenistan has been able to secure a place in the 21st century globalized world mainly as a natural gas supplier to Russia and China – the country is currently sixth largest producer of natural gas in the world. Nonetheless, despite the World Bank’s ranking of Turkmenistan as an upper-middle income country, most of its population lives below the poverty line, due in large part to its state-monopolized economy. A discernible political opposition is currently in exile, advocating political reform back home.

As Turkmenistan remains a strong regional player and gains more global visibility, Magtymguly’s dream of a peaceful, unified, prosperous, and wise nation should be remembered as a core component of Turkmen heritage, one that offers a continuous through-line for a culture whose national history is anything but continuous.

You Might Also Like

Museums as Self-Care

In 2018, doctors in Montreal began prescribing visits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) for patients experiencing depression, anxiety, and other health issues. This innovative approach to mental health treatment was launched under the initiative of the MMFA in collaboration with Médecins francophones du Canada (MFdC). The program allows physicians to provide patients […]

Guide to Bishkek’s Top Museums for Students

The Kyrgyz were largely a nomadic civilization up until the 20th century. The city of Bishkek has a number of museums documenting this fascinating history as well as the development of the arts and sciences in Kyrgyzstan. These museums were mostly established during (and today are often unchanged from) Soviet times, including a number of […]

The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan

The State Museum of Applied Art and Handicrafts History of Uzbekistan provides an excellent introduction to Uzbek history and culture. Centrally located in Tashkent, it displays more than 7,000 examples of traditional folk art. These include a range of mediums from decorative glass to porcelain and fabrics, all dating from the first half of the […]

Nukus Museum in Uzbekistan: Lysenko, Savitsky, and Preserving the Soviet Avant-Garde

In the remote Nukus Museum of Uzbekistan, a vast collection of banned Russian avant-garde art has been preserved for decades. The museum and its collection were founded by Igor Savitsky, a Soviet artist who defied censors to rescue and safeguard these works. His success was also made possible by the unique geography and history of […]

The Amir Timur Museum in Tashkent

The Amir Timur Museum, also known as The State Museum of Timurids History, stands proud at the center of Tashkent. Built in 1996 to mark the 660th anniversary of Amir Timur’s birth, the museum celebrates what it sees as a glorious history and places modern Uzbekistan as the direct descendant of that history. A visit […]